This is the text of an article by Mendelsohn in the October 8, 2018

New Yorker: we will go thru it and I will comment on the

bold-faced items. I believe this is "fair use" for educational use.

Since the end of the first century A.D., people have been playing a

game with a certain book. In this game, you open the book to a

random spot and place your finger on the text; the passage you

select will, it is thought, predict your future. If this sounds

silly, the results suggest otherwise. The first person known to have

played the game was a highborn Roman who was fretting about whether

he’d be chosen to follow his cousin, the emperor Trajan, on the

throne; after opening the book to this passage—

I recognize that he is that king of Rome,

Gray headed, gray bearded,

who will formulate

The laws for the early city . . .

—he was confident that he’d succeed. His name was Hadrian.

Through the centuries, others sought to discover their fates in this

book, from the French novelist Rabelais, in the early sixteenth

century (some of whose characters play the game, too), to the

British king Charles I, who, during the Civil War—which culminated

in the loss of his kingdom and his head—visited an Oxford library

and was alarmed to find that he’d placed his finger on a passage

that concluded, “But let him die before his time, and

lie / Somewhere unburied on a lonely beach.” Two and a

half centuries later, as the Germans marched toward Paris at the

beginning of the First World War, a classicist named David Ansell

Slater, who had once viewed the very volume that Charles had

consulted, found himself scouring the same text, hoping for a

portent of good news.

What was the book, and why was it taken so seriously? The answer

lies in the name of the game: sortes vergilianae. The Latin

noun sortes means lots—as in “drawing lots,” a reference to the

game’s element of chance. The adjective vergilianae, which means

“having to do with Vergilius,” identifies the book: the works of the

Roman poet Publius Vergilius Maro, whom we know as Virgil.

For a long stretch of Western history, few people would have found

it odd to ascribe prophetic power to this collection of Latin verse.

Its author, after all, was the greatest and the most influential

of all Roman poets. A friend and confidant of Augustus, Rome’s

first emperor, Virgil was already considered a classic in his own

lifetime: revered, quoted, imitated, and occasionally parodied

by other writers, taught in schools, and devoured by the general

public. Later generations of Romans considered his works a font

of human knowledge, from rhetoric to ethics to agriculture; by the

Middle Ages, the poet had come to be regarded as a wizard whose

powers included the ability to control Vesuvius’s eruptions and to

cure blindness in sheep.

However fantastical the proportions to which this reverence grew, it

was grounded in a very real achievement represented by one poem in

particular: the Aeneid, a heroic epic in twelve chapters (or

“books”) about the mythic founding of Rome, which some ancient

sources say Augustus commissioned and which was, arguably, the

single most influential literary

work of European civilization for the better part of two

millennia.

Virgil had published other, shorter works before the Aeneid, but

it’s no accident that the epic was a magnet for the fingers of the

great and powerful who played the sortes vergilianae. Its central

themes are leadership, empire, history, and war. In it, an

upstanding Trojan prince named Aeneas, son of Venus, the goddess of

love, flees Troy after its destruction by the Greeks, and, along

with his father, his son, and a band of fellow-survivors, sets out

to establish a new realm across the sea, in Italy, the homeland

that’s been promised to him by divine prophecy. Into that

traditional story Virgil cannily inserted a number of

showstopping glimpses into Rome’s future military and political

triumphs, complete with cameo appearances by

Augustus himself—the implication being that the real-life

empire arose from a god-kissed mythic past.

By <a

href="//commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/User:Till.niermann"

title="User:Till.niermann">Till

Niermann</a> - <span

class="int-own-work"

lang="en">Own work</span>,

Public Domain, <a

href="https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=388210">Link</a>

By <a

href="//commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/User:Till.niermann"

title="User:Till.niermann">Till

Niermann</a> - <span

class="int-own-work"

lang="en">Own work</span>,

Public Domain, <a

href="https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=388210">Link</a>

