|

To discover more about the history of the University of Vermont campus central and east areas, UVM students: Emily Baker, Erin Briggs, Julia Brown, Robin Fordham, Noah Sandweiss, Cheyenne Stokes, and Brooke Talbott conducted this research during the Fall 2021 semester in the Historic Preservation 206: Researching Historic Structures and Sites course taught by Professor Thomas Visser of the UVM History Department and UVM Historic Preservation Program.

Major research sources include UVM Silver Special Collections Library, University Archives and photographs curated by the UVM Landscape Change Program, as well maps, yearbooks, newspapers and postcards, combined with on-site field research, interviews, memories and experiences. This web site was designed in the HP 206 class, then edited and coded by Prof. Visser. Previous HP 206 class projects that have researched areas of the UVM campus include: UVM Redstone Campus History (2019) and the UVM Green Area Heritage Study (2011).

We acknowledge that the land of the University of Vermont is the traditional territory of indigenous peoples. |

|

Johnson House (1806/1906/2005)There is often a tension between keeping and demolishing buildings on a college campus. Sentimentalists decry any destruction of the old to make way for the new. Modernists insist that progress marches on and advocate for the necessity of the old falling to allow for new creative forms. Occasionally however the tension of the need for a building site and its historic importance results in another outcome - the relocation of a building in its entirety. UVM’s Johnson House was significant enough to endure this undertaking not once, but twice. Built in 1806 in the Federal style,1 Johnson House was built on the corner of Main St. and University Place for Moses Catlin and his wife Lurinda as part of a twenty-two acre farm.2 Catlin was born in Litchfield, CT in 1770, and emigrated to Burlington around 1790. He was elected Selectman of Burlington 1806, and later went on to erect the Burlington Flour Mills at Winooski Falls with his brother Guy.3

Catlin sold the house to John Johnson, Vermont's first surveyor, in 1809. Johnson was an accomplished and prolific designer and engineer who oversaw the construction of numerous important buildings and bridges in the northern Vermont area, including Grasse Mount (1804) and Old Mill (1824-9) in Burlington. The 1830 Ammi B. Young map of Burlington shows the house as an L-shaped structure with outbuildings attached to the southeast corner and just to the east. These features are shown in more detail on an 1843 map by Edwin Johnson. An image from UVM Special Collections shows the building as it appeared around 1880 at its original location facing the UVM Green. In 1902, J.J. Allen, a direct descendant of Johnson, sold the family homestead to the University, and Johnson House became a part of the Agricultural College. In 1906, in order to make room for the new Morrill Hall, the building was moved up the street (then called Williston Turnpike) to its second location at 590 Main Street.4

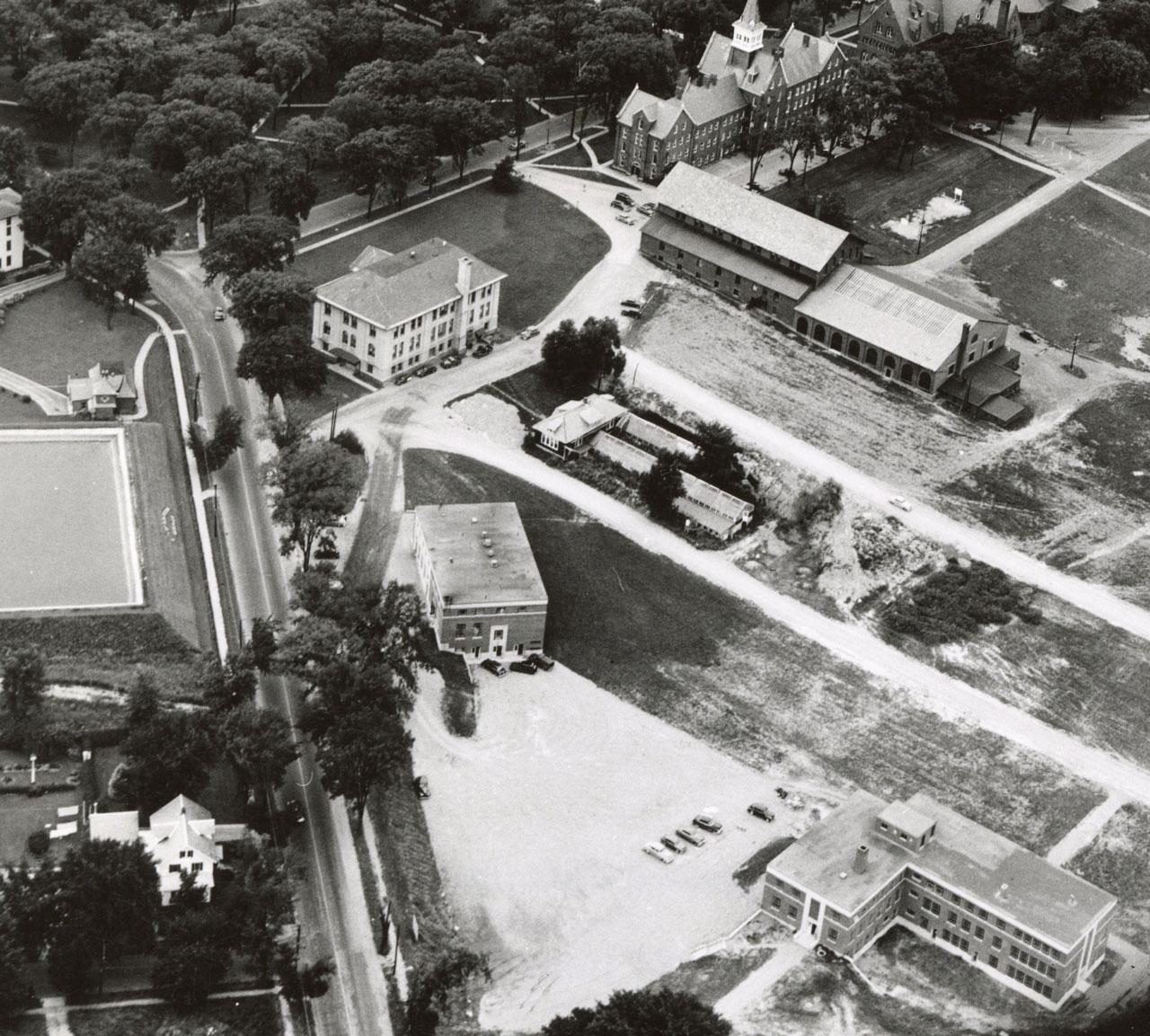

1961 aerial view looking northeast showing Johnson House (right) on the north side of Main Street, with Terrill Hall at left and Hills Building with greenhouses above. UVM Special Collections. Johnson House has seen many uses over 215 years. The house was remodeled as living quarters for farm hands working on the nearby University Farm. The UVM Agronomy Department called it home from 1928 to 1950. During this period, a greenhouse was added on the southeast corner. UVM School of Dental Hygiene occupied Johnson House from 1950 to 1987. Later, the building housed offices for UVM Police Services, the UVM Historic Preservation Program's Visual Laboratory Project and the Center for Sustainable Agriculture.

Main Street looking west, May 2000, with Johnson House at right and the Carrigan Dairy Science Building and Morrill Hall beyond. Photo by Thomas Visser In 2002, Johnson House became the home of the Gund Institute for Ecological Economics. By 2003, the University had moved forward with plans to build a new student center on a substantial site between Morrill Hall and University Heights. This project would call for the removal of the University Store, Carrigan Dairy Science Building, Terrill Hall, the UVM Farm Building, and Johnson House. Only Johnson House and Terrill Hall were deemed historically significant enough to escape demolition. Terrill Hall was fully incorporated into the Davis Center plan, while Johnson House changed locations for the second time in its history. The 2003 building evaluation report noted that “the Johnson House has the potential to be restored in a manner that will return it to the visual distinction it possessed during the 19th and early 20th century,” treatment it received after its second relocation.5 On July 7, 2005, the 4,300 square foot, this two-story building was moved across the street to its current location at 617 Main.6 The house weighed 145 tons and was moved 150 feet at an average rate of five feet per minute for a cost of $125,000.7

Moving Johnson House across Main Street, July 2005. Photo by Thomas Visser

Johnson House at 617 Main Street, view looking south, 2021. Photo by Robin Fordham Notes1. Liz Pritchett, “Historic Buildings Evaluation Report: Act 250 Review” (Burlington, Vermont: Liz Pritchett Associates, 2003), pp. 1-18, 2. 2. Johnson house - 617 main street - history. Accessed November 11, 2021. http://www.uvm.edu/campus/590main/590mainhistory.html. 3. “Guy Catlin Papers,” Collection: Guy Catlin Papers | Finding Aids, accessed November 11, 2021, http://scfindingaids.uvm.edu/repositories/2/resources/127. 4. Pritchett, “Historic Buildings,” 2. 5. Ibid, 6. 6. Erica Jacobson, “UVM Moves the Johnson House,” Burlington Free Press, July 8, 2005, 1C. 7. Ibid. |

|

Torrey Hall (1863)By Erin Briggs Since its creation in 1791, the University of Vermont has undergone a vast and variety number of changes, including the many buildings around campus, with each of them giving opportunities for stories to be told. One building that falls perfectly into the category of changes through time and storytelling is Torrey Hall. It sits on the central part of campus, right at the heart, surrounded by both old and newer buildings. It has a long history, as it housed a variety of collections and activities, including a library, a museum, an art center, and meeting rooms. Its history can be found throughout stories told about this campus and its people.

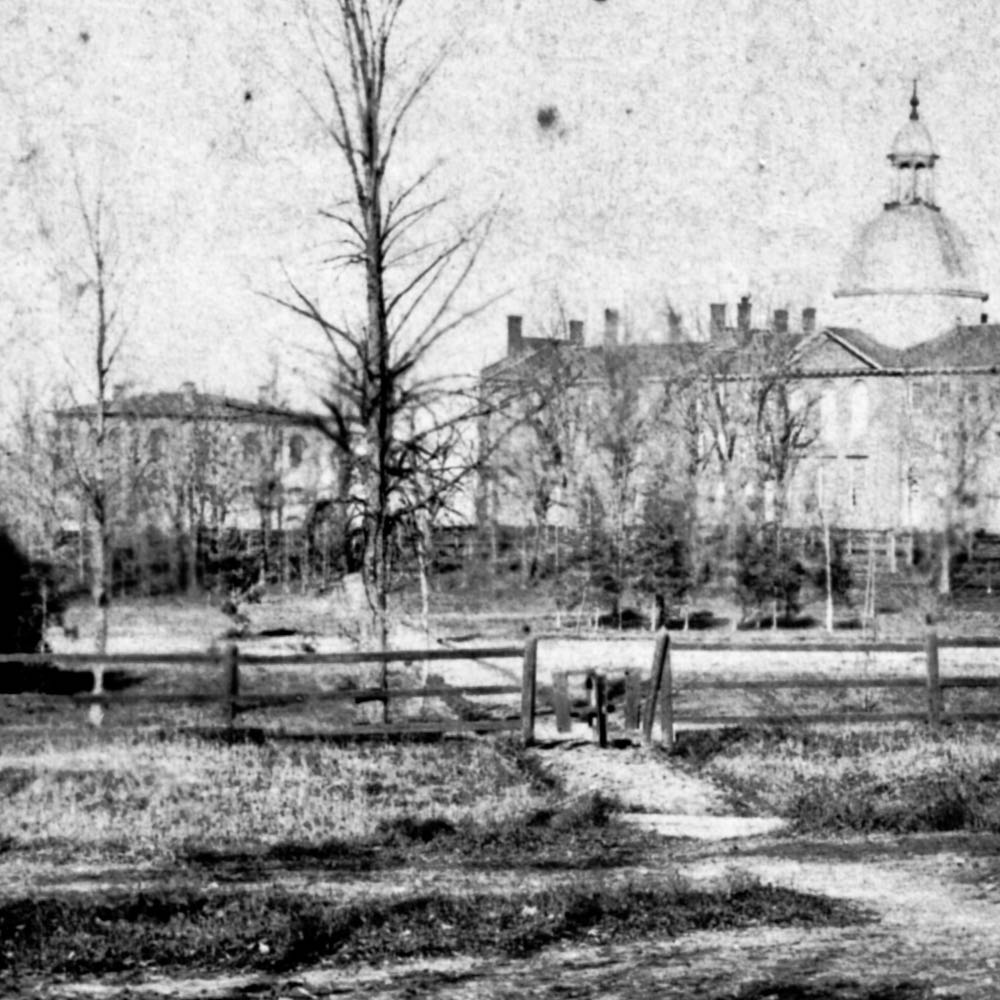

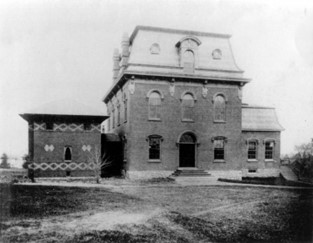

UVM Green looking east circa 1870, showing Old Art Building (left) and Old Mill (right). UVM Archives Built in 1863, initially named the Old Art Building, it is an impressive two-story rectangular brick block, measuring 40 by 60 feet, with the museum and library housed in the first and second floor, respectively. Opening as the University’s first library, it was clearly important and was given a prominent location facing the Green as part of University Row.1 In 1874, the building saw its first change. A third floor and mansard roof were added, giving it the traditional Second Empire style. The designer of the addition, T.W. Park, also gifted an art collection to the University, which sat in that very floor he added.2 Due to the opening of Billings Library the University’s library collection moved out and into Billings. This led to the art collection turned museum being expanded to the second floor in 1885.3 Its second major change came in 1895, with the plan of building Williams Science Hall in that location. The then Old Art Building was moved to a new location and rotated to face south. Along with its new home came new additions. Around 1900, east and west wings were added. On the east side, a two-story wing, was built similar to the main block, which is seen in the roof, windows, and materials. This wing became home to classrooms for geology, anthropology, and other similar programs. The one-story west wing was built for housing the Henry LeGrand Cannon Collection. Cannon traveled around East India and Southeast Asia collecting objects, which were donated to the University upon his death.4 These were later studied by George Perkins, leading to the development of the first anthropology courses in the United States.5

Torrey Hall, circa 1900. View looking north. UVM Archives / UVM Landscape Change Program Over time the then Old Art Building continued to change, but still focused on housing educational and artistic collections. By 1942 the building was known as the Art Center, since it became the new studio art center.

