1920s

BURLINGTON LANDMARKS

Ira Allen Chapel

By Austin White

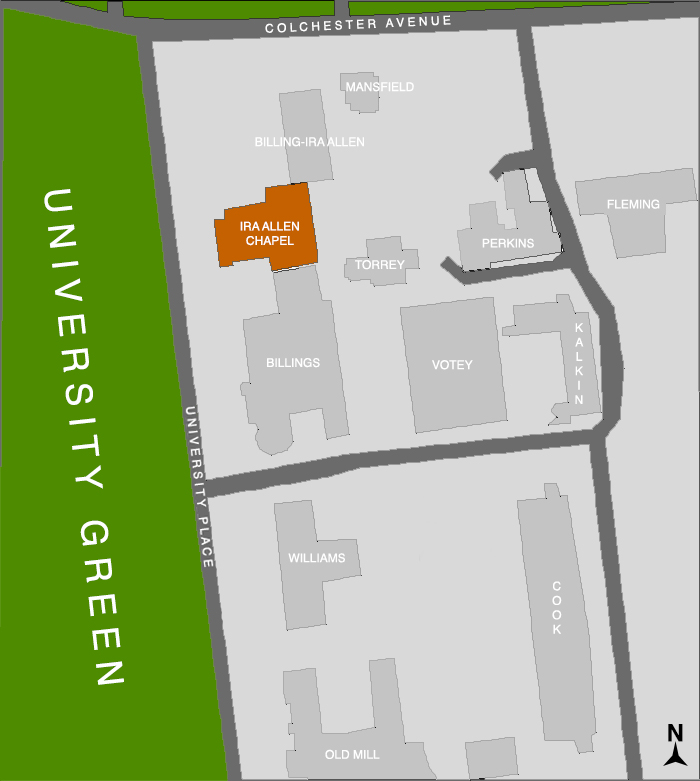

Conceived in 1924 with completion and dedication three years later, the University of Vermont’s Ira Allen Chapel is an architectural icon sited facing the University Green on the corner of University Place and Colchester Avenue. It has hosted commencements, lectures, and cultural performances for the student body and the Burlington community and beyond for nearly ninety years.

Wherever viewed at ground level, the chapel exhibits a colossal presence. Viewed from afar, its prominent tower serves as a beacon, illuminating a path toward academic and intellectual achievement and enlightenment. Its concept and funding was provided by James P. Wilbur, a philanthropist from Manchester, Vermont, who laid the cornerstone. A magnificent dedication ceremony for the Ira Allen Chapel was held on January 14th, 1927.

This paper will explore the background and origins of Ira Allen Chapel, beginning with the religious, social, and academic components that inspired and necessitated its construction. Additionally, the stories of those who arranged, financed, designed, and built the chapel will be woven in throughout for context. What contributing factors, if any, significantly impacted the chapel’s timeline? Who benefited the most from its erection? And were results satisfactory to those most intimately involved?

Origins of UVM campus chapel services

Founded in 1791 as private institution (eventually gaining quasi-public status),1 the University of Vermont was an outlier amongst its contemporaries (although the first nine consecutive presidents, beginning with Reverend Daniel Clark Sanders, were Congregationalist ministers).2 However, religion was commonplace in a society grappling with its transition into secularity, playing a vital role in the life of nearly every American. Despite a First Amendment clause from the recently ratified Constitution, which explicitly stated the separation of church and state, it would be a couple decades until other states followed suit. For example, it was not until 1818 when Congregationalism was no longer the established faith of Connecticut.3

Despite an ostensibly secular foundation, the university’s environment and curriculum fostered and projected a spiritual image. Chapel exercises were held in the “College Edifice,” built on the site of Old Mill between 1801 and 1806.4 The original main campus building also included classrooms, a dormitory, library, lecture halls, infirmary, communal lounges, and a geological display.” After a destructive fire 1824, “Middle College” was completed five years later with a chapel.

University modernizes and rapidly expands

The Civil War ravaged the United States, and had an immensely disproportionate effect on UVM, resulting in plummeting enrollment through drafts, fatalities, and permanent academic departures. Consequentially, the school was financially strained, the administration sought additional sources of funding. Professor Joseph Torrey, elected the same year as the onset of the war, initiated the first steps toward modernization. During his tenure, the university absorbed the State Agricultural College through the Morrill Act,5 legislation sponsored by Vermont Senator Justin Morrill which created land grant colleges with purpose of bolstering agricultural curriculum.6 Unfortunately, this expansion was an insufficient remedy, and Torrey resigned in 1866.7

