Home

Sachsenberg (Heil und Pflegeanstalt Sachsenberg)

The Kinderfachabteilung at the Heil- und Pflegeanstalt Sachsenberg was

established in August 1941 and continued until at least the end of 1944

(possibly until the end of WWII). The institution's director was Dr.

Johannes Fischer; in

charge and responsible for the "special children's ward" was Dr. Alfred Leu

(see Topp, pp. 34-5; Benzenhöfer, p. 1017). Dr. Fischer committed suicide

after WWII, whereas Dr. Leu fled to Holstein in the west, where he was

subsequently put in British internment until 1948 and in 1949 worked as a

forensic physician. Two anonymous letters pointing to his involvement in

"euthanasia" arrived and prompted an investigation (see Klee 2004, pp.

209-11).

Source:

http://www.hauspost.de/hp_online_1999_05/s/klinik.html

Source:

http://www.hauspost.de/hp_online_1999_05/s/klinik.html

A first trial in Schwerin in 1946 took place in the absence of Dr. Leu, and

the physician and nurses charged at the trial implicated Dr. Leu in the

killing of about 100 children (see Rüter). In two other trials in Cologne in

1951 and 1953, the court referred to the transfer of the children's station

in the nearby Lewenberg facility in July/August 1941 due to its requisition

by the German army to the clinic at the Sachsenberg with 280 children as the

possible beginning of the children's "euthanasia." According to Dr. Leu, the

Reichsausschuss had provided authorization for treatment for 180 children,

but by Dr. Leu's own account, he had negotiated down that number to about

100, killed "only" 70 of them and another 20-30 children subsequently, but

only to prevent another physician to take his place and kill even more. In

short, Dr. Leu, by his own account, was a true hero and savior who

reluctantly had to sacrifice a few to accommodate the demands of authorities

so he could save the many. The court gave credence to his views and issued a

verdict of not guilty twice. Subsequently, in the German Democratic Republic

there appears not to have been much interest in addressing the conditions

and events at the clinic during the NS-period (see Brooks 2007, pp. 25-26).

When the writer Helga Schubert attempted to use files related to

NS-"euthanasia" at the clinic in Schwerin in preparation for her book

(Schubert 2003), in which she reflected on 179 patient files of T4 victims

that were among the nearly 30,000 files discovered in Berlin in 1990

but did not focus on children, she was not granted access to them. A small

group of clinic employees in the early 1990s had founded the "Freundeskreis

Sachsenberg" and attempted to explore the history of the clinic further,

which led to a small exhibit detailing the history of the clinic, including

the NS period, in the mid 1990s (today remnants of an exhibit in the former

water tower only cover the period prior to 1933). In 1997 a plan was devised

to establish a memorial, which was furthered by the activities of a group

"Memorial activities in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern" (Gedenkstättenarbeit in

Mecklenburg-Vorpommern) of the association Politische Memoriale e.V., but

the Freundeskreis Sachsenberg then became inactive for some time (Pink 2008;

see also the following reports: 1, 2). According to a 1999 report written by Dr.

Schmidt-Degenhard, the director of the clinic at the time, for a magazine of

Schwerin, 430 children died at the Sachsenberg between 1941 and 1945, of

whom 300 are believed to have been victims of children's "euthanasia."

With a new clinic director, Dr. Andreas Brooks, taking office in 2003,

further changes were afoot. The first symposium on the Nazi past, under the

title "Events on the Sachsenberg during National Socialism" (Geschehnisse

auf dem Sachsenberg zur Zeit des Nationalsozialismus), took place on 25

January 2007. It was organized by the HELIOS-clinics, the Landeszentrale für

politische Bildung Mecklenburg-Vorpommern (state office for political

education), and the associations Politische Memoriale and Freundeskreis

Sachsenberg (Political Memorial and Friends of the Sachsenberg). A report

can be found here. This gave new life to the Freundeskreis

Sachsenberg and led to an invitation to artists to submit proposals for a

memorial. 14 such proposals were submitted, and in December 2007 the winner

was chosen: the proposal by the artist Dörte Michaelis.

The second symposium took place on 11 March 2008, supported by the

HELIOS-clinics and the Landeszentrale für politische Bildung

Mecklenburg-Vorpommern. Its title was "Medical Crimes in Schwerin during

National Socialism" (Medizinverbrechen in Schwerin in der Zeit des

Nationalsozialismus). A report can be found here.

Catalina Colom Gottwald's dissertation may address the topic of "euthanasia"

at Sachsenberg; she has published some preliminary findings (Lange 2009).

