North

Dakota

Number of victims

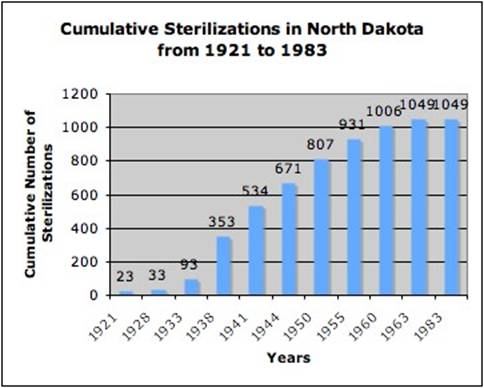

There were 1,049 victims of sterilizations in North Dakota. Of these 1,049 victims, 62% were women. 36% were considered mentally ill, and 60% were deemed “mentally deficient.” Compared to the other states with sterilization data, North Dakota ranked 12th in total numbers of sterilization.

Period during which sterilizations occurred

Sterilizations occurred in North Dakota between the 1910s and 1962 (see Paul, p. 639).

Temporal pattern of sterilizations and rate of sterilization

After the passage of the sterilization law in 1913, sterilizations occurred at a very conservative rate despite compulsory legislation. Up until January of 1930, only 39 sterilizations had been carried out. However, in the Depression years when financial woes took priority over mental institutions, there was a sudden rise in the number of sterilizations. In the peak years from 1933 to the end of 1943, a total of almost 580 operations were performed. The rate of sterilization in that period was 8 per 100,000 residents per year. High figures were reached again in the early 1950s.

Passage of Law

North Dakota’s sterilization law was enacted in 1913, after being passed in the House (73 to 20) and the Senate (34 to 4) and being signed into law by Governor L. B. Hanna. It was “an act to prevent procreation of confirmed criminals, insane, idiots, defectives, and rapists; providing for a board of medical examiners and making a provision for carrying out of same” (Laughlin, p. 26). This original version of the law lacked provision for notice, hearing and appeal rights. It was subsequently repealed and replaced in 1927 with a new law that provided notice, hearing, and appeal rights. In 1961, another revision of the law dropped epileptics from the bill. The law was repealed in 1965 (Paul, p. 638).

Groups identified in the law

The North Dakota bill was an act to prevent “confirmed criminals,” “insane,” “idiots,” “defectives,” and “rapists” from procreating.

Process of the Law

According to the text of the bill, the basis for selection was a procedure: Whenever the warden, superintendent, or head of a state prison, reform school, state school for the feeble-minded, or any state hospital or asylum certified in writing that he or she believes the patient/inmate was likely to give birth to children with criminal tendencies, the condition was not likely to improve, and/or procreation would be potentially detrimental to the community, a surgical sterilization could be brought into question. A board of examiners consisting of the chief examiner of the institution, the secretary of the state board of health, and one other physician or surgeon would have a meeting in which they would inquire into the mental and physical condition of each inmate and examine the family history of each inmate. If it was determined after each member of the board wrote up separate findings that there was a consensus, an operation would be designated and a tentative time and surgeon would be set up. Institutions were to keep all files of these proceedings and minutes of each meeting were to be written by the chief medical officer. If a patient were to request a sterilization, the physician could complete the surgery without going through the board of examiners. If the state attorney had reason to believe that any person convicted of a felony had been twice or more previously convicted of felonies, then the board of examiners would run through the same process described above (Laughlin, pp. 26-28). Another bill passed at the time defined the feeble-minded as not only those "properly classified" as feeble minded" but also persons "offensive to the public peace or to good morals, and who is a proper subject for classification and discipline in the institution" (Askvig, p. 93). In 1915, this definition was further expanded to include persons "whose defects prevent them from receiving proper training in the public schools" (Askvig, p. 93).

The 1927 law provided for the sterilization of the “feeble-minded, insane, epileptic, habitual criminals, and sexual perverts” (Landman, p. 67). Leaders of various state institutions for the “socially deficient” could recommend sterilization to the State board of examiners, consisting of three surgeons, which could conduct a hearing and make a decision (Landman, p. 67).

A further law was defeated in the North Dakota legislature that would have established a state registry for those deemed mentally defective. "All persons with such a designation [were to] be listed in a card catalog in each county clerk's office. This list would then [have been] used to restrict various legal acts, such as land purchases, lawsuits, and most specifically marriage. No person listed in the card catalog would [have been] allowed to purchase a marriage license" (Askvig, p. 94). The central registry was proposed by Dr. Lamont, then superintendent of Grafton (see below), in 1940 (Askvig, pp 20).

Precipitating factors and processes

The state’s motive was deemed by eugenicist Harry Laughlin to have been “mainly eugenic, also therapeutic” (Laughlin, p. 11). During the time period with the most sterilizations (the mid 1920s through the 1930s), an economic Depression sped up the initially conservative rate of sterilizations. The North Dakota Depression started with the collapse of wartime grain prices in 1920. Many farmers had been making large investments and were industrializing their farms in the years immediately preceding the Depression. The Depression effectively “punctured” the financial expansion from the past decades. In 1921, a record number of banks closed which led to many farm foreclosures (Remele, p. 3). These setbacks led to a sharp rise in sterilization operations, likely due to more financial pressure to lower costs in institutions. Many institutions were full and waiting lists were continuing to grow. By sterilizing inmates, those that were only being confined due to potential procreation of genetically “defective” offspring could be allowed to leave, making room for more and/or saving scarce money. Operations after the war years (and the Depression) dropped from the highs of the 1930s with no consistent trend. Another reason for the increase in sterilizations in the late 1920s was an alteration to the 1913 law, which changed from no notice, hearing, or appeal rights to required notice, hearing, and appeal rights. This made anyone who was originally uneasy about the law to be more comfortable, as patients were given more rights.

