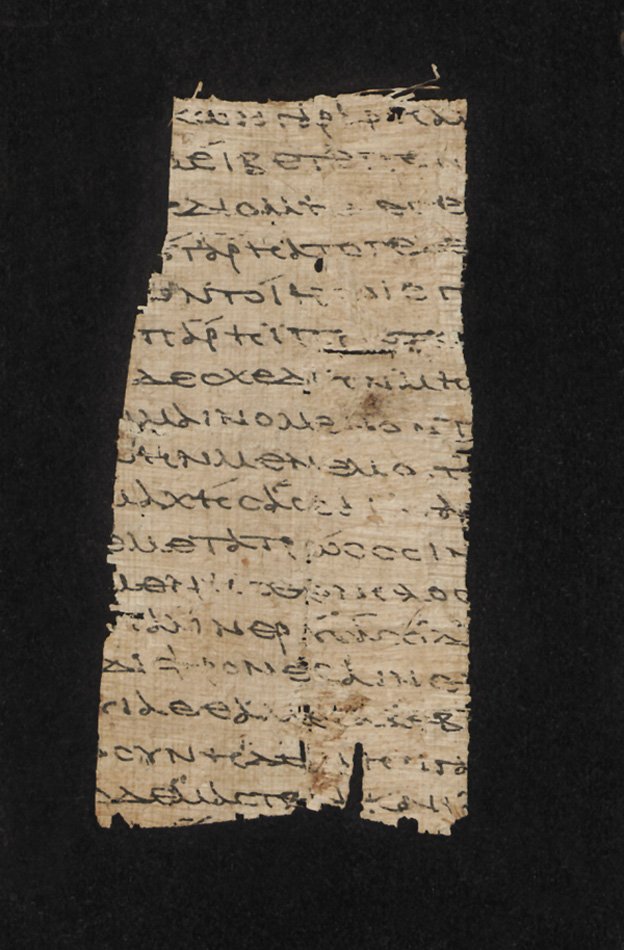

Who are these people? How do we know?

5th c. BCE vase from Chiusi archaeological museum: https://www.akg-images.co.uk/archive/-2UMDHUQ85I9Q.html

NOTE THAT ON THE SCHEDULE THERE IS AN ASSIGNMENT FOR NEXT WEEK:

propose what you would like to do for the 30% of your grade that

is made up of material you choose. This is a proposal, and it will

probably have to change, either because of your own changes of

choice or because of factors on our end.

UNLESS YOU HAVE A VERY GOOD REASON NOT TO DO A POSTER, everyone

should do a poster and propose a topic area for your poster.

Who are these people? How do we know?

5th c. BCE vase from Chiusi archaeological museum: https://www.akg-images.co.uk/archive/-2UMDHUQ85I9Q.html

That little justification of the Telemachy's place in Odyssey

could be read as part of the creation of a plot (a complication, a

resolution, a "story" with obvious beginning, middle, end), all

via the device of Athena, who seems to drive the whole thing

(watch her in this epic!).

So, in terms of important concepts of plot and story, we have:

All of these elements are part of the artifice and effect of an

author or singer. Instead of thinking of "plot" as one singular

thing, for now let's keep these descriptive names clear in our

mind, ones like "chronological sequence of events" and "order of

exposition" and "causal structure" and "beginning, middle, end

structure" because then we won't be as confused as if we think

"plot" means one of them or "story" means one of them. But as you

continue in literary analysis, you will find that people use terms

with different definitions. Not just literary analysis.

There is also something called "functional equivalent" that helps

us to analyze literature. The rage of Achilles seems to serve the

same role in Iliad as the problem of the suitors in the Odyssey:

it creates a unity, and it gives the story an obvious starting and

ending point in time. "Homer" chooses exactly where to plop us

down in medias res on the timeline by choosing the rage

of Achilles and the problem of the suitors: a way of making the

narrative more interesting/suspenseful/artistic.

The structure and tension and direction

are all the product of artifice. Perhaps "Homer" was the

artificer: perhaps that is why his name is attached to these 2

epics which are part of a much bigger set of epics, whose

"authors" are a whole community (cf. Lang's thesis about Iliad).

But we don't know that: we do know that these two epics stand out

from the epic cycle b/c they are complex works with all the

elements we just identified.

Was it one author? Maybe. Who knows. Note that Odyssey

tells bits about the war, but almost never does it retell

something in the Iliad: it tells about the horse, about

Odysseus' spying mission into Troy, etc., but does not repeat

episodes from Iliad. What could account for that? Maybe

over time, the two epics sorted things out and settled into a

non-overlapping pattern? Or, maybe, one bard decided what to cover

in both and purposely didn't overlap? Or, maybe, one tradition is

younger than the other and just naturally didn't overlap the older

one, but told other things. All of those would be 'sufficient'

explanations, but we cannot confirm which, if any, are right.

But trying to tie authorship by "Homer" to this is really a

distraction for us today: the point is that both Iliad

and Odyssey have plot: By choosing a

problem in a much larger story (one chooses Achilles' rage, the

other the problem of the suitors), they construct plot: they weave

the rest of the story into that plot, but they are not telling the

rest of the story straightforwardly.