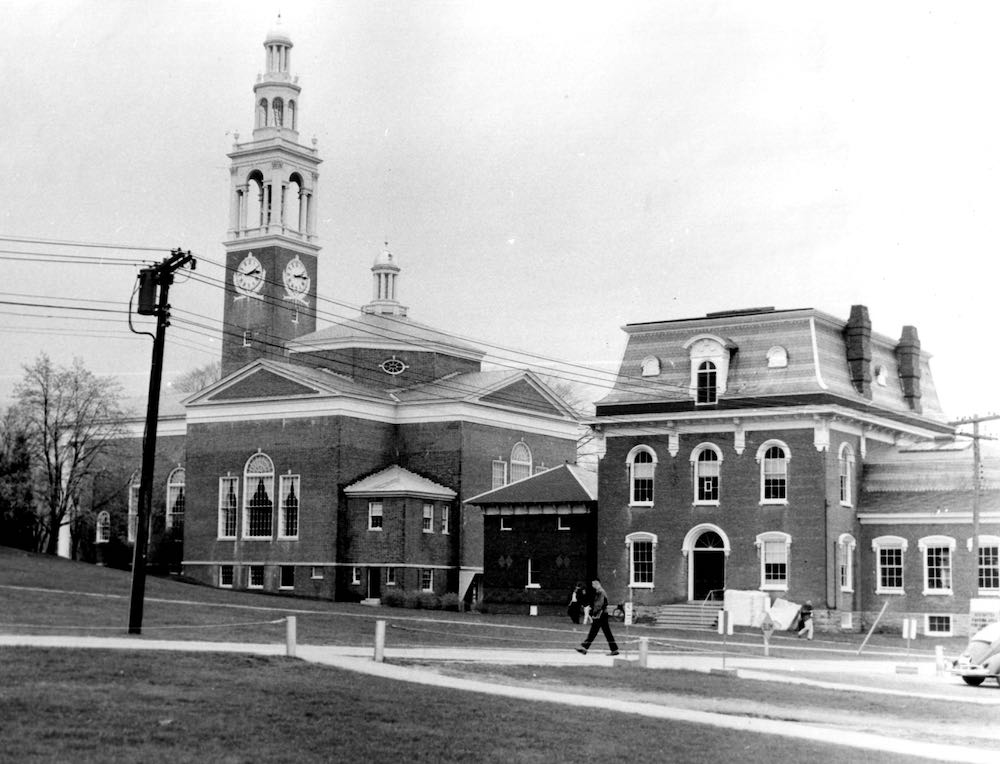

Ira Allen Chapel and "Art Center" / Torrey Hall, circa 1960. View looking southwest before construction of Votey Hall. UVM Archives Another significant change came in September of 1975 with a name change, that being what we know today: Torrey Hall. Named after Joseph Torrey, for the instrumental roles he played at the University. These consisted of the Chair of Greek and Latin (1827), Professor of Intellectual and Moral Philosophy (1842), and President of the University from 1862 to 1866.6 He was present at the building’s first dedication as a library, since it was constructed during his first year of presidency. Much of the library collection was purchased and put together by Torrey, obtained from his 1834 travels across Europe.7 In addition, he is believed to be the “first in the United States to give lectures on “The Philosophy of Art.” 8 He is said to “[exemplify] the character of this University and the individuals who have given it leadership as scholars and administrators.” 9 This led to people present at the renaming to feel honored, as many were his descendants. He was greatly influential and helped to carve this University into what it is today. This dedication also marked change for Torrey Hall’s purpose. After its new name it became home to the Pringle Herbarium with its numerous plant specimens, and the textile design and weaving programs of the School of Home Economics.10 By 1974, after standing for more than one hundred years renovations were done. This included “new heating, power, and lighting systems, new floor plans for each story, and significant exterior modifications.” 11 Slate shingles replaced the old asphalt ones, a chimney was removed, and the south façade steps were enlarged, and an elevator was installed.12 Following the renovations, in April of 1975 it was nominated to the National Register of Historic Places as a contributor to the University Green Historic District. By the 1990s, the Pringle Herbarium continued its stay in Torrey Hall but was joined by the Thompson Natural History Collection, the Churchill Library, and some classrooms. These stayed here until somewhat recently. In 2016 exterior renovations to the slate mansard roof began but were interrupted in 2017 due to a fire. On August 3, 2017, a fire broke out engulfing the upper floors, as construction workers were renovating the building. The fire department had the fire out by 3pm that same day. While the fire and smoke damage were limited to the upper floors, the overall damage was extensive. Water from hosing the flames had leaked down through all the floors and caused significant damage, according to Fire Chief Locke.13 Many of the collections remained largely intact, but some damage was present in the plant collection, as that was housed on the top floor.

Torrey Hall fire damage, 2017. Photo by Thomas Visser Despite the fire, exterior renovations were completed the following April of 2018. Most of the Pringle Herbarium’s specimens were sent to an archival recovery facility, that is, the ones that did not dry within a day.14 The entire natural history collections were moved to multiple locations on campus, from attics to storage rooms. Academically and socially Torrey may not seem important anymore, but it should, since so many stories from its history and changes have been told. Its stand through time and the changes time ensues ensures that history cannot be forgotten, and inspiring stories can come from history and changes. Currently Torrey Hall is vacant, not open to the public and all of the collections have been relocated due to the extensive interior water damage in the building.

Torrey Hall interior, 2018. Photo by Thomas Visser

Torrey Hall, 2021 view looking north. Photo by Erin Briggs Notes1. “Old Art Building,” University Green National Register Nomination, 1973, 5-6. 2. “Art Building,” November 1948, VT. 3. Sophia Trigg, “A brief history of UVM’s Torrey Hall,” Burlington Free Press, (2017) 5A, accessed September 19, 2021, https://www.burlingtonfreepress.com/story/news/2017/08/03/brief-history-uvms-torrey-hall/536316001/. 4. Ariadne Argyros, “Henry LeGrand Cannon,” House to Home, accessed November 4, 2021, https://blog.uvm.edu/jadickin-anth250home/2018/0417/henry-legrand-cannon/. 5. Ibid. 6. “The Man and the Building,” October 4, 1975, Dedication Invitation, Burlington, VT. 7. Larry Van Benthuysen to Anne Torrey Fruen, December 1974. University of Vermont Special Collections, Burlington, VT. 8. “The Man and the Building,” October 4, 1975, Dedication Invitation, Burlington, VT. 9. Ibid. 10. “Torrey Hall Dedication is a Family Affair,” University of Vermont This Week (Burlington, VT), October 13, 1975. 11. Sarah Farley, “Torrey Hall: Past and Present,” The University of Vermont Campus Treasures Website, December 1999, http://www.uvm.edu/~campus/torrey/torreyhistory.html. 12. Ibid. 13. Joel Baird, “Fire causes ‘significant’ damage to historic UVM hall,” The Burlington Free Press, (2017), https://www.burlingtonfreepress.com/story/news/2017/08/03/fire-blazes-uvms-torrey-hall/535759001/. 14. Torrey Hall Renovation,” The University of Vermont Natural History website, https://www.uvm.edu/vtnaturalhistory/torrey-hall-renovation. |

|

Perkins Hall (1891)By Erin Briggs The history of the Perkins Hall spans over a century, more specifically it turns 130 years old this year. During this time, it has been used as a multitude of services, the most notable being a home for the Museum and Department of Geology. Although it is still in use and people are taking part in building a sense of place around it, it is not as prominent as when the museum called it home. Built in 1891, it would not be known as the Perkins Hall in years to come. From 1894 to at least 1919 it was named the Electrical and Mechanical Building, which is seen on the Burlington fire insurance maps.

Perkins Hall, circa 1990. UVM Archives / UVM Landscape Change Program It later became home to the University’s engineering program until Votey Hall was constructed, which became the building for the engineering programs. When the Engineering Department left the building, the University finally had a building to use for geology, which has not happened since before the Fleming Museum was built.1 This would not have been possible without the completion of the Votey Engineering Building because before there was no available space for the Geology Department.2 Prior to being housed on the UVM campus, the museum specimens came from the official Vermont State collection in Montpelier.3 The collection was housed in Old Mill from 1826 to 1862. It was later stored in Torrey Hall until 1931. From there it was moved to the Robert Hull Fleming Museum filling until 1945 when Perkins Museum of Geology was established in the Perkins Hall.4 In this new home for geology the building opened to a collection of dinosaur tracks, murals, a variety of minerals, and a plaster model of the Grand Canyon, “which during moving, had to be sawed apart and neatly rejoined.”5 It had multiple laboratories, one for “the more elementary study of geology” and others for paleontology, mineralogy, sedimentation, and more.6 In addition, the upstairs space has offices for the chair of the department, the department secretary, state geologist, and paleontologist. With over 12,000 specimens in geology and related fields a portion of their existence in the collection due to Professor George H. Perkins. The Perkins Hall and Perkins Museum of Geology’s eponym, George Perkins was influential in this field of study. Born in Cambridge, Massachusetts, he grew up to be a professional in his field with multiple degrees from Yale University. He became a professor at the University of Vermont, where in 1886 he taught “one of the first undergraduate courses in anthropology in the United States.”7 He held the Professor of Natural History position until 1926. From 1898 to 1933, at his death, he served as the 8th Vermont State Geologist.8 During his time in this position he established the Vermont Geological Survey, conducted research and many reports, and reported on the Vermont mineral industry.9 His passion for gaining and giving knowledge and information continues to live in the Geology Museum and geology program. By the 1990s there was a search for progress. In 1992 the Museum of Geology curator, Jeff Howe, had a goal of transforming the museum. He wanted the museum of the past, “full of dusty curios in velvet-lined glass cases,” changed into one that reflected newer times.10 According to Howe, “The old theory of museums was to provide the exotic. But because of the TV the exotic has become commonplace, and the commonplace has become exotic.”11 He wanted the museum as a showcase for Vermont’s geology, like the 12,000 year old whale skeleton found in Charlotte, and not a three dimensional model of the Grand Canyon, which they happened to be in search of a new home for.12 By July of 1994 the museum hit a budget crunch, when the Lintilhac Foundation’s grant expired. Despite this, displays were kept open, with around 3,000 visitors annually.13 Without the funding, the museum director position was eliminated, forcing Howe to find work elsewhere. Before this he and geology graduate students “built a computer database that took stock of the thousands of geologic specimens that had been chucked into the basement of the Perkins Hall.” 1 By 2002, over 5,000 specimens were digitally categorized on-line.

UVM Perkins Geology Museum, Perkins Hall, 2003 view. Photo by Thomas Visser

Perkins Hall Geology Department lab, 2003 view. Photo by Thomas Visser Two years later the UVM Perkins Geology Museum and the UVM Geology Department were moved to Delehanty Hall on UVM's Trinity Campus. Since the museum’s move, Perkins Hall has undergone renovations, one in 2017 for lab and classroom space, and one in 2019. During the 2019 renovation, the Champlain Thrust Fault oil painting was discovered behind a false wall- originally there to protect it. During the 1992 renovation, a false wall was constructed to protect and preserve it.15 While Perkins Hall no longer houses the prestigious geology collection, there are still stories being told, both old and new that are associated with the history of the UVM Perkins Geology Museum and the UVM Geology Department, which in 2021 was proposed to be merged with the UVM Geography Department.

Perkins Hall, 2021 view looking south. Photo by Erin Briggs Notes1. ”UVM Geology Department Gathers in One Building for This Year,” Burlington Free Press (1964), 17. 2. Ibid. 3. “About Us,” The University of Vermont Perkins Museum of Geology website, accessed Sept. 19, 2021, http://www.uvm.edu/perkins/about-us. 4. Ibid. 5. “Perkins Geology Building,” Public Relations Office, The University of Vermont, 1964, University of Vermont Special Collections, Burlington, VT. 6. Ibid. 7. “About Us,” The University of Vermont Perkins Museum of Geology Website, accessed Sept. 19, 2021, http://www.uvm.edu/perkins/about-us. 8. Ibid. 9. Ibid. 10. Nancy Bazilchuk, “Grand Canyon Makes Way for Progress,” Burlington Free Press (1992). 11. Ibid. 12. Ibid. 13. Tom Hacker, “Geology Museum Hits Budget Crunch,” Burlington Free Press (1994). 14. Ibid. 15. “New Exhibits and Specimens,” The University of Vermont Perkins Museum of Geology website, accessed Nov. 5, 2021, https://www.uvm.edu/perkins/new-exhibits-and-specimens |

|

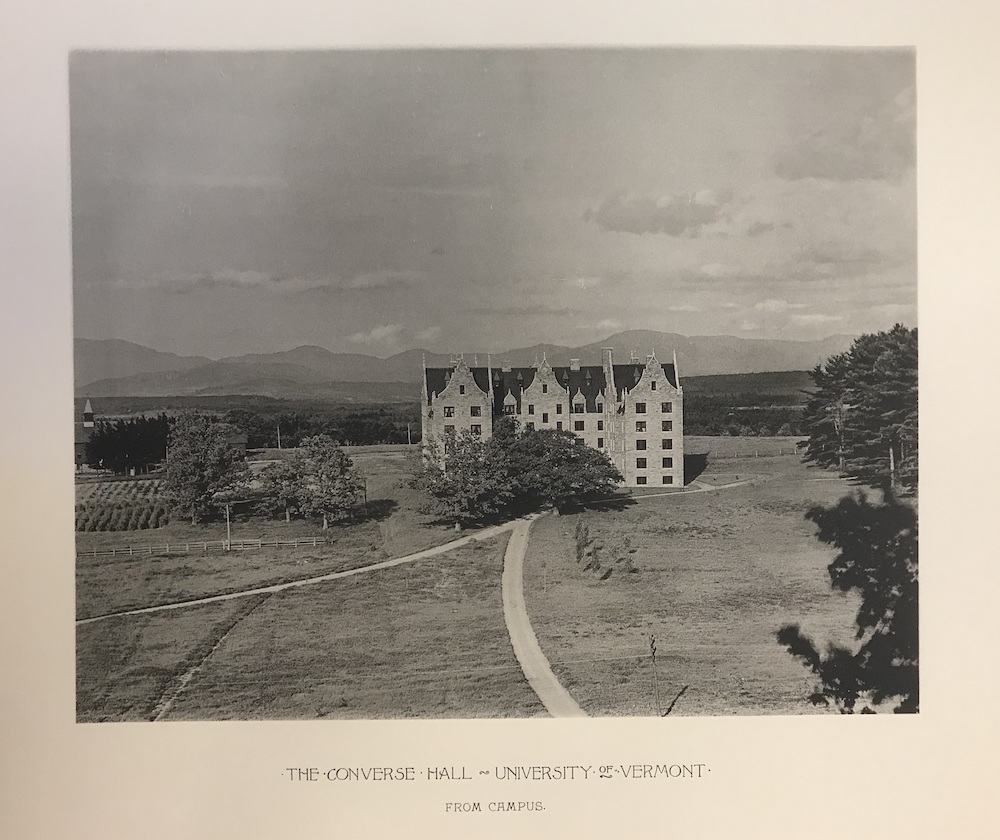

Converse Hall (1895)Designed by the Wilson Bros. firm of Philadelphia and erected in 1895, Converse Hall is the University of Vermont’s oldest standing purpose-built dormitory. Constructed of Rutland marble at the cost of $125,000, this imposing Chateauesque building originally stood in an open field on the eastern edge of campus, with the university’s experimental farm to its north.1 Though depicted in a picturesque rural landscape in promotional material, the building was intended to vanguard the eastward expansion of campus. From 1881-1907, UVM president Mathew Buckham embarked on a campaign of extensive alumni-funded building projects. John H. Converse, train magnate and Vermont alumnus, donated generously toward the construction of Converse Hall, as well as the Converse Cottages and Williams Science Hall—also designed by the Wilson Bros.2

