"Allegory" in Homer

With "plot" we found that there are several elements, all of which

can be referred to as "plot," which means one should be careful to

understand what is meant:

- a bunch of events,

- a sequencing of those eventsin time

- a causal sequencing of those events

- a more specific causal sequence of events: a complication of

a situation, a climax of that complication, and a resolution

The following is probably not referred to as "plot" but is an

aspect of it

- order of exposition vs. temporal order

- often the events are presented in the order in which they

occurred

- sometimes that order is changed up

- parallel events are told

- flashbacks

- flash-forwards

But that was last time: this time, let's talk about the following:

- What's the difference, if any, between

"allegory," "metaphor," and "analogy"

Mike Dawson, in

https://slate.com/culture/2016/05/an-allegory-is-not-the-same-as-a-metaphor-in-praise-of-the-medieval-literary-tradition.html

Cover of a book:

https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/narrative-and-metaphor-in-the-law/9A11F94DAE675D7FA359846185273A61

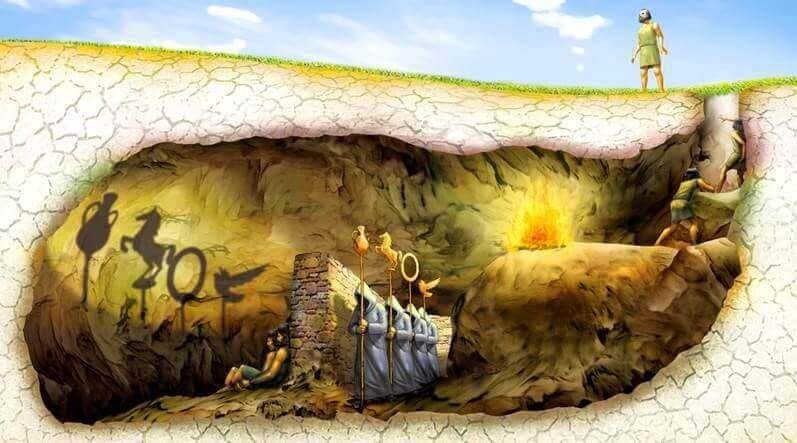

https://www.google.com/search?q=analogy+image+cave&client=firefox-b-1-d&sxsrf=APq-WBv1SWLiCilxLbsXnBzt0xTv3jOXgg:1645013330014&source=lnms&tbm=isch&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwiolr6ZmIT2AhXhj4kEHbrdCDsQ_AUoAXoECAEQAw&biw=1130&bih=574&dpr=2.22

https://www.studiobinder.com/blog/platos-allegory-of-the-cave/

The following are the components I can think of that make up what we

call metaphors, similes, analogies, allegories, and several other

figures of speech:

- putting two different things together

- equating two things that are different

- claiming a similarity between two things that are different

- scope of application:

- how is it focused in terms of what it refers to?

- remember there are two things: it can be focused in some

way on either thing

- focused on one thing? applicable to the the whole world?

Some range in between?

- how is it focused in terms of the story

- is it only applicable for an instant?

- does it permeate the whole story?

- a surface meaning v. a disguised/secret/hidden/real/discovered

meaning

Questions that occur to me:

- can the range of application be expanded beyond what is

explicitly mentioned? How far?

- how does the intention of the creator matter vs. how others

view it?

- what use is it put to: aesthetic? moral? argument?

teaching/illustrating?

In the end, this bunch of terms used in different ways by

different people is a perfect illustration of why certain people,

like me, keep harping on the fundamental importance of defining or

at least understanding one's terms at the start of anything if you

want it to be clear.

- What is "allegory"?

- There is a very good argument that "allegory" should be used

only for things like the book Pilgrim's Progress and

other works that are allegorical in the sense that they are

created as and intended to be read as allegories and are

typically obviously allegorical.

- These allegories rub your nose in the idea that things are

not what they seem: a story about how the character Folly

stumbled through life with her sister Intelligence and her

mother Perseverance and her father Lazybones is that kind of

allegory: it wears on its face the fact that you are

supposed to read it as standing for something else.

- typically, the allegory permeates the whole story

- and the surfaces story is pretty much beside the point,

not the message being conveyed

- One common meaning of 'allegory' is a little bit different

from that: it involves any story in which the surface

meaning of a text differs from another meaning that is also

somehow present in the text, and that other meaning is the

'real' meaning, the 'true' meaning, or perhaps merely "read

into" the text for some purpose.

- Whether or not that looser meaning is your meaning of

"allegory," it's the one used here.

- The Odyssey has been seen as an allegory for every

person's journey through life.

