Tavid Bingham

Greek Tragedy

Euripides Bacchae

Background

The Bacchae

was the last tragedy of Euripides and produced after the playwright’s death by

his son in the year 405 BCE.

Likely the play was completed after Euripides had angrily left Athens

for the court of Macedon where he died (406/7BCE). Euripides had been criticized in Athens for being critical

and perhaps even against religion.

The Bacchae seems to be a

response to this, as Euripides presents an apparent defense of religion and

tradition.

The Bacchae

was the last tragedy of Euripides and produced after the playwright’s death by

his son in the year 405 BCE.

Likely the play was completed after Euripides had angrily left Athens

for the court of Macedon where he died (406/7BCE). Euripides had been criticized in Athens for being critical

and perhaps even against religion.

The Bacchae seems to be a

response to this, as Euripides presents an apparent defense of religion and

tradition.

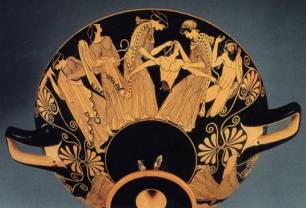

In fact, many scholars have interpreted the Bacchae as being a direct criticism on what was then a new

and rising intellectual movement known as sophism. Sophism emphasized logical and rational thinking that discounted

irrational religious and traditional practices. Euripides uses the god Dionysus (pictured here) as a vehicle

to present this subject. The plot

is full of paradoxes that raise many questions about religion, specifically

about the Dionysian religion that was perhaps the best example of faith

clashing with rationality.

Plot Synopsis

The

play opens with a prologue (lines 1-63) by Dionysus himself, who explains that

he has returned to his home of Thebes in order to punish the sisters of his

mother, who dishonored him by doubting his godliness. He has made the women of the city go mad and sent them to

dance crazily on Mt. Kithairon, as members of his cult would. He then ushers the chorus onto the

stage to speak the opening parados (lines 64-166). The chorus of Maenads (female worshipers of Dionysus) pay

high praises to Dionysus, telling of the freedom and delight that he has

brought them. Next, in the first

episode (lines 170-369) the men of the city including the seer Tiresias, the old

king Cadmus and his son Pentheus commiserate about the rebellious women, and it

becomes that Pentheus wishes to amass an army to lead up the mountain to

reclaim the women and in effect, battle Dionysus. The chorus re-enters and pays more praises to Dionysus and

in their first ode (lines 370-432) make it clear that Pentheus is most unwise

to dishonor the god further.  In the second episode (lines 433-518) Dionysus is

brought before Pentheus disguised as an attractive foreign agent of the

cult. The two argue about the

religion and Pentheus realizes that his prisoner is quite clever. The chorus then appeals (lines 519-575)

to Dionysus to come join them in their dithyrambic dance so that he may defend

them and the cult from the attack that Pentheus is waging. Next, Dionysus cunningly persuades

Pentheus to quietly sneak up the mountain and spy on the crazed Maenads, luring

the young prince into a trap (lines 576-861). Then the Maenad chorus erupts into another ode

of ecstasy (lines 862-911) in which they reflect on the stupidity of men, and

their habit of provoking the gods to punish them. This punishment is quickly approaching during the fourth

scene (lines 912-976) and then the fourth stasimon (lines 977-1023), as the Dionysus

and Pentheus approach the maenads (pictured above), and as the chorus becomes

fervent with excitement as the moment of Bacchus’ vengeance comes close. In the fifth episode (lines 1024-1152)

a messenger returns to Thebes and reports that Pentheus was ripped apart by the

maenads, and it was none other then his mother, Agave, who ripped off his

headed and danced with it, thinking it was a lion’s. The final brief choral ode (lines 1153-1164) rejoices at

Dionysus victory. The exodos

(lines 1165-1392) then has Agave return to Thebes and realize that she has in

fact killed her own son. Dionysus

then appears as a deity and reveals that he will also punish Cadmus. The end of the play shows how the wrath

of his vengeance has made his superiority clear.

In the second episode (lines 433-518) Dionysus is

brought before Pentheus disguised as an attractive foreign agent of the

cult. The two argue about the

religion and Pentheus realizes that his prisoner is quite clever. The chorus then appeals (lines 519-575)

to Dionysus to come join them in their dithyrambic dance so that he may defend

them and the cult from the attack that Pentheus is waging. Next, Dionysus cunningly persuades

Pentheus to quietly sneak up the mountain and spy on the crazed Maenads, luring

the young prince into a trap (lines 576-861). Then the Maenad chorus erupts into another ode

of ecstasy (lines 862-911) in which they reflect on the stupidity of men, and

their habit of provoking the gods to punish them. This punishment is quickly approaching during the fourth

scene (lines 912-976) and then the fourth stasimon (lines 977-1023), as the Dionysus

and Pentheus approach the maenads (pictured above), and as the chorus becomes

fervent with excitement as the moment of Bacchus’ vengeance comes close. In the fifth episode (lines 1024-1152)

a messenger returns to Thebes and reports that Pentheus was ripped apart by the

maenads, and it was none other then his mother, Agave, who ripped off his

headed and danced with it, thinking it was a lion’s. The final brief choral ode (lines 1153-1164) rejoices at

Dionysus victory. The exodos

(lines 1165-1392) then has Agave return to Thebes and realize that she has in

fact killed her own son. Dionysus

then appears as a deity and reveals that he will also punish Cadmus. The end of the play shows how the wrath

of his vengeance has made his superiority clear.

Themes and Thoughts

Sophism

As

discussed above, the Bacchae is full of suggestions about sophism, or “new

learning” as it sometimes called.