His successor, James B. Angell, editor of the Providence Journal, was elected at a difficult and uncertain junction. The passage of the Morrill Act generated tension between academics and area farmers. The former was apprehensive about educational declination, and favoritism toward a scholarly curriculum over banausic skills by the latter.8 In his autobiography, Angell describes the measures undertaken by him to address the university’s instability, “My task was to organize the Agricultural College and effect a harmonious union with the old college, to aid in raising funds which it was clearly seen were needed, and to inspire the public and especially the alumni with the confident belief that the Institution really had a future.” (122-123)9

President Angell’s efforts to rescue the university from its Civil War-wrought financial perils were immensely successful. Although he only served five years, beginning with monetary and academic crises, he doubled enrollment by 1870. Additionally, he oversaw the fundraising of eighty thousand dollars, and increased annual professor salaries by three hundred dollars to a total of $1500. Perhaps his most important academic appointment was that of zoology and botany professor George H. Perkins. He furthered his modernization initiatives with the addition of a new scientific laboratory and renovations of buildings throughout campus. His house was erected on the corner of Colchester Avenue and University Place, which would be razed just over a half century later to build a new chapel.10 There is perhaps an irony to this, as Angell’s efforts eventually were the catalyst an enrollment explosions, which would quickly lead to capacity strains in the current chapel.

Despite the growth of the university after its acquisition of the State Agricultural College and appointment of Professor Perkins, which signaled a nascent shift towards modernizing initiatives that emphasized the sciences, religion was still an integral component of the environment and culture. As the opening speaker of President Matthew Buckham’s inauguration, outgoing President Angell’s address reiterated this notion when he described Buckham as a “prophet,” “his marked power as a preacher,” and most explicitly, “his mainly Christian character.”11

Buckham’s administration oversaw the first female student admission,12 expansive construction of campus buildings, just one short of quadrupling to twenty-five (including the monumental Billings Library), and drastic increases of faculty and student enrollment (over eighty and five hundred, respectively).13 Underneath his progressive agendas and accomplishments still lay his spiritual rigidity, and daily chapel attendance was compulsory and monitored, with services beginning sometime between eight and eight-thirty in the morning. However, towards the end of his tenure, attendance had markedly decreased, much to his consternation; the rapid growth of the student body had pushed the old chapel’s (then located in “Old Mill”) capacity, and was insufficiently warmed for morning service due to its substandard heating system. The culmination of these factors led to the realization that a new chapel was much needed. In the May following President Buckham’s death in 1910, an anonymous letter was written in U.V.M. Notes called for a replacement chapel to be named in his honor to “perpetuate invisible and tangible form the noble Christian spirit and influence which characterized his long life of public service.”14

James Benjamin Wilbur, benefactor of the Ira Allen Chapel

A philanthropic Midwestern transplant who, in 1909, retired to Manchester, Vermont, James B. Wilbur became an ardent supporter of the university through several donations and establishments. Born on November 11th, 1856, Wilbur amassed his fortune between 1876 and 1909 while working for and managing a few entities; a cashier for the New York, New Haven & Hartford Railroad Company, banking and ranching in Colorado, then finally the Royal Trust Company of Chicago, which was founded and administered under his direction. Outside UVM, Wilbur had endowed $100,000 to the Library of Congress Trust Fund Board, of whom he was a trustee.15 His attempted donation of $100,000 to the Hundred Neediest Cases Fund, established by the New York Times, which aided in provision of basic quality of life necessities, was declined on the basis that its disproportionate amount would defeat the charity’s purpose of having several, smaller donations.16 As evidenced from his many donations and publications, Wilbur had a deep appreciation for history. He was a trustee of the American Antiquarian and New York Historical Societies, and a member of the Massachusetts Historical Society.17 His interest, passion, and dedication became even more apparent and fulfilled after his retirement to Manchester. His first philanthropic venture was his involvement in municipal works, at both the state and local levels, notably his promotion of the Manchester Village and Center Improvements Association, with the objective of improving transportation infrastructure and educational facilities.18 Wilbur also began a farming venture at his Willburton Hall estate (previously named Strawberry Hill, purchased from fellow Chicagoan A.M. Gilbert).19 Willburton Hall operated as dairy and sheep farm, which included the breeding and raising of Ayrshire cattle and Hampshiredown sheep.20 Wilbur’s community improvement initiatives evoked his ardent historical interests. His extensive compilation of the state’s early records, manuscripts, and other materials became a repository of Vermont’s history. Throughout his collection and research, Wilbur began focusing on Ira Allen, the oft-slighted and unassuming younger brother of Ethan. Despite the lack of adventurous exploits as like heroically-celebrated elder sibling, Ira was instrumental in many political affairs in Vermont and surrounding states.21 One of his most celebrated achievements was his establishment of the University of Vermont in 1791. However, Ira, like his brother, had a deceitful reputation.

