Kansas

Number of victims

In

total, 3032 individuals were sterilized in Kansas, 58% of which were

male. In terms of

the total number of

sterilizations, Kansas ranks 6th in the United

States. Many more

people with mentally illnesses (2,063) than people who were considered

“mentally deficient” (856) were sterilized.

Period during which sterilizations occurred

Sterilizations

legally began in 1913 and ended in 1961 (Paul, p. 627). There were a

few cases of sterilization before it was legalized, however. The

superintedent of the Kansas

State

Home for the Feebleminded at Winfield, Dr. F. Hoyt Pilcher, performed

58

castrations, and even as many as 150 sterilizations in total. This

process

began in 1894 and ended several years later when Pilcher was removed

from his

administrative position (Paul, p. 617; Wehmeyer, p. 58).

Temporal pattern of sterilizations and rate of sterilization

Passage of law(s)

In

1913, the Kansas legislature passed the first sterilization law in the

state. Many felt

that the law was

problematic, and thus its enforcement was less than stellar (Paul, p.

618). In an attempt

to make the process

of the law easier, a second law was passed in 1917 which eliminated

some of the

work for the institutions (Paul, p. 619).

Groups identified in the law

The

1913 legislation was directed at “habitual criminals, idiots, epileptics,

imbeciles, and

insane” (Paul, p. 618). The

1917 law

targeted the same groups, but eliminated the courts’ approval from the

decision

(Paul, p. 619).

Process of the law

The first law required institutions to examine all who

were

identified as belonging to the aforementioned categories (Paul, p. 618). These authorities then

made recommendations

to the district or state courts, which made the final decisions

regarding

sterilization (Landman, p. 68). This

law

contained no provisions for the court processes such as hearings or

appeals

(Paul, p. 618). The

1917 law did away

with the role of the courts, instead creating a board of examiners

composed of

the authorities from the institutions as well as the secretary of the

State

Board of Health (Paul, p. 619). Under

this law, the inmate was given advance notice of his hearing, at which

he was

allowed to provide a case for defense.

After studying the case and hearing the arguments, the

board had the

final authority in the question of sterilization (Landman, p. 69).

Precipitating factors and processes

In

spite of carrying out sterilizations in the absence of a state law,

Hoyt

Pilcher was re-appointed as the superintendant of the Kansas State Home

for the

Feeble-Minded in Winfield in 1897, in part due to Kansans’ widespread

fears of

a “flood” of degenerates that would engulf the state (Paul, p. 618). However, up until 1925, a

conservative

portion of the population held onto fears related to Pilcher’s

sterilizations

and the political outcry they caused.

After the infamous Buck v. Bell case in 1927, public

approval of

sterilization increased greatly, causing an enormous rise in the rate

of

sterilizations in Kansas (Paul, p. 619).

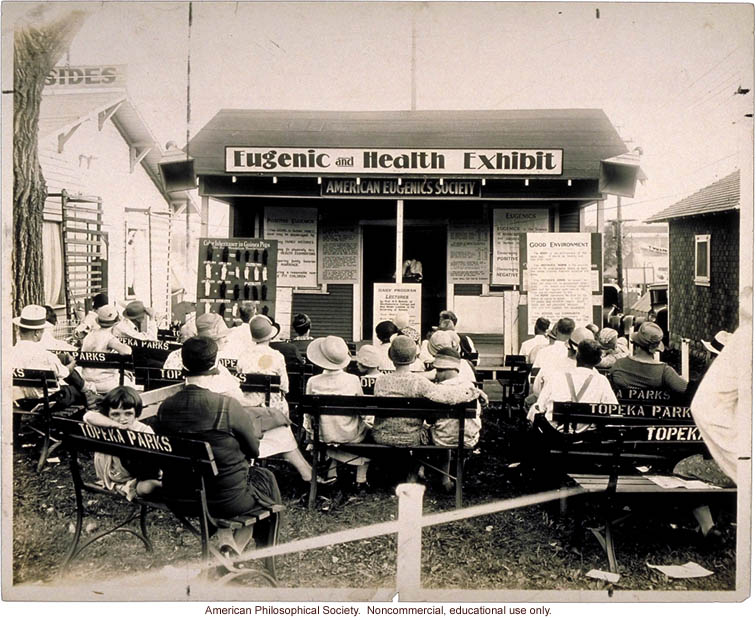

Another important factor that contributed to the popular acceptance of sterilization legislation was the existence of the “Fitter Families” contest that started at the Kansas State Fair, but quickly spread to other states. Pictured above, these competitions encouraged families to “breed” superior children that would fit the rigid judging standards. The Fair was heavy with propaganda, and helped to normalize the idea of genetic superiority and inferiority (Lovett, p. 5). The idea of “eugenic marriages” began to take hold with the popularity of the Fitter Families contest. These marriages, designed to breed the most desirable offspring, began with a marriage in Iola, Kansas (Michael, p. 20).