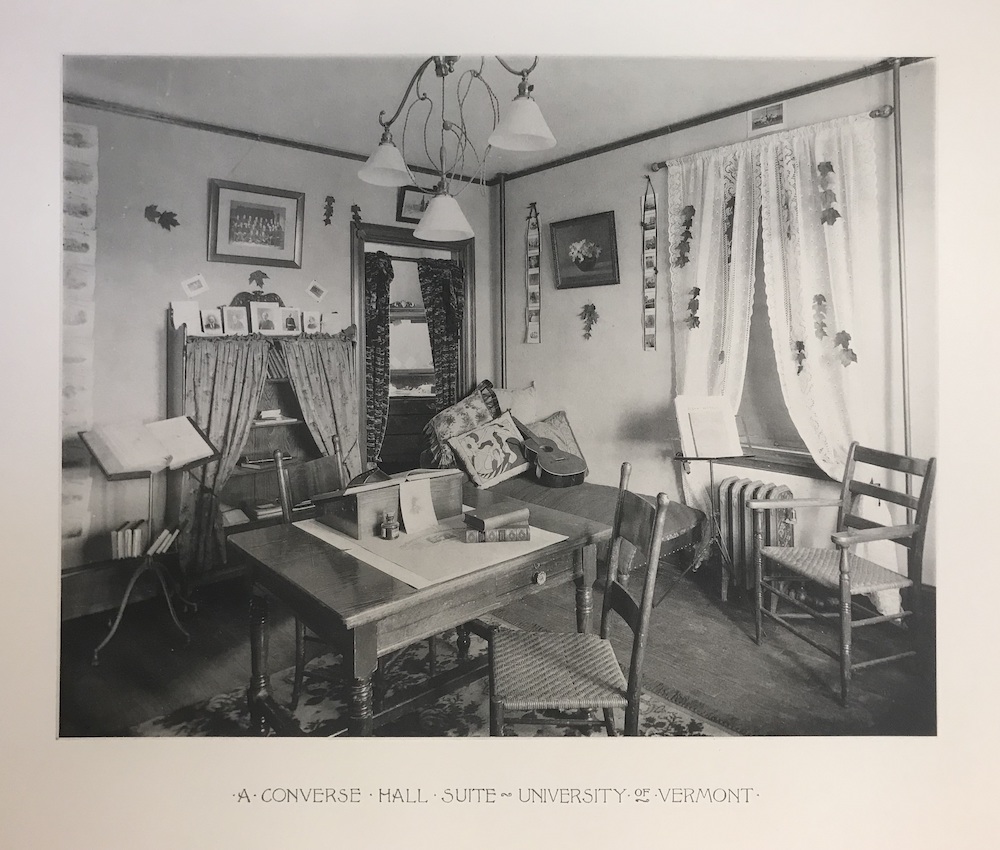

"The Converse Hall." From The Williams and Converse buildings, the University of Vermont (Heliotype Printing Co., circa 1895.) In addition to his contributions to the campus, Converse established a scholarship fund and public debate prize for UVM students.3 Over the decades the building has undergone two major interior renovations, the first carried out by the WPA from 1938-1939, and the second between 1974 and 1975. Although the dorm’s living spaces have changed significantly, extant images, blueprints, and the well-preserved interiors of the former Converse Cottages provide clues to what this early student housing may have looked like. When the building opened to students in 1895, a reporter for the Burlington Free Press described Converse Hall as “A Veritable Palace,” and “one of the handsomest and best furnished college dormitory buildings to be seen on the American continent.” Prior to the 1974 renovation the dorm boasted a gym, a dining hall, and study rooms with fireplaces. The dormitory was intended to foster a sense of community among residents, who would form a number of clubs and sports teams in the early years of the dorm.4

"A Converse Hall Suite." From The Williams and Converse buildings, the University of Vermont (Heliotype Printing Co., circa 1895.) Originally male-only, Converse Hall became coed in 1970.5 At various points in its history, Converse served other functions; including as a barracks and drill yard during both World Wars,6 and a temporary homeless shelter during the summer of 2000—hosting twenty families over two months.7 In its early years, the dorm also hosted faculty and staff. In 1917 a scandal broke out when two German residents, a professor and a janitor, moved out in response to the garrison of army signalmen. Although the two-faced suspicion and antagonism from locals, both the University and Signal Corps officers vouched for their loyalty.8 The building’s outward appearance, dark interior, narrow repetitive halls, creaky noises, and empty attic lend this “Veritable Palace” an eerie quality to some students. An oft repeated ghost story alleges that the building is haunted by the spirit of a medical student named Henry who hanged himself in the 1920s. Since at least the 1980s, residents have reported flickering lights, mysteriously falling objects, and doors that slam shut on their own.9 No such incident, however, seems to appear in campus records or local newspapers. While the building is beloved by students and alumni and has achieved listing on the National Register of Historic Places, halls of repetitive rooms which have replaced the original communal spaces and warmly furnished interiors with create the feeling of of a building haunted by impressions of its past.

Converse Hall, view looking east, 2021. Photo by Thomas Visser Notes1. Charles Edwin Allen, About Burlington Vermont (Hobart J. Shanley & Company, Burlington, VT, 1905), 44. 2. Paula Sagerman. “Converse Hall at the University of Vermont,” National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form, Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service. December 2016. 3. “John Herman Converse,” Cassier’s, New York, NY. v. 20, May-October 1901. 4. Sagerman. 5. Stuart Perry, “Contrast,” Burlington Free Press, November 5, 1971. 6. “Converse Hall a Barracks.” Burlington Free Press, September 18, 1917.; “New Life for Old Converse.” Vermont Alumnus. v. 22 No. 1, October 1942, 10. 7. University of Vermont. Vermont Quarterly, University of Vermont: Summer 2000, July 27, 2000, 13. 8. “Appelman Not Ousted.” Burlington Free Press, October 11, 1917. 9. Susan Green, “The Haunting of Converse Hall,” Burlington Free Press, October 30, 1983. |

|

UVM Gymnasium / Royall Tyler Theatre (1901 / 1973)By Brooke TalbottThe Royall Tyler Theatre that students, faculty, and Vermonters know today ultimately owes its existence to a “providential fire” which destroyed the university’s “ramshackle gymnasium” in 1886.1 According to an edition of The University Cynic from 1886, a scene of “jubilation” was seen among students as the building went down in flames, leading to questions of whether the fire was incendiary and possibly set by students.2 No matter the cause, the fire ultimately set the university on the path towards the creation of the Royall Tyler Theatre. Currently located at 116 University Place, the structure has gone through many phases over the past one hundred and twenty years. In 1888, complaints from students and faculty about the lack of “physical culture” facilities reached a climax, resulting in President Matthew Henry Buckham’s allocation of $20,000 for a “very plain gymnasium.” 3 In 1900, a site next to UVM's Old Mill building was selected and the architectural firm of Andrews, Jacques, and Rantoul was chosen to create the gymnasium’s plans. These architects were pupils of H. H. Richardson, one of America's most famous architects who had designed UVM's Billings Library. As a result, they would be more than capable of creating a structure which was harmonious with other campus buildings. Construction of the gymnasium began in April 1901; by the end of construction, total costs had reached thirty thousand dollars, an amount which was raised through subscriptions of alumni, faculty, and students. The first public exhibition of the new gymnasium was held from October 14-16, 1901 and featured the Boston Symphony Orchestra. The new structure created a home for students and faculty to engage in physical activities, military drill, dances, Kake Walks, commencement, and musical programs.4

Front of UVM Gymnasium, circa 1930s. Photo courtesy of UVM Special Collections.

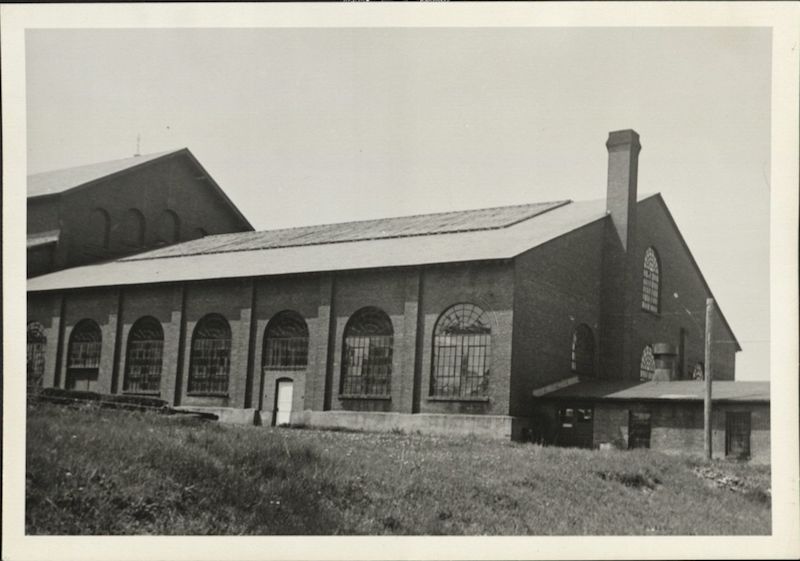

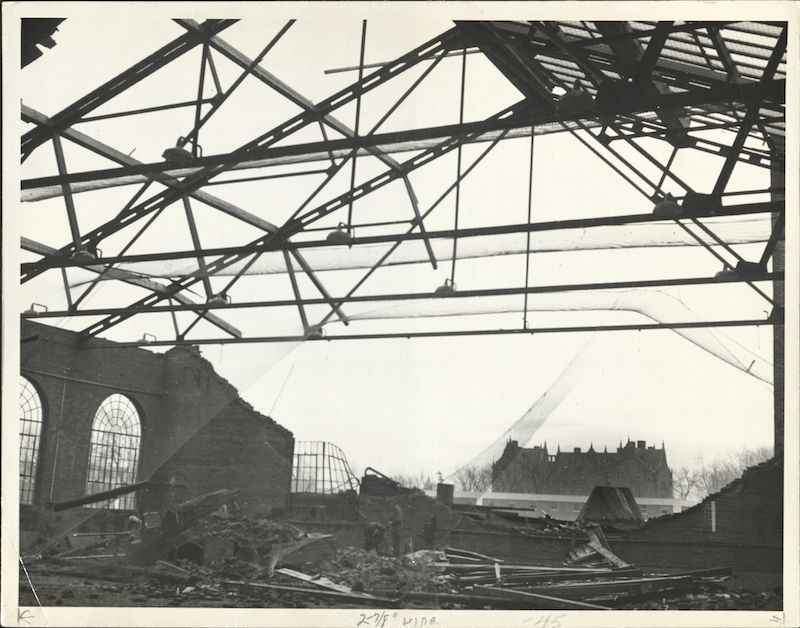

Front, west elevation of Royall Tyler Theatre. Photograph by Brooke Talbott, October 2, 2021. By 1911, however, the gymnasium’s ability to act as a drill hall was no longer feasible. As a result, a glass-roofed structure, known as “The Cage” was erected at the back of the building. Construction for the new structure was begun in May 1911; the structure measured 120 feet by 100 feet, with concrete foundations, a slate roof and steel trusses, rendering the building fireproof. It was lit by a skylight on the south side of the roof, measuring 90 feet by 30 feet, and was steam heated.5 The Cage served as a baseball cage and a drill hall for the University Battalion. Along with these two main functions, the Cage also acted as an assembly and concert hall into the 1940s.6 In November of 1950, the roof of the Cage was completely blown off by a storm. The Cage resembled a “bombed out building,” with damages estimated to be $150,000.7 By June 30, 1951, however, repairs to the building were complete. Repairs were completed entirely by the UVM maintenance department.8

Inside The Cage, circa 1911. Photo courtesy of UVM Special Collections.

Outside The Cage, facing north, circa 1911. Photo courtesy of UVM Special Collections.