Sophism emerged in the latter half of the 5th century BCE and

was led by scientists, historians and philosophers such as Protagoras and

Gorgias. The movement was

characterized by “attacks on traditional religion, established law and social

custom” (Woodruff-xvii). These

attacks were typically based on the sophist’s notion that many existing

practices and beliefs of society were grounded in irrationality. In this way,

Pentheus could be indicated as a symbol of the sophist movement, because of the

way that he attacked the Dionysian religion because of its unusual nature.

As

discussed above, the Bacchae is full of suggestions about sophism, or “new

learning” as it sometimes called.

Sophism emerged in the latter half of the 5th century BCE and

was led by scientists, historians and philosophers such as Protagoras and

Gorgias. The movement was

characterized by “attacks on traditional religion, established law and social

custom” (Woodruff-xvii). These

attacks were typically based on the sophist’s notion that many existing

practices and beliefs of society were grounded in irrationality. In this way,

Pentheus could be indicated as a symbol of the sophist movement, because of the

way that he attacked the Dionysian religion because of its unusual nature.

Methods

of extending these attacks include persuasive speech that utilizes logic to discount

the claims of such irrational groups as the Bacchae (Dionysus’ worshipers), who

behave in a most unconventional way. The

paradox of this claim is that Pentheus’ resistance against Dionysus and his

unconventional followers is based in nothing more then the fact that he wishes

to maintain control over the women of the city. He is not based in any other rationale then this.

Here

it is almost as if Euripides is suggesting that the sophist’s notion of

rationality is perhaps not very substantive at all. Furthermore, it is Dionysus, disguised as the foreigner who

craftily persuades Pentheus to go up the mountain without an army, a decision

that leads to his death. The way

that Dionysus convinces Pentheus with speech is a technique perhaps more

characteristic of sophists. This

deepens the paradoxical nature of the play. These paradoxes could be identified

as the ways in which Euripides presents a dialogue between what Nietzsche

called the “Apollonian” and “Dionysian” elements of Greek society.

Apollo vs. Dionysus

Nietzsche

(pictured below) believed that Apollonian virtues include human reason,

civilized life, dialogue, science, and dialectics. While Dionysian virtues include human emotion, nature,

music, myth, and imagination (327).

With this in mind Apollo seems to be a clear symbol of the sophist

movement. Dionysus is meanwhile seen as a symbol of disorder, chaos and

wildness, as revealed by the fanatical actions of his followers. In fact it is known that the cult of

Dionysus had perhaps no order, or specific ritual to it. Instead it was focused on passively

allowing the god to affect you as he chose. In all, the goal is that one should lose himself with Dionysus.

However,

it is clear that these conflicting elements of Greek life clearly have been

woven together in the Bacchae. Apollonian and Dionysian elements are

blended together in Pentheus and in Dionysus as well. Consider Pentheus who lost his life when he allowed himself

to be driven mad by Dionysus. A

true sophist would discount the god’s ability to influence them so drastically

because it is irrational. If

Pentheus had maintained his order and discipline he could perhaps have escaped

his terrible fate. On the other

hand, as discussed above, Dionysus is forced to resort to some Apollonian

techniques in order to vanquish his foes.

Apart from the fact that he uses persuasive speech, consider that the

Maenads of the chorus provide the basic structure of the tragedy through their

odes. That the chorus is not a

group of citizens from Thebes, perhaps says something about the structure that

the seemingly unrestricted cult members actually hold. This fits with

Nietzsche’s claim that elements of each god’s holdings come together.

However,

it is clear that these conflicting elements of Greek life clearly have been

woven together in the Bacchae. Apollonian and Dionysian elements are

blended together in Pentheus and in Dionysus as well. Consider Pentheus who lost his life when he allowed himself

to be driven mad by Dionysus. A

true sophist would discount the god’s ability to influence them so drastically

because it is irrational. If

Pentheus had maintained his order and discipline he could perhaps have escaped

his terrible fate. On the other

hand, as discussed above, Dionysus is forced to resort to some Apollonian

techniques in order to vanquish his foes.

Apart from the fact that he uses persuasive speech, consider that the

Maenads of the chorus provide the basic structure of the tragedy through their

odes. That the chorus is not a

group of citizens from Thebes, perhaps says something about the structure that

the seemingly unrestricted cult members actually hold. This fits with

Nietzsche’s claim that elements of each god’s holdings come together.

At

any rate, it is clear that Euripides Bacchae poses more questions than it does

provide solutions. This is of

course the nature of tragedy: to incite debate, thought and discussion rather

then silence argument. This play

in particular raises some provocative questions.

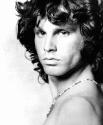

Consider this modern day examples of Dionysian

attributes…

Jim Morrison

Jim Morrison

The rock and roller used intoxication for his artistic

inspiration throughout his entire career.

He even attracted an almost cult-like following that was obsessed with

his singing, voice and poetry. His

art caused these fans to lose themselves while at concerts. His intoxication eventually led to his

death.

Bibiliography

Bather A.G. The Problem of the Bacchae. Journal of Hellenic Studies. Vol. 14. 1894.

Euripides. Bacchae. Ed. with an introduction by

Paul Woodruff. Hackett Publishing, Indianapolis: 1998.

Euripides.

Bacchae. Ten Greek Plays. Ed. with an introduction by L.R. Lind. Houghton Miflin,

Boston: 1957.

Silk, M.S. and Stern, J.P. Nietzsche on Tragedy. Journal of

Modern History. Vol. 55. March, 1983.