The most remembered part of Odyssey: his

fantastic wanderings

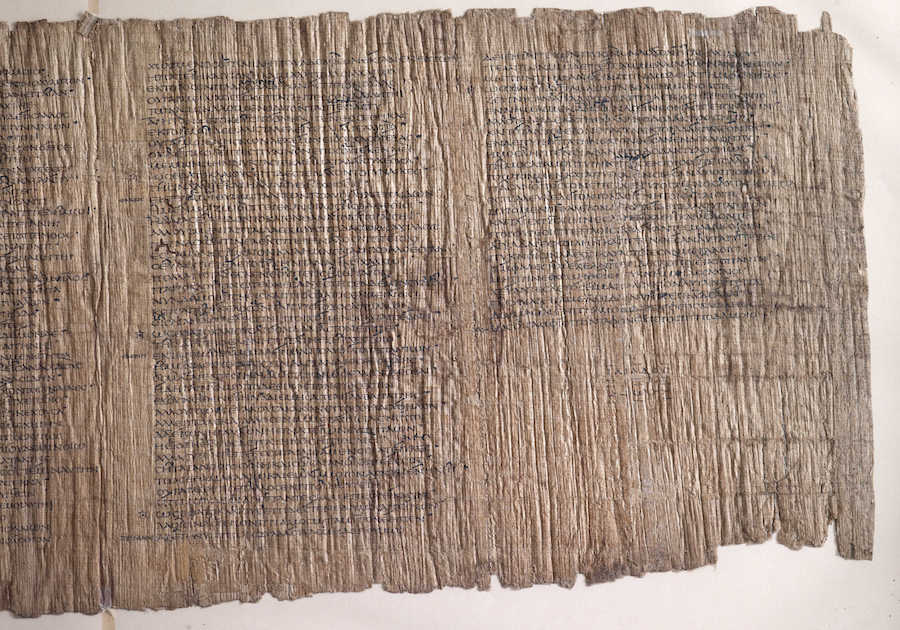

Roman wall painting from a house in Rome on the Esquiline hill,

interpreted as Odysseus' ships v. the Laestrygonians: why not

the Cyclops?

https://blog.oup.com/2014/07/scenes-from-the-odyssey-in-ancient-art/

The "great wanderings" of Odysseus are ONLY in Books 9-12 (from

when he blinds the Cyclops and gets Poseidon angry at him until he

lands on Phaeacia). Those wanderings:

These fantastic places where cyclops live, or where lotus-eaters

live, or where Scylla and Charybdis catch sailors, or where Circe

lives, or where Calypso lives: are they imaginary?

or are they real? There are champions

of both views.

Some people want to locate those fantastic places in the real

places that in later ages claimed to be those sites (we know that

various places did claim to be each of the sites in Odyssey

from much later writers).

BUT: There is a problem with their claims: all the places

identified as the fantastic places in the Odyssey had

Greek colonies that either were founded in the late 8th century

(i.e. well after we think the Odyssey took shape) or their

habitation dates back to Mycenaean times (i.e. they were Greek

places already). In other words, they were known real places

already at the time of writing down the epics (late 8th century).

How could they both be known places with real Greeks AND

fantastical/wild?

It's not impossible to reconcile them: Homer is after all talking

about a distant past. Perhaps the problem can be avoided with the

hand-waving of saying that it's just a mash-up of history that

doesn't quite match what we know, both what we know from what we

moderns find on the ground via archaeology and what the ancients

knew at various times.

This is all rendered more complex by the fact that the

epics themselves speak of just about all of those real places that

later came to be identified with the fantastical places, and they

speak of them as real places with their real names! More mash-up?

just inconsistency? or evidence that they are just imaginary, not

meant to be real at all?

Even the land of the dead is not described as in an under-world,

I think: it is just a far shore. So is it real? Some previious

students in this class found a river/spring on the Peloponnese

that is supposedly the Styx!

Another tack: Many have seen the wanderings as allegorical

of human life. Maybe. Certainly works for later readers.

They certainly represent trials, trials of sheer

perseverance and strength and skill, but also trials of

temptation. They show Odysseus' physical strength, his ingenuity,

his sheer willpower. Perhaps they are allegorical of the Human

condition. They fulfill the first line of the poem.

But Lattimore, a famous translator of Homer, in his introduction,

tells us that such allegorical reading is not at all likely to

have been the bards' intent: it is a use that later ages put the

stories to. Which is true: they did: but what backs up Lattimore's

claim that earlier ages didn't allegorize it? Perhaps just the

fact that we have nothing like clearly labeled/identifiable

allegory from that age. And also, Odysseus seems to be one

particular individual and may not be terribly allegorizable as

"any human."

![]()

https://heliconstorytelling.com/homer-storytelling/

AND YET, let's try another tack: when Nestor tells a tale, it has

a purpose, the very telling has a purpose. He uses the tale to say

something to someone else. Ditto for Phoenix telling the tale of

the Calydonian boar hunt. These tales within the narrative magnify

the wisdom and experience of their tellers and also offer

parallels and commentary on what is happening at the time in the

narrative.

Maybe Odysseus' tales have a purpose too. Maybe his telling tales

of his wanderings and trials are all designed for a purpose, a

rhetorical one that suits the occasion and advances toward the

storyteller's goal, strengthens their case. Like those people in a

Star Trek episode who only communicate thru stories? Is this

Odysseus' self-justification? To get his audience (Phaeacians,

etc.) to give him what he wants? His stories do accomplish that.

Odysseus also, separately from the great wanderings that he tells

in Books 9-12, tells 5 clearly false stories that are

meant to be plausible and are not fantastical, in answer to the

"Who are you? and where from?" question. They involve known

geographical places. They fit in with the other heroes' returns

from Troy. They could be conveying historical reality (in the way

that Homer does: a mashup of history and mythology which poet and

audience believe really happened that way).

This is a really complex narrative space and the construction of

place and plot and character is not accidental, not just a

chronicler telling episodes one after another that have little

unity. Like Iliad, it is all tied up together into ONE

giant knot that has a bow on top!