Dr. Lothar Pelz (2009) has provided the most extensive analysis of the

children so far. According to his analyses, 467 children and youths were

committed to the special children's ward between 1941 and 1945 (station IV -

"Abteilung IV der Anstalten Sachsenberg-Lewenberg"), and 284 died. A book by

Joachim Piper (2011) addresses the fate of disabled children who were cared

for by Lobetal deaconesses and sent to the children's home Lewenberg and to

the Sachsenberg's "Kinderfachabteilung."

Source: http://www.hauspost.de/hp_online_2004_02/s/27.htm

Trial courts established that about 180 children were transferred from the

children's home at the Lewenberg to the Sachsenberg, and that the transfer

in September 1941 coincided with the establishment of the special children's

ward there. Until April 1943, "72 physically healthy children of compulsory

school age [schulpflichtig]" remained at the Lewenberg facility, in a school

housed in the historical "Basedow house." All but 28 of the students were

transferred to the Sachsenberg facility, and the rest of the children

followed in November 1943, at which time no children were left on the

grounds of the Lewenberg. The school on the Sachsenberg grounds had enrolled

students between April 1943 and 1945 (Kasten 2013). The "Kinderheim

Lewenberg" as such did not cease to exist but only changed location to the

Sachsenberg facility and continued to operate under this name from there

during WWII.