Both had envisaged a massive commercial empire in the Champlain Valley for lucrative trade with Europe. Additionally, the supposed “Haldimand Negotiations,” where the Allens secretly negotiated with the Canadian agent Justus Sherwood to possibly have the United Kingdom annex Vermont, notably to protect it from a likely invasion from New York. Ira’s chief scheme was the Olive Branch Affair, a failed attempt to arm Quebecois to revolt against their British rulers. Under the guise of arming Vermont militiamen, Ira attempted to smuggle arms and cannons from France, however, his ship and its contents were intercepted by the British Navy. He even went as far as to create a new flag that would be raised at overrun Canadian positions.22 Wilbur failed to discover Ira’s unsavory actions during research in Paris for his 1928 two-volume biography Ira Allen, Founder of Vermont, 1751-1814. This was due to his reliance on English-only correspondence, which itself was a mask for Ira’s true intentions.23

Throughout most of the 1920’s, Wilbur was looking for an archive to house his collection, preferably in the Billings Library. Upon his death in 1929, the university was named in his will as the recipient of Vermontania, along with $100,000 for its care, and additional $3,000,000 towards other endeavors,24 half of which for a scholarship fund for UVM students.25 It is now housed in the university’s Special Collections department in the Bailey/Howe Library.26

Wilbur’s first Ira Allen memorial

Ira Allen, Founder of Vermont, 1751-1814, was the last of Wilbur’s three dedications to Allen, the first being a bronze statue. Sculpted by famed New York City artist Sherry Fry,27 his cast bronze work was dedicated on June 18th, 1921. The event, described as “most impressive and “attended by an unusually large gathering,” was witnessed by several dignitaries, such Vermont governor J. Hartness, Burlington mayor J. Holmes Jackson, Fort Ethan Allen commandant Colonel Edgar A. Sirmyer, the University of Vermont Board of Trustees and former Massachusetts governor Eugene N. Foss.28 The ceremony emulated Christian worship, complete with introductory and closing prayers by the university’s chaplain, hymns, and the Burlington High School and Junior High School’s performance of “America the Beautiful.”29 In his presentation, Wilbur called Allen “the guiding hand at every crisis,” and President Bailey pledged that “the spirit of Ira Allen shall be kept alive on this campus and in our University halls, and his deeds will always be cherished among our Vermont traditions.” Perhaps most befittingly, Sarah M. Allen unveiled the immortalized representation of her grandfather.30

Ira Allen Chapel: Vision, announcement, planning, construction, and dedication

After decades of rapid expansion and enrollment, which further burdened the already-deficient capacity of the current chapel, not to mention the woeful heating system, the time had finally come for a new, grand chapel. Any construction was to be an appropriate tribute to a mighty university founded by a noble statesman, one who fought, negotiated, and sacrificed himself for the foundation and benefit of the republic, then state, of Vermont. Once again, James B. Wilbur would bless the university with an endowment, this time to fund a monumental shrine.

Wilbur had conceived of the idea to honor Allen with a chapel in 1923, much to the elation of President Guy W. Bailey. “I appreciate more and more the fact that it would be very valuable to all connected with the University if we had a chapel where our entire student body could meet each morning with a brief exercise,” wrote Bailey to Wilbur.31 By that year’s fall semester, enrollment had swelled to eleven hundred forty-six students, and the plan to build venue in which the entire student body could comfortably assemble began to formulate. The famed New York City firm of McKim, Mead, and White, unanimously voted in the previous year by the Board of Trustees as the university’s official architects,32 would design the chapel. O.S. Nichols of Essex Junction was designated the contractor,33 and the Drury Brick Company, also of Essex Junction, would supply the locally-fired bricks used in the edifice.34

The firm’s initial plans, led by William Kendall, caused Wilbur financial apprehension, noting, “[The Chapel] plans are artistic, but I am afraid too expensive for me.”35 Wilbur urged Bailey to review the sketches, along with Deans Josiah Votey and Walter Crocket, and Professor Frederick Tupper. The quartet of administrators approved of Kendall’s proposals, including the one-hundred seventy foot tower, where “the light would be visible from the entire countryside between Burlington and Mount Mansfield and on the other hand, would visible from the lake town on the New York side.”36 To help alleviate a possible funding shortfall, Bailey also placed an advertisement in the university’s Alumni Weekly in order to generate revenue.37 Aside from his endowment, Wilbur offered an additional $150,000 of timber sold from his property in Vancouver Island, British Columbia.38

Plans for the new chapel were officially announced by Wilbur during his speech to the university’s Board of Trustees on June 21st, 1924. His opening statement venerated Allen,

