Marble bust of Homer: a Roman copy of a Hellenistic

statue that is lost.

Originally from en.wikipedia; description page is/was here..

Original uploader was JW1805 at en.wikipedia, Public Domain,

https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=2171360

Newbies to the class: Brightspace is used only for submission of

written material and grading. There is an announcement on

Brightspace that has the address of this website, which is

the course website. We will use this website for the syllabus,

notes, and many other things. We will also use teams for

discussion and for those who are forced to go remote for a time.

Today, the plan is to talk about Iliad 1: please write down a

question or an observation you have about Iliad 1 NOW.

By William-Adolphe Bouguereau, Public Domain,

https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=70926

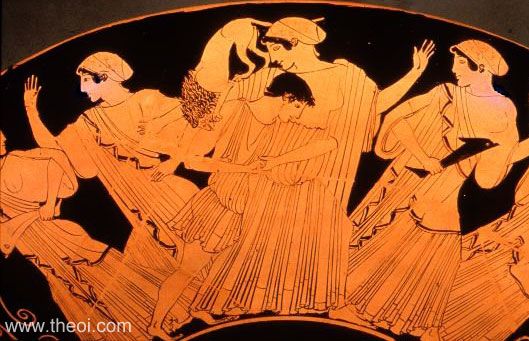

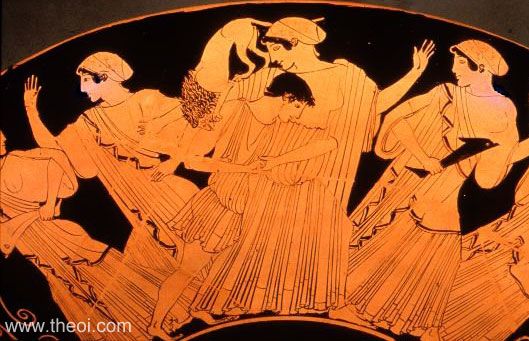

Achilles tending the wounded Patroclus

(Attic red-figure kylix, c.

500 BC)

By Sosias (potter, signed). Painting attributed to the Sosias

Painter (name piece for Beazley, overriding attribution) or the

Kleophrades Painter (Robertson) or Euthymides (Ohly-Dumm) -

User:Bibi Saint-Pol, own work, 2008, Public Domain,

https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=3574713

Some notes about Iliad 1

As the class goes on, I will stop doing this sort of commentary, but

for now, I want to concentrate on the text. Soon, we'll learn more

about orality, what archaeology can offer us, Homeric ethics, etc.

Several people asked in their daily comment last time about how

to read and study in this class. Here's a suggestion. In your

life, you may read some of these texts only in this class, and if

you are too rushed for time, you will only read them once (not a

good idea) even in this class. Here's what I would tell you: find

a couple things you are interested in early on, and make

notes in the text (underlining, high-lighting, marginal comments)

and keep lists of passages that touch on

those issues. Maybe you want to keep a running summary of the plot

and your thoughts about that! A great idea and so much better than

Sparknotes, etc. because you made it, which means you were

actively learning. That is what knowing and understanding often is:

you yourself finding a thread, following it, identifying where it

appears, thinking about it, and coming up with ideas about it, then

repeating all that to make sure your idea stands up. You can do this

and should start keeping a few lists or

running commentaries NOW. This is a skill, a

technique, that can help you in all sorts of ways in all sorts of

places (in any job, in doing your taxes, in hobbies, etc.). It's

kind of an alternative/parallel to keeping a diary.

I mistakenly told you that Wilson's translation kept the original

Greek line numbering: it is clearly not quite straightforwardly true

of her Iliad. Translating involves making an infinite number

of choices, some wittingly, some unwittingly. So there are two sets

of line numbers in Wilson's text: the ones on the right in black and

the ones on the let in a grayscale shade: the grayscale numbers are

the lines of the Greek text!). That is a very good solution to a

translator's problem, and one you will not find as well done in

other texts.

You should follow along with the English (on screen or in your book)

and note where you cannot find what I am talking about at the right

line number: I will be talking about the Greek text's line numbers

and using mostly my own much more literal translations.

- Line 1

- Sing! the whole of Iliad and Odyssey

is a song! to be performed! to the Kithara!