In 1903, Kansas also passed a miarriage restriction law, which did not

apply to those women over the age of 45, under the pretense that it was

no longer likely that those women would bare children. Breaking the law

and marrying someone who was deemed unfit (alcoholic, feeble minded,

etc.) resulted in up to a $1,000 fine or three years in prison

(Woodward, p. 71).

Groups targeted and victimized

In

addition to those with intellectual disabilities and the mentally ill,

habitual

criminals were also a targeted group (Paul, p. 618).

Other Restrictions Placed on Those Identified in the Law or With Disabilities in General

In

addition to laws regarding sterilization, several marriage restriction

bills

were proposed in Kansas as part of the eugenics movement. Although they were never

enacted as state

law, marriage bills were proposed in 1915, 1917, and 1927,

demonstrating the

popularity of eugenic ideals (Michael, p. 20).

Major proponents

Florence

Sherbon, a physician who specialized in the reduction of infant

mortality, was

a major proponent of the “Fitter Families” contest at the Kansas State

Fair.

Sherbon used these fairs to popularize eugenic theory, hoping to

engrain the

idea that those with more desirable traits were morally and physically

superior

to those who, for example, were not as intelligent or good-looking. Sherbon favored long,

involved examinations

in the evaluations of the family members, whereas some of his

colleagues

encouraged shorter, more intensive testing.

Eventually Sherbon developed a widely accepted system for

the

examinations: a short exam for the fairs, a longer one for the Fitter

Families

Examination Center, and an even more involved exam for those families

wishing

to submit their information for Eugenic record-keeping (Lovett, pp.

9-17).

“Feeder institutions” and institutions where sterilization were performed

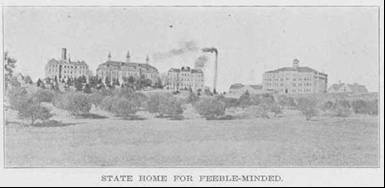

(Photo

origin, Kansas: a cyclopedia of state history; available at

http://skyways.lib.ks.us/genweb/archives/1912/f/feeble-minded_state_home.html)

(Photo

origin, Kansas: a cyclopedia of state history; available at

http://skyways.lib.ks.us/genweb/archives/1912/f/feeble-minded_state_home.html)

Perhaps the most famous site of sterilizations in Kansas is the

Winfield State Hospital. The Winfield State Hospital opened

initially in 1881 on the University of Kansas campus but soon relocated

to the town of Winfield in 1887, receiving the name change "The Kansas

State Asylum for Idiotic and Imbecile Youth" and had thirty-one

students (Seaton, p. 252). The new location, further away from the more

public University of Kansas central campus, allowed for the Asylum to

become more self sufficient, using the young students as an indentured

work force, raising vegetables, meat, grain, having its own water, and

even putting out its own fires instead of relying on the public fire

departments (Seaton, p. 252).

On July 1, 1893, Dr. F. Hoyt Pilcher was named the superintedent of the

Asylum, after an increase in the number of students. This is the point

at which the eugenics movement began to have a greater influence on the

Winfield Institute with the Progressive movement. In

this state home

Pilcher “de-sexed”

his patients (Paul, p. 617), no longer focusing on simply keeping the

"feeble-minded" in the institution, but sterilizing them so that, in

the event that they left the institution, they would not enter society

sexually. The number of students at the Institute began to grow at an

exponential rate. "In 1900 it was 173, and in 1910 it was 419. By 1916

it was 589" (Seaton, p. 253).

In 1909 the name changed to the State

Home for the Feeble-Minded, after many of the epileptics in the

institution had been sent to the newly founded Parsons Institute which

attempted to use newly discovered medical treatments for

epilepsy.

It is important to note that the original emphasis of the Winfield Institute was education, training those at the Institute to live in society. By the 1920s, however, the emphasis was placed on agricultural productivity as both the male and female clients were put to work throughout the institution, so that it could become its own system. no longer training the students to live in society, but training them to live in their own self-created world. By 1933 it was called a “custodial institution for the helpless” and the emphasis was on discipline, cost-cutting, and farm productivity, which included a name change again in 1930 to the State Training School. . At this time, further sterilizations occurred (Seaton, p. 254). The population at Winfield peaked during WWII when it reached 1,245 clients in 1942 (Seaton, p. 254).

