1920s

BURLINGTON LANDMARKS

City Hall - The Pride of Burlington

By Adrienne Dickerson

Eras are defined by their achievements and failures, and the golden age of the 1920s was no different. Beginning with an emotional and economic high resulting from victory in World War I and ending in absolute antithesis with the stock market crash of 1929 and the ensuing Great Depression, the “Roaring 1920s” were a time of incredible growth and development. Advancements in technology, medicine, political and social equality brought about a transformation in our country. These advancements created a new societal landscape, which afforded the average American the freedom and ability to begin thinking and living on a much larger scale. Advent of the wireless radio and its rapid spread during the 1920s gave the general public access to a world outside of their own, something that had only previously been done through printed text. Henry Ford’s methods of assembly line production allowed for manufacture of a vehicle that was affordable to most which in turn made leisure travel an activity, and destinations such as Burlington, no longer reserved for the wealthy.1 With this came an increased importance of municipal buildings as a symbol of civic pride by which the character of a cities population was judged.2

Burlington was no different than any other burgeoning community in wanting a City Hall that would both impress visitors and entice businesses to utilize their facility for conferences, hosting popular entertainers, or other large gatherings which could potentially bring additional income into the community. The easiest way to achieve this goal; build a new City Hall that would represent the Burlington its leaders wanted it to be.

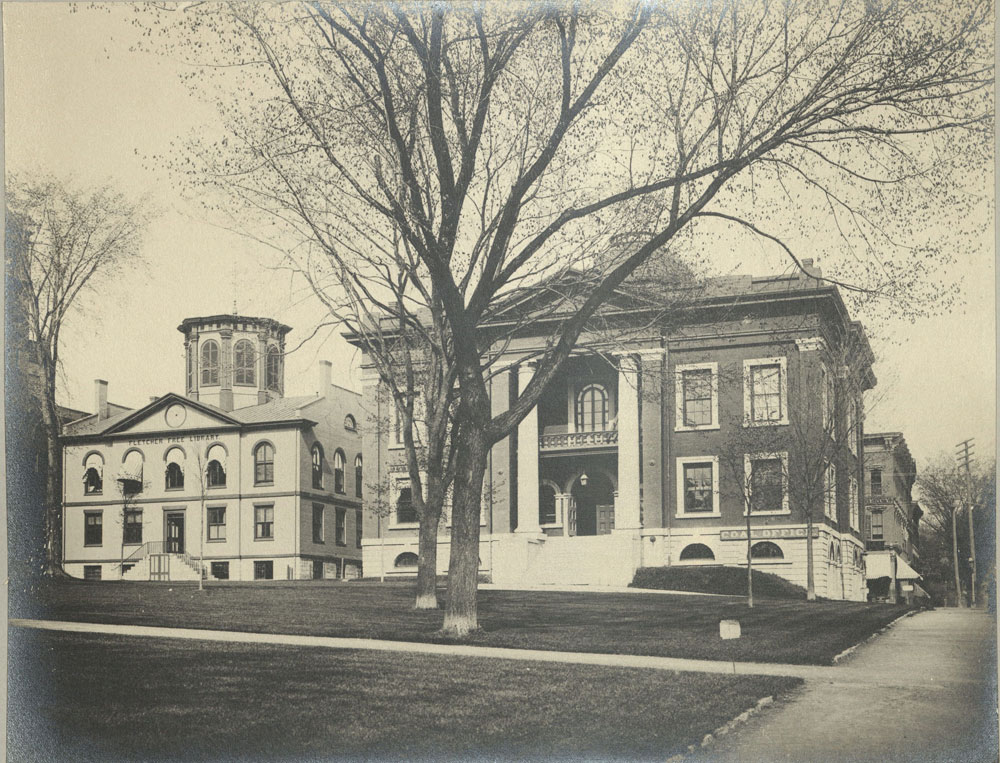

The road to building a new City Hall for Burlington was long and fraught with many hurdles, the first being what to do with the old City Hall? Erected in 1854, eleven years before Burlington officially became a city, the old building was a sterling example of the technological advances of the time.3 It was a grand building with massive columns flanking its western facing portico (see Fig. 1) and was reputedly admired by famous architects of the time.4