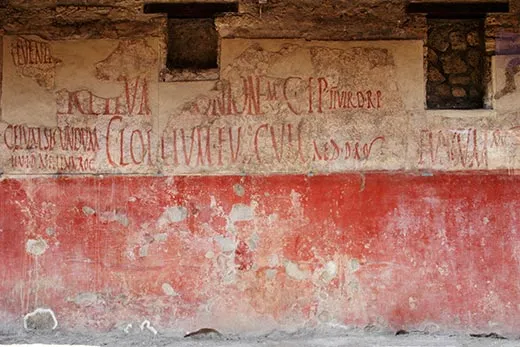

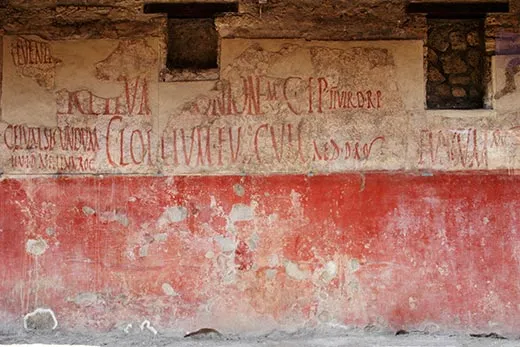

The Emperor and his people alike were hooked: within a century of

its author’s death, in 19 B.C., citizens of Pompeii were scrawling

lines from the epic on the walls of shops and houses.

from:

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/reading-the-writing-on-pompeiis-walls-1969367/

People haven’t stopped quoting it since. From the moment it

appeared, the Aeneid was the paradigmatic classic in Western art and

education; as one scholar has put it, Virgil “occupied the central

place in the literary canon for the whole of Europe for longer than

any other writer.” (After the Western Roman Empire fell, in the

late fifth century A.D., knowledge of Greek—and, hence, intimacy

with Homer’s epics—virtually disappeared from Western Europe for a

thousand years.) Virgil’s poetry has been indispensable to

everyone from his irreverent younger contemporary Ovid, whose

parodies of the older poet’s gravitas can’t disguise a genuine

admiration, to St. Augustine, who, in his

“Confessions,” recalls weeping over the Aeneid, his favorite book

before he discovered the Bible; from Dante, who chooses

Virgil, l’altissimo poeta, “the highest poet,” as his guide through

Hell and Purgatory in the Divine Comedy, to T. S.

Eliot, who returned repeatedly to Virgil in his critical

essays and pronounced the Aeneid “the classic of all Europe.”

And not only Europe. Alexander Hamilton, Thomas Jefferson, and

Benjamin Franklin liked to quote Virgil in their speeches and

letters. The poet’s idealized vision of honest farmers

and shepherds working in rural simplicity was influential,

some scholars believe, in shaping the Founders’ vision of the new

republic as one in which an agricultural majority should hold power.

Throughout the nineteenth century, Virgil was a central fixture of

American grammar-school education; the ability to translate passages

on sight was a standard entrance requirement at many colleges and

universities. John Adams boasted that his son John Quincy had

translated the entire Aeneid. Ellen Emerson wrote her father, Ralph

Waldo, to say that she was covering a hundred and twenty lines a

day; Helen Keller read it in Braille. Today, traces of the

epic’s cultural authority linger on: a quotation from it

greets visitors to the Memorial Hall of the 9/11 Museum, in New

York City.

from:

https://www.mhpbooks.com/classicist-says-quote-of-virgils-inscribed-on-911-memorial-is-shockingly-inappropriate/

NOTE WELL: the article the image is from says that this was about

Nisus and Euryalus and if we take the context into account, it is

not appropriate: typical of quotations: they get taken out of

context and acquire a life of their own: read on below: Mendelsohn

points this out as well .

Since the turn of the current century, there have been at least five

major translations into English alone, most recently by the American

poet David Ferry (Chicago), in the final installment of his

translation of Virgil’s complete works.

Still, the Aeneid—notoriously—can be hard to love. In part,

this has to do with its aesthetics. In place of the raw archaic

potency of Homer’s epics, which seems to dissolve the millennia

between his heroes and us, Virgil’s densely allusive poem offers an

elaborately self-conscious “literary” suavity. (The critic

and Columbia professor Mark Van Doren remarked that “Homer is a

world; Virgil, a style.”) Then, there’s Aeneas himself—“in some

ways,” as even the Great Courses Web site felt compelled to

acknowledge, “the dullest character in epic literature.” In

the Aeneid’s opening lines, Virgil announces that the hero is famed

above all for his pietas, his “sense of duty”: hardly the

sexiest attribute for a protagonist. If Aeneas was meant to be a

model proto-Roman, he has long struck many readers as a cold fish;

he and his comrades, the philosopher György Lukács once observed,

live “the cool and limited existence of shadows.” Particularly in

comparison with his Homeric predecessors, Aeneas comes up short,

lacking the cruel glamour of Achilles, or Odysseus’s beguiling

smarts.