Source: author

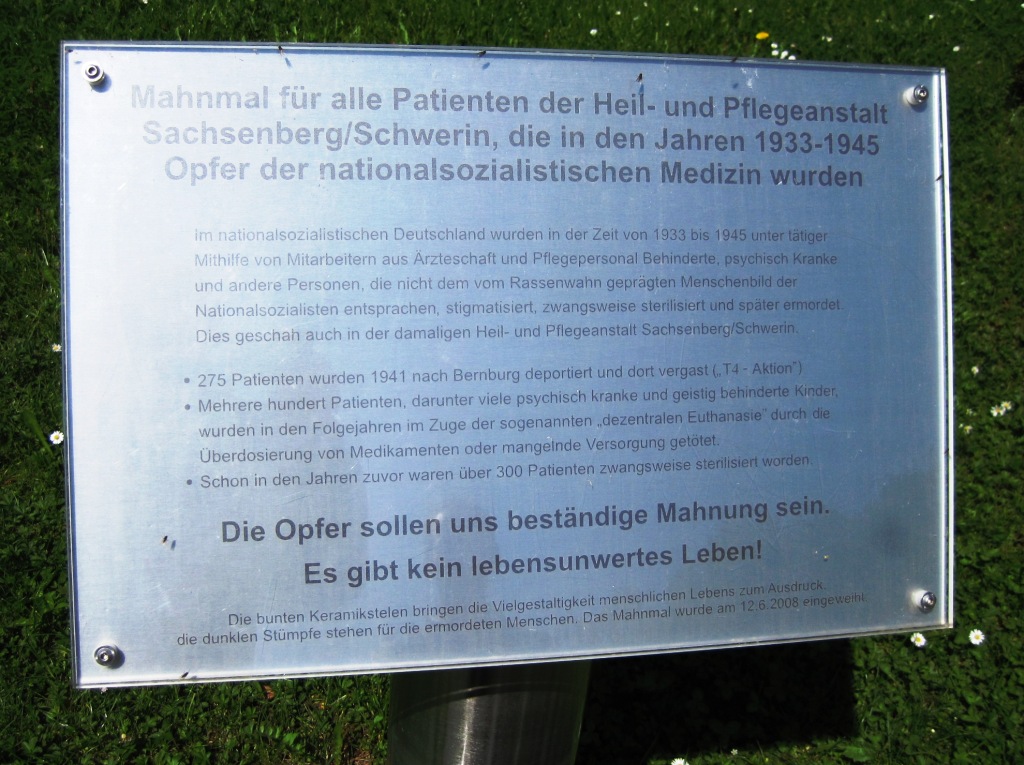

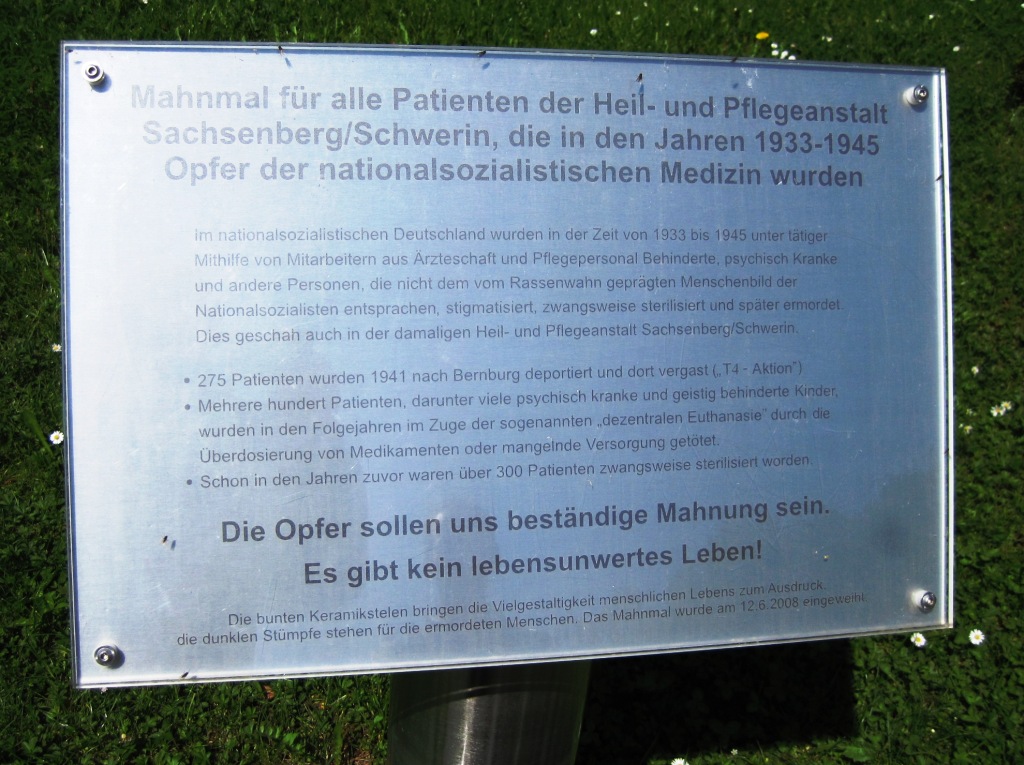

The artist Michaelis's memorial project was dedicated on 12 June 2008. It is

a series of ceramic stelae. The memorial is entitled

"Ein-Zum-Nachdenken-Bewegendes Werk" (a creation that moves one to think)

and meant to memorialize the more than 1,000 persons who were killed here or

transported from here to their death. It is meant to depict the diversity

and vivaciousness of life, together with the loss of life incurred by the

"euthanasia" crimes, signified by black, shortened stomps.

A text display that accompanies it, and was contributed mainly by Andreas

Wagner of the association Politische Memoriale, reads as follows: "Memorial

for all patients in the mental hospital Sachsenberg/Schwerin, who became

victims of Nazi medicine in the years 1933-1945. - In Nazi Germany during

the period 1933 to 1945 with the active assistance of staff from the medical

and nursing staff people with disabilities, the mentally ill, and other

persons who did not conform to the human image shaped by the Nazis racial

delusions were stigmatized, compulsorily sterilized, and later murdered.

This also happened in the former mental hospital Sachsenberg/Schwerin. -.

275 patients were deported in 1941 to Bernburg and gassed ('T4-program').

Several hundred patients, many of them mentally ill and mentally disabled

children were killed in subsequent years as part of the so-called 'wild

euthanasia' by overdose of medication or lack of care. In the preceding

years more than 300 patients had been forcibly sterilized. The victims

should be our constant reminder: There is no life that is unworthy of

living! The colorful ceramic stelae express the diversity of human life, the

dark stumps represent the murdered people. The memorial was established on

12 June 2008" (Mahnmal für alle Patienten der Heil- und Pflegeanstalt

Sachsenberg/Schwerin, die in den Jahren 1933-1945 Opfer der

nationalsozialistischen Medizin wurden. - Im nationalsozialistischen

Deutschland wurden in der Zeit von 1933 bis 1945 unter tätiger Mithilfe von

Mitarbeitern aus der Ärzteschaft und Pflegepersonal Behinderte, psychisch

Kranke und andere Personen, die nicht dem vom Rassenwahn geprägten

Menschenbild der Nationalsozialisten entsprachen, stigmatisiert, zwangsweise

sterilisiert und später ermordet. Dies geschah auch in der damaligen Heil-

und Pflegeanstalt Sachsenberg/Schwerin. - 275 Patienten wurden 1941 nach

Bernburg deportiert und dort vergast ("T4-Aktion"). Mehrere hundert

Patienten, darunter viele psychisch kranke und geistig behinderte Kinder

wurden in den Folgejahren im Zuge der sogenannten "dezentralen Euthanasie"

durch Überdosierung von Medikamenten oder mangelnde Versorgung getötet.