I know when I am called up to say a few words to you, it is expected that I will speak of the noble man that founded this institution. However in speaking of him I shall not forget that he was a man of very few words. In a crisis of his life, when his liberty was taken from him, he felt it necessary to remarks, that he was not in the habit of telling what he was going to do, but what he had done. We all admire that trait and wish this state and this country had more men that had formed this habit. Most men who have succeeded in their undertakings have possessed or acquired it,

He concluded, “I do this out of respect for the memory of the one whom I consider Vermont’s greatest and most neglected citizens, Ira Allen.”39

By early 1925, plans and contracts for Ira Allen Chapel had been fulfilled. A site for the new chapel was selected, and prominent place on the northeast corner of the University Green, completing an impressively eclectic row of architecture, with each building representing a remarkable period of the university’s past; from the corner of University Place and Main Street northward to the corner of Colchester Avenue; Morrill Hall, Old Mill, Williams Hall, Billings, and Angell Hall. The latter, the former president’s house, built in 1869 for James Angell, then subsequently occupied by Matthew Buckham and Guy Benton, had since 1917 served as a women’s dormitory. It would need to be razed.40

On Saturday, June 20th, 1925, a ceremony was held to commemorate the laying of the chapel’s cornerstone, which was symbolic, for Old Mill’s cornerstone was laid exactly one hundred years prior. The Reverend John Lowe Fort officiated with an opening prayer, followed by the “Glorious Things of Thee Are Spoken.” After the hymn was the “Laying of Cornerstone,” during which Wilbur reaffirmed his praise for Allen, dedicating the chapel to his “character” and “not by any special service.”41 Following Wilbur’s speech, President Bailey delivered an address regarding the cornerstone’s description, which reads, “Dedicated to the service of God, erected in memory of the founder of this University, Ira Allen, 1925.” Other university representatives offered remarks; Board of Trustee Warren Robinson Austin, Professor Samuel Eliot Bassett, and undergraduates Edward Carlton Abbott and Anne Dauchy.

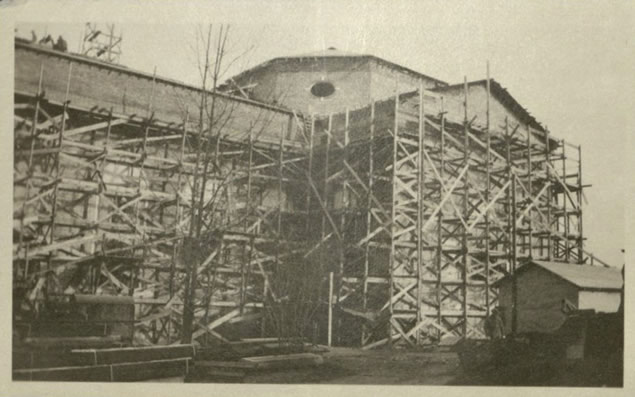

Construction of the chapel had continued at a reasonable pace, however, by July of 1926, rumors began to spread about the structural integrity of the wooden tower. Taking these hazardous and even potentially-fatal conditions with merit, the university hired New York City engineering consultant H.G. Balcom, noted for his consultation of Grand Central Station’s construction, at the suggestion of alumnus Willis E. Weston, who, like Balcom, was a structural engineer. After his assessment, Balcom declared the tower to be sound. Construction resumed shortly afterwards.42