But the biggest problem by far for modern audiences is the poem’s

subject matter. Today, the themes that made the epic required

reading for generations of emperors and generals, and for the

clerics and teachers who groomed them—the inevitability of

imperial dominance, the responsibilities of authoritarian rule,

the importance of duty and self-abnegation in the service of the

state—are proving to be an embarrassment. If readers of an

earlier era saw the Aeneid as an inspiring advertisement for the

onward march of Rome’s many descendants, from the Holy Roman

Empire to the British one, scholars now see in it a tale of

nationalistic arrogance whose plot is an all too familiar handbook

for repressive violence: once Aeneas and his fellow-Trojans arrive

on the coast of Italy, they find that they must fight a series of

wars with an indigenous population that, eventually, they brutally

subjugate.

The result is that readers today can have a very strange

relationship to this classic: it’s a work we feel we should embrace

but often keep at arm’s length. Take that quote in the 9/11

Museum: “No day shall erase you from the memory of time.” Whoever

came up with the idea of using it was clearly ignorant of the

context: these high-minded words are addressed to a pair of

nighttime marauders whose bloody ambush of a group of unsuspecting

targets suggests that they have far more in common with the 9/11

terrorists than with their victims. A century ago, many a

college undergrad could have caught the gaffe; today, it was enough

to have an impressive-sounding quote from an acknowledged classic.

Another way of saying all this is that, while our forebears looked

confidently to the text of the Aeneid for answers, today it

raises troubling questions. Who exactly is Aeneas, and why

should we admire him? What is the epic’s political stance? Can we

ignore the parts we dislike and cherish the rest? Should great

poetry serve an authoritarian regime—and just whose side was

Virgil on? Two thousand years after its appearance, we still can’t

decide if his masterpiece is a regressive celebration of power as

a means of political domination or a craftily coded critique of

imperial ideology—a work that still has something useful to tell

us.

Little in Virgil’s background destined him to be the great

poet of empire. He was born on October 15, 70 B.C., in a

village outside Mantua; his father, perhaps a

well-off farmer, had the means to provide him with a good education,

first in Cremona and Milan and then in Rome. The inhabitants of his

native northern region had only recently been granted Roman

citizenship through a decree by Julius Caesar, issued when the poet

was a young man. Hence, even after his first major work, a

collection of pastoral poems called the Eclogues, gained him an

entrée into Roman literary circles, Virgil must have seemed—and

perhaps felt—something of an outsider: a reserved country fellow

with (as his friend the poet Horace teased him) a hick’s haircut,

who spoke so haltingly that he could seem downright uneducated. His

retiring nature, which earned him the nickname parthenias (“little

virgin”), may have been the reason he decided not to remain in

Rome to complete his education. Instead, he settled in Naples,

a city with deep ties to the culture of the Greeks, which he and his

literary contemporaries revered. In the final lines of the Georgics,

a long didactic poem about farming which he finished when he was

around forty, the poet looked back yearningly to the untroubled

leisure he had enjoyed during that period:

And I, the poet Virgil, nurtured by sweet

Parthénopé [Naples], was flourishing in the pleasures

Of idle studies, I, who bold in youth

Played games with shepherds’ songs.