Ruins of The Cage. The partially crumpled north side wall can be seen on the left. The roof is almost entirely blown off. November 28, 1950. Photo courtesy of UVM Special Collections. Around this time, the University’s physical education program outgrew the gymnasium, and the building was subsequently used for offices, classrooms, and support facilities. In March of 1963, UVM Dean of Administration Lyman S. Rowell drew up plans to add classrooms, office, storage, and workspace by dividing the old gym.9 The Military Science Department, housed in the building, was set to receive three new classrooms, as well as storage space for uniforms on the east side of the gym. The rest of the gym was to be converted to office space, a film library and two projection rooms for the audiovisual department. The director of student housing and the campus security office were also set to receive space in the gym. In 1969, the old gymnasium took its final steps toward becoming the structure that exists on campus today. By this point, the university needed a facility to house its fine arts departments. However, due to a lack of funding available, the university was not able to build a new structure. As a result, Director of Theatre Edward J. Feidner successfully revived a previous proposal in 1973 to rehabilitate the old Gymnasium into a new theatre with an innovative thrust stage. Feidner’s idea allowed a historic campus structure to be preserved and put to good use, all while saving money. Along with the theatre itself, the Royall Tyler Theatre today contains a box office, marketing office, classrooms, and faculty offices.10

Royall Tyler Theatre conversion, 1973. Photo courtesy of UVM Special Collections

Royall Tyler Theatre conversion, 1973. Photo courtesy of UVM Special Collections The Royall Tyler Theatre earned its name from a Bostonian turned Vermonter.11 Royall Tyler was born to Royall and Mary Steele Tyler on July 18, 1757, in Boston. After graduating from Harvard in 1776, Tyler read law with Francis Dana of Cambridge, Benjamin Hichborn of Boston, and possibly with Oakes Angier. Tyler was admitted to the bar on August 19, 1780. He began his practice in Falmouth, Maine, but returned to Boston to practice from 1782 until 1790. In 1787, two events occurred which would ultimately lead to the eventual naming of the Royall Tyler Theatre. In February 1787, Tyler came to Vermont for the first time while in pursuit of Daniel Shays and his band. Although Tyler was not able to extradite the band, his convincing argument caused the Council to deny any further aid to the insurgents. After his trip to Vermont, Tyler was sent to New York City, where he attended a performance of The School for Scandal. Tyler was so inspired by the play that he spent the following weeks creating a play of his own. Tyler’s play, The Contrast, premiered at the John Street Theatre in New York on April 16, 1787. Tyler’s literary career did not stop here; he wrote multiple other plays, novels, essays, and poems, and later remained active in Vermont literary circles. In 1791, Tyler moved to Vermont. From 1794-1801, he served as a state’s attorney; from 1801-1807, he served as a Justice of the State Supreme Court; from 1807-1813, he served as Chief Justice of the State Supreme Court; and from 1815-1822, he served as Register of Probate for Windham County. Tyler also served as a trustee of the University of Vermont from 1801-1813, received an honorary master’s degree in 1811, and was a professor of jurisprudence from 1811-1814.12 Tyler’s contributions to the university and state of Vermont ultimately led to the theatre being named in his honor. While the origins of the theatre’s name appear to stem from an honorable man, some of the events which took place within its walls were anything but. One such event, a much-beloved campus tradition for decades, was the Kake Walk.

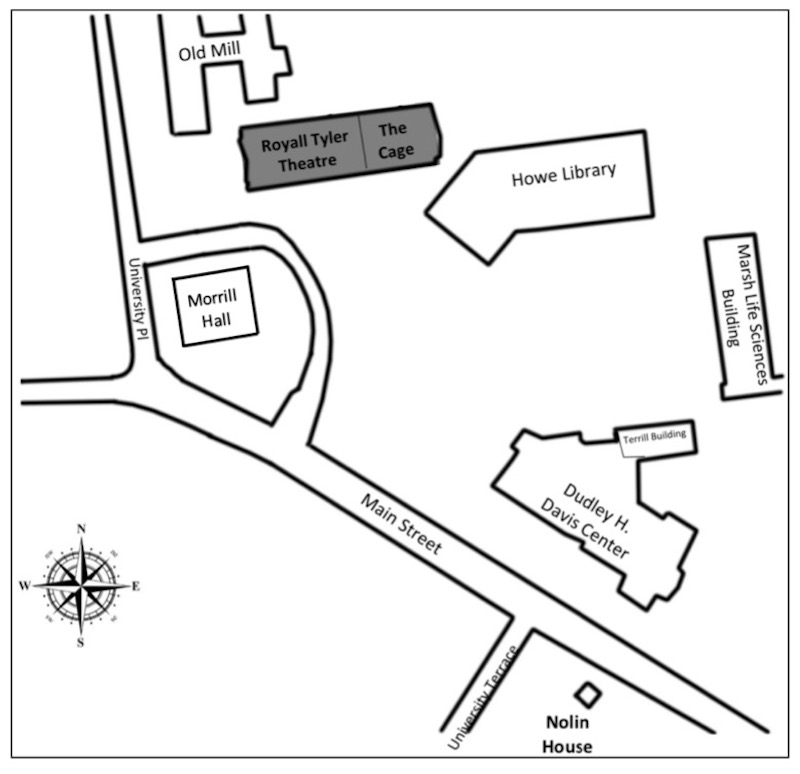

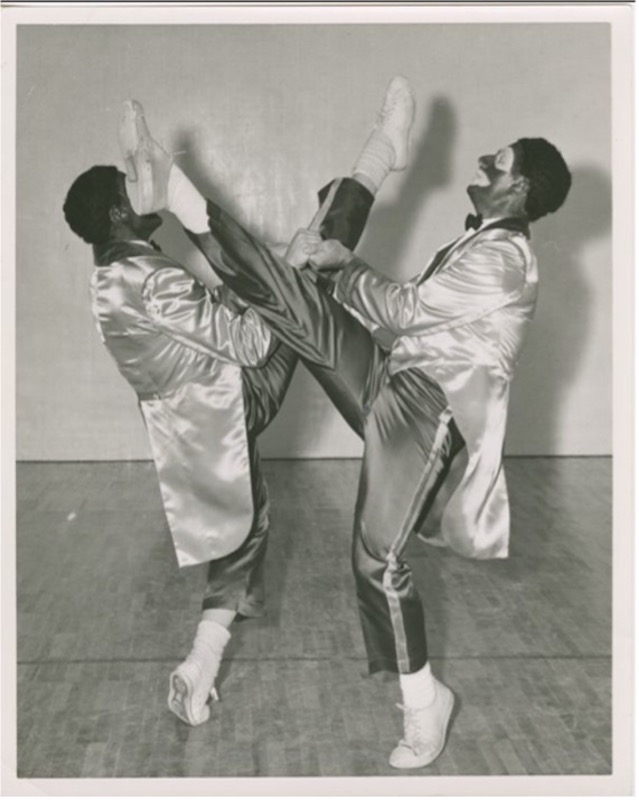

Partial map of UVM campus showing the Royall Tyler Theatre and The Cage. Both structures are shaded. Map made by Brooke Talbott. The origin of the University of Vermont’s Kake Walk dates back to the 1890s. While the origins of UVM’s first Kake Walk are somewhat unclear, it is believed to have begun in 1894 in a men’s residence hall as a “spontaneous bit of horseplay” after a military ball had been canceled. 13 When the Kake Walk first began, it resembled American minstrel shows, a form of entertainment which featured white performers who blackened their faces with burnt cork.14 These performers caricatured African Americans through song, dance, stories, and stand-up comedy. Characters generally featured the “uncultured, parochial, happy-go-lucky southern plantation slave (Jim Crow) in his tattered clothing, or the urban dandy (Zip Coon or Dandy Jim), frequently presented as slow-talking, mischievous and gaudily overdressed.”15 Along with being dim-witted and lazy, both characters were always fond of watermelon and chicken. The “cakewalk” dance, which was a standard act in minstrel theatre, originated on plantations as a competition between slaves.16 The pair of slaves who most entertained white owners would be rewarded with cake. The University of Vermont’s Kake Walk took on a life of its own, however, creating its own traditions and becoming one of UVM’s most anticipated events each year. Early Kake Walks at UVM occurred during the Winter Carnival weekend, which took place over a weekend in February each year.17 Preparations for the event took place year-round; the entire event was directed by three senior men, four junior men, and one female student appointed as secretary. While the “a walkin’ fo’ de kake” competition was the main event of the weekend, the overall event also included stunts, a peerade, and skits.18 In the 1930s and 1940s, the event added the election of the Kake Walk King and Queen. By the 1960s, the three-day festival had evolved to include a ball, jazz concert, winter sporting events, and ice sculpture competitions. Until 1965, the “walkers,” the performers who completed the Kake Walk dance, came from the sixteen campus fraternities.19 Each Kake Walk performance starred pairs of men dressed in costume and wearing blackface; until 1916, one of the men dressed in drag. Each pair competed in a “strenuous display of kicking, strutting, and fancy stepping that gives premium points to the height of the kick and coordination of each pair as a team.”20 The walking was done in colorful costumes, known as “silks,” to the tune of “Cotton Babes.”21 While the event was extremely popular from its inception, by the 1960s its popularity reached a climax as the “cheers of about 8000 students, alumni and residents of the area who jam the University’s Patrick Gymnasium” could be heard.22

Kake Walkers dressed in blackface, most likely dressed as plantation slaves, 1927. Photo courtesy of UVM Special Collections.

Practicing Kake Walkers, dressed in silks, wearing blackface, 1963. Photo courtesy of UVM Special Collections. According to Professors James Loewen and Larry McCrorey, the earliest instance of opposition to the Kake Walk occurred in 1954 when Phi Sigma Delta refused to wear blackface.23 In 1963, the Interfraternity Council eliminated blackface and replaced it with light green makeup; disrespectful dialect was still used. In 1964, the makeup was changed to dark green as a response to audience complaints. Finally, in 1969, Kake Walk was officially removed from the Winter Carnival weekend.24 The removal of the long-beloved tradition was met with an extremely negative reaction from alumni. Following the decision to discontinue the Kake Walks, alumni flooded the University President with letters and phone calls expressing their discontent. On October 27, 1969, Edgar M. Weed, an alumnus of UVM, stated in a phone conversation that he was concerned that a group of “Johnny-come-lately professors” were getting the chance to speak out against the Kake Walks in the media while the opinions of alumni were ignored.25 He went as far as to warn that he would be rounding up a few “influential businessmen” from the northeast to go speak to President Rowell. John J. Zellinger, M.D., another alumnus, went even further with his expressions of anger.26 In a letter addressed to the head of the alumni council, Zellinger challenged the campus to “name [him] one instance where the black race has been treated anything less than equal, if not better at times, than the other students at the University.”27 These are just two examples of a large collection of correspondence which occurred after the discontinuation of the Kake Walks. While each account expresses slightly different forms of anger or annoyance, each letter or phone call mentions the discontinuation of funding for the University, revealing just how deeply the Kake Walks were ingrained in the identity of the University of Vermont. In February 1970, however, the Kake Walks returned to the UVM campus for a final hurrah. On Sunday, February 15, a group of around five hundred students gathered in Simpson Hall cafeteria to watch the “spontaneous” walking of “clean-faced fraternity men” who reportedly rapidly organized into teams.28 After the fifth team, Tau Epsilon Pi, completed their routine, a group of black students from St. Michael’s College walked onto the floor; one student stated that “if there’s going to be any walking done here tonight, it’ll be over my dead body.”29 While the group of around eight to ten black protesters, accompanied by a few white protesters, stood their ground, chants ranging from “No trouble, no trouble!” to “We want Kake Walk” could be heard throughout the cafeteria.30 The current Interfraternity Council President, Sandy Luckenbill, attempted to intervene, claiming that the event was an attempt to determine if a non-racist event could be held. Protesters responded by informing Luckenbill that a non-racist Kake Walk did not exist. The students were eventually ushered out into the yard of Simpson Hall by campus security, where yet another team of Kake Walkers attempted to complete their walking routine. This routine was stopped by a black protester who “ran the team down and halted the routine, assisted by club-armed friends.”31 After tense exchanges between protesters and students, the incident died down and all students dispersed. In the following weeks, however, opinions from UVM alumni and students regarding the discontinuation of the Kake Walks were, once again, made clear. While University President Rowell expressed his concern regarding an off-campus group threatening violent interruption, Governor Davis referred to the incident as “unfortunate.”32 Kappa Sigma President, Art Williamson, stated that he and his brothers believed that Kake Walk was “not at all racist” and that they would actively participate in petitioning, supporting and debating the restoration of the Kake Walks.33 Meanwhile, Bernie Fineburg, the former director of Kake Walk, stated that the directors remained steadfast in their decision that the Kake Walk should remain permanently discontinued. This incident further confirms this deeply entrenched UVM tradition, one which most likely remained entrenched for generations to come. Notes1. “The Royall Tyler Theatre,” UVM Theatre Handbook, 46, https://www.uvm.edu/sites/default/files/Department-of-Theatre/rtthistory.pdf. 2. The University Cynic, 1886. 3. “The Royall Tyler Theatre,” UVM Theatre Handbook, 46, https://www.uvm.edu/sites/default/files/Department-of-Theatre/rtthistory.pdf 4. Ibid. 5. “New Baseball Cage,” UVM Notes, Vol. 2 No. 2-3 (1911). 6. “The Royall Tyler Theatre,” UVM Theatre Handbook, 46, https://www.uvm.edu/sites/default/files/Department-of-Theatre/rtthistory.pdf. 7. The Burlington Free Press (November 28, 1950): 16. 8. “UVM Maintenance Dept. Completes Repairs to Gym,” The Burlington Free Press (30 June 1951): 12. 9. “Old UVM Gym Remodeling Set,” The Burlington Free Press (20 March 1963): 11. 10. Ibid. 11. C.A. Tillinghast, “Biographical Sketch of Royall Tyler,” 1-2. 12. Ibid. 13. Lee Alan Prosnit and Richard Alan Fain. “Kake Walk History,” Special to The New York Times (12 December 1967): 1. 14. “Minstrel Songs,” The Library of Congress Celebrates the Songs of America: Minstrel Songs, The Library of Congress, accessed 1 October, 2021, https://www.loc.gov/collections/songs-of-america/articles-and-essays/musical-styles/popular-songs-of-the-day/minstrel-songs/. 15. Ibid. 16. Kake Walk at UVM, University of Vermont Libraries Digital Collections, accessed 1 October 2021, https://cdi.uvm.edu/collection/uvmcdi-uvmcdikakewalk. 17. Lee Alan Prosnit and Richard Alan Fain. “Kake Walk History,” Special to The New York Times (12 December 1967): 1-2. 18. Kake Walk at UVM, University of Vermont Libraries Digital Collections, accessed 1 October 2021, https://cdi.uvm.edu/collection/uvmcdi-uvmcdikakewalk. 19. Prosnit, Lee Alan and Fain, Richard Alan. “Kake Walk History,” Special to The New York Times (12 December 1967): 1-2. 20. Ibid. 21. Ibid. 22. Ibid. 23. Kake Walk at UVM, University of Vermont Libraries Digital Collections, accessed 1 October 2021, https://cdi.uvm.edu/collection/uvmcdi-uvmcdikakewalk. 24. Ibid. 25. Edgar M. Weed, Jr. to Mr. W.N. Cogswell, October 27, 1969, The University of Vermont Alumni Office, The University of Vermont Libraries, Special Collections. University Archives, Record Group 53: Fraternities and Sororities, Series: Kake Walk. 26. John J. Zellinger to Mr. David T. Washburn, December 26, 1969, Kake Walk at UVM, The University of Vermont Libraries, Special Collections. University Archives, Record Group 53: Fraternities and Sororities, Series: Kake Walk. 27. Ibid. 28. Chris Hapner, “Black Students Break Up Spontaneous ‘Kake Walk’,” The Burlington Free Press (16 February 1970): 1. 29. Ibid. 30. Ibid. 31. Ibid. 32. Fred Stetson, “Kake Walk Condemned, Supported.” The Burlington Free Press (17 February 1970): 11. 33. Ibid. |

