Oregon

Number of

Victims

2,341 sterilizations are recorded to have occurred in the state of Oregon from 1921 until 1983. However, in state governor John Kitzhaber's 2002 “Human Rights Day” apology on behalf of the state, it is noted that 2,648 people were sterilized (Josefson, p. 1). Of the 2,648 people accounted for, 1,713 (65%) were women and 935 (35%) were men. Victims, drawn mainly from state institutions like mental hospitals, facilities housing developmentally disabled persons, and prisons, were deemed mentally ill (about one third) or deficient, or in earlier time periods, “feeble-minded” (almost 60%).

Period

During Which

Sterilizations Occurred

The first Oregon Eugenics law was signed into law in 1917 and sterilizations began (Eccleston, p. 2). The rate of sterilizations was greatest during the 1920s and 1930s, yet substantial number of sterilizations did occur after the end of World War II. The Oregon eugenics program continued to sterilize people on occasion until the 1960s, with the law not being repealed fully until 1983.

Temporal Pattern and Rate of Sterilizations

Passage of

Law

Bethenia Owens-Adair, the public leader of Oregon's eugenics law (see below), authored and promoted a sterilization law in 1907. She continued to introduce it every year until it was finally passed and was signed into law in 1917 (Currey, pp. 47-50). The first law was passed in 1909 to “to prevent the procreation of confirmed criminals, insane persons, idiots, imbeciles and rapists,” by large margins in the Oregon Legislature (Largent, p. 192), but was vetoed by Governor Chamberlain as being overly complicated and not including enough safeguards for those convicted under it (Paul, p. 456).

In 1913, with the newly elected Governor West, the Oregon Legislature passed another eugenics bill that was signed into law. Opponents, led by the Anti-Sterilization League, gathered signatures and forced a referendum on the issue in the fall of 1913. The advocacy of the Portland-based Anti-Sterilization League was largely credited with ensuring the law was subjected to a referendum, and contributing to its defeat (Paul, p. 456). Member of that group argued that the law was overly broad and that supporters had not sufficiently proven that sterilization was an effective or necessary reform technique, pointing to the success of former prison-colony nation Australia (Largent, p. 193). Voters rejected the new law 53,319 to 41,767.

The lobbying effort for eugenics regrouped and continued vigorously (Owens-Adair, p. 71), and another law was passed and signed by Governor Withycombe in 1917 that created Oregon's Eugenics Board (Eccleston, p. 2). The law provided for the sterilization of all “feebleminded residents of state prisons and hospitals.” Public scrutiny was decidedly more muted as proponents tried to reframe the purpose of the law to voters mostly distracted by World War I (Largent, p. 194). The law was amended in 1919 to include an appeals process for patients and their families, and was codified into Oregon statute in 1920. In 1921, the Marion Circuit Court struck down, in Cline v. Oregon State Board of Eugenics, as unconstitutional Oregon's law as violating the U.S. Constitution's ban on cruel and unusual punishment. The case was brought by Jacob Cline, a rural farmer convicted of incestual child molestation, who according to law was examined at his state prison and found to have feeblemindedness and a sexual perversion. His lawsuit effectively ended eugenics in Oregon for a time (Largent, pp. 194-195). At that time, 127 patients had already been sterilized (Laughlin, pp. 147, 318).

A new law was passed and signed in 1923 that brought eugenics back to Oregon. Supporters stressed the new law as being non-punitive and therapeutic for both the patient and society, and it survived challenges even though the substantive language of the new law was almost entirely the same. The law permitted the sterilization of “persons, male or female, who are feeble-minded, insane, epileptic, habitual criminals, moral degenerates and sexual perverts, who are, or … who are likely to become, a menace to society” (Cruz). Owens-Adair pushed for the inclusion of provisions in the new law to target especially sexual offenses (Paul, p. 457). For the first time it was expanded to include all residents, regardless of institutionalized status. Similar efforts led the push for marriage limits on “deviants” (Laughlin, p. 343). In 1925 the Oregon Legislature passed an amendment to the eugenics law to include all those convicted of rape and sodomy to the statute (Landman, p. 77). Oregon’s laws were further legitimized with the 1927 United States Supreme Court decision, in Buck v. Bell, that upheld the federal constitutionality of eugenics (Largent, p. 195).