I’m quoting David Ferry’s translation of the poem. But the word that

Ferry translates as “idle” is somewhat stronger in the original:

Virgil says that his leisure time was ignobilis, “ignoble,” a choice

that suggests some guilt about that easygoing Neapolitan idyll. And

with good reason: however “sweet” those times were for Virgil, for

Rome they were anything but. The poet’s lifetime spanned the

harrowing disintegration of the Roman Republic and the fraught

birth of the Empire—by any measure, one of the most traumatic

centuries in European history. Virgil was a schoolchild when the

orator and statesman Cicero foiled a plot by the corrupt

aristocrat Catiline to overthrow the Republic; by the time the

poet was twenty, Julius Caesar, defying the Senate’s orders, had

crossed the Rubicon with his army and set in motion yet another

civil war. It was another two decades before Caesar’s great-nephew

and heir, Octavian, defeated the last of his rivals, the renegade

general Antony and his Egyptian consort, Cleopatra, at the Battle

of Actium, and established the so-called Principate—the rule of

the princeps (“first citizen”), an emperor in everything but name.

Soon afterward, he took the quasi-religious honorific “Augustus.”

The new ruler was a man of refined literary tastes; Virgil and

his patron, Maecenas, the regime’s unofficial minister of

culture, are said to have taken turns reading the Georgics aloud

to the Emperor after his victory at Actium. Augustus no doubt

liked what he heard. In one passage, the poet expresses a fervent

hope that Rome’s young new leader will be able to spare Italy the

wars that have wreaked havoc on the lives of the farmers whose labor

is the subject of the poem; in another, he envisages the erection of

a grand temple honoring the ruler.

Because we like to imagine poets as being free in their political

conscience, such fawning seems distasteful. (Robert Graves, the

author of “I, Claudius,” complained that “few poets have brought

such discredit as Virgil on their sacred calling.”) But Virgil

cannot have been alone among intelligent Romans in welcoming

Augustus’s regime as, at the very least, a stable alternative to

the decades of internecine horrors that had preceded it. If

Augustus did in fact suggest the idea for a national epic, it must

have been while Virgil was still working on the Georgics, which

includes a trailer for his next project: “And soon I’ll gird myself

to tell the tales / Of Caesar’s brilliant battles, and

carry his name / In story across . . . many

future years.” He began work on the Aeneid around 29 B.C. and

was in the final stages of writing when, ten years later, he died

suddenly while returning home from a trip to Greece. He was

buried in his beloved Naples.

The epic’s state of completion continues to be a subject of debate.

There’s little doubt that a number of lines are metrically

incomplete, a fact that dovetails with what we know about the

poet’s working method: he liked to joke that, in order to preserve

his momentum while writing, he’d put in temporary lines to serve as

“struts” until the “finished columns” were ready. According to

one anecdote, the dying Virgil begged his literary executors to

burn the manuscript of the epic, but Augustus intervened, and,

after some light editing, the finished work finally appeared. In the

epitaph he composed for himself, Virgil refers with disarming

modesty to his achievement: “Mantua gave me birth, Calabria took me,

now Naples / holds me fast. I sang of pastures, farms,

leaders.”

Virgil was keenly aware that, in composing an epic that begins at

Troy, describes the wanderings of a great hero, and features book

after book of gory battles, he was working in the long shadow of

Homer. But, instead of being crushed by what Harold Bloom

called “the anxiety of influence,” he found a way to acknowledge

his Greek models while adapting them to Roman themes.

Excerpts of the work in progress were already impressing

fellow-writers by the mid-twenties B.C., when the love poet

Propertius wrote that “something greater than the Iliad is being

born.”

The very structure of the Aeneid is a wink at Homer. The epic is

split between an “Odyssean” first half (Books I through VI recount

Aeneas’s wanderings as he makes his way from Troy to Italy) and an

“Iliadic” second half (Books VII through XII focus on the wars

that the hero and his allies wage in order to take possession of

their new homeland). Virgil signals this appropriation of

the two Greek classics in his work’s famous opening line, “Arms

and a man I sing”: the Iliad is the great epic of war

(“arms”), while the Odyssey begins by announcing that its subject is

“a man”—Odysseus. Virtually every one of the Aeneid’s nine

thousand eight hundred and ninety-six lines is embedded, like that

first one, in an intricate web of literary references, not

only to earlier Greek and Roman literature but to a wide range

of religious, historical, and mythological arcana. This

allusive complexity would have flattered the sophistication of the

original audience, but today it can leave everyone except

specialists flipping to the endnotes. In this way, Virgil’s

Homeric riff prefigures James Joyce’s, twenty centuries later:

whatever the great passages of intense humanity, there are parts

that feel like a treasure hunt designed for graduate students of the

future.