|

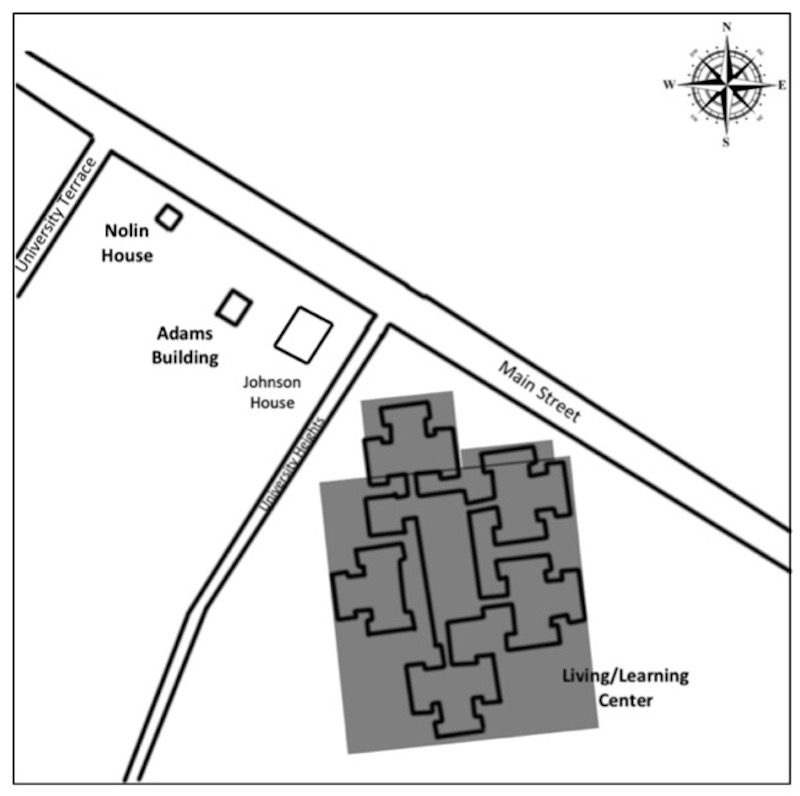

Adams Building (1905)By Brooke TalbottThe Adams Building, currently situated at 601 Main Street, has gone through many phases over its one hundred- and sixteen-year history. Its origins began on April 17, 1905, when the University of Vermont and State Agricultural College (UVM) gave a piece of land to the United States Government to be used for a Weather Bureau building. In the event that the Weather Bureau moved its station, the structure at 601 Main and any other buildings erected on the plot of land would revert to the university. Once the land transfer was completed, the U.S. Government hired Harding and Upman, Architects of Washington, D.C. to design the building.1 Since its construction, the exterior of 601 Main Street has remained largely unchanged. Rectangular in shape, the structure is made almost entirely of brick, with two stories and a basement level. The northeast side of the building, which faces Main Street, has three windows across the second floor and two windows on the first; the first-floor windows are separated by the front porch, which is perfectly centered. The front porch is the first thing passersby notice, as it is covered by a large, white, Roman Doric order portico with two columns on each side. Another noticeable feature of the building is the roof, which is lined with a white cornice and topped with a baluster. The northwest and southeast sides of the building share these characteristics; the major difference is that these sides contain four windows on each floor.2

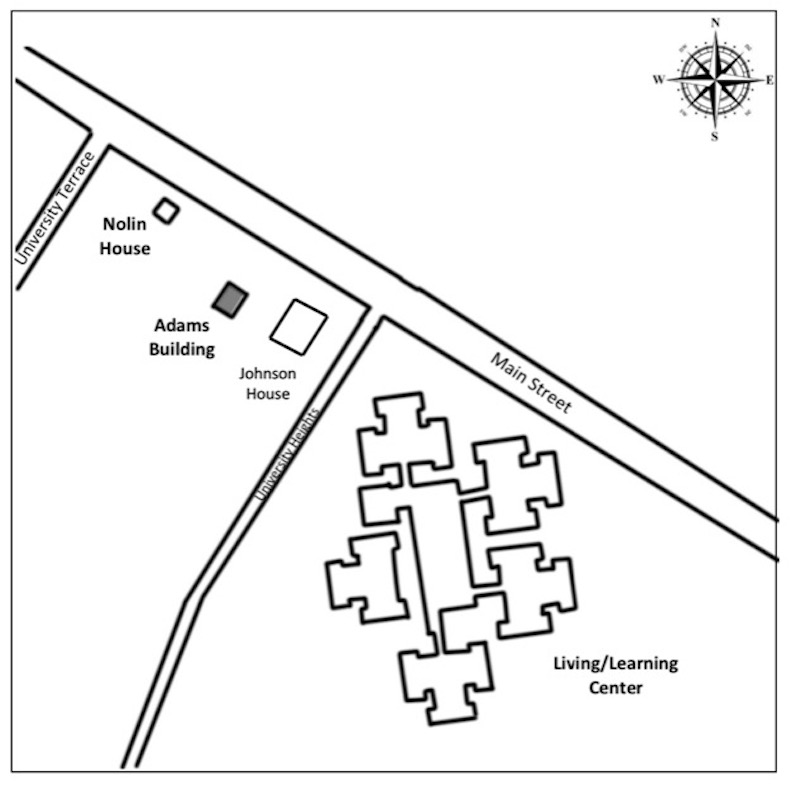

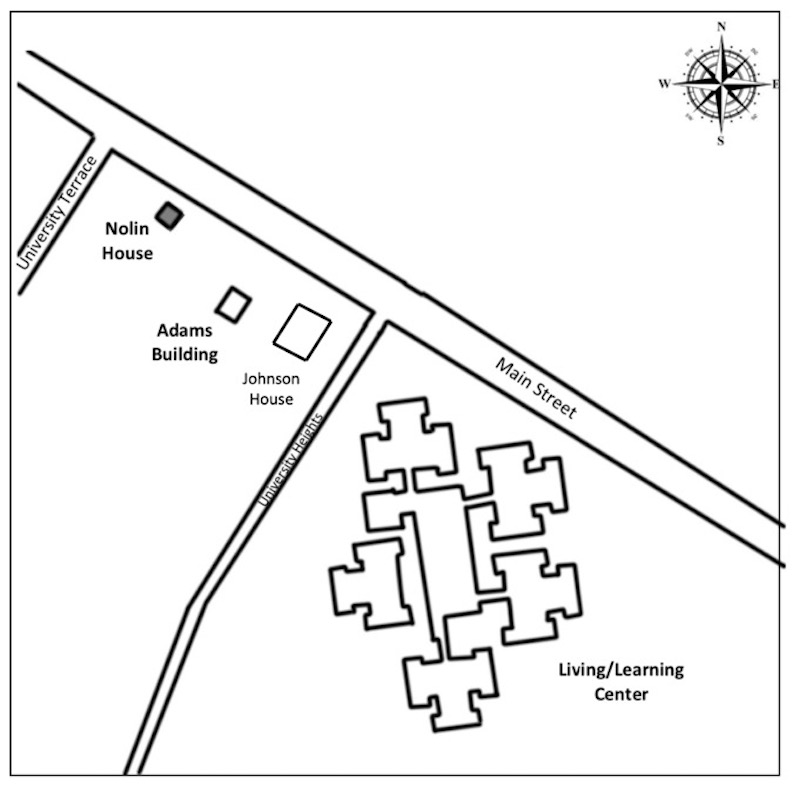

Partial map of UVM campus. Adams Building is shaded, located between Nolin House and Johnson House. Map made by Brooke Talbott In 1905, the address of the Adams Building was not 601 Main; instead, it was 489 Main Street.3 Multiple occupants occupied the structure, a theme which carries through the majority of the structure’s life. Along with the U.S. Weather Bureau, J. William Votey, listed as a professor of Civil Engineering at UVM, occupied the building and most likely worked with the Weather Bureau. By 1910, Votey was joined by two other occupants, Cassius Peck and Amos Morrill, both presumed to be meteorologists.4 In 1930, the building address changed again; at this point, the address was listed as 91 Williston Road.5 Along with the U.S. Weather Bureau, the occupants of the building were the UVM Farm, the University Service Station, Fred C. Fiske, and Milton W. Dow. Fiske is listed as a farmer and Dow is listed as a meteorologist with the U.S. Weather Bureau. By 1943, the Weather Bureau had relocated to the Burlington Airport in order to assist with moving war-related planes in and out of Burlington.6

Adams Building, front elevation, 2021. Photo by Brooke Talbott While meteorologists continued to live in the building, they no longer performed functions of the Weather Bureau within its walls. As a result, by 1945, UVM wanted to reacquire the property. Consequently, the university hired attorney Louis Lisman, who wrote a letter to the Government reminding them of the provisions of the original deed to the property. The provisions, mentioned above, required that the building be returned to the university. In October of 1951, the land reverted to UVM. In 1951, the address of the building is finally listed as 601 Main Street, with its only occupant being Milton W. Dow.7

Aerial view of UVM. Adams Building can be seen towards the bottom right corner. Photo taken in 1927 by Fairchild Aerial Services. Photo courtesy of UVM Special Collections. From 1951 to 1961, 601 Main Street acted as the Military Science Building, housing the Air Force R.O.T.C. unit.8 In a renovation costing between $3000 to $5000, the Military Studies program altered the interior of the building in order to create office and classroom space for the department. In 1961, the Military Studies department left the building. As a result, the Military Science Building became the home of the Pringle Herbarium. Although many proposals were made to alter the building in order to better fit the needs of the herbarium, the building remained virtually unchanged during the herbarium’s fourteen-year occupation. In the summer of 1975, the herbarium moved out of the building, due to the need for more space. After the Pringle Herbarium moved out, a division of the UVM Department of Natural Resources moved in. While many alterations to the interior of the building were made during the division’s occupancy, a major change occurred to the exterior of the building. In 1977, the back porch was demolished, and a modern-looking elevator tower was built in its place. In 1983, the building reverted to the Military Science department, which remained until 1989.9 In 1989, the Department of Natural Resources returned to the building, where they remained until around 1997.10 Upon the department’s reoccupation of the building, the name of the building was changed to one which students, faculty, and community members of today would recognize: the Adams Building. The name stemmed from Thurston Madison Adams, an Agricultural Economist who worked at UVM from 1943 to 1961 and “provided long and significant service to agriculture in the state of Vermont and in the New England region through his continuous efforts in the development of regional milk pricing.”11 Around 1997-1998, the Agricultural Experiment Station moved into the building, where it remained until 2007-2008.12 In 2007-2008, the Military Studies program was again listed at 601 Main Street, where it remains in 2021.13 Currently, the structure at 601 Main Street houses the university’s Army ROTC program. Although the building at 601 Main Street has seen many occupants over the past hundred years, the structure has remained steadfast as an integral corner of the university. Notes1. Erin Hammerstedt, “History of 601 Main Street,” UVM Campus Treasures, The University of Vermont, December 1999, http://www.uvm.edu/~campus/601main/601mainhistory.html. 2. Ibid. 3. Burlington City and Winooski Directory, L.P. Waite & Co., Publishers, 1905. 4. Burlington City and Winooski Directory, L.P. Waite & Co., Publishers, 1910. 5. Manning’s Burlington, Winooski and Essex Junction Directory, H.A. Manning Co., 1930. 6. Erin Hammerstedt, “History of 601 Main Street,” UVM Campus Treasures, The University of Vermont, December 1999, http://www.uvm.edu/~campus/601main/601mainhistory.html. 7. Manning’s Burlington, Winooski, South Burlington and Essex Junction Directory, H.A. Manning Company, 1951. 8. Erin Hammerstedt, “History of 601 Main Street,” UVM Campus Treasures, The University of Vermont, December 1999, http://www.uvm.edu/~campus/601main/601mainhistory.html. 9. Ibid. 10. UVM Directories, 1997/1998 – 2006/2007. 11. Erin Hammerstedt, “History of 601 Main Street,” UVM Campus Treasures, The University of Vermont, December 1999, http://www.uvm.edu/~campus/601main/601mainhistory.html. 12. UVM Directories, 1997/1998 – 2006/2007. 13. UVM Directories, 2007-2008. |