(a stringed instrument)

- goddess: the 'goddess' is the muse,

the source of poetic inspiration, and hence, the singer, thru

the bard! The Greeks take this much much more literally and

seriously than I, an atheist in a largely monotheistic and

pluralistic society.

- Peleus' son: ancestry determines

nobility: if you don't have noble ancestry, YOU ARE NOT NOBLE

- it is also sufficient for nobility: you can be a

dirty rotten scoundrel, but if you have noble ancestry, YOU

ARE THEREFORE NOBLE, a 'hero.'

- wealth can play a similar role

- in the US, we have a very strong mythology that rejects

'blood' as a determiner of worth and quality, but it is

not strong enough: blood, actually DNA, still matters a

great deal. We now call this a type of privilege.

-

A 5th c. red-figure vase painting in the Munich

Antikensammulung, attributed to Douris

- Achilles: the best fighter in the war, the greatest Achaian

warrior

- Lines 1-15 Agamemnon is 'Atreus' son' and Apollo is 'Son of

Zeus and Leto': sometimes they have other epithets.

- epithets are monikers, ways to refer to

people. Sometimes they accompany the name, as in "swift-footed

Achilles" or "rosy-fingered Dawn" (the rising sun): they are

tremendously frequent in the epics.

- They are a key feature of oral poetry and one of the ways

the Milman Parry and Albert Lord and others confirmed that

these epics are in fact oral poems, not written poems.

- Wilson chose to 'translate' these names as Agamemnon and

Apollo: the Greek has only 'Atreus' son' and 'Son of Zeus and

Leto': what difference does that make?

- Line 2

- Achaians: one of three names for "the Greeks": "Greeks" is

NOT one of those three: "Greeks" is a later name: the three

names are "Achaians" (frequently spelled Achaeans:

Achaea is a land in the northern Peloponnese), "Argives"

(from Argos, a city on the Peloponnese), and "Danaans."

- Another word for Greeks, "Hellenes," which is the

adjective form of what has become the modern name of Greece,

Hellas, is used ONCE in Iliad.!

- The Hittite name Ahhiyawa, which in Hittite refers

to a land to the west of the Hittite empire, may refer to

historical Mycenaeans: we have this name on a few Hittite

clay tablets in cuneiform script.

- Wilson chose to translate the 'Achaeans' as Greeks: what

difference does that make: it gives the impression that

there was a notion of "Greece" as a nation that is

continuous with Greece the nation: there is, but it is more

complex than that.

- Line 3

- Hades: the underworld god as well as his realm: Hades is

Zeus' brother. Zeus' other brother is Poseidon, god of the

sea.

- Line 7

- 'Atreus' son the lord of men: Wilson says Agamemnon: note

that his lineage is enough to identify him: also note that

"lord of men" is an epithet

- many people are identified merely by their parentage in

Homer

- LIne 9-... Why Achilles is mad

- Line 9-11

- Apollo, a significant Olympian god (there were 12

Olympians), whose human priest is Chryses.

- 16

- 'Atreus' two sons': we have met Agamemnon, but Atreus' other

son is Menelaus, Agamemnon's brother, a fellow king,

and Helen's husband, the one whose wife went to Troy

with Paris/Alexander and thus set off the chain

of events that led to war

- 14 and 21

- Apollo has an epithet "who strikes from afar": he is

often depicted with a bow. The bow is literal, but also

figurative (he can hit them with a plague).

- 20

- kidnapping and ransom seems to have been a normal thing, not

unusual, a fine acceptable way for a hero to go out and make a

living (if you are a noble male, or among the underlings of a

noble male, of course): probably reflects historical reality

in Archaic and earlier Greece: think of "going viking."

- when you go out raiding or on campaign, there is always a

concern about whether you will return home, and

whether you will return with plunder (glory and honor)

or not

- the Odyssey is all about one man's return home.

Greek for return is nostos and hence we have the

English word 'nostalgia' (pain/desire to return)

- 22

- "All the rest of the Achaians kept quiet": like a Hollywood

movie, there are only a few speaking roles in Iliad,

but many crowd scenes

- pay attention to the crowd (perhaps make a list, or start

underlining and put a symbol in the margin), i.e. the whole

army: the fighting is actually as much about large army

movements as individual combat, but it doesn't appear that way

most of the time at first glance

- note that the crowd, the army, large groups, are only

present in short lines: the epic spends no time on them, but

they are there.

