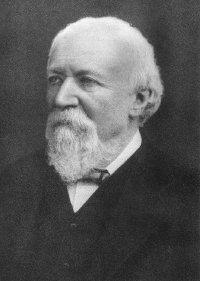

Robert Browning

House

1

Shall I sonnet-sing you about myself?

Do I live in a house you

would like to see?

Is it scant of gear, has it store of pelf?

“Unlock my heart with a

sonnet-key?”

2

Invite the world, as my betters have done?

“Take notice: this building

remains on view,

Its suites of reception every one,

Its private apartment and

bedroom too;

3

“For a ticket, apply to the Publisher.”

No: thanking

the public I must decline.

A peep through my window, if folk prefer;

But, please you, no foot

over threshold of mine!

4

I have mixed with a crowd and heard free talk

In a foreign land where

an earthquake chanced;

And a house stood gaping, naught to balk

Man’s eye wherever he gazed

or glanced.

5

The whole of the frontage shaven sheer,

The inside gaped: exposed

to day,

Right and wrong and common and queer,

Bare, as the palm of your

hand, it lay.

6

The owner? Oh, he had been crushed, no doubt!

“Odd tables and chairs

for a man of wealth!

What a parcel of musty old books about!

He smoked—no wonder he

lost his health!

7

“I doubt he bathed before he dressed.

A brazier?—the pagan, he

burned perfumes!

You see it is proved, what the neighbours

guessed:

His wife and himself had

separate rooms.”

8

Friends, the goodman of the house at least

Kept house to himself till

an earthquake came:

‘Tis the fall of its frontage permits you

feast

On the inside arrangement

you praise or blame.

9

Outside should suffice for evidence:

And whoso desires to penetrate

Deeper, must dive by the spirit sense—

No optics like yours, at

any rate!

10

“Hoity toity! A street to explore,

Your house is the exception!

‘With this same key

Shakespeare unlocked his heart,’ once more”

Did Shakespeare?

If so, the less Shakespeare he!

I could find no text of this poem

on the web, so I decided to post it myself.

I hope those of you who come to this page enjoy

this late poem ( 1876) of Robert Browning. I find it remarkable.

Unlike much of his poetry, which was written in the dramatic monologues

he helped create, this poem comes rather directly from its author.

Ironically, its subject is a defense of not being direct: of charting a

different course from those who write about their innermost feelings, as

Romantic and more recently confessional poets do, and thus expose their

inner life to the reader.

Here’s what I like about the poem:

· It has a wonderful verve that we associate with much

of Browning, and is filled with questions, exclamations, stupidities (the

vapid comments of the passers-by) and that wonderful “Hoity toity” in the

last stanza. And it even ends up criticizing Shakespeare (Browning

is responding to Wordsworth’s line in “Scorn not the Sonnet” where Wordsworth

writes, “With this same key Shakespeare unlocked his heart.”

· Browning is ever the ironist. Even that last line criticizing

Shakespeare is ironic, since the greatest poetry of Shakespeare is his

plays, which present the world dramatically, its exterior actions and characters,

and not in some ‘exposure’ of Shakespeare’s heart. And doubly ironically,

since from their writing until today, no one really can see into what was

in Shakespeare’s heart in the sonnets: we still are not entirely sure what

was inside Shakespeare’s heart when he wrote those poems – or even to whom

he was writing them!

· That great metaphor, of the house wall torn away by earthquake,

and all the folks in the crowd peeping, gaping at the gaping house, and

gossiping about the mess, the paganism and the marriage habits of

the just-dead owner.

· We live with surfaces: “Outside should suffice for evidence”

· We see with our imaginations, not our eyesight: we know what

is within another person by observing clearly and using our minds and hearts

and imagination – just as we do when we ‘listen’ to one of Browning’s monologues.

Browning’s poetic rhythms were justly acclaimed by the

modern poets – Ezra Pound above all. His reticence – his wanting

to avoid the “spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings” that Wordsworth

had called for – became a central guide for modernist poetry in England

and America. He taught them not to rip away the outer walls and let

their inner lives hang there for people to gape at: build a house and let

readers “penetrate deeper…dive by spirit-sense,” he said – and his example

showed them how.

A final word. I think Browning would, for all

his late celebrity, have empathized on very deep levels with his contemporary

Emily Dickinson:

I'm Nobody! Who are you?

Are you—Nobody—Too?

Then there's a pair of us!

Don't tell! they'd advertise—you know!

How dreary—to be—Somebody!

How public—like a Frog—

To tell one's name—the livelong June—

To an admiring Bog!

Also, another Browning text I have posted: Dis

Alter Visum; or The Byron de Nos Jours

To help out a friend and former student, Elliot Earle, I am putting

a web page link to his home page here. You can visit it if

you wish: he makes stone sculptures, and wonderful tables made of stone

and (!) water. Go to:

http://elliotearlesculpture.com/index.html