Unfortunately time had not been kind to the historic building and it was not able to keep pace with the rapidly changing world around it. Maintenance expenses incurred to keep the building up and running were excessive and becoming more and more difficult to rationalize. The building had fallen into such a state of disrepair it was reported by John Southwick, “bricks fell from the edge of the roof to the ground in imminent danger of striking the heads of passersby.”5 It was speculated that more money had been spent on repairs and trying to upgrade the building with modern amenities than was spent on its original construction.6

There were also issues with the size of Old City Hall. Many bids to host conferences and speaking engagements were being granted to communities such as Montpelier and Rutland instead of Burlington because they had facilities with large auditoriums, which easily allowed for large gatherings. This was a point of contention for local politicians and community leaders who began lobbying heavily in the early 1920s for construction of a new facility, which would provide Burlington with a renewed competitive edge.

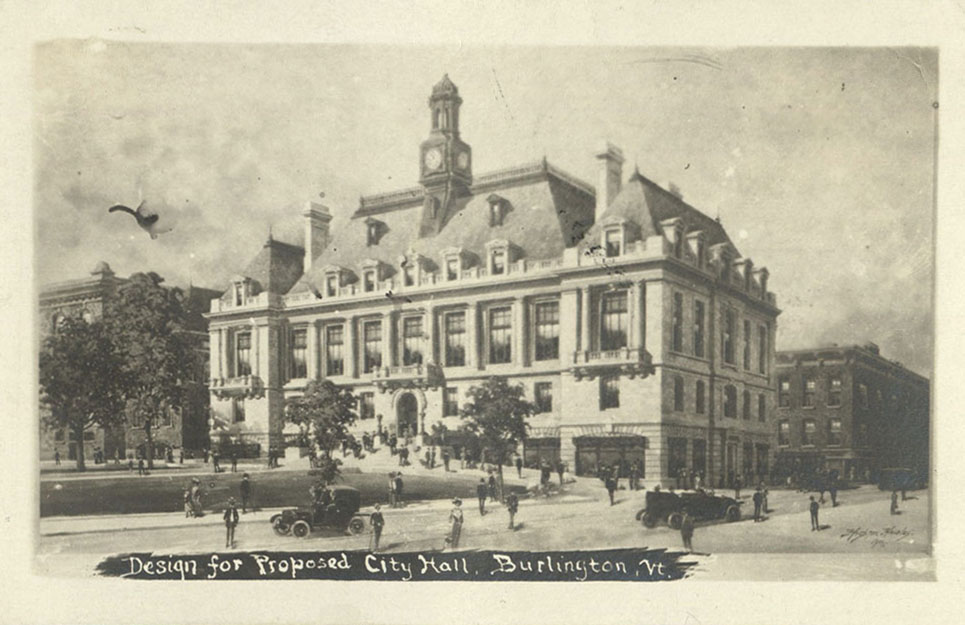

While the belief that a new City Hall facility was necessary seemed overwhelmingly popular, there were some who objected to its proposed location and the demolition of the old City Hall building, the Stannard Memorial building and the No.1 Fire Station. There were those who lobbied to have the new facility relocated to a different area of the city to avoid loosing three important structures and such a proposal was seriously considered. Issues with ground stability and the capability of the area of potential relocation to handle the load necessary to support a new facility of adequate size effectively ruled out relocation. Another potential problem stemming from relocation of the new building was comparable rent prices for planned commercial space within the structure. Rental rates for the central downtown area were considerably higher than in other areas of the city, which would provide more income per square foot for rentable space.7 This was a crucial factor in the planning the new facility as it was the hope of the Board of Aldermen and the Advisory Board that the building be as financially self sufficient as possible. These two issues, along with the fact that old City Hall was not able to keep up with the growth of the city, new technological advances, or its own physical deterioration in ways that were needed at the time effectively sealed its fate. Initial designs for the proposed Burlington City Hall were printed out as postcards and distributed showing a sizeable and ostentatious building standing where old City Hall and Stannard Memorial buildings once stood (see Fig. 2).