After slowly decreasing in speed, scope and scale since the 1950s, the Eugenics Board was renamed and reformed in 1967, and loosely disbanded in 1975 (Currey, p. 134). The last known sterilization order in Oregon occurred in 1978, and the State Eugenics Board considered no new cases after 1981. The Oregon Legislature repealed the 1923 law establishing legal eugenics in1983. The debate over the Governor’s aforementioned 2002 apology “has uncovered decades of lost records and unknown cases,” including at “least one woman died as a result of a forced hysterectomy” (Cruz).

Groups

Identified in

the Law

The earliest Oregon sterilization bill applied to all feeble-minded people “…to prevent the procreation of confirmed criminals, insane persons, idiots, imbeciles and rapists” (Largent, p. 192).

The later law used to sterilize people singled out, “…those feeble-minded, insane, epileptic, habitual criminals, moral degenerates and sexual perverts” (Laughlin, p. 146). It was worded broadly to encompass a large swath of society deemed unfit for procreation. The “mentally deficient” often had sterilization as a precondition for leaving the state’s institutions (Paul, pp. 458-459). “Rapists, and other insane people,” were a section vaguely worded, but intended to encompass sexual deviants that often fell victim to the scorn of the State Eugenics Board. Homosexual men were often the main targets of this (Boag, p. 210).

Process of

the Law

The process of the law required had state hospitals and prisons to review inmates and make recommendations to the State Eugenics Board for possible sterilizations. The Board itself was comprised of the directors of the four main institutions, the members of the State Board of Health and the Secretary of the State Board of Health. The Board would then review and make decisions on the validity of the inmate’s feeblemindedness. Members of the Board served without compensation (Laughlin, p. 88) and an order of sterilization required a majority vote (Landman, p.76).

Two

years after the initial 1917 law, a patient appeals

process was implemented so an inmate could appeal his or her

sterilization

order to the local county court within fifteen days (Largent, pp.

194-195).

Aforementioned changes to the law later allowed for non-incarcerated or

institutionalized people to be drawn into the process, thusly expanding

its

scope. Although all laws enacted throughout the early twentieth century

were compulsory, it was considered the policy of the Eugenics Board to

have the

consent of the patient and/or his guardians as to not provoke a popular

or

legal backlash. Even though a lack of appeal to a local court was often

seen as a sign of consent, if objection was raised anytime during the

process,

it was usually halted. This being said, it was often easy to obtain

consent

from families supportive of eugenics policy, or patients wishing to be

released

back into the general population (Paul, p. 458).

Precipitating

Factors

and Processes

The passage of a comprehensive eugenical sterilization law in Oregon traces its history back to Oregon's admittance to the Union. Leaders of "progressive movements” in Western states were main forces behind movements such as prohibition, suffrage, and social reform (Currey, pp. 86-89). Eugenical sterilization created what scholar David Noble called “a paradox of progressive thought” (quoted in Largent, p. 188), referring to the inherent contradiction between social reform and the damage caused by eugenics in America. Its development in Oregon followed a national backlash against what was perceived to be a widespread moral and racial decline. Immigration from southern and eastern Europe and the procreation of the “feebleminded” pushed a majority of states to approve sterilization laws in the first half of the twentieth Century. Prominent supporters of eugenics, like Harry Laughlin, were also big supporters of other laws to homogenize the United States racially, like the Immigration Act, 1924 (Largent, p. 189).

Groups

Targeted and

Victimized

Oregon’s laws targeted three main groups.

The first group, criminals and the insane, were people considered to lack that intelligence and the wit to groom children for a modern society. Such people were deemed simple and feebleminded and drawn mainly from state hospitals and small towns.

The second group, habitual criminals, was people convicted of three or more felonies, drawn mainly from state prisons and sometimes those who used sterilization as an avenue to again gain parole. They were seen as too risky for society in that they would undoubtedly raise families of ill and criminal regard.