- 30's

- the god's staff and ribbons: symbols of the god, and humans

are supposed to respect them

- note that this sort of tradition is what functions as the

"law" of the Iliad: there is NO written law: only

traditions, strong ones.

- there are traditions about how to treat a messenger, or a

traveling stranger, or a host, etc.

- Paris violated such a tradition by taking Helen with him

(note that in the epic, her role is often elided, not really

explained: did she run, was she seduced, or did she seduce,

was she taken? etc.).

- 30's

- Chryseis: what is she (or any woman in general) good for?

- from what Agamemnon says here, working a loom and being in

bed with a man

- don't underestimate the loom: it took hundreds of hours of

work to make each article of clothing: years to make a sail:

we take for granted the processing, the spinning, the

weaving, and the sewing, because we have machines. This was

incredibly important and sophisticated work. Computers in

fact have their origin in weaving: it's that complex and

technical.

- Perhaps taking the women (the men were killed mostly,

apparently) really is as much about labor as it is about

anything.

- as for sex, relationships that involve it, sexuality,

gender issues, etc., pay attention to them: they are not

discussed much in the epics, never explicitly, but they are

incredibly important and interesting, and the occasional

line adds to the picture: if you are interested, start

keeping a list now, as you read, of passages the

mention such things.

- 39 ff

- Chryses calls down the wrath of Apollo, whose arrows are a

plague, a sickness, in the Achaian camp. Note the prayer

formula: "If every I did something for you, god, now do

something for me": it is called "do ut des"

(Latin for "I give so you give") and is a very strong and

widespread religious idea: prayer and religion as bargaining

with a higher power:

- it is also an extremely simplistic religious formula

rejected and ridiculous from more sophisticated religious

points of view. But it works, apparently, in this epic

world. Most all of the rituals and sacrifices and prayers in

the epic word are do ut des

- in fact, most of the religion we hear about on a regular

basis, sacrifice, votive offerings, in historical Greece is

still do ut des

- note that there was, as far as we can tell, no good medical

knowledge whatsoever, no scientific method, no controlled

trials, etc.: the physical basis for contagion, cleanliness,

medicine, all were utterly misunderstood. Nonetheless there

were 'doctors' (Machaon is the doctor on the

Greek side, but he is not mentioned until much later in the Iliad)

and they did more good than harm.

- 53 (73 in Wilson)

- nine days: note the occasional quick mention of time

passing: if you add up all the time that is reported as part

of the actual action of Iliad (not flashbacks or

recountings of the past, or flash forwards or references to

what will happen), it is about 50 days! If you are interested,

keep a list as you read.

- 55

- Hera inspires Achilles to call an assembly: note

that Achilles' thought is caused by Hera!

Gods not only interact with humans as actors: they also

inspire humans' thoughts! or maybe such things are just

attributed to the gods?

- Hera has pity on the Achaians: does that mean she is on

their side? Here she is helping them, certainly. Watch for

things like this: this is the evidence for whose side a god is

on and why. Evidence is important! keep a list of

who's on which side?

- So far, Hera helps the Achaians and Apollo helps Chryses

against the Achaians.

- Note that Athena will soon descend and hold back Achilles,

physically and in person, appearing to him alone: gods work in

various ways. What are they? Personified motivations? Aspects

of one's personality (Athena is wisdom, Aphrodite is lust,

etc.?)

- 64

- Achilles apparently knows that Apollo is causing the plague:

how does he know?

- because Apollo's sphere of power includes such things as

plagues, and so it must he Apollo: that is background

cultural knowledge that the audience would have. You'll

slowly build your own such knowledge: it is a small part of

why re-reading is so rewarding.

- what we know is that Achilles says the plague is caused by

Apollo: can we ask, does Achilles have his own not so

obvious agenda? why might Achilles use Apollo as a

rhetorical pawn in his own agenda?

- Why shouldn't we ask that? It depends on how you think

Homer should be interpreted: is the text driven by a

straightforward reliable narrator or does he work with

not-quite said motivations? Do the characters shoot

straight or can we attribute motives and machinations to

them?

- Maybe what we learn in lines 75-85 explains it: maybe

Achilles talked to Kalchas and they have this all planned

out beforehand as a strategic move relative to Agamemnon. So

it's the politics of the Achaean army:

- How would we support that interpretation? Because

Achilles mentions it here before Kalchas says it! He has

knowledge of what Kalchas is going to say: how if not by

having talked to him?