Even though building a new facility had been a dream of community leaders for quite a while, the realization of these plans came with a hefty dose of reality. The first step in planning for construction of a new City Hall was to identify exactly what would be required of the new building. They wanted a facility that was pristine and new with state of the art technology integrated. Increased use of telephone and wireless radios make keeping up with the rest of the country, and even the world, a basic necessity of municipal buildings in the 1920s. The building needed to be able to house large gatherings, making Burlington competitive with larger facilities in other Vermont cities. It also needed to be able to keep up with the demands of the rapidly growing city while still being able to contribute to its own financial support. The new proposed facility was to contain an auditorium large enough to host gatherings of 3,000-3,500 people, which was more than any other facility in Vermont at the time and would give Burlington a huge advantage over other cities vying for conference bookings.8 New City Hall would also provide ample office space for civic workers which were severely overcrowded in the existing building to the point that some offices, such as the City Court, were forced to relocated to other facilities able to provided them with much needed space.9 This issue tied into another problem Burlington would have to face; where were the remaining offices located in City Hall going to be relocated until construction was complete? This issue was so prevalent that suggestions for possible areas of temporary relocation were solicited from citizens of Burlington via the press. Letters to the editor in response suggested retrofitting portions of the City Water Department facility to house a Municipal City Court Room.10 Eventually it was decided that municipal offices not already relocated would be temporarily moved into the old Junior High School building during the construction period.11

The war contributed, though not in an altruistic way, to stimulation in tech industries and chemical manufacturing which assisted in boosting the American economy.12 The emergence of strong new industries, along with the popularization of assembly line manufacturing changed the industrial landscape of the nation. The growth of industrial manufacturing led to a surge in urbanization. People in rural areas were leaving behind farm life and heading to cities like Burlington looking for work. The 1920s marked the first time in American history that a majority of its population was urban rather than rural.13 With increased pay from industrial and commercial work came an increase in buying power. The rise in popularity and affordability of the automobile opened up new avenues of growth in Burlington. The rapid assimilation of the automobile into normal family life also led to a decline in use of public transportation such as regional trains and electric streetcars.

The economic atmosphere of the 1920s also had a lasting effect on the design and construction of the new Burlington City Hall facility. The First World War ended with the former global financial leaders in dire straits leaving the United States as the new center of financial power. The war transformed our country “from a debtor nation to a creditor nation”making the American financial market the most dominant in the world.14 Unfortunately, with this shift in the market came the emergence of speculation and other get rich quick schemes ultimately contributing to the financial crisis that rounded out the decade. For the first time common Burlingtonians were able to utilize credit as a purchasing tool which allowed them a new found sort of financial freedom to invest in not only consumer goods but stocks and bonds as well. The city needed a municipal building to reflect the emerging prestige of its citizens.

On the other side of the law, prohibition was an inadvertent contributor to the burgeoning economy of Burlington and the surrounding area in the 1920s. Though Vermont had been primarily a dry state by choice since 1847, when the 18th Amendment took effect in January 1920 Vermonters found themselves caught up in an emerging industry ‘pitting rumrunners and revenuers against each other’.15 Proximity to Canada with its multitude of small, generally un-policed rural roads as well as its location on the banks of Lake Champlain made Burlington a hotbed of booze smuggling activity. During prohibition the average Canadian purchase of alcohol increased from 9 gallons to 102 gallons per year, the extra being transported illegally into the US via back roads and clandestine boat rides.16 This side business proved quite lucrative with those willing to take the risk, earning a month’s honest pay with one night of illegal smuggling. The fact that so many people were able to afford automobiles the temptation of fast money proved too much for many resulting in an overcrowding of penitentiaries with those interned for Prohibition violations. All in all expenditures on federal prisons increased more than 1,000 percent during this time.17 It was a new world of independent and highly mobile citizens emerging and Burlington’s municipal operations were struggling to keep up with the increase in ‘traffic’. Socially there were many changes occurring in 1920s Burlington that had a profound effect on the design of the new City Hall as well. The emergence of women as a force in not only politics but the work place as well, called for rational changes in the design of the building that would not have been considered only a decade earlier. Before World War I there were very few women found in the workplace in a non-domestic capacity, but with many of the young men off fighting in Europe it was women who stepped in to fill the gap. Organizations such as the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) saw this as an opportunity to target some of their non-temperance programs such as women’s suffrage, education reform and equal rights in the workplace. It became a point of contention that public buildings, many of which women were both frequenting and working in, were lacking in facilities for women. This was so evident in Burlington that City Council established an official Rest Room Association and set aside budgetary funds for establishment and maintenance of restroom facilities for women. By 1920 the need for women’s facilities had increased so much that additional funding was requested by the Rest Room Association in order to keep up with demand.18 It was becoming apparent to city officials that allowances for women’s facilities needed to be considered in the new City Hall building design.