It is, indeed, hardly surprising that readers through the centuries

have found the Aeneid’s first half more engaging. As in the Odyssey,

there are shipwrecks caused by angry deities (Juno, the queen of the

gods, tries to foil Aeneas at every turn) and succor from helpful

ones (Venus intervenes every now and then to help her son). There

are councils of the gods at which the destinies of mortals are

sorted out; at one point, Jupiter, the king of the pantheon, assures

the anxious Venus (and, by implication, the Roman reader) that the

nation her son is about to found will enjoy imperium sine fine,

“rule without end.” As for the mortals, there are melancholy

reunions with old friends and family and hair-raising encounters

with legendary monsters. Virgil has a lot of fun retooling

episodes from the Odyssey: his hero has close calls with Scylla

and Charybdis, lands on the Cyclops’ island just after Odysseus

has left, and—in an amusing moment that does an end run around

Homer—decides to sail right past Circe’s abode.

And, like Odysseus, Aeneas is dangerously distracted from his

mission by a beautiful woman: Dido, the queen of the North

African city of Carthage, where the hero has been welcomed

hospitably after he is shipwrecked. Venus, eager for her son to find

a safe haven there, sends Cupid to make Dido fall in love with

Aeneas in Book I, and throughout Books II and III the queen grows

ever more besotted with her guest, who holds her court spellbound

with tales of his sufferings and adventures. His eyewitness

account of the sack of Troy, in Book II, remains one of the most

powerful depictions of military violence in European literature,

with a disorienting, almost cinematic oscillation between

seething, smoke-filled crowd scenes and claustrophobic moments of

individual panic. At one point, Aeneas, fleeing the smoldering

ruins, somehow loses track of his wife, Creusa; in a chillingly

realistic evocation of war’s chaos, we never learn how she dies.

As for Dido, her affair with the hero reaches a tragic climax in

Book IV. Aeneas, reminded by the gods of his sacred duty, abandons

her, and she commits suicide—the emotional high point of the epic’s

first half. (The curse she calls down on her former lover is the

passage that King Charles selected when he played the sortes

vergilianae.)

The Aeneid’s first part ends, as does the first half of the

Odyssey, with an unsettling visit to the Underworld.

Here, there are confrontations with the dead and the past they

represent—Dido’s ghost doesn’t deign to acknowledge the

apologetic Aeneas’s protestations—and encounters, too, with

the glorious future. One of the spirits that Aeneas meets is

his father, Anchises, whom he’d carried on his back as they

fled Troy, and who has since died; as Anchises guides his son

through the murky landscape, he draws his attention to a

fabulous parade of monarchs, warriors, statesmen, and heroes who

will distinguish the history of the future Roman state, from the

mythic king Romulus to Augustus himself. As they witness this

pageant, the old man imparts a crucial piece of advice. The

Greeks, he observes, excelled at the arts—sculpture, rhetoric—but

Rome has a far greater mission in world history:

“Well, I guess if breathing through your mouth has kept you alive

this far . . .”

Romans, never forget that this will be

Your appointed task: to use your arts

to be the governor of the world, to bring to it peace,

Serenely maintained with order and with justice,

To spare the defeated and to bring an end

To war by vanquishing the proud.

This conception of Rome’s strengths—administration,

governance, jurisprudence, war—in relation to Greece’s will be

familiar to anyone who’s taken a World Civ course. What’s so

confounding is that, after receiving this eloquent advice on

the correct uses of power, Aeneas—as the second half of the

poem shockingly demonstrates—doesn’t take it.

Books VII through XII, with their unrelenting account of the

bella horrida bella (“wars, horrible wars”)

that Aeneas must wage to secure his new homeland, are clearly

meant to recall the Iliad—not least, in the event that sets

them in motion. After the hero arrives in Italy, he favorably

impresses a local king named Latinus, who promises his daughter,

Lavinia, as a wife for Aeneas. The problem is that the

girl has already been chosen for a local chieftain named Turnus,

who, smarting from the insult, goes on to command the forces trying

to repel the Trojan invaders. And so, like the war recounted in

the Iliad, this one is fought over a woman who has been stolen

away from her rightful mate—the difference being that this time

it’s the Trojans, not the Greeks, who invade a foreign country and

ravage a kingdom in order to retrieve her. One challenge

presented by the mythic Trojan origins of the Roman people was that

the Trojans lost their great war; reshaping his source material,

Virgil found a way to transform a story about losers into an epic

about winners.