After

WWII, Kansas hospitals for the disabled were assessed and several

problems were found at Winfield. Although there were not recorded

accounts of physical abuse, handcuffs, leg irons, and whips were found

in the hospital and in February 1987, 14 employees were fired and 13

were suspended after claims of client abuse in the men’s wards (Seaton,

p. 257). In 1991, after a long history of turmoil at Winfield,

the governmental process of closing the hospital’s doors began.

It was part of a movement fostered by the idea that the developmentally

disabled had civil rights that should be protected. Finally, in

March 1998, after much debate, Winfield closed its doors, and it is now

a correctional facility

(Seaton, p. 261; Kansas Department of Corrections). The

hospital’s closing seems long coming, as throughout Winfield’s 116-year

existence, it continuously suffered from “an uncertain mission, a

troubled relationship with the state and the community, and

overcrowding due to almost nonexistent admission policies” (Seaton, p.

263). Today, three community-based programs serve more than 250

clients in Cowley County, and more than 100 of them came from Winfield

(Seaton, p. 261).

(Photo origin: Rootsweb.ancestry.com; available at http://www.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~asylums/topeka_ks/index.html)

(Photo origin: Rootsweb.ancestry.com; available at http://www.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~asylums/topeka_ks/index.html)

Topeka State Hospital: At least early on, most of the sterilizations took place in the State Hospital in Topeka (Laughlin, p. 70). This hospital opened in 1879 after the Ossawatomie State Hospital, once thought to be sufficient, became overcrowded with mentally ill inmates. The hospital closed in 1997, but the building still exists and is currently not in use.

The Beloit Industrial School for Girls was a place where female misfits were to be educated for their re-entry into society. It received significant negative press in Kansas, especially in the 1930s, when reports of sterilizations of a large portion of its inmates emerged for which the process of the law appeared to have been circumvented. The reason for such action was simple: female delinquency, for which the inmates were punished in this fashion (Michael, pp. 21-27). It is currently used as a juvenile correctional facility (Kansas Juvenile Justice Authority).

Opposition

Much of the opposition to the sterilization legislation in Kansas came in the form of conservatives who felt that involvement in the procedures was much too complicated and could lead to legal implications. However, after Buck v. Bell, much of this opposition ceased (Paul, p. 619). It is also notable that in Kansas, not all Progressives were in support of sterilization legislation. Famed Pulitzer-Prize winning journalist and author William Allan White led a sizeable oppositional group of Progressives against the eugenics movement (Michael, p. 9).

Bibliography

Kansas Department of Corrections. "Winfield Correctional Facility." Available at <http://www.dc.state.ks.us/facilities/wcf>.

Kansas Juvenile Justice Authority. 2008. "Benoit Juvenile Correctional Facility." Available at < http://www.kansas.gov/jja/Facilities/Beloit_Facility/>

Landman,

J. H. 1932. Human Sterilization: The History

of the Sexual Sterilization Movement.

New York: MacMillan.

Laughlin,

Harry H. 1922. Eugenical Sterilization in

the United States. Chicago: Municipal Court of Chicago.

Lovett,

Laura L. "'Fitter Families for Future

Firesides': Popular Eugenics and the Construction of a Rural Family

Ideal in

the United States." Unpublished paper. Dept. of History, University of Massachusetts.

Available at

<http://www.yale.edu/agrarianstudies/papers/PopularEugenics.pdf>

Martin,

Roger. 2004. "The History of Eugenics

in Kansas." Topeka Capital-Journal (Jan. 23). Available at

<http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_qn4179/is_20040123/ai_n11808086>.

Michael,

Philip. 2004. "Kansas

Eugenics." Undergraduate Senior Thesis, Department of History, McPherson College.

Paul, Julius. 1965. “‘Three Generations of Imbeciles Are Enough’: State Eugenic Sterilization Laws in American Thought and Practice.” Unpublished manuscript. Washington, D.C.: Walter Reed Army Institute of Research.

Seaton, Frederick D. 2004-2005. "The Long Road Toward 'The Right Thing to Do': The Troubled History of Winfield State Hospital." Kansas History 27: 250-63.

Kansas State Board of Administration. 1928. Procedure to Be Followed in Sterilization Cases. Topeka, Kansas: Board of Administration.

Wehmeyer,

Michael L. 2003. "Eugenics and

Sterilization in the Heartland." Mental

Retardation 41, 1: 57-60.

Woodward, Masten. 2002. “Kansas' Eugenics Movement.” Master's Thesis, Department of History, Kansas State University.