Schon in den Jahren zuvor waren über 300 Patienten zwangsweise sterilisiert

worden. Die Opfer sollen uns beständige Mahnung sein. Es gibt kein

lebensunwertes Leben! Die bunten Keramikstelen bringen die Vielgestaltigkeit

menschlichen Lebens zum Ausdruck, die dunklen Stümpfe stehen für die

ermordeten Mitmenschen. Das Mahnmal wurde am 12.6.2008 eingeweiht).

The display thus explains the meaning of the monument and the events, and it

puts them in historical context. The special children's ward is not

mentioned, and its victims are subsumed under the category victims of "wild

euthanasia."

On 27 January 2009 the first commemoration on the Holocaust remembrance day

took place, and on the same day in 2010, the second, with about 120

attendees. Reports can be found here and here.

The clinic's

website has a page on the clinic's history. It refers to the events

during the Nazi period, including the killing of children (here).

Source: author

Existing scholarship does not address the burial place for the children. The

facility's old cemetery looks overgrown.

Source: http://www.wismar.de/media/custom/125_1515_1_g.JPG?1257338042r>

A Stolperstein exists in Wismar for a child that died in the special

children's ward: Günter Nevermann (here; here). A scientific article is available (Haack et al.

2013).

Source: Gramenz 2013, p. 335

A child considered a "Mischling" under Nazi racial

policy died as a "euthanasia" victim on the Sachsenberg in 1942. His name

is Horst Ladewig (see Gramenz 2013, pp. 328-36).

Source:

http://www.focus.de/regional/mecklenburg-vorpommern/geschichte-sellering-erinnert-an-nazi-verbrechen-an-kindern-aus-luebtheen_aid_1024757.html;

http://www.ndr.de/regional/mecklenburg-vorpommern/gedenkstaette157.html

Piper (2011) states that for 56 children who were

transferred from the Lobetal facility, of whom 44 have

been identified as victims of "euthanasia," a memorial installation

was placed in Lübtheen (now the home of the charitable institution that

once cared for the children). It was opened to the public on 24 June 2013.

New research by Haack, Hässler, and Kumbier (2014; see

also Haack and Kumbier 2014) shows the "special children's ward" to have

been established on 19. Aug. 1941. They confirm Pelz's number of 284 who

died there. They also provided detailed information about the children

transferred from the Lobetal facility.

Literature

Benzenhöfer, Udo. 2003. "Genese

und Struktur der 'NS-Kinder- und Jugendlicheneuthanasie.'" Monatsschrift

für Kinderheilkunde 151: 1012-1019.

Brooks, Andreas. 2007. "Die Geschehnisse auf dem

Sachsenberg im Rahmen des nationalsozialistischen Euthanasieprogramms."

Pp. in Schweriner Gespräche,

edited by the Landeszentrale für politische Bildung

Mecklenburg–Vorpommern. Schwerin: Thomas Helms Verlag.

Endlich, Stefanie, Nora Goldenbogen, Beatrix Herlemann, Monika Kahl, and

Regina Scheer. 2002. Gedenkstätten für die Opfer des

Nationalsozialismus, vol. 2. Bonn: Bundeszentrale für politische

Bildung. Available at http://www.bpb.de/files/AFQX24.pdf.

Gramenz, Jürgen. 2013. Ladewig:

Dokumentation eines jüdischen Familienverbandes aus Mecklenburg.

Plaidt: Cardamina.

Haack, Kathleen, Frank Hässler, and Ekkehardt Kumbier. 2013.

"Nationalsozialistische 'Kindereuthanasie': Das Beispiel Günter Nevermann."

Zeitschrift für Kinder- und

Jugendpsychiatrie und Psychotherapie 41(3): 173-79.

———. 2014. "'Kindereuthanasie' in Mecklenburg: Zum Schicksal der

'Sonnenlandkinder' aus Lobetal (Lübtheen)." Trauma

und Gewalt 8 (4; Nov.): 286-93.

Haack, Kathleen, and Ekkehardt Kumbier. 2014. "Verbrechen an psychisch

Kranken und Behinderten in Mecklenburg während der NS-Zeit." Trauma

und Gewalt 8 (4; Nov.): 272-84.

Kasten, Bernd. 2013. Personal communication.