Factoring in the changes in economy, politics and social stations taking place in 1920s, Burlington city leaders needed a central municipal building that would not only keep with the times but would be forward thinking. They needed a City Hall that would weather the cultural changes they were going through and maintain its symbolic stature as a beacon of social advancement in the community. It needed to not only provide a centralized location for municipal offices but also needed to be expansive and versatile enough to allow for growth. It should cater to all of its citizens, not just men, and represent the brightness of Burlington’s future as a cultural and financial center of the state of Vermont. Here began the task of trying to assimilate rational needs with symbolic aspirations and transform them into a cohesive, functioning public building without placing an unmanageable financial burden on the community.

In 1925 the needs of a new City Hall for the expanding community of Burlington became so apparent that a decision was made by Mayor C. H. Beecher and the Board of Aldermen to take action. On October 14, 1925 proposal for construction of a new City Hall requiring $750,000 bond19 was put to public vote and passed with overwhelming majority. By early November plans had been finalized to make necessary alterations to the old Junior High School building for use as interim City Hall during the construction process and the emptying of Old City Hall and Stannard Memorial building had begun.20 It wasn’t until December of 1925 that questions began to arise from the public about the proposed building. It was intimated that location of the large auditorium, one of the main reasons for constructing a large new facility, would be shifted from second floor to third while placing office floors below. Adjustments were also made to the original plan effectively eliminating the commercial use of the lower floor, which was touted as a means to make the building self-supporting. This change was due in part to the fact that after passing construction bond it was disclosed that the facility could not be as large as previously planned without significant increase to the approved budget.21 Unfortunately the building would be different in design and smaller than planned, but on the other hand that meant No.1 Fire Station was no longer slated for demolition. At this point it became apparent to the public that they had voted in a $750,000 bond for construction of a new city hall facility before reviewing the architects final design proposal.

The second major blow came at the hands of former Burlington City Mayor James E. Burke when he raised complaints about the budget and design of the new City Hall project in a public hearing held January 29, 1926.25 At that time Mayor Beecher rebutted complaints about the design of the building and reassured the Board of Aldermen and all in attendance that the City Hall project was not only well within budget, but $150,000 of its bonds were available for separate appropriation for construction of a new memorial hall which will solve the issue of diminished seating capacity in the new City Hall auditorium. The Board of Aldermen determined that they would follow the advise of the architecture firm of McKim, Mead & White as they were the most qualified to confirm the feasibility of these plans. Per their recommendations the project ensued as proposed and construction on the new City Hall building resumed after the spring thaw.

Official bids for construction of City hall were reviewed in spring of 1926 with James E. Cashman Construction and Spear Brothers being lead contenders. Unfortunately Spear Brothers miscalculated construction costs resulting in an increase in their proposed bid by around $100,000, effectively removing them from the competition.26 Cashman, a local contractor whose services were frequently used for public works projects and who was employed for demolition of the old City Hall facility and Stannard Memorial building, was officially granted the construction contract on July 21, 1926.27

By this time it had been decided by the Board of Aldermen and architecture firm of McKim, Mead & White that the total bond of $750,000 passed for construction would be split out between construction of the smaller City Hall facility ($500,000), a new Memorial Hall building with large auditorium capacity ($150,000), and a new Central Fire Station ($100,000). With Mr. Cashman’s bid coming in at $358,182 there were remaining funds of $141,818 to cover additional costs of upgrades including the replacement of wooden pilasters called for in the design with pilasters made of Vermont Marble, costing an additional $26,300. 28 Consuming a large portion of the remaining funds were contracts for plumbing, awarded for $17,169 to Blodgett Company, and heating and ventilation, awarded for $16,340.98 to Frank S. Lanou & Son. Both Blodgett and Lanou & Son were local Burlington companies like Cashman, which helped inject constructions funds back into the community from which they had originated.29

