South

Dakota

Number of victims

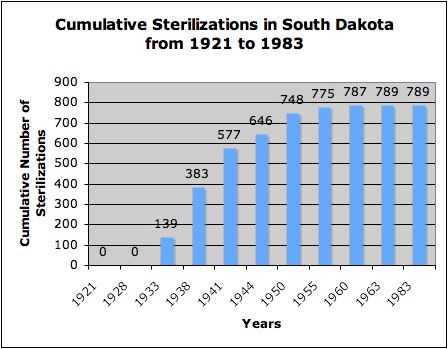

In South Dakota there were 789 victims of sterilizations. Almost two thirds of those sterilized were women, and the majority of these victims were considered to be mentally disabled. Those who sterilized that were not mentally disabled were considered “mentally ill.” In Comparison to other states with sterilization laws, South Dakota ranked 15th in total numbers of sterilization.

Period during which sterilizations occurred

Sterilizations occurred in South Dakota between the late 1920s and the early 1960s (see also Paul, p. 474).

Temporal

pattern of

sterilizations and rate of sterilization

After the passage of the sterilization law in 1917, there were no recorded sterilizations until the late 1920s. It is believed that the first of these sterilizations did not occur until 1929 (Paul, p. 273). From the early1930s to 1947 there was a steady rate of sterilizations, however, the number of sterilizations then quickly declined and leveled off to a total of 789 people. Between 1933 and 1950 the rate of sterilizations was about 6 people sterilized per 100,000 residents per year.

Passage of Law

South Dakota was the 15th

state to pass a

sterilization law in the United States. The first eugenic sterilization

law in the state was

passed in 1917. A South Dakota legislative bill was passed for the

“prevention

of the procreation of idiots, imbeciles, and feeble-minded persons.”

Unlike other states, the

bill only applied to one institution, the State Institution for

Feeble-Minded

in Redfield (Laughlin, p. 34). As Julius Paul noted, “the law was

compulsory

and lacked provisions for notice, hearing, or appeal of a sterilization

order."

There were challenges to the constitutionality of this law, so the

institution

did not make use of the law for close to fifteen years, even

though these challenges were never contested in the courts. The

state chose to amend the laws because it feared confrontation about the

legality of the policy (Landman, p. 79)

In 1925 an amendment was added to the sterilization law that established the authority of a State Commission for Control of the Feeble-Minded and county boards of insanity. This amendment gave the county boards of insanity the juristiction to sterilize residents of South Dakota not only within the State Institution for Feeble-Minded in Redfield, but also those who were "at large" in society (Chamberlain, p. 3). Another amendment in 1943 covered the sterilization of certain inmates at Yankton State Hospital (see below).

South Dakota repealed its compulsory sterilization law in 1974 (Coleman, p. 55).

Groups identified in the law

The original South Dakota bill was an act to sterilize “idiots,” “imbeciles,” and “feeble-minded persons” in the State Institution for Feeble-Minded in Redfield, thus preventing them from procreating and passing on their defects (Landman, p. 78). The 1925 law covered the “feeble-minded” and “insane” at large. Those at Yankton State Hospital suffering from mental illness, sexual perversion, and syphilis were identified under the 1943 amendment (Paul, pp. 469-70).

Process of the Law

According to the text of the 1917 bill, the basis for selection was dependent upon a procedure. The superintendent of the State Institution for Feeble-Minded in Redfield would examine a prospect’s mental and physical condition, the individual's records, and the family history of the inmate to determine whether it would be improper or inadvisable to allow the inmate to procreate. An annual report of the inmates was made to the State Board of Charities and Corrections. Along with the superintendent, the board would “carefully” examine each inmate’s record and write-up, and if a majority decided that it would be inadvisable to let the inmate procreate, then the physician of the institution, or another physician selected by him, would perform either a vasectomy or ligation of the fallopian tubes. Under the law the superintendent was to keep a record of all inmates operated on, with “statistics and notes or observations regarding its benefits, and make an annual report” to the Governor (Laughlin, pp. 34-35).

The 1925 law allowed for people

with mental

disabilities, outside of the Redfield Institution, to be subjected to sterilization decisions by the county

boards.

Paul notes that sterilization could be “either a quid pro quo for

avoiding

commitment, or for those already in the institution [in Redfield], a

basis for

release,” and it provided “for notice, hearing, and the right to appeal

to the

courts” (Paul, p. 469). He also indicates that anyone in the state could submit a

complaint to a county subcommission concerning a sterilization, upon

which an

at large person could be committed for segregation from the general

publication

or sterilization (Paul, pp. 469-70). If an at large member of society were to be operated they were to be given 15 days notice (Landman, p. 79)

In 1943, the law was amended so that inmates of Yankton State Hospital could be sterilized, provided they suffered from a) inherited mental diseases and were liable to pass them on to descendants; b) “perversion” of other departure from “normal mentality”; or c) a disease of a syphilitic nature (Paul, p. 470).

Precipitating factors and processes

The state’s motives were both

“therapeutic and eugenic”

(Laughlin, p. 13). During the time period in which the majority of the

sterilizations occured the population was decreasing, declining from

694,000 people in 1930 to 652,000 people

in

1950. This emigration was stimulated by the “commercialization in

agriculture, diminishing local control, and rural

migration” that occurred during this time (Dimit and Field, pp. 5-6).

Many of

the more affluent left the state to live in either California or the

Lakes

region to the East. This left a larger proportion of “feeble-minded,”

which

prompted people to take more action. Prosperity-depression

cycles affected the state after the boom of World

War I. The combination of droughts and the Great Depression brought

widespread

problems in the late 1920s and early 30s. Vigorous relief measures were

instituted under the New Deal. This decline in the economy created a

new desire

to “cleanse” the population. Also, in 1921 Congress passed the Snyder

Act to

establish free health care as a federal trust responsibility for tribal

members

of quarter-blood Indian heritage or more in all federally recognized

tribes.