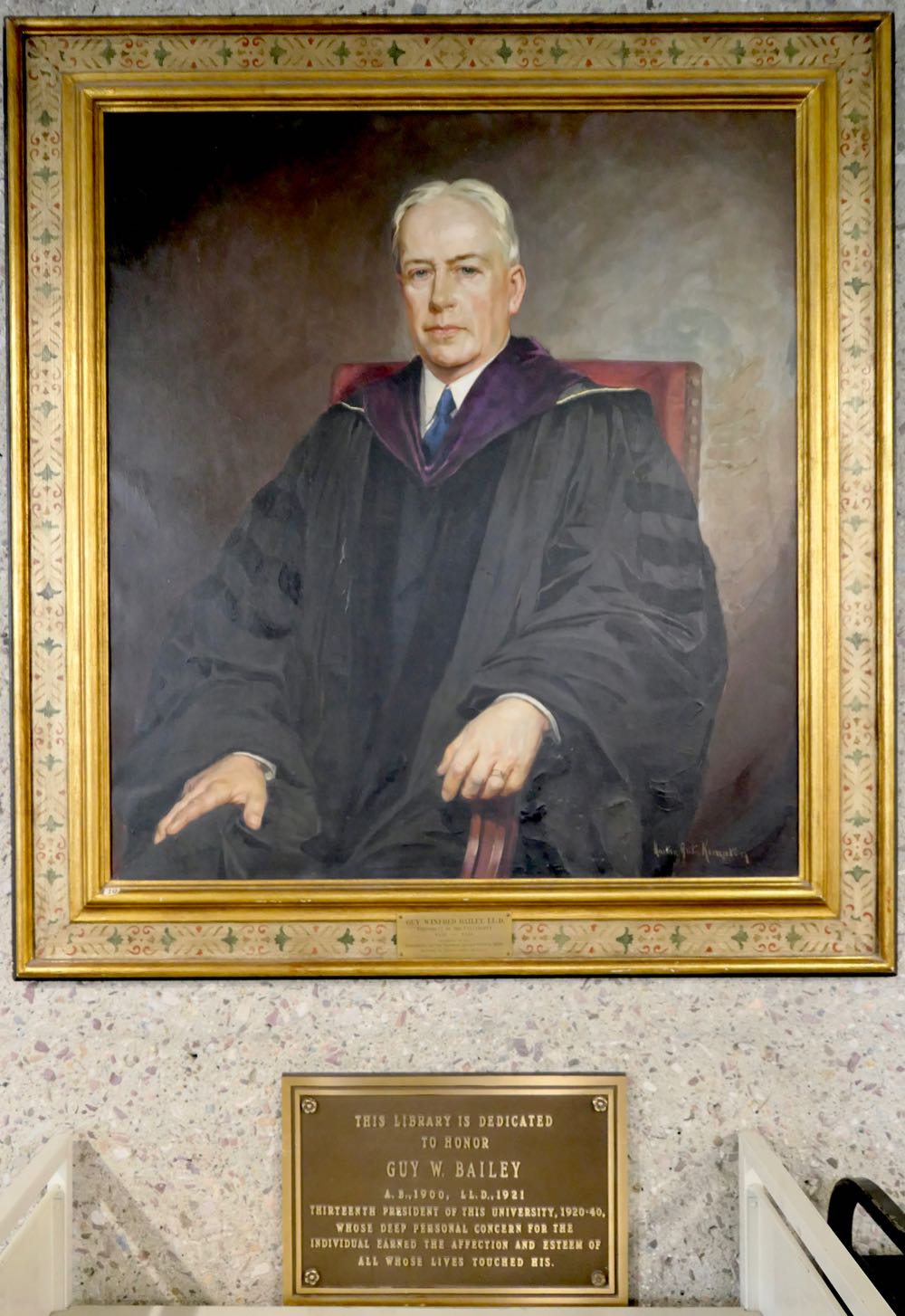

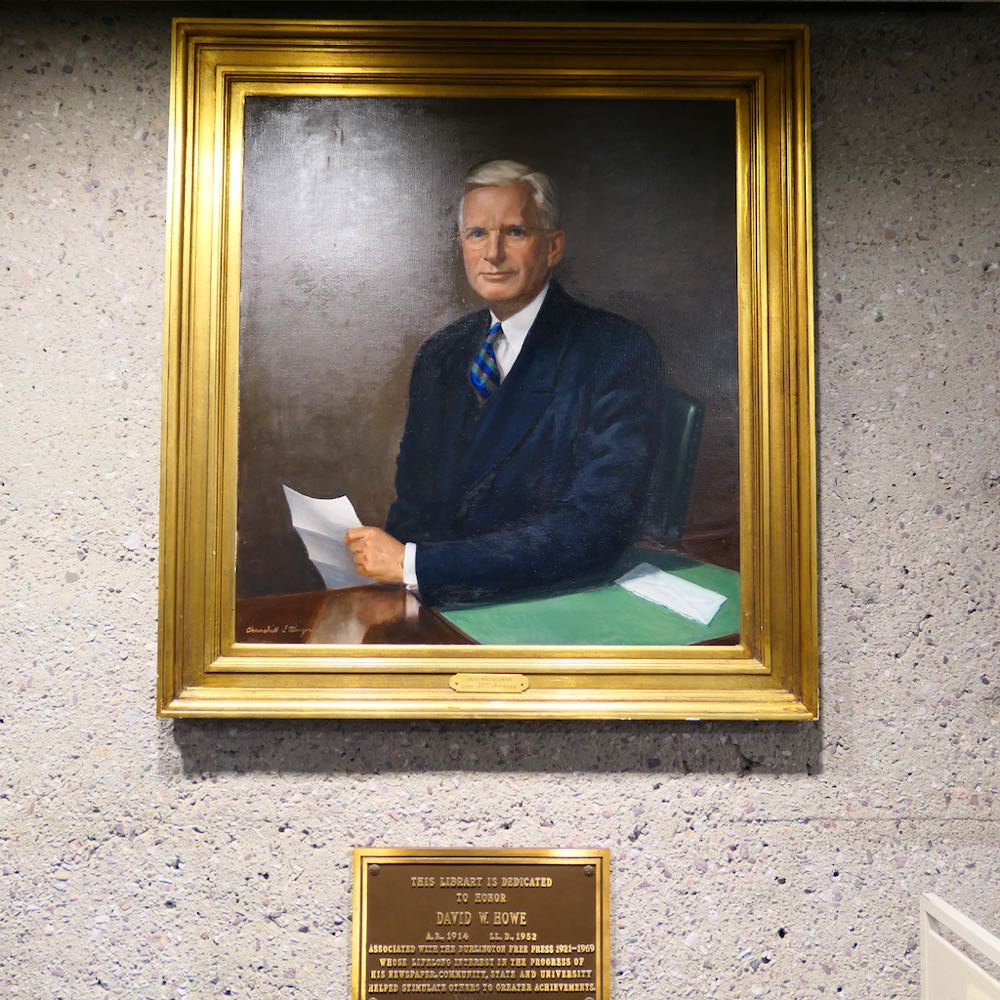

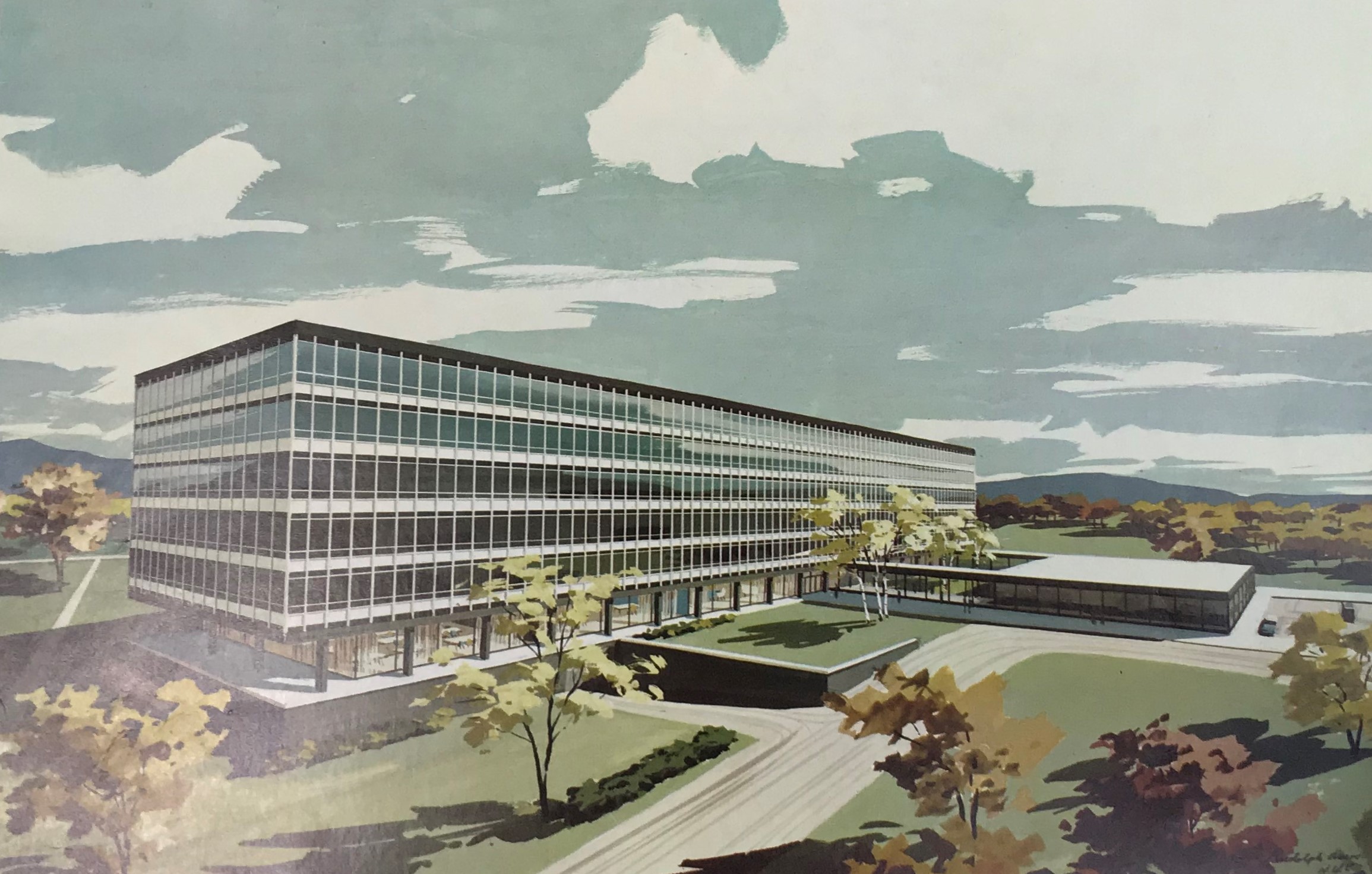

Robert Hull Fleming Museum (1931)The history of the Fleming Museum Collection stretches back over a hundred years before the building opened its doors in 1931. In 1826 a self-described College of Natural History, formed by University of Vermont faculty and interested members of the public, established a collection in the Old Mill Building “for the acquisition and diffusion of knowledge in every department of natural history, and the accumulation of all materials natural and artificial which can advance these ends.”1 In keeping with museums of the day and the constraints of the small, ragtag collection, the first museum resembled a “cabinet of curiosities,” featuring local artifacts, Middle Eastern relics, and a collection of dead animals.2 In 1862 the burgeoning collection was relocated to the new library building, Torrey Hall, where it remained until 1931, eventually taking over the entire building.3 The museum is named for Robert Hull Fleming, a shipping merchant, life member of Art Institute of Chicago, and UVM alumnus. Fleming’s niece and sole heir, Katherine Wolcott, contacted UVM president Guy Bailey with an offer to donate funds for a museum named in her uncle’s honor. Bailey, in fact, was already considering building a new museum and had blueprints from architect William Kendall of the firm McKim, Mead, and White. Donating $150,000, Wolcott remained involved throughout the process and had final say over the building’s design and name; which she shortened from the Robert Hall Fleming Museum of Art. Vermont Philanthropist James B. Wilbur offered up his art collection as well as an additional $100,000 on the condition the museum raise another $50k. On July 15, 1931, the building had its grand opening.4

Fleming Museum groundbreaking, July 1, 1931. Dean George Perkins is the bearded gentleman, and his son, Henry, is the man at right behind him with a raised leg. University of Vermont Archives. Accessed from University of Vermont Landscape Change Program In contrast to the earlier natural history museum, the Fleming prioritized display of the archaeological and fine arts donations of patrons. The museum had galleries dedicated to art, geology, and anthropology—a gallery that featured non-western art and natural history. Japanese art was housed, however, in a separate room and included gifts from the Emperor of Japan to the museum’s donors. Additional natural history collections were displayed on the second floor. The museum also hosted the Wilbur Room, a reading room and repository of historical Vermont documents and artifacts, donated James B. Wilbur. The most popular room of the museum’s early days proved to be the Children’s Room which hosted school groups, story hours, and an immensely popular series of Saturday lectures.5 In the 1935-1936 report to the director of the Fleming Museum, staff estimated 60,000 visitors per year. 500-700 visitors per day was common, and one Saturday in 1935 saw over a thousand guests.6 Even in its early days the Fleming Museum was a very active and innovative institution. Their investment in the education of children rode a wave of early children’s museums; including the 1899 Brooklyn Children’s Museum and the 1925 Indianapolis Children’s Museum, two notable pioneers.7 In 1938 the museum began hosting a children’s story program on WCAX radio. In 1939, the Fleming took another chance on what proved a popular exhibit series for Vermont’s small blind population; featuring object handling and models of collection items.8 The museum was also available for temporary exhibits prepared by volunteers from the University and community. In what could perhaps be considered a predecessor to the University of Vermont’s Historic Preservation Program, museum affiliates enlisted the help of students in taking photographs and measured drawings for the Old Vermont Buildings Project.9

North elevation of the Fleming Museum, October 4, 2021. Photographer, Noah Sandweiss In 1940, the project culminated in the book Old Vermont Houses, and the incorporation of the photos into the Wilbur Library.10 While the Fleming Museum had shifted the university museum’s focus on natural history toward art, the Fleming began to define itself as an art museum in the 1950s and reoriented its galleries by culture and chronology rather than by academic subject.11 As early as the 1930s, Director Henry Perkins, son of former curator George Perkins, redistributed much of his father’s natural history collection among other departments and storage facilities at the university, turning the museum’s focus toward art and anthropology.12 In a 1957 newspaper article on the transition, director Elizabeth Kirkness explained that art exhibits tended to be more visually appealing and attract larger audiences.13 The museum received accreditation from the American Alliance of Museums in 1978,14 and four years later began a $1.3 million restoration project aimed primarily a modernizing collection storage and adding a rear addition.15