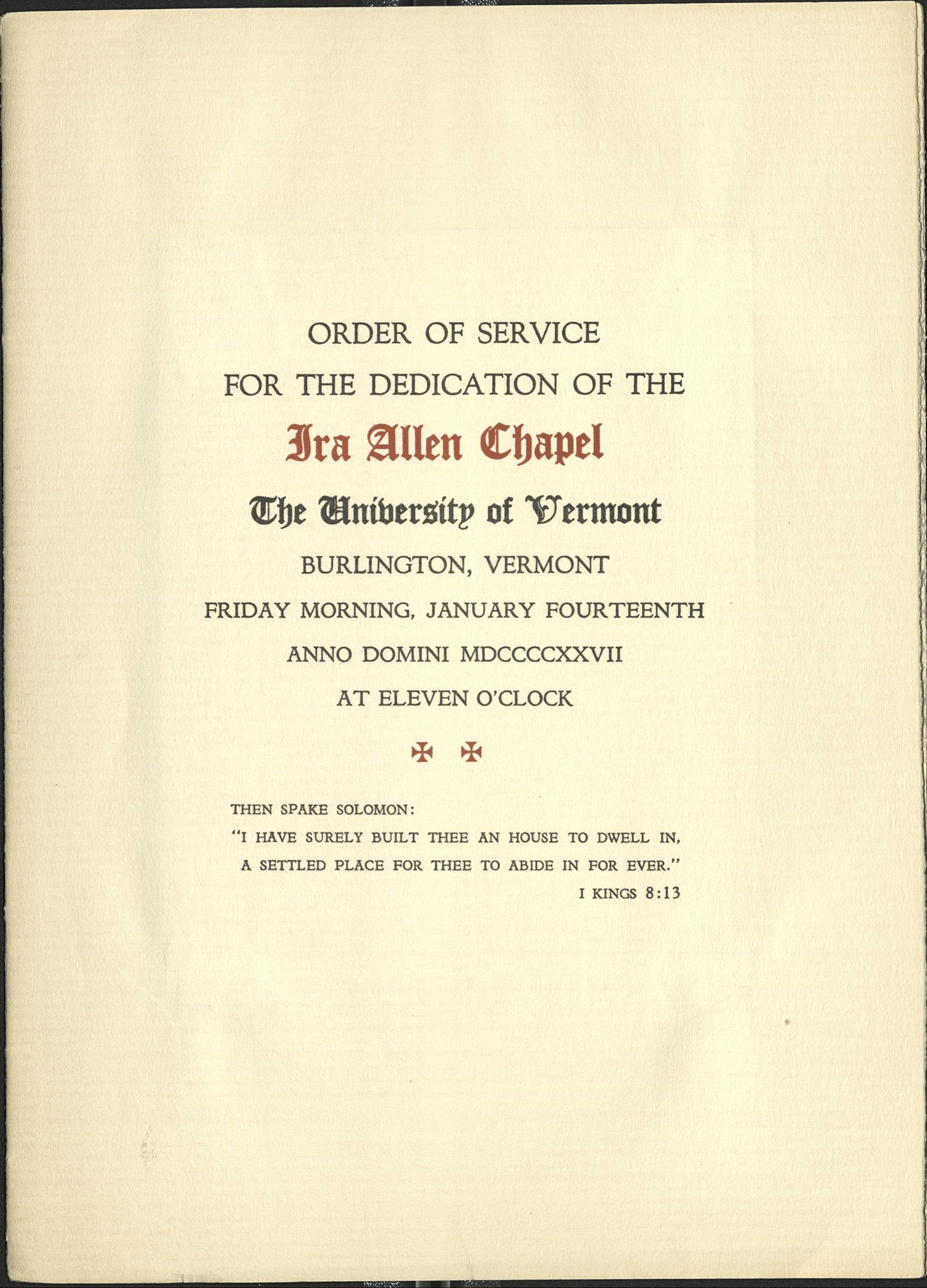

Five months later, the Ira Allen Chapel was complete and preparations for its grand dedication were underway. A three-part service was scheduled for Friday, January 14th, 1927, beginning at eleven o’clock in the morning with an address by New York City’s Broadway Tabernacle pastor Reverend Charles Edward Jefferson. At four o’clock, the first of the two organ performances would be led by the choir master of New York’s St. Thomas Church; the first, a concert, and the second, a recital. A choir comprised of sixty university students was assembled, and would deliver a rendition of Johann Sebastian Bach’s anthemic “Now Let Every Tongue Adore Thee.” Due to the immense size of the ceremony, not only in performance but the roster of university and out-of-state luminaries, and members of the local community, seating was minimal. Admission required tickets, which were already limited. Logistical management by university officials allowed student attendance only to those in the senior class.43

When the clock struck eleven that Friday morning, the formal event had commenced. The dedication sermon, orated by Reverend Jefferson, opened with a verse from Matthew 5:16; “Let your light shine before men, that they may see your good works and glorify your father which is in heaven.”44 His words continued to extol the virtuosity of a model Christian, as well as metaphorical references to shining lights and opened doors, intimating a church service rather than an honorific ceremony of a statesman such as Allen.

As was expected, there was an impressive and esteemed collection, amongst others, of university officials, politicians, and clergy, such as Bishop A.C.A. Hall of Vermont’s Episcopal Church, Norwich University, dean Captain H.R. Roberts, Vermont education commissioner Clarence H. Dempsey, along with President Bailey and the university’s Board of Trustees. Student ushers assisted with seating, which was surely overwhelming due to fulfillment of capacity. Wilbur received the chapel keys from Bailey, after which he declared, “Education without religion does not meet the needs of this day, and that the University of Vermont is not complete without of place of worship.”45 He was most sincere about this belief. One month after the chapel’s dedication, Wilbur expressed to Bailey that his intention for Ira Allen Chapel was strictly for none other than religious purposes, and to facilitate regularly attended services within a building capable of hosting such exercises. Additionally, Wilbur hoped to foster a stronger bond and unity among the student body with these services by referencing to “guidance.”46 The musical accompaniment was equally impressive. A Welte Reproducing Organ and choirs piped and sang classic hymns, including two Hebrew scores, witnessed by souls occupying every seat, including those in the gallery. The university’s Women’s Glee Club performed Rachmaninoff’s “Glorious Forever” and Mendelssohn’s “Life Thine Eyes.”4