- 75-85

- Kalchas, a seer and priest of Apollo who watches

birds in flight and thus predicts the future, asks Achilles to

protect him, because what he will reveal (that Agamemnon's

actions are why Apollo has rained this plague down upon the

Achaians) will anger Agamemnon

- was this all planned out beforehand as some sort of

manipulative rhetoric to get the Achaians to go home?

- or to damage Agamemnon's reputation and status?

- or is Achilles wanting to usurp Agamemnon's role as

leader?

- are we even right to think of such things? the poet, after

all, gives us little direct explicit evidence that that is

the case!

- I think it is a good idea to pursue all interpretations,

with certain warnings and with our eyes wide open as to what

we are doing.

- but not as if any one interpretation is the best or the

only way to read the text

- I am honestly not suggesting that such an interpretation

is right or wrong, but merely trying to point out that if

you engage in such an interpretation, the nature of your

evidence becomes indirect. If your interpretation is

coherent and interesting, I think it is a good one, even if

it contradicts other viable interpretations. Literature is

not necessarily unambiguous or free from contradiction, and

often more than one interpretation is possible and that can

help make the literature stand the test of time, because

that can make it interesting and about important issues. It

can also make it relevant in very different ways in

different times.

- Also, maybe by doing this, we ourselves are

re-interpreting the myth behind the epic and re-formulating

it to suit our own psychology and interests: nothing wrong

with that. But do it with your eyes wide open as to what you

are doing.

- We can pooh-pooh divination, and I do, but in antiquity, it

was held to be a science, an organized field of

expertise, and to have roots in divine placement of clues and

signs in the world. Thus it can tell us what an intellectual

skill, a science, looked like to them at the time.

- think about the idea that signs are all around us, about

human lives, in the actions of birds, the entrails of

animals, etc.

- think about how that world would work, if it were really

true: how would those signs get there? why would they be

there? how would/could interpreting them be clear and

unambiguous?

- wow: now go write a brilliant piece of fiction that

incorporates the system you have built up in answer to the

previous two bullet points: seriously, it could be a

wonderful thing!

- or create a game with mechanics that call on that world!

- He says Agamemnon has to give the woman Chryseis back. Note

that 9 years before this time, Kalchas told Agamemnon he

had to sacrifice Iphigenia, Agamemnon's

daughter, in order to get fair winds to get to Troy, and

Iphigenia was sacrificed! That's part of why Ag. is so bitter

at him. BUT THAT IS BARELY ALLUDED TO HERE; the

audience would have been keenly aware of it in ancient Greece.

Is that a good reason to think that Homer's text works with a

subtext that the audience would have been aware of and that

the singer knew the audience would have been aware of? Yes it

is.

- 101-120

- Agamemnon's speech

- he rails against Kalchas, because Kalchas has never once

said anything that Agamemnon liked (remember Iphigeneia)!

Does this mean Kalchas is plotting and machinating against

Agamemnon? or does it simply mean that in fact Agamemnon is

annoyed with Kalchas, because Kalchas is merely reporting

the fact that Agamemnon's actions are the root of the

problem: giving Chryseis back to her father Chryses, this

time without a ransom, will solve the problem? Different

interpretations.

- Agamemnon, interestingly, likes Chryseis, his plunder,

more than his own wife!!! (Wilson line 152) If you know

later events (and the audience does), you know that

Agamemnon will bring home another woman war captive,

Cassandra, and that Agamemnon's wife Clytaemnestra, will

kill Agamemnon partly because he prefers others to her and

partly because he sacrificed their daughter Iphigeneia.

Soap-oper-epic!

- But also, it tells you about norms of the time. Are

there 'functional analogues' to all these things in modern

times? Women as acquisitions? Trading women? Sacrificing

daughters? Hiding behind lawyers and policy? Maybe not

straightforwardly equivalent, but maybe not so entirely

different in essence?

- The epics, and myth in general, and literature in

general, is full of "echoes" and "parallels": keep a

list of them?

- Why does Agamemnon suggest that he needs another prize?

(Wilson ~158) does he know that they are machinating against

him and so is he making a counter-move directly against

Achilles and his co-machinators? or is he simply pointing

out that the heroic code requires that he have honor,

that Chryseis IS honor, and so if he loses her, he

should get another honor?

