Utah

Number of Victims

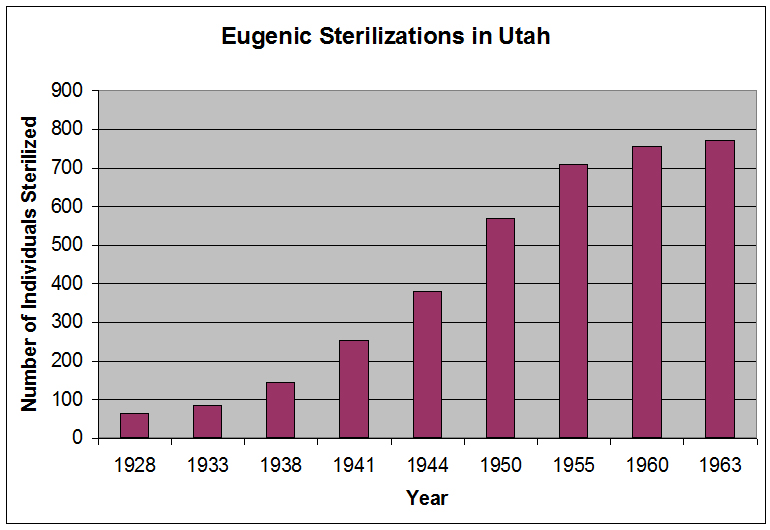

772 individuals were sterilized under the Utah law, of whom 54% were women. Approx. 15% of victims were considered mentally ill and the remaining 85% were considered mentally deficient. Utah ranks 16th highest in the nation for eugenic sterilizations.

Period during which sterilizations occurred

Sterilizations in Utah did not begin until the passage of the 1925 sterilization law (Spreadsheet). The last sterilizations occurred in 1960 (Paul, p. 488).

Temporal pattern of sterilizations and rate of sterilization

The number of sterilizations remained relatively low until the late 1930s. It remained low following the Davis v. Walton case in 1929, with only 6 sterilizations occurring between 1930-35 (Paul, p. 478). The annual rate of sterilization was much higher after the opening of the Utah State Training School in 1935 to the early 1950s, after which period it declined (Paul, p. 488). During the peak period, about 33 persons were sterilized annually. The rate of sterilizations per 100,000 per year was approximately 5 during this time.

Passage of Laws

In Utah, sterilization was recommended as early as 1912 in the biennial report of the State Board of Insanity (Painter). A eugenics bill was passed in 1925 (Ordover, p. 80; Painter). The 1925 law was slightly amended on March 23, 1929, without much affecting the application of the law; it changed the purpose of the board of directors so that they were solely a board for the purpose of conducting the proceedings. Later, on March 25, 1929, the law was again amended to allow the superintendents and the board of trustees at the Utah State Training School the same rights of sterilization as prisons (Landman, pp. 86-87). The law was also amended slightly in its wording and in the procedure required for a sterilization to take place (Paul, pp. 479-481). Utah was 23rd state to pass a compulsory sterilization law.

An Important Case

The 1929 case of Warden Davis v. Esau Walton is famous and involves the proposed sterilization of Esau Walton, a homosexual African American. An inmate of the Utah State Prison, Walton was born in Georgia but left the state following his mother’s death in 1923. He was imprisoned for habitual theft and stealing “silk shirts” (Ordover, p. 80). In the Davis v. Walton case, Walton was accused of participating in an act of sodomy with another inmate (Paul, p. 477) by R. E. Davis, who was the prison warden that had witnessed the act (Ordover, p. 80). Davis eagerly recommended sterilization on the basis of Walton’s race and homosexuality (Ordover, p. 80). For their argument, the defense reviewed most, if not all, state statutes and judicial decisions pertaining to sterilization and raised many legal objections, i.e., sterilization as a cruel and unusual punishment, denying equal protection, and its possible abuse (Landman, p. 88). The Court’s ruling upheld the constitutionality of the forced sterilization, but Walton was not sterilized because there was no evidence that Walton’s condition was hereditary. Due to this, there was no basis for sterilizing; the law states that “Its purposes are eugenics and therapeutic” (Ordover, p. 80).