Fleming Museum, view looking north showing 1982 postmodern style addition. Photo by Thomas Visser, 2005 In the Fleming’s first decade museum director Henry Perkins, and to an extent the museum itself, were wrapped up in the controversial Eugenics Survey of Vermont. Eugenical research and education had begun at the University of Vermont under George Perkins in 1886, and intensified under Henry Perkins, director of the Survey from 1931 to his resignation in 1934. Although Perkins publicly advocated for “positive eugenics” through social welfare and education, his organization was instrumental in advocating Vermont’s 1931 sterilization law.16 During a founding meeting of the Eugenics Survey, he suggested investigating whether certain races—namely French-Canadian immigrants—were “breeding more defectives.”17 In a 1929 address to the Executive Council of the Vermont Commission on Country Life, Perkins questioned whether there was a legal way of retaining recidivist criminals with low IQs in reformatories past the expiration of their sentences.18 Drafting a proposal for educational materials on the eugenics in 1931, he suggested that “the intermingling of races and its consequence” was the foremost concern of international relations, and that the characteristics of mixed-race offspring were “most not often the most desirable.” In 1931, Perkins was elected president of the American Eugenics Society.19 As eugenics came under attack for its association with Nazi Germany, the research of Henry Perkins, his assistant Asa Gifford, and student researchers working in the Fleming Museum turned toward the influence of social conditions over race and heredity. In 1936 Perkins was forced to close the Survey for reasons of financial difficulty and increasing controversy, leaving the organization’s materials to the Fleming Museum.20 In the Survey’s 1938 swan-song project, a survey of civic participations by Burlington’s white ethnic groups, the researchers argued on behalf of equality between the groups surveyed and the strong influence of wealth, education, and prejudice. Burlington, according to the researchers, could serve as a representative for cities and towns across America.21 In a 1939 editorial, Perkins decried the detrimental effect of slum conditions on childhood development. “In my office in the Fleming Museum is a pin map of Burlington prepared by two of my students in Eugenics,” Perkins wrote, referring to a survey of Burlington children sent to a reform school, “where the pins are thickest, living conditions are the worst… I am an ardent disciple of the doctrine of heredity, but I cannot shut my eyes to environment.”22 In 1938 Perkins handed over the results of his unpublished eugenics survey conducted between 1925 and 1936 to the Federal Historic Records Survey. In a statement on the findings, he iterated race was not a factor in mental ability.23 In 1939, still under the direction of Perkins, Fleming Museum featured an exhibit by dissident German expressionist Karl Hofer, and allegedly played host to Vermont’s first anti-fascist rally in 1939.24 Notes1. Mrs. Eric J. Wedell, ms., Letter to Mr. Arthur L. Harrington from Mrs. Eric J. Wedell, Assistant to the Director of the Fleming Museum, May 15, 1968. 2. Julie Becker, “Fleming at 50.” Vermont, The University of Vermont, Spring 1982, 13. 3. Wedell. 4. Becker. 5. The Fleming Museum. Booklet published by the Fleming Museum, University of Vermont, 1930s. 6. Report of the Director of the Robert Hull Fleming Museum to the President and Trustees of the University of Vermont, 1935-1936. 1936. 7. Cindy Schofield-Bodt, “A History of Children’s Museums in the United States.” Children’s Environments Quarterly 4, no. 1 (1987): 4–6. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41514609. 8. Report of the Director of the Robert Hull Fleming Museum to the President and Trustees of the University of Vermont, 1938-1939, 1939. 9. Becker. 10. Robert V. Daniels, The University of Vermont, the First Two Hundred Years (University Press of New England, 1991). 11. Wedell. 12. Ibid. 13. Elizabeth Kirkness, “Art Appreciation Growing, Says Fleming Museum Head.” Burlington Free Press, September 10, 1957. 14. “Fleming Museum Accreditation,” UVM Trustee Minutes, University of Vermont Board of Trustees. Vol. 17. April 15, 1978, 1050. 15. Becker. 16. Daniels. 17. Henry F. Perkins, Proposal to the Advisory Committee of the Eugenics Survey of Vermont, September 9, 1925. http://www.uvm.edu/~eugenics/primarydocs/omhpgep090025.xml 18. Henry Perkins, Report of “Human Factor Committee "Minutes of Meeting of the Executive Council of the Vermont Commission on Country Life,” October 9, 1929. 19. Nancy L. Gallagher, “Henry Farnham Perkins and the Eugenics Survey of Vermont,” 1996. 20. H. F. Perkins, letter to Eugenics Survey Advisory Committee, October 20, 1936. http://www.uvm.edu/~eugenics/primarydocs/olhfpac102036.xml 21. Gallagher. 22. Henry Perkins, “Housing and the Next Generation.” Burlington Free Press, February 20, 1939. 23. “Study Neglected Material on Eugenics Survey; To Give Results to the Public.” Burlington Free Press, August 19, 1938. 24. Daniels. |

|

|

Nolin House (1931)By Brooke TalbottThe Nolin House, situated at 589 Main Street, was not always known as the Nolin House, nor did it always belong to the University of Vermont. Originally built as a home for Mr. and Mrs. A.S. Killary, the structure at 589 Main Street was completed in September of 1931.1 The contractor for the project was Harry Hopkins of Essex Junction. In the October 10, 1931 edition of The Burlington Free Press, the Nolin House made headlines; the paper referred to the structure as a “new English type residence” adorning University Hill.2 The original house was composed of eight rooms, with oak floors throughout. The exterior was finished with clapboard and asbestos. The original exterior is mimicked today, as the building is still made of white clapboard. A garage and driveway, no longer standing, were also built. In 1940, the Burlington City Directory lists 589 Main Street as housing Alfred S. Killary, a clerk at ACW Inc, and Sunrise Villa, a tourist home.3 On April 1, 1958, Killary passed away at seventy nine years of age, preceded by his wife, Josie M. Killary, who passed away in 1940.4 As a result, the 1960 Burlington City Directory lists Laura B. Killary, Alfred S. Killary’s daughter, as both the main resident of 589 Main Street and the proprietor of Sunrise Villa.5

Map of section of UVM Campus showing Nolin House, shaded in top left corner. Map made by Brooke Talbott By 1970, the resident of 589 Main Street changed to Mrs. Madeleine B. Nolin, widow of Bernard F. Nolin.6 Mrs. Nolin was a nurse at Birchwood Nursing Home, a facility which still operates in Burlington today. The structure remained a private residence until 1976, when the University of Vermont purchased it from Mrs. Madeleine Nolin with plans to use it for offices for the Office of Residential Life.7 By 1980, the building was being used as the UVM Instructional Development Center.8 Later it provided offices for the UVM Canadian Studies program. Now known as Nolin House, the building currently houses offices for staff of the UVM College of Arts and Sciences.9

589 Main Street, October 2, 2021 view looking southwest. Photo by Brooke Talbott The exterior remains the same as in 1931, but the original garage and driveway have been demolished and the footprint of the original driveway has been replaced by a pedestrian pathway. Notes1. “New English Type Residence on Upper Main Street Just Completed.” The Burlington Free Press (10 October 1931): 12. 2. Ibid. 3. Manning’s Burlington, Winooski and Essex Junction Directory (H.A. Manning Company, 1940). 4. “Alfred Killary, Salesman, Church Leader, Dies,” The Burlington Free Press (2 April 1958): 9. 5. Manning’s Burlington, Winooski, South Burlington and Essex Junction Directory (H.A. Manning Company, 1960). 6. Manning’s Burlington, Winooski, South Burlington and Essex Junction Directory (H.A. Manning Company, 1970). 7. “UVM Buys House,” The Burlington Free Press (18 February 1976): 11. 8. Manning’s Burlington, Winooski, South Burlington and Essex Junction Directory (H.A. Manning Co., Publishers, 1980). 9. UVM Campus Map, The University of Vermont, https://www.uvm.edu/map. |

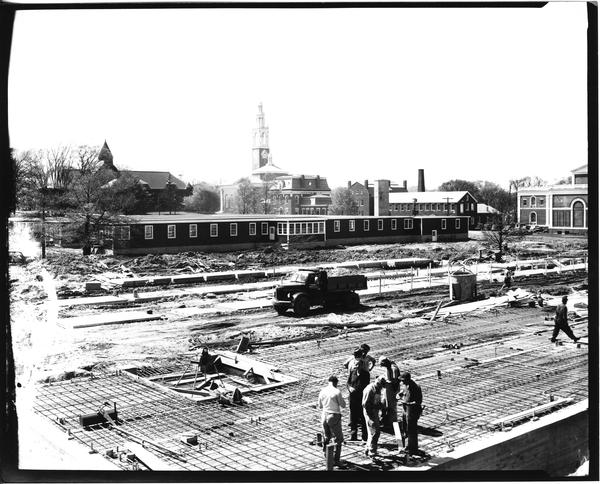

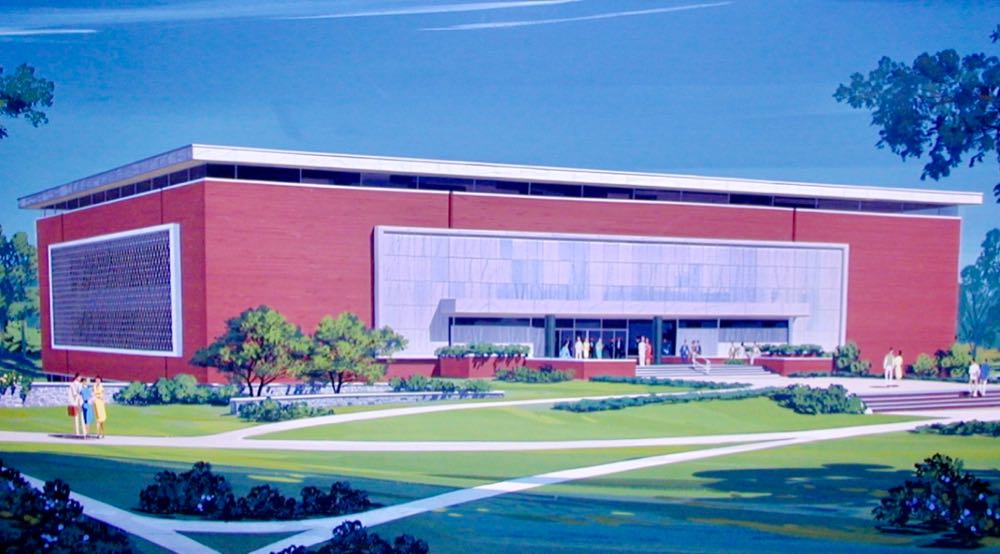

Carrigan Dairy Science Center (1949, demolished 2006)It can be said that Vermont and dairy farming go way back, with the University of Vermont playing a long-standing role in support of the Vermont dairy farmer. In 1911, UVM’s president noted that “Vermont’s dairying industry is in need at this time of special study, and her dairymen of wise counsel.” 1 The College of Agriculture was created that year and housed in Morrill Hall - with administration staff sharing space with “Extension Service, Department of Home Economics, creamery, and seed-, feed-, and fertilizer testing laboratory.” 2 As agricultural science continued to advance in the ensuing decades, the need for more modern facilities for dairy science grew. Comments from Prof. H.B. Ellenberger at a February 1921 public hearing regarding appropriations for a new dairy building at the College illustrate the urgency: the department “is a one-man affair;” “Dairying is taught in the basement.” “The equipment is incomplete; the funds inadequate.” New facilities would not come quickly. In 1942, Joseph Carrigan, previously the Director of Vermont Extension Service, was named Dean of the College of Agriculture. Upon taking his new position, Dean Carrigan found “appall[ing] at the inadequacy of the buildings and equipment of the college,” and made it his focus to mount “a major campaign to get state support for new buildings.”3 Carrigan succeeded, securing funding for three new agricultural science buildings, but it took six years for that effort to come to full fruition.

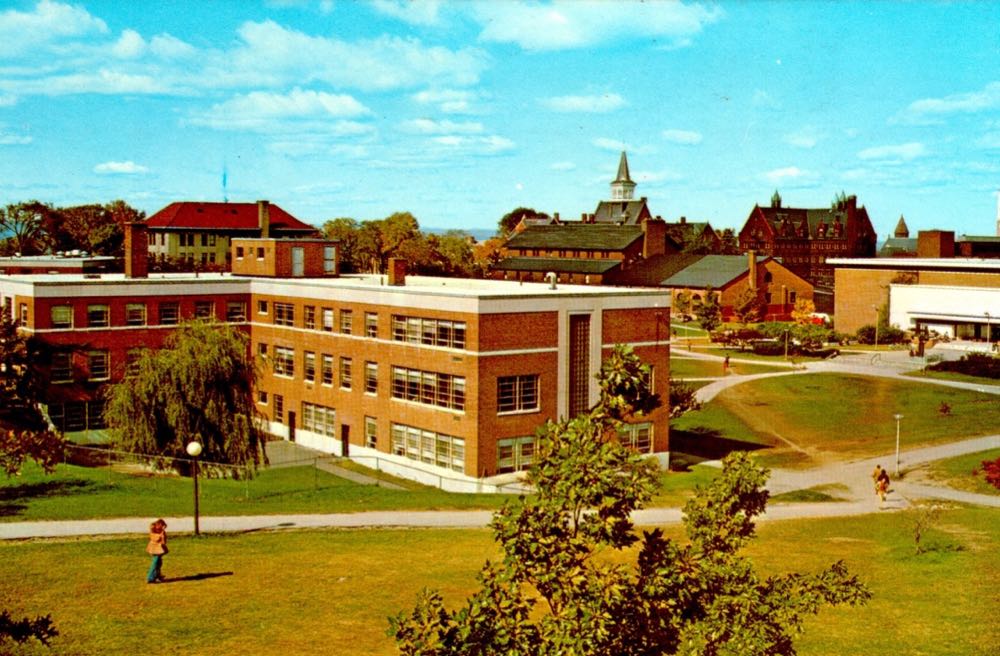

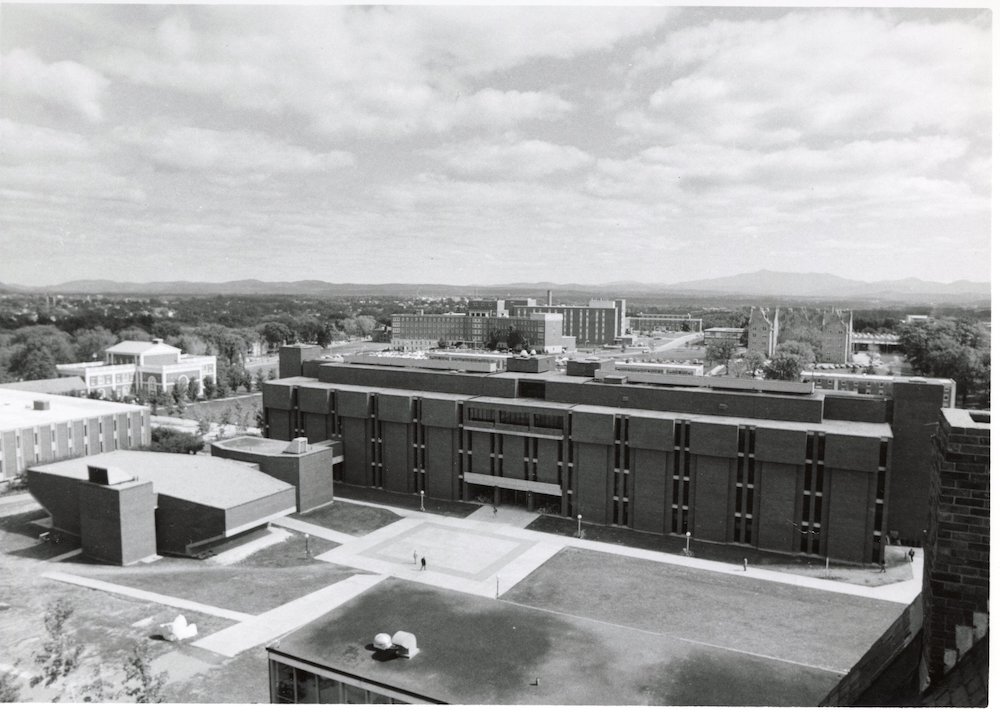

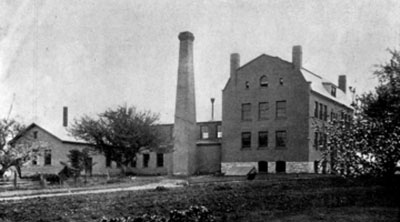

Carrigan Dairy Science Center, circa 1950s. UVM Special Collections The Dairy Science Building opened its doors in 1949, along with the Hills Agricultural Science Building with associated greenhouses, and the Bertha M. Terrill Home Economics Building in 1950. At the building’s dedication in October of 1949, the mood was elated, with the building hailed as a “first class teaching, research, and processing center.” The building contained: "12 offices, a large dairy room, chemical lab, research lab and reading room on the top floor. On the main floor are the milk processing room, cheese room, ice cream room, refrigerator room, and dairy bar."4 There was also a plate glass window viewing area which allowed visitors to watch the manufacturing of ice cream and cheese, and pasteurization and bottling of milk. Dean Carrigan, on leave in Ireland, sent a cablegram to the celebration with his well wishes.6 The building was designed by Alfred T. Granger Associates, according to a photo documentation report by Liz Pritchett Associates (required as mitigation measure for the building’s destruction in 2007). The report notes that Carrigan, along with the Terrill and Hills buildings, was built in the Moderne/Art Deco style.7 Carrigan’s name was attached to the building in his honor in May of 1965.8