The third and final group, were “sexual perverts and moral degenerates,” and came from both state prisons and hospitals (Largent, p. 195). The real separation of Oregon was in its especially virulent targeting of "sexual deviants." Although this included women at the margins of society, rapists and child molesters (Boag, p. 208), homosexual men were prosecuted and persecuted at higher rates (Owens-Adair, pp. 110, 183). Homosexual political and cultural scandals in Portland incited widespread outrage to homosexuality (Largent, p. 195), and as seen as a mental illness in the United States until the 1960s, was included under the charge of eugenics proponents.

Other

Restrictions

Placed on Disabled People

In Oregon, like other states with eugenics laws, sterilization was often a precondition of being released from prison or from a state mental institution (Paul, p. 458). It was often people at the margins of society who were targeted as feeble-minded or perverse, although who would in modernity be considered competent to mange a household, that consented to sterilization to regain their freedom. Even after release there was certainly a stigma associated with having been targeted by the Oregon Eugenics Board, based on the public characterizations made by eugenics proponents like Bethenia Owens-Adair. This stigma was often intense because the individuals targeted, like mentally ill people, homosexuals or troubled young women, would have naturally already been at the far periphery of societal approval.

Major Proponents

(Photo

origin: Oregon Historical Society; available at

http://www.ohs.org/education/focus/breaking-tradition.cfm)

(Photo

origin: Oregon Historical Society; available at

http://www.ohs.org/education/focus/breaking-tradition.cfm)

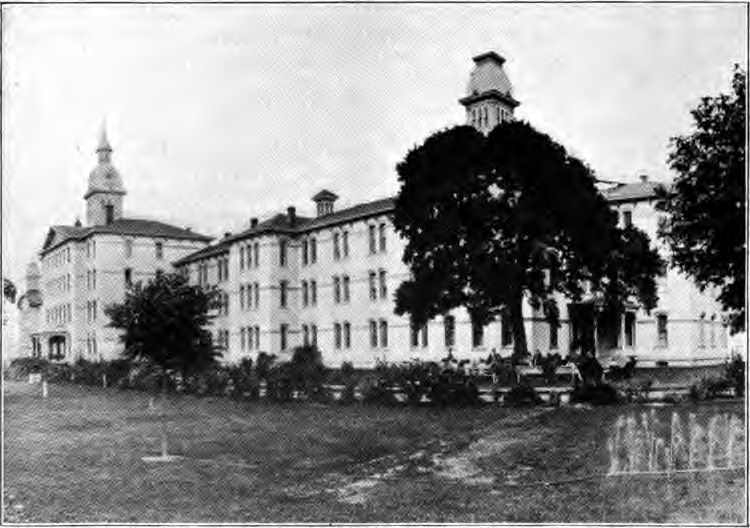

“Feeder institutions” and institutions where sterilizations were performed

(Photo origin: Wikipedia.com;

available at

http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Image:Oregon_State_Hospital_1920.jpg)

(Photo origin: Wikipedia.com;

available at

http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Image:Oregon_State_Hospital_1920.jpg)

The

Oregon State Hospital (formerly the Oregon State Hospital for the

Insane) was a

primary institution for sterilization; it is located in Salem

(Brockley, p. 24). The Oregon

State Hospital is open to this day and serves as the state’s primary

mental

health facility ("Oregon State Hospital"). There is no mention on the

Hospital’s website of its eugenical past (Oregon.gov).

(Photo origin:

Viamigo.com; available at

http://www.viamigo.com/img/l/tour/1608/description.jpg)

(Photo origin:

Viamigo.com; available at

http://www.viamigo.com/img/l/tour/1608/description.jpg)

The Oregon State Institute for

the Feeble-Minded, in Salem, was the largest center of eugenics

(Brockley,

p. 24), and closed in 2000 (Cruz). The Oregon State Institute for the

Feeble-Minded was later renamed the Fairview Training Center. Fairview was established by the legislature in 1907

and the institution

was created as a "quasi-educational institution" charged with

educating the "feeble-minded" and caring for the "idiotic and

epileptic" (Oregon Blue Book).