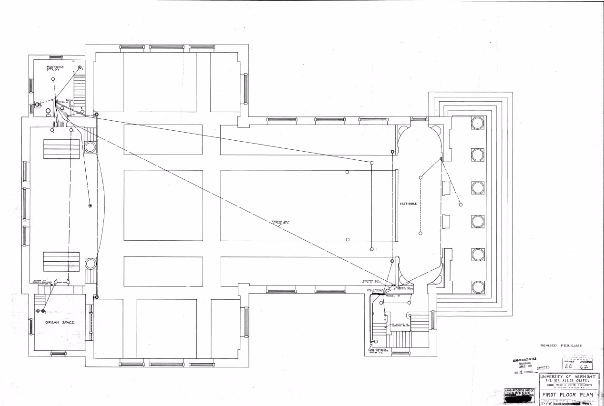

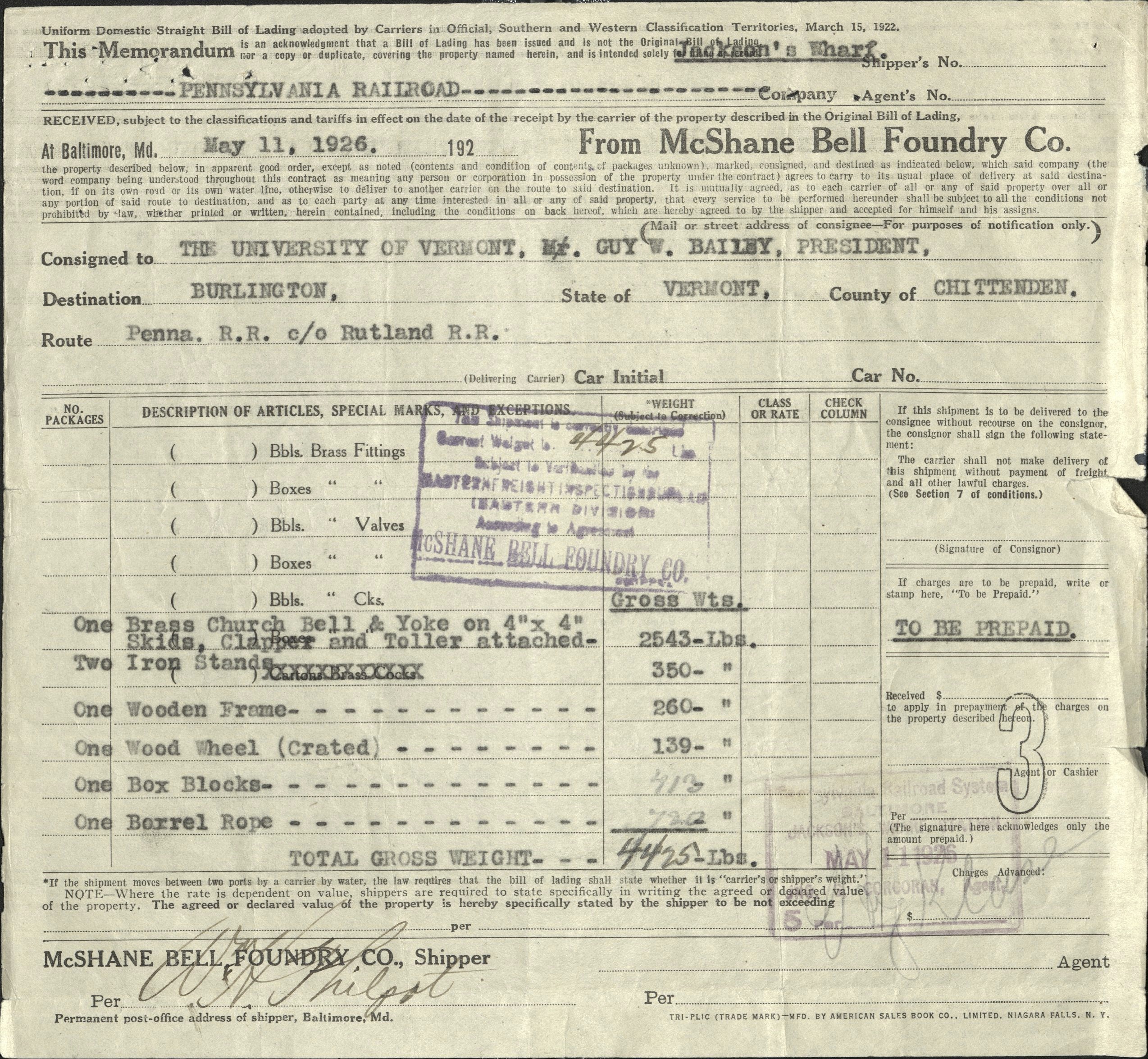

Wilbur’s finished product, one in the making for almost five years, could now serve the university and beyond. Its plan and presentation alludes to the holy character upon which Wilbur regarded Allen. Appropriately, it was fashioned as a New England meeting house, a homage to the to the architecture style of Allen’s life. Its Classical Revival form, a favored by McKim, Mead, and White, believed that “it is not only more in keeping with American precedent, but more flexible, easier to maintain, and better suited to our climate and mode of campus life than style derived from the Gothic or Romanesque.”48 The chapel’s cruciform plan intimated a cathedral, complete with a vestibule, nave, aisles, transepts, a dome, and an east-facing chancel. Ira Allen Chapel would not have a steeple, but a substitute 170-foot campanile, with an eight-foot clock placed on all four facades,49 whose top would encase a 2543 lb. McShane Bell Foundry, Co., bell (shipped from Baltimore),50 housing a 200-watt tungsten beacon light and topped with a lightning rod. Keeping true to their aesthetics preferences, the firm designed the chapel with a blend of Georgian, Federal, and Greek Revival elements; Palladian windows (double hung, with 16 over 16 and 24 over 24 sashes), a pedimented portico supported by Ionic orders, full entablature, Classical ornamentation, slate roofs, a second story gallery, chancel-flanking pilasters, and a brick edifice with contrasting white-painted wood.51

The Ira Allen Chapel is a reflection of the decade in which it was conceived and birthed. The “Roaring Twenties,” a time of exponential growth, witnessed massive immigration resulting from World War One, and introduced many cultures and religions who did not have a historically prominent or established presence in the United States, especially Roman Catholicism, Eastern Orthodoxy, and Judaism. This caused an existential crisis among the historically dominant and majority white Protestant community, which inspired and birthed a swath of xenophobia and nativist movements.

Patriotism was at a fever pitch following the United States’ victory in the War, an event which solidified its position as reputable military, political, and economic force on the global stage. With that came a renewed sense of and appreciation for history and a focus on oft-lauded commanders, generals, and other military figures. Economic prosperity led to building booms nationwide, with monumental structures that pushed the limits of funding to showcase affluence and power. On the other end, however, were many philanthropists, funding a variety of charities, scholarships, libraries, and other academic and civic ventures.