Groups identified in the law

The original bill targeted “habitual sexual criminals, idiots, epileptics, imbeciles, and the insane” (Landman, p. 87). A 1929 amendment to the bill added “habitual degenerate sexual criminal tendencies.” (Ordover, p. 80; Painter). However, 555 individuals sterilized prior to 1948 were all deemed “insane or mentally retarded” (Painter). An amendment to the law in 1961 added a statement recognizing that an individual could be sterilized if he/she was “probably incurable and unlikely to be able to perform properly the functions of parenthood” (Paul, p. 481).

Process of the law

According to the 1925 law, individuals could be sterilized without consent if the proper legal process was upheld. The sterilization of any individual that was deemed to pose a threat to the hereditary health of the state could be compulsorily sterilized under the jurisdiction of the superintendent of a state institution. Under the process of law, the superintendent must petition the special board of directors and prove that the inmate should be sterilized for eugenic or therapeutic reasons. The inmate in question must be given thirty days for them or their legal representative to prepare a defense, after which the board of directors will conduct a hearing to deliberate the proposed sterilization. After the ruling, the inmate is entitled to an appeal to the circuit court and the supreme court of his state in order to fully protect his rights. Any other method or procedure of human sterilization is deemed a felony (Landman, pp. 86-89). The 1961 amendment to the law required evidence in favor of a sterilization to be recommended by a medical doctor, a psychologist, and a social worker (Paul, p. 479).

Precipitating Factors

At the time of the passing of the eugenics bill, homophobia was widespread in the state. The fear of gay men was widespread because one still had the potential to marry, despite “knowing himself to be affected,” which was said to result in “diseased or defective offspring” (Painter). Castration was proposed as an “alternative to imprisonment for certain crimes of sexual perversion.” The Davis v. Walton case is an illustration of the widespread fear of homosexuals in Utah and the attempt to label and control gays and lesbians (Painter). Although it was continually upheld that acts of sodomy are acquired and not hereditary, there was a large public movement to expand the sterilization bill to include sterilization of “habitual” criminals (Landman, p. 89).

In the 1920s, the presence of a large Mormon

population in Utah may also have affected the adoption of the

sterilization law. As Christine Rosen has argued in Preaching Eugenics,

marriage was encouraged among Mormons, but not for those who had

“infirmities of mind or body” (Rosen, p. 134). Since the body was

considered “housing” for a person’s soul, and the development of the

soul was reliant on the fitness of the body, Rosen views Mormon

doctrine to have not been adverse to its own form of eugenics. It was

considered one’s “duty to see to it that no defective bodies are

provided” (Rosen, p. 135). The fact that Mormon families, including

those of Brigham Young and Joseph Smith, had ostensibly “very few

defectives” in them supported the concept that the Mormon approach to

eugenics was effective (Rosen, p. 134).

In 1913, a eugenicist at the Second Field Worker’s Conference stated

that the family lineage of Brigham Young, the revered founder of

Mormonism, was “an untapped trove of useful hereditary

information” (Rosen, pp. 134, 226). Polygamy, the common

practice of Mormon men marrying multiple wives, proved titillating for

eugenicists who sought to discover if this custom had any effects on

heredity (Rosen, p. 134). However, by 1928 the eugenicist Roswell

Johnson wrote that polygamy in the Church of Latter-Day Saints was “of

little importance” because mainstream Mormonism shunned the tradition

(Rosen, p. 134). Ultimately, Johnson was of the opinion that

Mormons “added to traditional Christianity ‘some theological positions

and some practices of great moment to eugenics’”(Rosen, p. 134).

Stanford University professor Mary Varney Rorty

argues that many Mormon families conceived of themselves as extremely “fit,” and

therefore might have found positive eugenics somewhat appealing. In particular, the

Mormons kept detailed family trees that were important to the

fledgling science of eugenics. These family trees offered a lot

of data about heritable traits passed down from a family’s patriarch to

his offspring. For instance, Rory offers the example of Brigham

Young’s daughters, all eleven of whom were said to have inherited

specific Young-like traits such as “amiab[ility], genuine[ness],

sincere[ty]…genero[sity]”(Rorty). The Church of

Latter-Day Saints' record appear to have been an important source of information for eugenicists.

Groups victimized

Julius Paul notes that Dr. Mark K. Allen, a clinical psychologist at the Utah State Training School, reported that almost all sterilizations performed through the institution were on mental defectives (Paul, p. 478). Indeed, Utah may have been only one of six states with sterilization laws that did not sterilize anyone who was not considered mentally ill or deficient.