(Photo

origin: Wikipedia.com; available at

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Image:Oregon_State_Pen.JPG)

(Photo

origin: Wikipedia.com; available at

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Image:Oregon_State_Pen.JPG)

The happenings of these institutions, including a particular fondness for castration and salpingectomy over other less radical forms of sterilization (Laughlin, p. 88), are almost completely ignored only 25 years after the last law‘s repeal. Oregon’s eugenics program affected people from largely from the state’s institutions, institutions whose directors served on the State Eugenics Board. The progam extended to non-institutionalized people, who were the targets ofsocial workers and community complaints. The existences of "vice commissions" in larger cities were also responsible rounding up the periphery of society for the state's actions (Boag, pp. 10-11). Oregon was infamous for targeting largely targeted troubled or simply “misbehaving” youth and homosexual men (Cruz).

Opposition

Oregon also had a lively opposition movement that opposed the actions of the Eugenics Board and Owens-Adair. Portland had the nation's only "Anti-Sterilization League" (Laughlin, pp. 42-45) that opposed eugenics on grounds that it was biased, lacked scientific backing, and was inappropriately harsh and malicious in its doings. The voters, the legislature, a governor and the court system all at least one time rejected a eugenics law. Oregon’s initiative votes on eugenics could be the first and only eugenics referendum ever.

Lora Little, whose opposition to eugenics was influenced by her general opposition to the medical profession, chaired the Oregon Anti-Sterilization League. Her crusade had begun with the death of her son, whom she believed died from complications from the smallpox vaccination. Little found the medical profession a career based purely for-profit and full of radical and unsubstantiated claims of progress (Largent, p. 188).

The shift towards acceptance of eugenics was a refocusing in a frame of a therapy that helped people, and not a sentence for deviance. Oregon’s support of progressive ideas that embraced science in public policy made it hard to overcome the law’s widespread support. Protestant women’s groups led by Owens-Adair held much sway in the largely developing state, and traditional voices of opposition like conservatives and Catholics were underrepresented.

Bibliography

Boag, Peter. 2003. Same-Sex Affairs. Berkley: University of California Press.

Brockley, Janice. 1991. "Doctors, Deviants and Defectives: Sterilization in Oregon." Undergraduate Thesis, University of Oregon.

Cruz, Lawrence M. 2002. "Some Oregonians Have Sad Memories of Forced Sterilization." Statesman Journal (Dec.). Available at <http://www.people1.org/eugenics/eugenics_article_2.htm>.

Currey, Linda Lorraine. 1977. "The Oregon Eugenic Movement: Bethenia Angelina Owens-Adair." Master's thesis, Oregon State University. Available at <http://ir.library.oregonstate.edu/dspace/bitstream/1957/8301/1/Currey_Linda_L_1977.pdf>.

Eccleston, Jenette. 2007. "Reforming the Sexual Menace: Early 1900s Eugenic Sterilization in Oregon." Undergraduate Research Paper. Dept. of History, University of Oregon. Available at <https://scholarsbank.uoregon.edu/dspace/handle/1794/5917>

Josefson, Deborah. 2002. "Oregon Governor Apologizes for Forced Sterilizations." British Medical Journal 14, 325: 1380.

Largent, Mark. 2002. “The Greatest Curse of Race: Eugenic Sterilization in Oregon, 1909-1983.” Oregon Historic Quarterly 103, 2: 188-197.

Oregon Blue Book. "Fairview Training Center: Agency History." Available at <http://bluebook.state.or.us/state/executive/Mental_Health/fairview.htm>.

Oregon.gov. "The History of Oregon State Hospital." Available at <http://www.oregon.gov/DHS/mentalhealth/osh/main.shtml#history>.

Owens-Adair, Bethenia. 1922. Human Sterilization. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Paul, Julius. 1965. "'Three Generations of Imbeciles Are Enough': State Eugenic Sterilization Laws in American Thought and Practice." Washington, D.C.: Walter Reed Army Institute of Research.