- The Iliad has been seen as an allegory for the

same thing: we are all like Achilles, faced with a choice

between safety and risk, or perhaps between following our

passion and following our cooler more reasonable self.

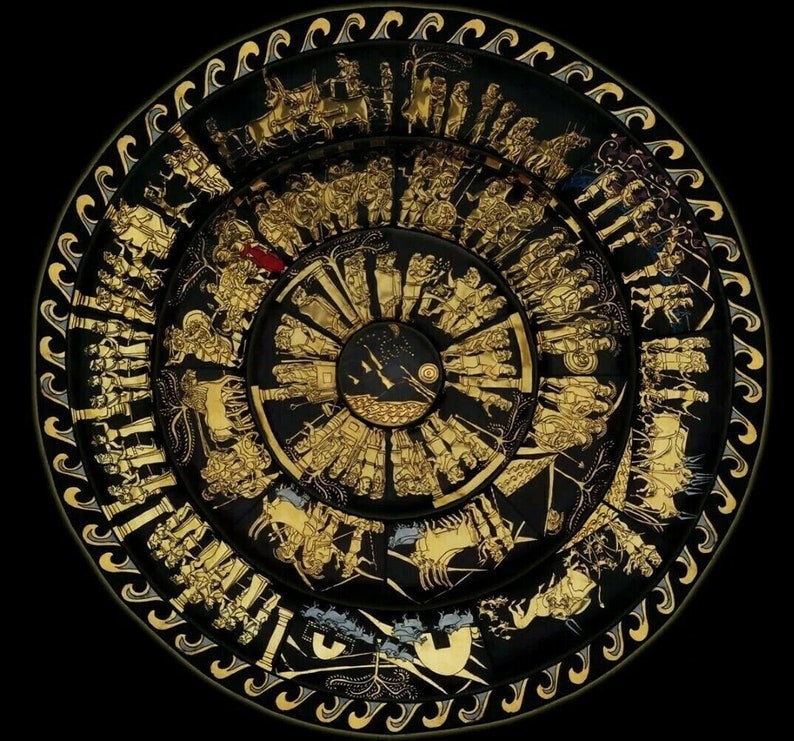

- The shield of Achilles is often seen as an allegory of the

whole Homeric Society: it is the go-to place for

finding societal things in peace time.

- Nowhere in Homer does it say that Odysseus is an allegory

for every person, or that the Iliad is, or that the

shield of Achilles illustrates all of society.

- Note how Cavafy's poem "Ithaki" used "Ithaca" as a

life-destination of some sort: that was an allegorical

reading of the Odyssey: arguably, it had to ignore

many things in the Odyssey and so is not "true" to

the Odyssey, but it is also arguable that it reached

deeper truths by doing so.

- Sometimes the author of a text intends the allegory:

- When Phoinix talks (Iliad 9.500ff.) about "Prayers"

and "Blindness" and urges Achilles to control his anger,

that is allegory, 1) because it uses characters called

"Prayers" and "Blindness," but also 2) because although

Phoinix seems to be talking about characters called

"Prayers" and another character called "Blindness" that roam

around and do things, he is really saying that if

Achilles rejects the embassy, divine retribution may fall

upon him.

- For Prayers are the daughters of great Zeus, halting

and wrinkled and of eyes askance, and they are ever

mindful to follow in the steps of Sin. [505] Howbeit Sin

is strong and fleet of foot, wherefore she far

out-runneth them all, and goeth before them over the

face of all the earth making men to fall, and Prayers

follow after, seeking to heal the hurt. Now whoso

revereth the daughters of Zeus when they draw nigh, him

they greatly bless, and hear him, when he prayeth; [510]

but if a man denieth them and stubbornly refuseth, then

they go their way and make prayer to Zeus, son of

Cronos, that Até may follow after such a one to the end

that he may fall and pay full atonement. Nay, Achilles,

see thou too that reverence attend upon the daughters of

Zeus, even such as bendeth the hearts of all men that

are upright.

- That particular allegory is presented in such a way that

we must conclude that the character Phoinix intends

what he says to be allegorical, and hence the bards were

aware of that too as they sang the poem and put those words

into it.

- So we at least know that allegory in the stricter sense

identified above was in the bards' toolkit: it occurs

once, quite explicitly.

- But does that justify reading other parts as allegory

that are not so clearly meant as allegory?

- Well, first off, all of the "allegorical" readings we

are talking about are different from Phoenix' little

speech

- Phoenix talked of Prayers and Sin as characters: that

is transparently allegorical and gives itself away

- the readings we are talking about involve first

translating the names into what they "really" are

(Athena >> Wisdom, Odysseus >> Everyhuman,

etc.)