James B. Wilbur’s donation to the University of Vermont, including his persona, is an assembly of the attitudes, movements, and emotions of the 1920’s. A white Protestant millionaire and a generous benefactor, who stressed the importance of Christian faith and worship, almost singlehandedly resurrected Ira Allen, an adopted patriot and son of Vermont, who sacrificed himself for the welfare of others. Wilbur synthesized his devotion to Christ with Ira Allen through his passion for history and higher education with the glorious chapel, one that lets the light shine high for all to see.

NOTES:

1. “University of Vermont v. Town of Essex,” JUSTIA US Law, http://law.justia.com/cases/vermont/supreme-court/1971/177-70-0.html.

2. Jeffrey D. Marshall. Universitas Viridis Montis 1791-1991 An exhibition of documents and artifacts telling the story of The University of Vermont (Burlington, Vermont: The University of Vermont, 1991), 12.

3. Wesley W. Horton, The Connecticut State Constitution / Wesley W. Horton ; [foreword by Ellen Ash Peters]. 2nd ed. Oxford Commentaries on the State Constitutions of the United States. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012), 10.

4. “UVM History 101,” Vermont Quarterly: University of Vermont, http://www.uvm.edu/vq/?Page=news&storyID=23028&category=vq-fetrs.

5. Marshall, 34.

6. Morrill Act of 1862, 7 U.S.C. ch. 13 § 301 et seq. (1862).

7. Marshall, 34.

8. “James B. Angell (1866-1871),” University of Vermont, https://www.uvm.edu/president/formerpresidents/?Page=angell.html, last modified September 28th, 2012.

9. The Reminisces of James Burrill Angell (London, Bombay, and Calcutta: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1912), 122-123.

10. “James B. Angell (1866-1871).”

11. “Inauguration of Prof. M. H. Buckingham as President of the University of Vermont and Agricultural College, August 2nd, 1871,” 3-4.

12. Rachel Moeller Gorman, “The First Women,” Vermont Medicine, Spring (2004): 16.

13. U.V.M. Notes vol. 07 no. 03, Special Collections, University of Vermont Libraries, Special Collections, 5.

14. J.L. Hills Papers, “The History of University of Vermont Buildings: 1800–1947,” University of Vermont Libraries, Special Collections, Burlington, Vermont: Special Collections Department, 1949, 55.