- Note, if you have not already, that Chryseis' point of

view is not related. She is spoil of war. Spoils are part

of the heroic code. Once in a while Homer seems to

question it, but is that real questioning or merely

dramatic coloring? The playwright Euripides will certainly

question it when we get to his works.

- Note, for instance that much later, when we hear about

Achilles' own spoil of war, the woman Bryseis, that when

they came to take her "she went unwillingly": that's all

that is said, but why say that she went 'unwillingly'?

What does it mean? What does it tell you?

- 125 in Achilles' speech: (Wilson 160's)

- distribution of spoils: a very important part of

the heroic code: you raid and take spoils, then divide

them. The spoils ARE your honor, just as your money IS your

worth according to many today.

- Achilles suggests a perhaps reasonable alternative:

there are no unclaimed honors lying around for Agamemnon,

so he should get a promissory note: 3-4 times the value of

Chryseis next time there is a distribution

- seems reasonable, and might undermine the interpretation

that holds that there are undercurrents here of

machinations and power-maneuvers. Maybe those who

interpret it that way are simply too blinded by their own

world and their own world view to understand the epic one?

Maybe promises like that are worth nowhere near as much to

him as a woman in his tent. Hmmm.

- Note the line 'We have looted from the neighboring

towns' which Lombardo translates as "Every town in the

area has been sacked": how do you think you supply

your army when you are attacking a town far across the sea

for 9 years? This has been one non-stop years-long

plunderation of everywhere that was not an ally.

- 130-150's

- Agamemnon's speech

- He comes across as a selfish and bad leader, right? Is he?

- The scene seems to me like a pack of wolves who have a

carcass: a bird comes along and flies off with

one's choice morsel from the carcass, so he goes over to

another wolf and tries to take its morsel.

- And Agamemnon is like a child who does not understand

delayed gratification.

- Is that fair? Is it an inaccurate representation of how

things like international relations work, for instance?

- Agamemnon is just wielding supreme power over his army and

not brooking protest. It's military, after all. It's not

diplomacy or subtle court politics.

- But Agamemnon agrees to give back Chryseis.

- 155-ish

- Achilles' speech

- WOW!!!!

- Truth to power? or maybe 'aspirant to greater power to

power' or maybe "really skilled underling to the person with

power" or maybe 'tragically trapped human raging against the

trap that is his life?'

- Achilles' analysis of the situation is intense! and seems

sensible.

- and he is going to abandon the allied host.

- Note the mini-list of other leaders: lists are

frequent. How would that help an oral poet?

- 183-ish

- Agamemnon's reply

- Lombardo's translation, excerpted "Go ahead and

desert...If you're all that strong, it's just a gift from

some god...I couldn't care less about you...you will see

just how much Stronger I am than you, and the next person

will wince At the thought of opposing me as an equal"

- Agamemnon's power relies on being maintained, on

appearances

- He insults physical strength and talks instead of power.

- Physical strength and power were much more closely

linked in antiquity, but still they were entirely

different.

- Note how some highly intelligent, thoughtful, and

capable leader in our nation asked Pete Hegseth how many

pushups he could do in the hearings yesterday!

- 190's to 210's

- Athena, sent by Hera, persuades Achilles not to (try to)

kill Agamemnon.

- Only he can see her!

- Achilles' reason for listening to and obeying Athena?

"Obey the gods and they hear you when you pray."! that and

the promise of 4-fold spoils (i.e. Achilles knows about

delayed gratification)

- This is great evidence for any argument about what the

gods are: if you are interested in such things, keep a

list of such passages with notes.

- 235-ish ff.

- Achilles' speech back to Thetis

- the scepter: symbol of power: pay attention to the things,

like forks and scepters and cups: then when it

comes to archaeology, look for them!

- note that Achilles says that Agamemnon never actually

enters battle himself! remember I said pay attention

to the crowd: even though the Iliad often seems like

mostly one-on-one combat, that is just like in Braveheart,

when Mel Gibson seems like the only warrior the camera pays

attention to, but really the battle is a confrontation of

two masses of men.

- It seems like a narrative ploy as much as a reflection

of any possible 'reality' of how fighting occurred.

- note too how Achilles insults the Achaian rank and file as

"not real men"

- 260's

- Nestor

- the prototypical wise old man: from a previous generation,

wise of counsel.