This increase in medical awareness led to the assessment of many Native

Americans as “mentally ill” or “mentally deficient.” There may have

been a

higher proportion of Indians in the Redfield institution as the methods

of

mental retardation determination were skewed—those with more formal

education

did better on tests and may have appeared more intelligent.

Groups targeted and victimized

There is little information on the state institution’s population, which makes it hard to determine the groups targeted, but it is clear from the number of women sterilized in comparison to men that women were targeted. Nearly two-thirds of the people sterilized were women. There was also a high proportion of Native Americans in the hospitals, partially due to the 1921 Snyder Act that gave quarter-blood or more Native Americans free health care (Sisson and Zacher, p. 48). The subjective assessment of Native Americans due to lower levels of education and socialization may have led to a higher proportion of Indians in the Institution in Redfield. Thus, this would increase Native Americans chance of being selected for sterilization. There is no information on restrictions on those identified in the law or with disabilities in general related to abortion, marriage, etc. (Lawrence, p. 404).

Even after the compulsory sterilization law was repealed, Native Americans were still targeted for sterilization. Beginning in the 1960s and into the 1970s, many Native American women were "voluntarily" sterilized. However, many of these women were in fact misinformed about sterilizations, asked while under durress, or were coerced to be sterilized. After seeking help from the Interior Subcommittee on Indian Affairs, the Goverment Accounting Office (GAO) conducted a study that looked into the sterilizations of Native American women and found that amongst four reservation hospitals, one in South Dakota, there were approximately 3,406 sterilizations between 1973 and 1976. These involuntary sterilizations came to an end in 1976 when the Native Americans gained control of their health services (Torpy).

Major proponents

There

is very

little information available about major proponents of eugenics in

South

Dakota. It can be assumed that the executive agencies were the main

proponents

of eugenics, including the State Commission for Control of the

Feebleminded,

the county boards, the State Board of Charities and Corrections, and

the

Superintendent of the main institution. However, no definitive information is

available.

“Feeder institutions” and institutions where sterilizations were performed

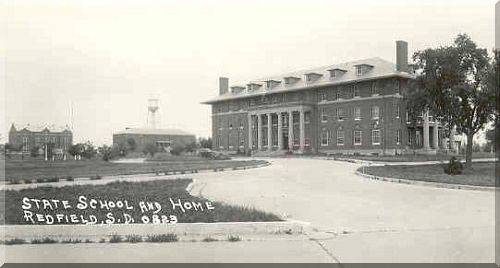

(Photo

origin: Hand County, South Dakota, Genealogy and Family Research

Center, available at

http://freepages.history.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~handcosd/Spink/album/redf-sch-2.html)

(Photo

origin: Hand County, South Dakota, Genealogy and Family Research

Center, available at

http://freepages.history.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~handcosd/Spink/album/redf-sch-2.html)

The main location where sterilizations were performed was the State Institution for Feeble-Minded, Redfield, whose main function of the institution was to house and monitor those classified as “feeble-minded.” In 1951 it became known as the State School and Home for the Feeble Minded. Following this, in 1989 it took the name South Dakota Developmental Center, which it is still called today. The South Dakota Developmental Center’s web site does not mention any involvement of the place with sterilizations (South Dakota Developmental Center).

Opposition

Although there is little information on opposition to eugenic sterilizations in South Dakota, Paul states that the Mental Health Committee of South Dakota doubted eugenics since not all instances of mental deficiencies are linked to heredity (Paul, p. 473). It is known, however, that religion was closely intertwined with education in the 1930s through the 1950s and it is likely that there was some opposition from religious leaders, as birth control was rejected in some of the Catholic regions. Also, small groups within the state that thought the sterilizations were too radical were also opposed (Sisson and Zacher, p. 48).

Bibliography

Chamberlain, Joseph P. 1929. "Eugenics in Legislatures and Courts." American Bar Association Journal 15,1.

Coleman, Sandra S. 1980. "Involuntarty Sterilizations of the Mentally Retarded: Blessing or Burden?" South Dakota Law Review, 25.

Dimit,

Robert M.,

and Donald R. Field. 1970. “Population Change in South Dakota Small Towns

and

Cities.” Unpublished paper. South Dakota State University.

Landman,

J. H. 1932. Human

Sterilization: The History of the Sexual Sterilization Movement.

New York:

MacMillan.

Laughlin,

Harry H.

1922. Eugenical Sterilization in the

United States. Chicago: Municipal Court of Chicago.

Lawrence, Jane. 2000. "The Indian Health Service and the Sterilization of Native American

Paul, Julius. 1965. “'Three Generations of Imbeciles Are Enough': State Eugenic Sterilization Laws in American Thought and Practice.” Washington, D.C.: Walter Reed Army Institute of Research.

“Redfield

State

Hospital and School.” Historic Asylums. Available at <http://www.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~asylums/redfield/index.html>.

Sisson,

Richard,

and Christian K. Zacher. 2007. The American

Midwest: An Interpretive Encyclopedia. Indiana: Indiana

University Press.

South

Dakota Developmental Center. “The History of SDDC.”

Available at <http://dhs.sd.gov/sddc/history.aspx>.

Torpy, Sally

J. 2007.

“Native American Women and Coerced Sterilization: On the Trail of Tears

in the 1970s.” American Indian Culture and Research Journal 24, 2: 1-22.