15. “Appeal For Neediest To Start Next Week,” New York Times, December 1, 1929.

16. “Wilbur Will Aids Neediest Cases Fund,” New York Times, June 19, 1929.

17. The Quarterly Journal of the New York State Historical Association, Vol. 10, No. 3 (July, 1929), 225.

18. Mary Hard Bort, Manchester: Memories of a Mountain Valet (Manchester, VT and Tucson, AZ: Manchester Historical Society and Marshal Jones Company, 2005), 263.

19. Ibid, 270-271.

20. “Obituaries,” The Quarterly Journal of the New York State Historical Association, 225-226.

21. The American Historical Review, Vol. 34, No. 2 (Jan., 1929), 373.

22. Charles T. Morressey, “Classic: Ira and Ethan Allen and the Republic of Vermont,” New England Living, last modified February 11, 2008, https://newengland.com/today/living/new-england-history/vermontflag.

23. Ibid.

24. Tom Bassett, “The Development of UVM’s Vermontania Collection,” Liber: A Newsletter for The Friends of Special Collections at UVM (Spring 1987), 2.

25. “Wilbur Society,” The University of Vermont Foundation, http://www.uvmfoundation.org/s/1690/foundation/index.aspx?sid=1690&gid=2&pgid=493.

26. “Robert Hull Fleming Museum,” The University of Vermont, http://www.uvm.edu/~campus/fleming/fleminghistory.html.

27. “Dedication of Statue of Ira Allen – June 18, 1921,” the University of Vermont, pamphlet.

28. “James B. Wilbur Formally Presents Ira Allen Statue,” Burlington Daily Free Press, June 20, 1921.

29. “Dedication of Statue of Ira Allen.”

30. Ibid.

31. Guy W. Bailey to James B. Wilbur, October 3, 1923, in Office of the President (Guy Bailey) Records, vol.1., University of Vermont Libraries, Special Collections, 63.

32. Ibid, 35.

33. Guy W. Bailey to James B. Wilbur, February 15, 1924, in Office of the President (Guy Bailey) Records, vol.1., University of Vermont Libraries, Special Collections, 87.

34. Lillian Barker Carlisle, Look Around Essex and Williston, Vermont (Burlington, Vermont: Chittenden County Historical Society, 1973), 16-17.

35. James B. Wilbur to Guy W. Bailey, November 29, 1923, in Office of the President (Guy Bailey) Records, vol. 1., University of Vermont Libraries, Special Collections, 69.

36. Guy W. Bailey to James B. Wilbur, February 2, 1924, in Office of the President (Guy Bailey) Records, vol. 1., University of Vermont Libraries, Special Collections, 83, 84.

37. Ibid, 84.

38. James B. Wilbur to Guy W. Bailey, June 16, 1924, in Office of the President (Guy Bailey) Records, vol. 1., University of Vermont Libraries, Special Collections, 100; Edwin B. Abbott to University of Vermont, May 27, 1929, in Office of the President (Guy Bailey) Records, vol. 2., University of Vermont Libraries, Special Collections, 260.

39. Ibid.

40. “Facts Concerning the Ira Allen Chapel,” Vermont Alumni Weekly, vol. 4, no. 16, February 12, 1925.

41. “James B. Wilbur, Donor, Lays Cornerstone Of Ira Allen Chapel at University,” Burlington Free Press and Times, June 23, 1925.

42. “No Serious Troubles with Ira Allen Chapel Tower,” Vermont Alumni Weekly, July 14, 1926.

43. “Arrangements Completed For Dedication Of Ira Allen Chapel On January 14, 1927,” Burlington Free Press and Times, January 3, 1927.

44. “Ira Allen Chapel at University of Vermont is Formally Dedicated,” January 14, 1927,” Burlington Free Press and Times, January 15, 1927.

45. Ibid.

46. James B. Wilbur to Guy W. Bailey, February 20, 1927, in Office of the President (Guy Bailey) Records, vol. 2., University of Vermont Libraries, Special Collections, 345.

47. “Ira Allen Chapel at University of Vermont is Formally Dedicated.”

48. McKim, Mead, and White, Recent Buildings Designed for Educational Institutions (Philadelphia, New York, Springfield, Mass: The Beck Engraving Company, 1936), 4.

49. “Order of Service for the Dedication of the Ira Allen Chapel - January 14, 1927,” University of Vermont, pamphlet.

50. “The University of Vermont, Guy W. Bailey, President,” invoice, McShane Bell Foundry, Co., Baltimore, May 11, 1926.

51. “Plan Showing New Location for Chapel Building,” Building plans, courtesy Campus Planning Services, University of Vermont.

52. “Order of Service for the Dedication of the Ira Allen Chapel.”