Klee, Ernst. 2001. Deutsche Medizin im

Dritten Reich: Karrieren vor und nach 1945. 2d ed. Frankfurt:

Fischer.

———. 2004. Was sie

taten, was sie wurden: Ärzte, Juristen und andere Beteiligte am Kranken-

und Judenmord. 12th ed. Frankfurt: Fischer.

Lange, Catalina. 2009. "Umsetzung der zentralen und

dezentralen Euthanasie in der Heil- und Pflegeanstalt

Schwerin-Sachsenberg." Pp. 46-58 in Ethik

und Erinnerung: Zur Verantwortung der Psychiatrie in Vergangenheit und

Gegenwart, edited by Ekkehard Kumbier, Stefan J. Teipel, and

Sabine C. Herpertz. Lengerich: Pabst Science Publishers.

Pelz, Lothar. 2009. "Mecklenburgische Kinderarzte und

NS-'Kindereuthanasie.'" Pp. 59-69 in Ethik

und Erinnerung: Zur Verantwortung der Psychiatrie in Vergangenheit und

Gegenwart, edited by Ekkehard Kumbier, Stefan J. Teipel, and

Sabine C. Herpertz. Lengerich: Pabst Science Publishers.

Pink, Jörg. 2008. "Der Verein 'Freundeskreis Sachsenberg' e.V. und die

Aufarbeitung der Geschehnisse auf dem Sachsenberg während der Zeit des

Nationalsozialismus: Zur Geschichte der Entstehung des Gedenkzeichens." Zeitgeschichte regional: Mitteilungen aus

Mecklenburg-Vorpommern 12 (2): 110-12.

Piper, Joachim. 2011. "Lobetal

habe ich säubern lassen": Arbeit und Schicksal der Lübtheener

Diakonissen. Celle: Lobetalarbeit.

Schmidt, K. 1935. "Geschichte und Aufgaben des

Kinderheims Lewenberg." Psychiatrisch-Neurologische

Wochenschrift 37: 16-20.

Schmidt-Degenhard, Michael. 1999. "Geplantes Mahnmal soll an die Schweriner

Opfer der Euthanasie erinnern: 900 Menschen mußten sterben." Hauspost:

Das Schweriner Stadtmagazin 5. Available at http://www.hauspost.de/hp_online_1999_05/s/klinik.html

Schubert, Helga. 2003. Die

Welt da drinnen: Eine deutsche Nervenklinik und der Wahn vom "unwerten

Leben." Frankfurt: Fischer.

Topp, Sascha. 2004. “Der ‘Reichsausschuss zur wissenschaftlichen Erfassung

erb- und anlagebedingter schwerer Leiden’: Zur Organisation der Ermordung

minderjähriger Kranker im Nationalsozialismus 1939-1945.” Pp. 17-54 in Kinder

in der NS-Psychiatrie, edited by Thomas Beddies and Kristina Hübener.

Berlin-Brandenburg: Be.bra Wissenschaft.

———. 2005. "Der 'Reichsausschuß zur wissenschaftlichen

Erfassung erb- und anlagebedingter schwerer Leiden': Die Ermordung

minderjähriger Kranker im Nationalsozialismus 1939-1945." Master's Thesis

in History, University of Berlin.\

Concerning

"Euthanasia" trial(s) for this location

Bauer, Fritz et al., eds. 1968-1981. Justiz

und NS-Verbrechen: Sammlung deutscher Strafurteile wegen

nationalsozialistischer Tötungsverbrechen, 1945-1966. Amsterdam:

University Press Amsterdam. No. 383.

Bryant, Michael S. 2005. Confronting

the "Good Death": Nazi Euthanasia on Trial, 1945-1953. Boulder:

University of Colorado Press. Pp. 198-203.

Mildt, Dick de. In the Name of the

People: Perpetrators of Genocide in the Reflection of Their Post-War

Prosecution in West Germany: The 'Euthanasia' and 'Aktion Reinhard'

Trial Cases. The Hague: Martinus Nuhoff Publishers. Pp. 176-9.

Rüter, Christiaan F. 2002-. DDR-Justiz

und NS-Verbrechen. Sammlung ostdeutscher Strafurteile wegen

nationalsozialistischer Tötungsverbrechen. Amsterdam: University

Press Amsterdam. No. 1832.

Last updated on 21 Feb. 2015

Source:

http://www.hauspost.de/hp_online_1999_05/s/klinik.html

Source:

http://www.hauspost.de/hp_online_1999_05/s/klinik.html