But what does it mean to be a winner? Anchises instructs his son

that, to be a Roman, he must become (in Ferry’s

translation) “governor of the world.” This rendering of Virgil’s

phrase regere imperio populos is rather mild. John

Dryden’s 1697 translation far better conveys the menace lurking in

the word imperium (“the right to command”): “ ’tis thine

alone, with awful sway, / To rule Mankind; and make the

World obey.”

Just what making the world obey looks like is vividly illustrated

in another vision of the future that the Aeneid provides. In

Book VIII, there is a lengthy description of the sumptuous shield

that Vulcan, the blacksmith god, forges for Aeneas before he

meets Turnus and the Italian hordes in battle. The decorations

on the shield meld moments both mythic and historical, past and

future, from Romulus and Remus being suckled by the she-wolf to a

central panel depicting the Battle of Actium, with Augustus and

his brilliant general Agrippa, on one side, facing off against

Antony and Cleopatra, on the other. (She’s backed by her

foreign “monster gods”: that “monster” is a telling bit of Roman

jingoism that Ferry inexplicably omits.) The shield also

includes an image of Augustus marching triumphantly through

the capital as its temples resound with the joyful singing of

mothers, while—that other product of imperium—a host of conquered

peoples are marched through the streets: nomads, Africans,

Germans, Scythians.

Yet one battle into which Aeneas carries his remarkable shield ends

with the hero unaccountably failing to adhere to the second part of

his father’s exhortation: to “spare the defeated.” As the poem

nears its conclusion, the wars gradually narrow to a

single combat between Aeneas and Turnus, who, by that point,

has slain a beautiful youth called Pallas, Aeneas’s ward and the son

of his chief ally. In the closing lines of the poem, Aeneas

fells Turnus with a crippling blow to the thigh. While his

enemy lies prostrate before him, the hero hesitates, sword in hand;

but, just as thoughts of leniency crowd his mind—he is,

after all, famous for his sense of duty, for doing the right thing—he

sees that Turnus is wearing a piece of armor torn from Pallas’s

body. Seized with rage and grief, Aeneas rips open Turnus’s breast

with one blow, and the dead man’s soul “indignant fled away to

the shades below.”

That is the last line of the poem—an ending so disorientingly

abrupt that it has been cited as evidence by those who believe that

Virgil left his magnum opus incomplete when he died. One

fifteenth-century Italian poet went so far as to add an extra book

to the poem (in Latin verse) tying Virgil’s loose ends into a neat

bow: Aeneas marries Lavinia and is eventually deified. This ending

was so popular that it was included in editions of the Aeneid for

centuries afterward.

As recently as the early twentieth century, the Aeneid was

embraced as a justification of the Roman—and, by extension,

any—empire: “a classic vindication of the European world-order,”

as one scholar put it. (This position is known among classicists as

the “optimistic” interpretation.) The marmoreal perfections

of its verse seemed to reflect the grand façades of the Roman state

itself: Augustus boasted that he found Rome a city of brick and left

it a city of marble.

But in the second half of the last century more and more

scholars came to see some of the epic’s most wrenching episodes as

attempts to draw attention to the toll that the exercise of

imperium inevitably takes. This “pessimistic” approach to the text

and its relation to imperial ideology has found its greatest

support in the account of Aeneas’s treatment of Dido. That

passionate, tender, and grandly tragic woman is by far the epic’s

greatest character—and, indeed, the only one to have had a

lasting impact on Western culture past the Middle Ages, memorably

appearing in works by artists ranging from Purcell to Berlioz to

Mark Morris.

After the gods order Aeneas to abandon Dido and leave Carthage—he

mustn’t, after all, end up like Antony, the love slave of an African

queen—he prepares to sneak away. But Dido finds him out and,

in a furious tirade, lambastes the man she considers to be her

husband for his craven evasion of a kind of

responsibility—emotional, ethical—quite unlike the political

dutifulness that has driven him from the start:

What shall I say?

