Kentucky

Number

of victims

There

were no victims, as Kentucky did not have a eugenic sterilization law.

Passage

of law(s)

While

no eugenic sterilization law existed, in the late 1920s a bill for

eugenic

sterilization was passed in the House but not the Senate after adoption

of a eugenic sterilization law had been recommended by the Kentucky

Board of Charities and Corrections (Noll, p. 77).

Precipitating

factors and processes

In

1860, the State Institute for the Feeble-Minded in Frankfort opened,

which made

it one of the earliest such institutions in the entire South (see Noll,

pp. 12,

161 n. 22), but it provided only custodial care for a small number of

inmates

and eventually became overcrowded (Noll, p. 23).

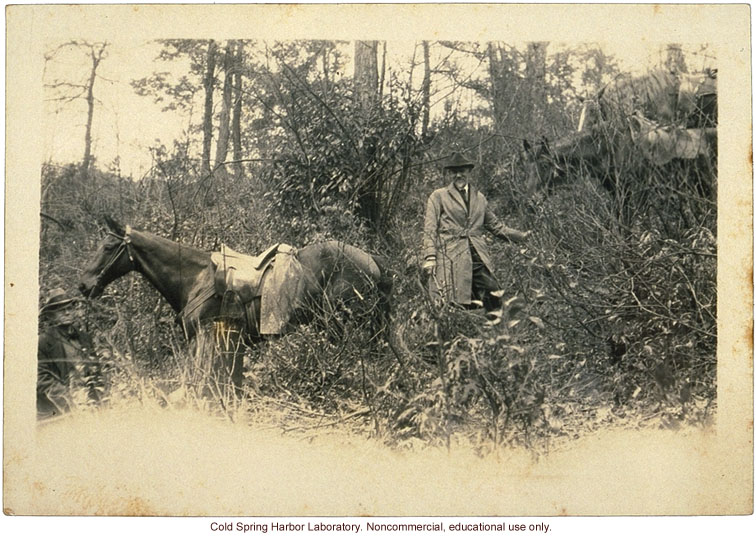

In the late 1910s and early 1920s Kentucky was of interest to eugenicists. Charles Davenport conducted studies there (see picture); Kentucky was were included in Arthur Estabrook’s “Tribe of Ishmael” study; and in 1922 repealed its Pauper Idiot Pension Law, which had law authorized payments of seventy-five dollars per year to the families of poor and feeble-minded individuals in the community (Noll, p. 23). It was also one of the states in which the National Committee for Mental Hygiene conducted its survey regarding "feeble-mindedness" (Noll, p. 16).

(Photo origin:

Eugenic Archives, available at

http://www.eugenicsarchive.org/html/eugenics/static/images/1679.html)

(Photo origin:

Eugenic Archives, available at

http://www.eugenicsarchive.org/html/eugenics/static/images/1679.html)

A statute from 1934 referenced the need for sterilization based upon the propogation of the "socially inadequate" that was occuring and that would ultimately lead to "race suicide." Skinner, the author, said that this problem was easily fixed via a simple and "harmless" operation that was actually to the benefit of the patient, who did not have, in Skinner's opinion, the capacity to rear children, anyway (Skinner, p. 168).

The Eugenics movement has also, recently, been analyzed in conjunction with the birth control movement (Meyer). The rise of birth control also came about as a result of science and had an effect on women. In the 1920's, religious groups attacked birth control, a movement that was fought by eugenicists and feminists, among others. Eugenics was used to support the birth control movement and its potential to restrict the reproduction of the "unfit" (Meyers, pp. 66-70). For example, Clarence Gamble, a physician and an advocate for birth control, supported the movement "not from a belief that women should have reproductive control, but from his desire to reduce the reproduction of the poor" (Meyers, p. 71). Interestingly, the Kentucky State Department of Health did not adopt birth control as an institutionalized service until 1966, though a movement to make that happen began in 1933. Despite that, there was a eugenicist presence in Kentucky. Advocates for birth control used the slogan "Fewer Babies, Better Babies" and received support from eugenicists such as Clarence Gamble (Meyers, pp. 71-74).

Other restrictions on people with disabilities

General

concerns about marriage and feeblemindedness became

apparent in 1913 at the Protestant Episcopal General Convention. It was there that the Kentucky

Diocesan

Convention reported that it had drafted and passed the resolutions that

required health certificates to be presented before people could get

married

(Rosen, p. 63). The

idea of so called

“eugenic marriage legislation” looked appealing in the early 1910s, but

the Health Certificate legislation ultimately failed (Rosen,

p. 69).

Opposition

A

eugenics organizer credited Catholic groups in Kentucky with having

helped to stall a eugenic sterilization law (Rosen, p. 145).

Bibliography

Estabrook, Arthur H. 1923. "The Tribe of Ishmael." In Eugenics, Genetics and the Family, vol. 1. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins Co.

Meyers, Judith Gay. 2005. A Socio-Historical Analysis of the Kentucky Birth Control Movement 1933-1943. Louisville, KY: University of Kentucky.

Noll,

Steven. 1995. Feeble-Minded

in Our Midst: Institutions for the

Mentally Retarded in the South, 1900-1940.

Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

Paul,

Julius. 1965. "'Three Generations of Imbeciles Are

Enough': State Eugenic Sterilization Laws in American Thought and

Practice." Washington, D.C.: Walter Reed Army Institute of Research.

Rosen, Christine. 2004. Preaching Eugenics: Religious Leaders and the American Eugenics Movement. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Skinner, George T. 1934-1935. Sterlization Statute for Kentucky. 23 Ky. L.J. 168. Excerpt available here: HeinOnline