- SO the "allegory" that the bards used was very rare, and

it was different

- Let's call what we're talking about "allegorizing": it

takes a text and does some work on it, transforms it into

something with a point, a message

- Is doing that 'presentist' (applying anachronistic ideas

to a text?), whether it is done by an ancient Greek or us?

- Is it just another way to read?

- What legitimacy does it have?

- Sometimes a text is 'allegorized' after the fact.

- That is, in my opinion, the case with all allegorical

readings of Homer aside from a very few instances of

allegory within the text, like the allegory in Phoinix's

words above.

- That does not make the allegory wrong. It just means it is

different from one that the author is putting in there

intentionally as an allegory.

- Later, but still ancient, Greeks allegorized various

elements of Homer:

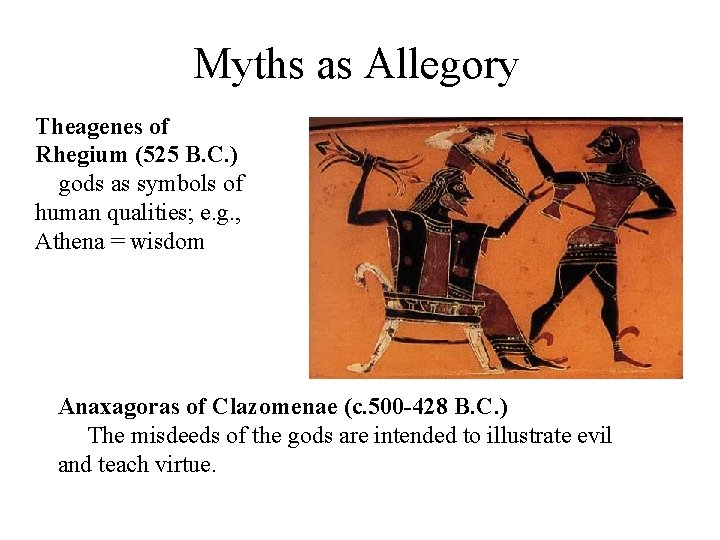

- Theagenes of Rhegium (6th c. BCE, so very early)

interpreted Iliad 21, when the gods fight

against each other, as a conflict of physical "elements"

(hot and cold, dry and wet, etc.).

- so it was a chemical/physics allegory! kinda...cool?

-

- https://slidetodoc.com/ways-of-interpreting-myth-the-web-of-myth/

- this is an attempt to 'purify' myth

- it might even be called "co-opting" myth: taking it

for one's own in a way not true to myth's origins

- Pherecydes of Syros (earliest prose writer, 6th c. bce)

interpreted Zeus' talk of the golden chain by which he hung

Hera by her feet once as allegorical for the structure of

the universe!

- Whether or not any Homeric rhapsode was aware of such a

potential meaning (I think they likely were not, or at

least not concerned with them),

- Why did those Greek do this?

- ...those readings are interesting historically in many

ways. They are trying to connect the burgeoning

proto-scientific efforts of the Greek with their myths and

broader cultural understanding of the world: here is an

impressive bit of ancient Greek pure science:

Eratosthenes' method of measuring the circumference of the

earth (he got VERY close): what these allegorizing

readings were doing was to try to keep the science AND

Homer, even though Homer was, on the surface, at the

veryleast unconcerned with science, and at worst

incompatible with it,

- Public Domain, <a

href="https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=877028">Link</a>

- Plato and Xenophanes were uncomfortable with the

immorality of the gods and so they interpreted immoral

divine acts as allegorical (when Kronos castrates Ouranos,

for instance, or when Ares and Aphrodite commit adultery and

are caught) or rejected the stories altogether.

- Xenophon, a Socratic and a historian of the Classical

period (5th c. BCE) writes that Odysseus is spared because

he did not indulge his appetites to excess as his companions

did: a moral allegory? perhaps not an allegory but merely an

application of a moral onto the story.

- Xenophon's reading is tendentious and selective: it

ignores that Odysseus did indulge his appetites with

Kalypso, with the Sirens, etc. We might counter Xenophon's

reading and say that Odysseus just got lucky?

- These ancient efforts are very short, just suggestions, a

few sentences, not full-fledged retellings.

- This has been a far from complete tour of "allegorical"

efforts to deal with Homer.

- We have no explicit evidence that the bards tried to put

'allegorical' or 'hidden' meanings into their poems, or

thought about it

- But starting in the archaic age, we find more and more

efforts to read Homer as having some sort of privileged

meaning below the surface level of the story.

- This continues all the way up to our time.