What is there for me to say? . . .

There is nowhere where faith is kept; not anywhere.

He was stranded on the beach, a castaway,

With nothing. I made him welcome.

In uttering these words, Dido becomes the Aeneid’s most eloquent

voice of moral outrage at the promises that always get broken by

men with a mission; in killing herself, she becomes a

heartbreaking symbol of the collateral damage that “empire” leaves

in its wake.

Aeneas’s reaction to her tirade is telling. Unable to bring himself

to look her in the eye, he looks instead “at the

future / He was required to look at”:

Pious Aeneas, groaning and sighing, and shaken

In his very self in his great love for her,

And longing to find the words that might assuage

Her grief over what is being done to her,

Nevertheless obeyed the divine command

And went back to his fleet.

You wish that Ferry hadn’t translated the Latin word pius in the

first line of this passage as the English word it so closely

resembles, “pious”; here more than anywhere else, pius means

“dutiful,” embodying a steadfast obedience to the gods’ plan which

overrides every other consideration. Much of the Aeneid is

fuelled by this torturous conflict between private fulfillment and

public responsibility, which was to become a staple of European

literature and drama, showing up in everything from Corneille

to “The Crown.” (You sometimes get the impression that Virgil

himself would like to be free of his poetic duty to celebrate the

empire. In Book V, a long set piece about a sailing competition that

Aeneas holds for his men, filled with verve and humor, feels like a

vacation for the poet, too.)

When Aeneas does reply to Dido, he’s as cool as a corporate

lawyer, rattling off one talking point after another. (Dido has a

kingdom of her own, so why shouldn’t he?) But how are we to

reconcile this Aeneas with the distraught figure we’re left with

at the end of the poem, a man who goes berserk when he’s reminded

of the loss of his young ward and who brutally slays a captive

supplicant? The contradiction has led to persistent questions

about the coherence of Virgil’s depiction of his hero. When

critics aren’t denouncing Aeneas’s lack of personality (“a stick

who would have contributed to The New Statesman,” Ezra Pound

sniffed), they’re fulminating against his lack of character. “A

cad to the last” was Robert Graves’s summation.

“No wonder you can’t go on. It’s those goddam shoes you’re wearing!”

And as with the hero so, too, with the epic itself: for many

readers, something doesn’t add up. If the Aeneid is an admiring

piece of propaganda for empire triumphant, whose hero emblematizes

the necessity of suppressing individuality in the interest of the

state, what do you do with Dido—or, for that matter, with Turnus,

who could well strike readers today as a heroic native resisting

colonial incursion, an admirable prototype of Sitting Bull? And if

it’s a veiled critique of empire that movingly catalogues the

horrible costs of imperium, what do you do with all the imperial

dazzle—the shield, the parade of future Romans, the apparent

endorsement of the hero’s dogged allegiance to duty?

Latin is a rather chunky language. Unlike Greek, which is far more

supple, it has no definite or indefinite articles; a page of Latin

can look like a wall of bricks. As such, it’s particularly difficult

to adapt to dactylic hexameter, the waltzlike, oom-pah-pah meter of

epic poetry, which the Romans inherited from the Greeks. One of

Virgil’s achievements was to bring Latin hexameter verse to an

unusually high level of flexibility and polish, stretching long

thoughts and sentences over several lines, gracefully balancing

pairs of nouns and adjectives, and finding ways to temper the

natural heaviness of his native tongue. Alfred, Lord Tennyson,

called the result “the stateliest measure ever moulded by the lips

of man.”

David Ferry more than succeeds in capturing the stateliness, as

his rendering of the Proem, the epic’s introductory lines, into

English blank verse shows:

I sing of arms and the man whom fate had sent

To exile from the shores of Troy to be

The first to come to Lavinium and the coasts

Of Italy, and who, because of Juno’s

Savage implacable rage, was battered by storms

At sea, and from the heavens above, and also

By tempests of war, until at last he might

Bring his household gods to Latium, and build his town,

From which would come the Alban Fathers and

The lofty walls of Rome.