Related restrictions

An anti-miscegenation marriage act passed in 1888 restricted and discouraged interracial marriage (Adams).

Major Proponents

Sadie Myers, a volunteer social worker, wrote scathing remarks on poor families on the Utah countryside in 1916, including “frequent cases of goitre” and “incest and illegitimacy running rampant,” resulting in feebleminded offspring (English, p. 158). The State Board of Insanity recommended the 1925 eugenic sterilization bill (Painter).

“Feeder institutions” and institutions where sterilizations were performed

(Photo origin: Utah State Hospital, 1896, available at http://www.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~asylums/utah_ut/index.html)

(Photo origin: Utah State Hospital, 1896, available at http://www.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~asylums/utah_ut/index.html)

Sterilizations took place at the Utah State Hospital, which was also called the Territorial Insane Asylum (“Utah State Hospital”). It is currently an accredited state hospital (http://www.ush.utah.gov/). The Utah State Training School was the residence of nearly 85% of all sterilization victims (Paul, p. 486). It is currently the Utah State Developmental Center (MRAU). Utah State Prison was the site for Walton’s alleged crime for the Davis v. Walton case (Ordover, p. 80). It is still a state prison today (“Utah State Prison”). None of the aforementioned locations includes any mention of their history in regard to the eugenics movement.

(Photo origin: http://content.lib.utah.edu/cdm4/item_viewer.php?CISOROOT=/USHS_Class&CISOPTR=16653)

(Photo origin: http://content.lib.utah.edu/cdm4/item_viewer.php?CISOROOT=/USHS_Class&CISOPTR=16653)

In 1973, Paul Ricks conducted a study entitled “Attitudes of

Administrative and Professional Staff Personnel at the Utah State

Training School Towards Sterilization of the Mentally Retarded.”

This study was conducted in order to explore the practice of

sterilization of the mentally retarded in Utah, and the opinions

expressed in the study were those of staff at the Utah State Training

School (Ricks, p. x). Generally, sterilization was seen as

beneficial for the mentally retarded, because becoming parents was not

in their best interest or the interest of their potential

children. However, many staff members voiced the opinion that

sterilization should never be undertaken lightly, and that “evaluations

from the psychological, social, and medical fields should be part of

any recommendation for sterilization” (Ricks, p. x). Ultimately, the

staff recognized the need for sterilization of the mentally retarded in

Utah (Ricks, p. xi).

Parole Protocol at the Utah State Training School:

Once a patient was admitted to the Utah State Training School, it was

almost impossible for that patient to leave unless sterilization took

place first (Trent, pp. 221-222). A volunteer working at the

school in the 1930s remarked, “Some of the children seem a little sorry

about it… but most of them are eager to get it over with because they

are then given more opportunities to get out on their own”(Trent, p.

222).

Bibliography

English, Daylanne K. 2004. Unnatural Selections. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

Landman, J. H. 1932. Human Sterilization: The History of the Sexual Sterilization Movement. New York: MacMillan.

Ordover, Nancy. 2003. American Eugenics: Race, Queer Anatomy, and the Science of Nationalism. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

MRAU (formerly known as Mental Retardation Association of Utah). “About MRAU.” Available at < http://www.mrau.org/about_mrau.htm>

Nakao, Gary. 1974. “Sterilization and the Mentally

Retarded.” Doctoral Dissertation, Department of

Educational Psychology, University of Utah.

Painter, George. 2001. “The Sensibilities of Our Forefathers: The History of Sodomy Laws in the United States.” Sodomy Laws. Available at <http://www.glapn.org/sodomylaws/sensibilities/utah.htm>

Paul, Julius. 1965. "'Three Generations of Imbeciles Are Enough': State Eugenic Sterilization Laws in American Thought and Practice." Unpublished ms. Washington, D.C.: Walter Reed Army Institute of Research.

Ricks, Paul M. 1973. “Attitudes of Administrative and Professional Staff Personnel at the Utah State Training School Towards Sterilization of the Mentally Retarded.” Master's Thesis, Graduate School of Social Work, University of Utah.

Rosen, Christine. 2004. Preaching Eugenics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Trent Jr., James W. 1994. Inventing the Feeble Mind. Los Angeles: University of California Press.

“Utah State Hospital.” Available at <http://www.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~asylums/utah_ut/index.html>

“Utah State Prison.” Available at <http://www.cr.ex.state.ut.us/corrections/facilities/usp.html>