Groups targeted and victimized

There is

little

information on the hospital’s population, which makes it hard to

determine the definitive

groups targeted. However, from the overall numbers of sterilizations it

is

clear that women and those classified as “mentally deficient” were

overrepresented in the sterilization numbers. Over 62%

were women, an

overrepresentation of approximately 12%. Over 60% were “mentally

deficient,”

nearly double the number classified as “mentally ill.” There is no

known

information about race, ethnic, or religious sterilization numbers. It

is

possible that North Dakota overrepresented Native Americans

(particularly

women) like its southern border state, South Dakota. There

is no information on restrictions on those identified in the law

or with disabilities in general related to abortion, marriage, et

cetera.

Major proponents

There

is little information available

about major proponents of eugenics in North Dakota. It is known that

once a Social Service Department had been established at the State

Institute of the Feebleminded in Grafton (see below) in 1929, which

among other things was responsible for the suvervision of discharged

and paroled residents there, the two heads, Henrietta Safley and Evelyn

Jonston became promotors of eugenic sterilizations (Askvig, pp. 18-29).

During the peak period of sterilizations from 1933-1938, Dr. James P.

Alylen was the superintendent at Grafton (see below).

“Feeder institutions” and institutions where sterilizations were performed

There

were two

main institutions at which sterilizations took place.

(Photo

origin: Institute for Regional Studies, North Dakota State University

Libraries, Fargo; available at

http://digitalhorizonsonline.org/cdm4/item_viewer.php?CISOROOT=/uw&CISOPTR=2886&CISOBOX=1&REC=18)

(Photo

origin: Institute for Regional Studies, North Dakota State University

Libraries, Fargo; available at

http://digitalhorizonsonline.org/cdm4/item_viewer.php?CISOROOT=/uw&CISOPTR=2886&CISOBOX=1&REC=18)

The

main

institution to report operations was the Institution for the

Feeble-Minded in

Grafton, North Dakota (see Paul, p. 636), as it was the main

institution for

the feeble-minded and the majority of sterilizations were done on this

group.

Over 60% of sterilizations in North Dakota were done at this

institution (634

out of a cumulative 1,049 up to January of 1964) (Paul, p. 636). It

later

changed its name to Grafton State School and then North Dakota

Developmental

Center, and it may close in the next few years.The institutional

history One Hundred Years addresses sterilization at the institution

(Askvig, pp. 18-21).

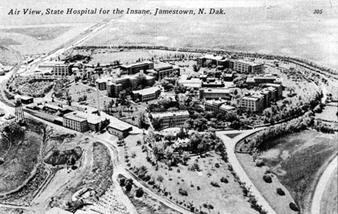

(Photo origin: USGenWeb Archives, available at http://www.usgwarchives.org/nd/stutsman/postcards/sthosp.jpg)

(Photo origin: USGenWeb Archives, available at http://www.usgwarchives.org/nd/stutsman/postcards/sthosp.jpg)

The

Hospital for

the Insane in Jamestown, North Dakota, was run by Dr. Wm. M. Hotchkiss at

the time

of the initial sterilization law. In this hospital many of the early

sterilizations happened. According to a Dr. Hotchkiss, the hospital was

short-staffed and under-budgeted, slowing the process. “I have had no

difficulty in securing the consent of parent or relative when patient

refuses

to have the operation performed…[yet] we have done much less [i.e.,

fewer operations]

than contemplated, because the lack of finance prevented the hiring off

surgical nurses” (Laughlin, p. 87). This was said in March of 1918,

before the

new State Board of Administration came into office. According to the

next

superintendent, the new State Board of Administration was opposed to

eugenic

sterilization and many relatives were opposing it, which led to a halt

of

sterilizations at the hospital.

Opposition

There is little information on opposition to the sterilizations in North Dakota. It is clear from the fact that sterilizations were very conservative in the initial decade after the 1913 law was passed that there was public and individual uncertainty about the sanctity of the law. Although some superintendents were adamantly pro-sterilization, there were many who were less active and more cautious about the sterilization selection procedure and actually completing the operations. It is also clear that during times of economic downturn and financial pressures, people became less likely to question the sterilizations. Most sterilizations were done during the Depression era, when people cared less about those in institutions and more about feeding their own families. When it became difficult to feed, clothe, and house their own, the interests of those who contributed relatively less to society were put below their own.

Bibliography

Askvig, Brent A. 2004. One Hundred Years: The History and Chronology of the North Dakota Developmental Center. Minot: North American Heritage Press.

Cole,

Janell. 1999. “N.D. State Hospital's History Marked by Politics.”

In-Forum

Fargo-Moorhead (October 24). Available at <http://

www.in-forum.com/specials/century/jan3/week44.html>.

Landman,

J. H. 1932. Human

Sterilization: The History of the Sexual Sterilization Movement.

New York:

MacMillan.

Laughlin, Harry H. 1922. Eugenical

Sterilization in the United States. Chicago: Municipal Court

of Chicago.

North Dakota Developmental Center. “Developmental

Center Accreditation,

Certification, and Background information.” Available at

<http://www.nd.gov/dhs/locations/developmental/accreditation/index.html>.

Paul, Julius. 1965. “‘Three Generations of

Imbeciles are Enough’; State

Eugenic Sterilization Laws in American Thought and Practice.”

Washington, D.C.:

Walter Reed Army Institute of Research.

Remele, Larry. 1988. “North Dakota History:

Overview and Summary.”

Available at <http://

www.nd.gov/hist/ndhist.htm#bibliography>.