Aerial view looking northwest with Main Street at left next to Morrill Hall and Carrigan Dairy Science Center. Terrill Hall is at lower left and Old Mill is at the upper right. Greenhouses are between Carrigan Dairy Science Center and the Old Gym (now Royall Tyler Theater. UVM Special Collections

Carrigan Dairy Science Building west entrance, July 2005. Photo by Thomas Visser The Pritchett Associates report goes into great detail regarding the building’s design, citing its as “one of the best of the few existing examples of Moderne architecture in Vermont.” Distinctive architectural features included “glass block, multi-story continuous vertical windows at each stairwell, intact cast stone that defines the cornice and belt-course, window trim, the wide pilasters that flank the glass block windows, and fluted keystone over the main entrance on the north elevation.” Interior details included “terrazzo flooring in stairhalls, steel stairs, and natural finish birch doors and built-in cabinetry.”9 The building’s significance to the UVM campus relates both to serving the changing needs of the dairy and food processing industry, and to the beloved Dairy Bar housed within. Industry changes continued to impact dairying in Vermont through the years. Pritchett notes that at the time of their construction “the three new buildings were state of the art research facilities that allowed the agricultural college to better pursue its purpose as a fully effective and integral part of the agricultural industry and life of the state.”10 Along the way, adaptations were made to keep pace with the times. According to one study of the industry, when the Dairy building was built in 1949, “most dairy farms were small and diverse. By the 1960s, massive “agribusiness” had been born.”11 By 1997, Carrigan Dairy underwent a major renovation in order to house the new Center for Food Science, with one professor noting that the updated building would bring research like his “into the 21st century.” 12

Carrigan Dairy Science Center, circa 1999. Photo by Thomas Visser Along with its educational mission, the Carrigan Dairy Science Building also had a social role with its Dairy Bar. A student-run institution at its inception, the Dairy Bar was established to train students in dairy foods operations.13 Professor Emeritus Henry Atherton recalls the beginnings as “a small opening, nothing fancy,” with seven or eight flavors of ice cream. But the Dairy Bar grew to become a university institution, as did its ice cream.14 “Best Ice Cream I’ve Ever Had” ran one Burlington Free Press headline in 1976.15 The Dairy Bar even held its own when Ben & Jerry’s came on the scene. By 1991, however, economic constraints forced the University to turn the operation over to private management.16 A decade and a half later in 2006, the building itself was demolished to make way for the new Dudley H. Davis Student Center.17

Carrigan Dairy Science Center demolition, February 2006. Photo by Thomas Visser And yet part of the Carrigan Dairy Science building lives on: the concrete and bricks salvaged from the demolition were used for the sub-base for the new Davis Center.18 Perhaps more importantly, the Dairy Bar’s iconic vinyl stools were salvaged, and are now available for seating in the second floor dining area of Davis.19

The site of the former Carrigan Dairy Science Building in 2021 with Morrill Hall at left and Davis Student Center at right. Photo by Robin Fordham Notes1. Guy Benton, “The Inaugural Address of President Benton,” The Vermonter: The State Magazine, November 1911, 383. 2. Robert Vincent Daniels, The University of Vermont, the First Two Hundred Years (Hanover, NH: University Press of New England, 1991), 193-194. 3. Daniels, The University of Vermont, 193-194. 4. “UVM Has Opened New Dairy Building, Dr. Ellenberger's Dream Comes True,” Burlington Free Press, November 30, 1949, 7. 5. Ibid. 6. “Dairy Building Is Dedicated,” The Alumni, December 1949. 7. Liz Pritchett, “Photographic Documentation of University Farm Building (622 Main Street), Carrigan Dairy Science Building, and Terrill Home Economics Building” (Burlington , VT: Liz Pritchett Associates, n.d.), 1-6. 8. Memo to College and Agriculture and Home Economics Staff, from R.P. Davidson (Director, Extension Service, University of Vermont) re: dedication of Carrigan Dairy Science Building, Box 2, Folder “Carrigan Dairy Science,” UVM Building Info files, University of Vermont Special Collections, Burlington, VT. 9. Pritchett, “Photographic Documentation” 10. Ibid. 11. Ibid. Adrian Everett Logan, “Dairying in Vermont: Farming and the Changing Face of Agriculture, 1945-1992” (thesis, 1998), University of Vermont Special Collections, Burlington, VT. 12. Susan J. Harlow, “Carrigan Renovation to Benefit Businesses,” The University of Vermont Record, January 31, 1997, 1. 13. Eloise Hedbor, “Dairy Bar to Open with New Owners,” Burlington Free Press, January 3, 1991, 1B. 14. Thomas Weaver, “You've Sat There, You'll Sit Here,” Vermont Quarterly, Spring 2006, 64. 15. Debra Weiner, “'Best Ice Cream I Ever Had',” Burlington Free Press, April 17, 1976, 6. 16. Hedbor, “Dairy Bar,” 1B. |

|

|

Chittenden Hall, Buckham Hall, Wills Hall (1949)By Emily Baker The resident dorms known as Chittenden, Buckham-Wills were designed by McKim, Mead, and White architecture firm. The three buildings were modest four-story rectangular buildings and used the new technology of precast concrete panels.1 In 1947, the University of Vermont commissioned three residential dormitories built on what was then known as the “hill” near the former East Hal due to the influx of students that had enrolled into the university after World War Two.2 The construction of what were then known as the Chittenden-Buckham-Wills dorms (more commonly known to the students as either “The Shoeboxes” or “ CBW”), resulted from increased enrollment due to the GI Bill being passed in 1944 by the US Congress.3 These three dormitories were built in 1949 to replace East Hall and a temporary” housing camp that had been set up to accommodate the growing population of freshmen enrolling at the University of Vermont.4

Construction of Chittenden, Buckham and Wills residence halls, circa 1949. View looking northwest with temporary housing beyond that was soon demolished. UVM Archives Each would house around 143 male students per year until it transitioned to a co-ed dorm in the early seventies. These became the first on campus to allow women to visit and see what it was like in the all-male dorm. In a 1955 Vermont Alumni newspaper, the paper announced that “Freshman dorms have an open house,” stating that on Sunday, October 30, first-year female students would be allowed to accompany a male chaperon to see “how the better half lives ” and to explore the dorms.5 In 1982 the dorms were updated and the exteriors were stripped of many original features.

Chittenden Hall, Buckham Hall, Wills Hall, 2015. Photo by Thomas Visser The "CBW shoeboxes" would be home to many UVM students and would play an important role in helping shape students’ lives on campus.

Demolition of Chittenden Hall, Buckham Hall and Wills Hall, July 10, 2015. Photo by Thomas Visser By the summer of 2015, the University of Vermont demolished the old dorms to make way to what is now known as the Central Resident Hall, which was designed by WTW Architects and Scott + Partners Architecture.6 The 2015 demolition left many University of Vermont alumni saddened to see their beloved former dorms destroyed. To preserve the memories and legacy of the dorms, the University of Vermont offered to sell bricks salvaged from the buildings to alumni.7

Central Campus Residence Hall, view looking north. Photo by Thomas Visser, 2017 Notes1. Liz Pritchett, “Historical Building: Evaluations report, first-year student housing and dining project”, 2015. 2. The Key-UVM Development,” Vermont Cynic, September 3, 1949. 3. “About GI Bill Benefits,” Veterans Affairs, December 30, 2020. https://www.va.gov/education/about-gi-bill-benefits/. 4. Pritchett, 2015. 5. "Freshman Dorms Have Open House." Bulletin of the University of Vermont, 1955. 6. Pritchett, 2015. 7. Farewell to the Shoeboxes”, UVM Today, last modified March 9th 2015, https://www.uvm.edu/news/story/farewell-shoeboxes |

|

Joseph L. Hills Agricultural Science Building (1950)By Julia Brown UVM’s Hills Agricultural Science building, built in 1950, was named for Joseph L. Hills, who was Dean of the University of Vermont’s Agricultural Science program as well as the director of the Vermont Agricultural Experiment Station, which was organized by the university, at around the turn of the century.1

Joseph L. Hills Agricultural Science Building, circa 1950s view looking northwest. UVM Special Collections The Agricultural Experiment Station was integral to Vermont’s agricultural landscape, as the station conducted active research on the best and most efficient methods for growing crops, harvesting maple products, caring for livestock, and producing dairy goods.1 The station produced regular bulletins and reports sharing its findings and circulated these bulletins free of charge to anyone who inquired. This allowed local Vermont farmers to have access to the latest findings regarding their own field of work and to ensure that their farming methods were up-to-date and efficient. Along with the bulletins produced by Agricultural Experiment Station under Hills’ direction, a few of his personal speeches survive which hint at his demeanor and scientific outlook. During a talk given at the Connecticut Dairymen’s Association Meeting in January 1901, he asked, “Why should we expect a cow or herd of cows always to give, week after week, the same quality of milk? Milk making is the cow’s work, just as agricultural investigation and teaching and executive duties are my work, and the sundry farming operations, your work. Do we always work as well one day as another whether we feel well or ill? Though in the best of health do we do the same amount of work each day? Why should we expect a cow to do the same day after day? Her work is expressed by the milk she makes, and largely, by the per cent of fat she puts into that milk. We should not expect of her what we ourselves cannot do.”2 Ultimately, the Hills Agricultural Science Building serves as a reminder of UVM’s deep, longstanding roots as a research institution, as it continues to house agricultural studies to this day. Joseph L. Hills Agricultural Science Building, 2021. Photo by Julia Brown Attached to the Hills building is the Joseph E. Carrigan Wing, constructed in 2006. The Carrigan Wing was constructed after the Carrigan Dairy Science building, built 1949, was demolished in 2006 to make room for the Davis Student Center. Both the past and present buildings are so named for Joseph E. Carrigan, who, like Joseph L. Hills, was an active researcher at the Vermont Agricultural Experiment Station. Carrigan graduated from UVM with a Bachelor of Science in agriculture in 1914, continuing on to earn a master’s degree in education in 1931, after which he became the director of the Vermont Agricultural Experiment Station as well as the Dean of the College of Agriculture, the same two positions held by Joseph L. Hills just a few decades before.3 One notable document from Carrigan’s career was a memorandum sent to Vermont Governor W.H. Wills, dated December 23, 1941. Sent just a few weeks after the attacks at Pearl Harbor, Carrigan expresses the responsibility of his agricultural programs in aiding the war effort. “The main job for agriculture during the present emergency due to war is to produce food supplies for our nation and our allies…In this food production program it is obviously essential for Vermont agriculture to gear in with the agriculture of the remainder of the country and also to gear in with the civilian defense program of the state.”4 Carrigan pointed out that he is both on the State USDA Defense Board and the Vermont Council of Safety, and he assured the governor that he took these responsibilities very seriously. “This very fact tends to make for correlation between the United States Department of Agriculture and the Vermont Council of Safety in carrying on agricultural resources and production in the state.”5

Joseph E. Carrigan Wing, 2021. Photo by Julia Brown The Joseph E. Carrigan Wing now houses UVM’s Department of Nutrition and Food Sciences. Though the Carrigan Wing and the Hills Agricultural Science building were constructed in vastly different time periods and in vastly different architectural styles, the two building’s physical connection tells the story of two influential scientists with identical roles and interests. Notes1. The University of Vermont Historic Preservation Program. University of Vermont Campus Treasures. Accessed September 21, 2021. http://www.uvm.edu/~campus/index.html. 2. Abstract Twentieth Report, 1906-1907. Report no. 137. Vermont Agricultural Experiment Station, The University of Vermont. Burlington, VT: Free Press Printing, 1908. 3. Joseph L. Hills, "What Makes the Milk and Cream Tests Vary So?" Address, Connecticut Dairymen's Association, January 16, 1901, Hartford, Connecticut, November 8, 2021. 4. "Joseph E. Carrigan Dies, Was UVM Agriculturalist." Rutland Daily Herald, May 25, 1984. Accessed September 21, 2021. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/41092717/obituary-for-joseph-e-carrigan-aged/. 5. "Memorandum." Joseph E. Carrigan, Agricultural Resources and Production, Vermont Council of Safety, to Governor W. H. Wills. December 23, 1941. |

|

Bertha Terrill Home Economics Building (1950)By Emily Baker Terrill Hall was constructed in 1950 for UVM Home Economics Studies through the 1950s to the 1970s. This building is now home to the Department of Animal Science and the Nutrition and Food Science Department .Before Terrill Hall was built, a “home management house” on Summit Street was used as a hybrid living and teaching space, and in some regards, it was the precursor to the living and learning complexes that are now common on campus. The house would act as a place for female students in their senior year to practice what they had learned throughout their time at the University of Vermont. The students would pay five dollars for room and board at the house. Towards the rear of the building, there was an annex used as an instructional laboratory where the students would also take care of pre-school age children.1

Terrill Hall, circa 1951. Courtesy UVM Special Collections