Home

Stuttgart (Städtische Kinderkrankenhäuser und Kinderheime Stuttgart)

Current historical scholarship (see Topp 2004, 2005; also Benzenhöfer

2000) establishes the existence of a Kinderfachabteilung in Stuttgart

beginning January 1943 at

the latest until at least July 1944, if not the end of

WWII. The Städtische

Kinderheime und Kinderkrankenhäuser in Stuttgart consisted of a complex

of several

associated children's hospitals and homes and had their

administrative headquarters in the Birkenwaldstr. 10. The special

children's ward was not physically separated from other

wards but rather spread out over several facilities. Dr. Karl Lempp

was the clinic's director (he was also the city's deputy director

of the municipal public health department), and Dr. Magdalene Schütte

was responsible for the special children's ward.

Source: author.

Even though after WWII the American military government in Stuttgart

in 1946 suspected Dr. Lempp

"of having been involved in eliminating

people

with hereditary

disorders in collaboration with

Dr. Stähle

[as assitsant secretary responsible for medical

affairs in the Ministry of the

Interior in Wurttemberg],“ his proceedings before a German denazification

tribunal (Spruchkammerverfahren) resulted in his

classification of a "Mitläufer"

(passive follower), the second-lowest

category on a five-item scale of culpability. The committee saw

it as "proven that he had not been involved in the extermination of

unworthy life." In 1948 both Dr. Lempp and Dr. Schütte provided

testimony in the investigaton of the state prosecutor leading up to the

Grafeneck trial at the Landgericht Tübingen in 1949 against Dr. Stähle and Dr.

Mauthe (the former's highest medical

deputy in the Ministry of the Interior), in which the court held that

after preliminary communications in November 1942 between the two and

Dr. Hans Hefelmann and Richard von Hegener of the Reichsausschuss about

establishing

a special children's ward in Wurttemberg, the involved parties

"ultimately refrained from doing so," although the court established

that 93 children were transferred to special children's wards outside

of Wurttemberg (Bauer, p. 94). Thereafter Dr. Lempp remained deputy

director of the municipal

public

health department until 1949 and was director of the municipal

children's clinic until 1950, at year when he retired. He died in 1960.

Dr.

Schütte worked as a pediatrician in Aalen and was head physician of the

children's department of the regional hospital in Aalen between 1947

and 1956. In 1963 the state attorney's office in Stuttgart conducted

investigations against Dr. Schütte, which were terminated in the same

year.

While Ernst Klee, Udo Benzenhöfer, and Sascha Topp in their research

have argued for the existence of a special children's ward, Rolf

Königstein (2004) has strongly denied it. He documents the above

investigations and events and finds them to be exculpatory, even in

regard to the fact that at the time of the investigations against Dr.

Schütte in 1963, it had become known that she had signed on 30 June

1944 a request for Luminal from Dr. Widmann at the KTI (Topp 2005, p.

55. n. 272; with reference to BAB, R 58/1059, Bl. 64). He finds Dr.

Schütte's assertion credible that such requests were made to deceive

the Reichsausschuss, and he notes that neither Dr. Lempp nor other

clinic personnel received Sonderzuwendungen(special

allocations

for their involvement in the killing; Königstein,

p. 473). He does not mention, however, that such a deception is not

known to have been asserted as a defense of the charge of collaboration

with the Reichsausschuss in this matter in any other similar

circumstance, nor has

it been found credible by other scholars, and he does not seem to be

aware of the fact that not all of the directors of clinics with special

children's wards and their head physicians received such special

allocations.