- In modern times, the only allegorical readings that I have

found taken seriously as helpful interpretations of the poem

rather than allegorizations perpetrated by particular

individuals are the idea of Odysseus as every human, the

choice of Achilles as a generic human plight, and the idea of

the shield of Achilles as a microcosmic representation of the

whole world.

- That does not mean that allegorizations are in any way

inferior readings.

- It means they are less informative about the bards and the

creation of these poems

- The allegorizations are more informative about the times

when the allegorizations occurred and how Homer was received

then.

- That is part of "reception history" a big field of

literary/cultural/intellectual studies particularly in

Classics

- Buy it now: "genuine ancient greek Achilles' shield":

- https://www.etsy.com/listing/1116787579/genuine-ancient-greek-achilles-shield-36?gpla=1&gao=1&&utm_source=google&utm_medium=cpc&utm_campaign=shopping_us_a-accessories-costume_accessories-costume_weapons&utm_custom1=_k_Cj0KCQiA3rKQBhCNARIsACUEW_bGdAM2OzD5lI6fQB99EBdP9QEdmM-eyrXLLqyiM-D0ZgNXLKuuiHgaApe0EALw_wcB_k_&utm_content=go_1844702565_65111515330_346428849815_aud-301856855918:pla-353036817099_c__1116787579_529097145&utm_custom2=1844702565&gclid=Cj0KCQiA3rKQBhCNARIsACUEW_bGdAM2OzD5lI6fQB99EBdP9QEdmM-eyrXLLqyiM-D0ZgNXLKuuiHgaApe0EALw_wcB

-

-

-

The Arming of Achilles, Archaic Greek Black-figure Neck Amphora

by the Camtar Painter, ca. 550 BCE.from Boston Museum of Fine

Art

- https://theshieldofachilles.net/2018/08/14/thetis-delivering-achilles-shield-in-art-through-the-ages/sc251462-2/

- link to MFA: https://collections.mfa.org/objects/153416?image=4

- In general, why allegorize Homer?

- In ancient times:

- Because one is shocked by Homer and wants to save the text

from being outrageous.

- Or because one has a pet theory, Homer is a renowned

foundational cultural authority, and so one wants to find

support in Homer, to claim Homer is on one's side.

- Because one thinks that previous thinkers, starting with

Homer, were on the right path but didn't quite get things

right or clear: this may not be allegory: it may be just

part of the history of ideas, or an instance of "progress."

- Or maybe one wants to claim Homer as a predecessor for

reasons that have little to do with whether or not Homer

ever even imagined what you say is there.

- Because one thinks that mythology is a revelation of truth

that requires laborious interpretation to discover its

hidden truths (many say stoics thought that, but a more

careful reading of the stoics would reject that in favor of

a much more interesting an nuanced view that we don't have

time for, unfortunately).

- Because one wants to show that Homer contains worlds, is

all-purpose, and anticipated all later intellectual

developments (i.e. Homer is one's foundational text and so

one must defend Homer wherever people claim he is lacking:

sort of like people who claim that Genesis really just tells

the story of evolution).

- This is akin to the rather common phenomenon of "Golden

Age" attitudes:such attitudes think there was a golden age

in the past: the past was better, superior, and if we

could just get back to that golden age, all would be well.

- In modern times:

- Shield of Achilles: it is a huge episode, and one wants a

reason for that. If it is mean to represent the world order

and human's place within it, that would be a fitting reason.

And that Achilles, the hero who is facing two options for

how he should fit into the human world, get the shield is

also fitting.

- It is an artistic reason

- Another reason, one that is not at all incompatible with

that, is that the "Shield of Achilles" was a separate

song, or separable episode, in the bardic toolbox, and

whoever stitched together Iliad shoehorned it in

where it is.

- Odysseus as every human: why that allegory? is it that one

wants to explain the appeal of the poem across ages?

one thinks that it fits into a much larger pattern that pops

up all over in human culture (hero's journey)? one wants to

compare visions of what it means to be human, and thinks

that there must be one in Odyssey, and Odysseus

represents it?

- Is it sufficient as a representation of all humans?

- compare Lord of the Rings: many people see those

hobbits as Christian heroes, namely as humans caught in a

world full of forces greater than themselves, bumbling

through among forces beyond their control, and yet having to

deal with that world as best they can, and triumphing.

Others think that the one ring is allegory for nuclear

weapons. But Tolkien himself, the author, rejected

allegorizing his work! Does it matter what he thought?

- Contrast that with George Orwell's Animal Farm,

which is clearly allegorical in intent, albeit one must

first 'allegorize' it by identifying what the various

animals stand for. Less so, Lord of the Flies is

allegorical. Are all texts somehow allegorical? or at least

allegorizable?

Dr. Seuss' 'sneetches'