- Note that he fought alongside Theseus, and so he is of

Heracles' generation (Heracles too sacked Troy, and that

is mentioned in Iliad at 7.451, 20.145 and

21.442!)

- He seems to be a foil for Agamemnon and Achilles'

hotheadedness, a wise man who is not heeded.

- he holds up the right of a scepter holding king over all

others.

- 320's

- first appearances of Patroclus and Odysseus

- Patroclus is Achilles' best friend, second in

command

- many a person ships them or says he actually is

Achilles' lover (but Homer never actually says that:

Aeschylus will put them together as lovers, but that

tragedy has not survived down to our time)

- Odysseus is known as wily and tricky, good at

speaking: he is king of Ithaca, an island on the other side

of Greece toward Italy.

- 330's Agamemnon sends his minions Talthybius and

Eurybates to take Briseis from Achilles

- Achilles is gracious to them: there is a tradition that

heralds are respected and protected

- remember, that is the closest we get to 'law' in the

epics

- Briseis "goes unwillingly": probably meant to glorify

Achilles, but still, interesting that she is given some

personhood and agency, minimal as it is.

- 360's

- Achilles calls on his mother Thetis, a sea

goddess, who laments that her son Achilles will have such a

short life, that of a fighter.

- this theme of a short life of glory versus what?

the boring life of a peaceful noble: that is "Achilles'

choice" and it has a lot to do with the heroic

code

- She agrees to intercede with Zeus for Achilles, but says

that Zeus and the other gods have gone to Ethiopia for

feastings and won't be back for 12 days.

- note what that does for the narrative: Zeus is out of

cell range, and so he is there, in our minds, perhaps

going to do something important, but on hold. A kind of

CPD.

- 378ff

- Achilles repeats the whole story up to now in a shortened

version: what does that do for the oral poet? the aural

audience?

- note that Cilician Thebes

is where Chryseis was captured by Achilles. There are

several places called Thebes: this one is not well known.

It's among the dozens of place names mentioned in the Iliad.

You can't learn them all. Know the most important, the ones

frequently mentioned.

- 429

- Achilles laments for the loss of Briseis: what does that

mean? is he lamenting his loss of honor, or does he have

feelings for her?

- the two are not incompatible: he could do both. But the

Greek, and the English, doesn't make it clear, but maybe it

tilts toward his honor when the narrator says she was "taken

by force from him against his will": back at 390-92, where

Achilles talks about it, is he lamenting that it was forced

or that he lost her?

- It might be important for an interpretation of women's

roles and treatment.

- 445ff

- Odysseus puts in at Chryse and there is a type

scene: a feast.

- There are many and varied type scenes in

these epics: a 'type scene' is a scene that occur in

various guises repeatedly. They are like old friends after a

while.

- remember, no refrigeration: you sacrifice (slaughter) and

you have to eat it soon or preserve it somehow.

- the division of the sacrifice is parallel to the division

of spoils from battle: it is done according to some

principle of fairness that takes social position heavily

into account.

- 493

- 12 days pass

- the gods return from feasting on Ethiopian sacrifice

- 490's ff.

- Thetis goes to Zeus to ask him to do Achilles a favor.

- note that she invokes the formula "if ever before I have

done something for you, do this now for me": do ut

des a prayer formula we've seen before: a

reciprocal exchange idea of relations with gods: also

applies to human relations.

- we learn that perhaps the "will of Zeus" at the

beginning of the book was NOT just fate: it was what Zeus decided

himself based on doing a favor for Achilles (the favor is to

let the Achaians lose for a while until they have to beg

Achilles to come back and thus do him honor)

- we also learn that at least according to Hera, Zeus has

favored the Trojans in the past: he seems here like by far

the most powerful god among powerful gods, not a wise and

just all-powerful ruler here.

- 530's ff

- meeting of gods: another type scene (the

messenger scene with Talthybius and Eurybates going to

Achilles was another type scene: any scene that

follows a fairly predictable pattern that is repeated a few

times is a type scene.

- note first that Hera accuses Zeus of secret counsels and

plots: that perhaps gives us permission ourselves in our

own interpretation to think that maybe some of what is

happening has hidden motives that we are justified in

speculating about (e.g. that Achilles and Kalchas has

planned out the earlier confrontation with Agamemnon, even

if it might not have gone as planned).

- Hephaestus provides a little comic relief, but also makes

Olympus seem like an abusive, dysfunctional human

household/village.