Moreover, Peter Sandner (p. 536) reports that Dr. Schütte requested,

after consultation with Richard von Hegener [of the Reichsausschuss],

in

early 1943 to visit Eichberg "in order to get to learn its methods of

treatment." Eichberg, like Brandenburg-Görden, not only was the

location of a Kinderfachabteilung but also doubled up as training

facility where new

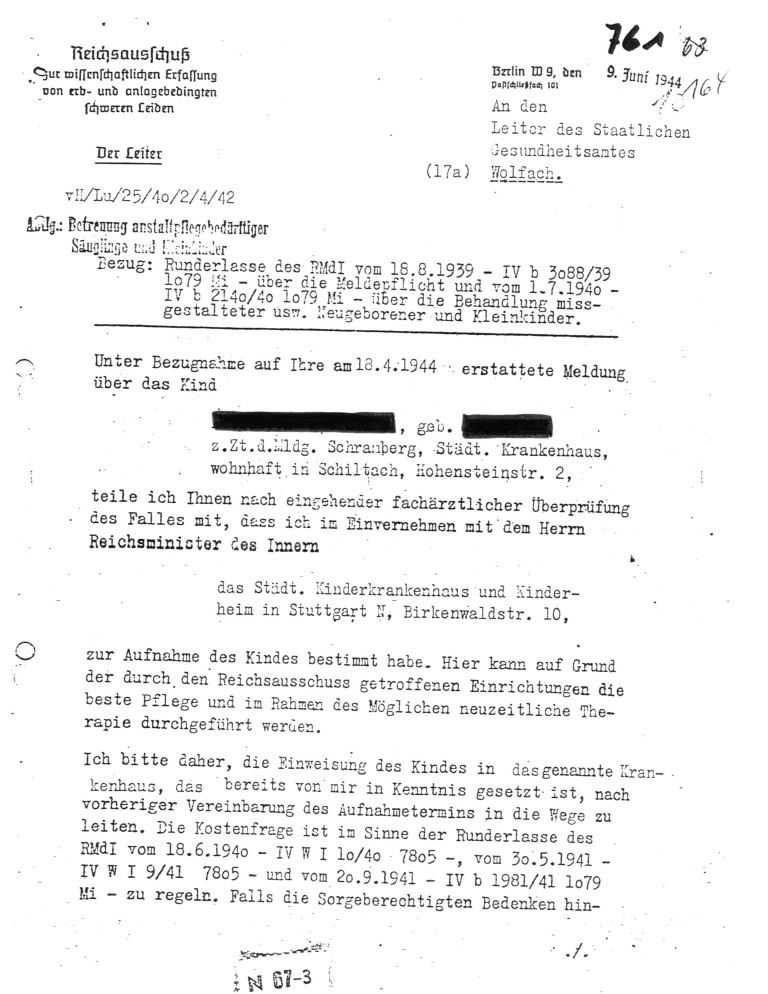

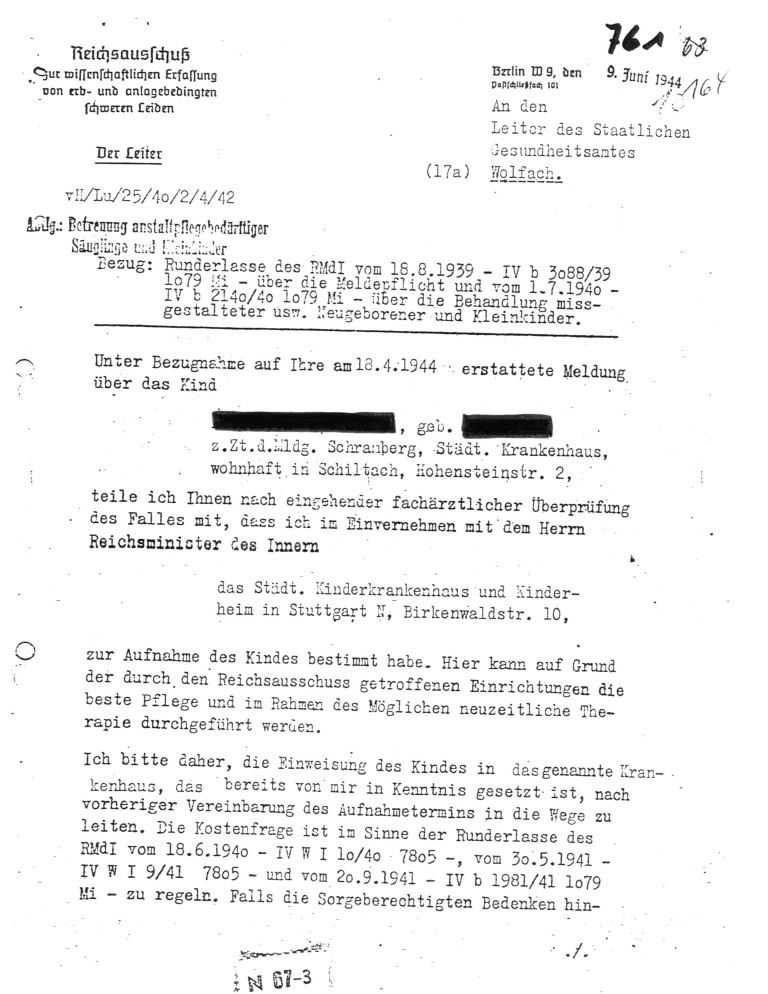

"euthanasia" physicians could learn their trade. Furthermore, a

document collected by the State Attorney's office in Gera in its

investigations against Rosemarie Albrecht (in Platz/Schneider, p. 81)

shows a correspondence from the Reichsausschuss to the public health

department of a city in Baden about a child to be admitted to the

Städtisches Kinderkrankenhaus und Kinderheim in Stuttgart,

Birkenwaldstr. 10. This documents alludes to the possibility that when

the state attorney's office explored the involvement of public health

departments in Wurttemberg in children's euthanasia in 1948-49, it may

not have taken account of the possibility that children from

territories adjacent to Wurttemberg were admitted to the

Kinderfachabteilung Stuttgart. In this context it should be noted that

for another clinic with a similar arrangement, i.e., a formally open

hospital with a decentralized killing ward whose children blended in

easily with the general hospital population, Dortmund-Aplerbeck,

post-war investigations erroneously concluded that no

children's ward had existed when in fact, as was discovered in the late

1980s, such a ward did exist and the

death of 162 children remains unexplained.

Source: Platz/Schneider, p. 81.

Source: Platz/Schneider, p. 81.