Alone among recent translators, as far as I am aware, Ferry

has honored the crucial fact that, in the original, this is all

one long flowing sentence and one thought: from Troy to Rome, from

past to present, from defeat to victory.

But there’s more to Virgil than high polish. Because the Aeneid’s

instantaneous status as a classic made its style a standard, it’s

difficult to appreciate how innovative and idiosyncratic

Virgil’s poetry once felt. One favorite device, for

instance, is called “enallage,” in which an

adjective is pointedly displaced from the noun it should,

logically, modify. Take the last line of the Proem, with its

climactic vision of what Ferry renders as “The lofty walls of

Rome.” What Virgil actually wrote was stranger: “the walls of

lofty Rome.” The poet knew what he was doing—“lofty walls” is

about architecture, but “lofty Rome” is about empire.

Ferry’s creamily elegant rendering of the epic, which tries to

“correct” the text’s oddness, is likely to leave you wondering why

critics both ancient and modern have scratched their heads over

Virgil’s verse—his occasionally jarring or archaic diction (mocked

by one Roman littérateur who made his point by writing a parody of

the poet’s early work); his “tasteless striving for effect,” as

Augustus’s friend and general Agrippa complained; his “use of words

too forcible for his thoughts,” as A. E. Housman put it two

millennia later. It’s these arresting qualities that made Virgil

feel modern to his contemporaries—something it’s almost impossible

to feel about him in this translation and so many others.

But perhaps we don’t need a translation to drag the Aeneid into the

modern era. Maybe it’s always been here, and we’re just looking at

it from the wrong angle—or looking for the wrong things. Maybe

the inconsistencies in the hero and his poem that have distressed

readers and critics—the certainties alternating with doubt, the

sudden careening from coolness to high emotion, the poet’s

admiring embrace of an empire whose moral offenses he can’t help

cataloguing, the optimistic portrait of a great nation rising

haunted by a cynical appraisal of Realpolitik at work—aren’t

problems of interpretation that we have to solve but, rather, the

qualities in which this work’s modernity resides.

This, at any rate, is what was going through my mind

one day fifteen years ago, when, I like to think, I finally began to

understand the Aeneid. At the time, I was working on a book about

the Holocaust, and had spent several years interviewing the few

remaining survivors from a small Polish town whose Jewish population

had been obliterated by what you could legitimately call an exercise

of imperium. As I pressed these elderly people for their memories, I

was struck by the similarities in the way they talked: a kind of

resigned fatalism, a forlorn acknowledgment that the world they were

trying to describe was, in the end, impossible to evoke; strange

swings between an almost abnormal detachment when describing

unspeakable atrocities and sudden eruptions of ungovernable rage and

grief triggered by the most trivial memory.

Months later, when I was back home teaching Greek and Roman classics

again, it occurred to me that the difficulties we have with

Aeneas and his epic cease to be difficulties once you think of him

not as a hero but as a type we’re all too familiar with: a

survivor, a person so fractured by the horrors of the past that he

can hold himself together only by an unnatural effort of will,

someone who has so little of his history left that the only thing

that gets him through the present is a numbed sense of duty to a

barely discernible future that can justify every kind of

deprivation. It would be hard to think of a more modern figure.

Or, indeed, a more modern story. What is the Aeneid about? It is

about a tiny band of outcasts, the survivors of a terrible

persecution. It is about how these survivors—clinging to a divine

assurance that an unknown and faraway land will become their new

home—arduously cross the seas, determined to refashion themselves

as a new people, a nation of victors rather than victims. It is

about how, when they finally get there, they find their new

homeland inhabited by locals who have no intention of making way

for them. It is about how this geopolitical tragedy generates new

wars, wars that will, in turn, trigger further conflicts: bella

horrida bella. It is about how such conflicts leave

those involved in them morally unrecognizable, even to themselves.

This is a story that both the Old and the New Worlds know too

well; and Virgil was the first to tell it. Whatever it meant in the

past, and however it discomfits the present, the Aeneid has, alas,

always anticipated the future. ♦

This article appears in the print edition of the October 15, 2018,

issue, with the headline “Epic Fail?”

• Daniel Mendelsohn is the

author of the memoir “An Odyssey: A Father, a Son, and an Epic.” He

teaches at Bard College.

Read more »