The most convincing evidence for the existence of a Kinderfachabteilung

in Stuttgart has been marshalled by the physician Dr. Marquart (2008,

2009, 2011a-d). Based on his analysis of 506

extant

death certificates of children who died in the children's

hospital between January 1943 and the end of April 1945, he finds 52

suspicious deaths of children diagnosed with severe innate disorders -

but for which no causal relation to their death can be established. One

third of the children died of pneumonia, a typical result of poisoning

with Luminal. The death certificate was sometimes signed with a

fake name.

For a long time, apart from a recent stumbling block in Stuttgart-Vaihingen

for

Gerhard Durner, a child victim of "children's euthanasia" who died at

the Eichberg facility, there is no commemoration of children's

euthanasia in

Stuttgart - a city that harbored so many Nazi luminaries and

profiteers. A grandson of Dr. Lempp even threatened legal

action against Dr. Marquart and the publisher of the book Stuttgarter

NS-Täter.

In 2013 a stumbling block was placed for the child victim Gerda

Metzger. A youtube video is available: http://youtu.be/HoioDFctXbM? More information about the victim can

be found here.

Literature

Bauer, Fritz et al., eds. 1968-1981. Justiz

und NS-Verbrechen: Sammlung

deutscher Strafurteile wegen nationalsozialistischer Tötungsverbrechen,

1945-1966. Amsterdam: University Press Amsterdam. Vol. 5, p.

87ff.

Benzenhöfer, Udo. 2003. "Genese und Struktur der 'NS-Kinder- und

Jugendlicheneuthanasie.'" Monatsschrift

für Kinderheilkunde 151: 1012-1019.

"Karl Lempp." In Wikipedia.de. At http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Karl_Lempp.

Königstein, Rolf. 2004.

"Nationalsozialistischer „Euthanasie“-Mord in Baden und Württemberg."

Zeitschrift für Württembergische Landesgeschichte 63:381-489.

Marquart, Karl-Horst. 2008. "Gab es in Stuttgart

eine 'Kinderfachabteilung'?" Paper presented at the Frühjahrstagung des

Arbeitskreises zur

Erforschung der nationalsozialistischen 'Euthanasie' und

Zwangssterilisation, Grafeneck, June 2008.

———. 2009. "Karl Lemp: Verantwortlich für

Zwangssterilisierungen und 'Kindereuthanasie.'" Pp. 100-7 in Stuttgarter

NS-Täter: Vom Mitläufer bis zum

Massenmörder, edited by Hermann G. Abmayr. Stuttgart:

Schmetterling Verlag. Available here.

———. 2011a. "Die Stuttgarter Opfer der

NS-'Kindereuthanasie.'"Pp. 110-18 in Verlegt:

Krankenmorde 1940-1941 am Beispiel der Region Stuttgart, edited

by Elke Martin. Stuttgart: Verlag Peter Grohmann.

———.

2011b. "Obermedizinalrat Karl Lempp, verantwortlich für

Zwangssterilisierungen und die 'Euthanasie' von Kindern." Pp. 124-32 in

Verlegt: Krankenmorde 1940-1941 am

Beispiel der Region Stuttgart, edited by Elke Martin. Stuttgart:

Verlag Peter Grohmann

———. 2011c. "Untersuchung über Stuttgarter Opfer der

NS-'Kindereuthanasie.'" Pp. 165-174 in Den

Opfern einen Namen geben: NS-"Euthanasie"-Verbrechen,

historisch-politische Verantwortung und Erinnerungskultur.

Munster: Klemm und Oelschläger.

———. 2011d. "'Kindereuthanasie' in Stuttgart:

Verdrängen statt Gedenken?" Pp. 145-168 in Kindermord

und "Kinderfachabteilungen" im Nationalsozialismus: Gedenken und

Forschung, edited by Lutz Kaelber and Raimond Reiter. Hamburg:

Lang.

Platz, Werner E., and Volkmar Schneider, eds. 2008. Dokumente einer Tötungsanstalt: "In den

Anstalten gestorben." Vol. 2. Hentrich und Hentrich.

Sandner, Peter. 2003. Verwaltung

des Krankenmordes. Der Bezirksverband Nassau im Nationalsozialismus.

Giessen: Psychosozial-Verlag.

Topp, Sascha. 2004. “Der ‘Reichsausschuss zur

wissenschaftlichen

Erfassung erb- und anlagebedingter schwerer Leiden’: Zur Organisation

der Ermordung minderjähriger Kranker im Nationalsozialismus 1939-1945.”

Pp. 17-54 in Kinder in der

NS-Psychiatrie, edited by Thomas Beddies and Kristina Hübener.

Berlin-Brandenburg: Be.bra Wissenschaft.

———. 2005. "Der 'Reichsausschuß zur wissenschaftlichen Erfassung erb-

und anlagebedingter schwerer Leiden': Die Ermordung minderjähriger

Kranker im Nationalsozialismus 1939-1945." Master's Thesis in History,

University of Berlin.

Source: Platz/Schneider, p. 81.

Source: Platz/Schneider, p. 81.