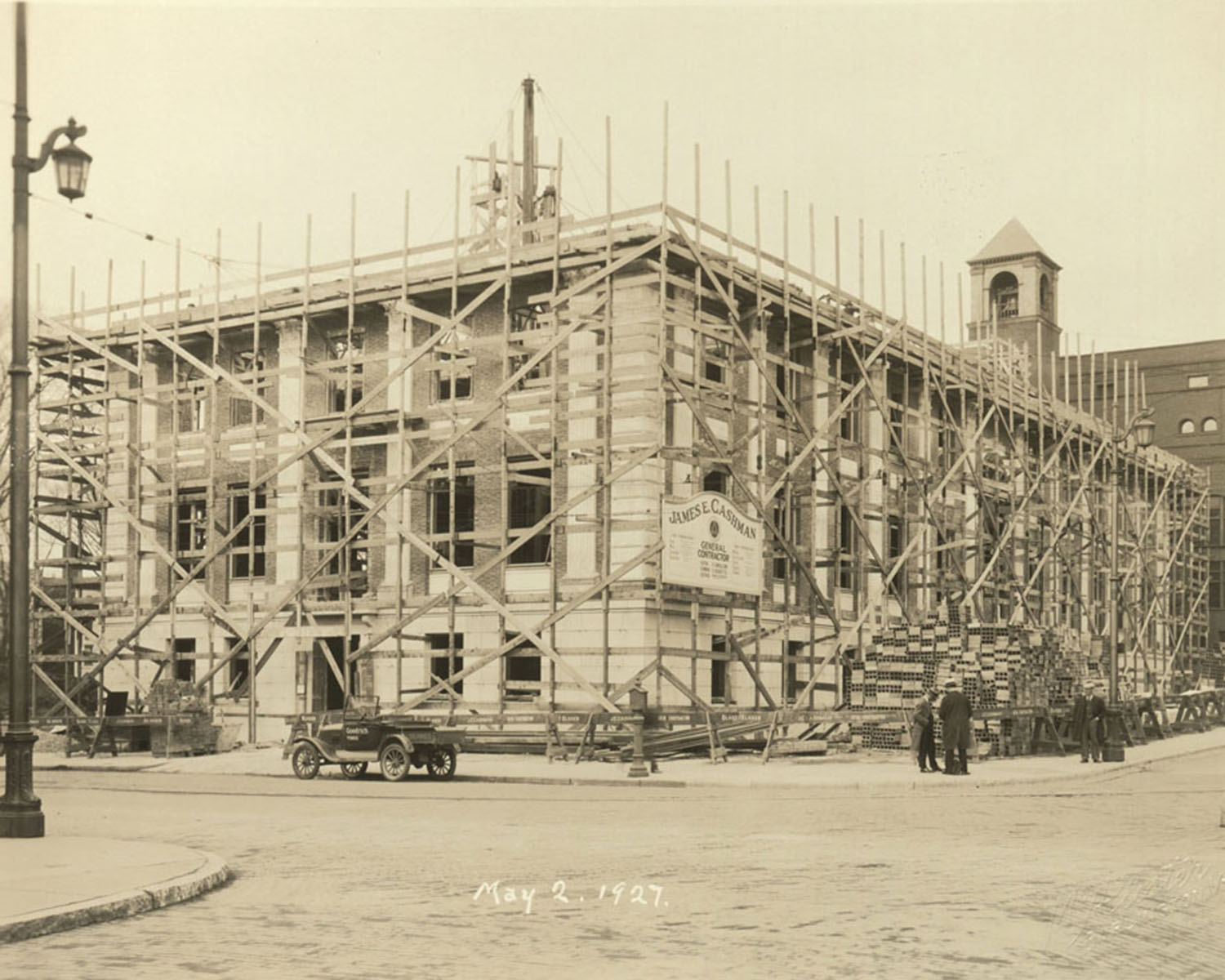

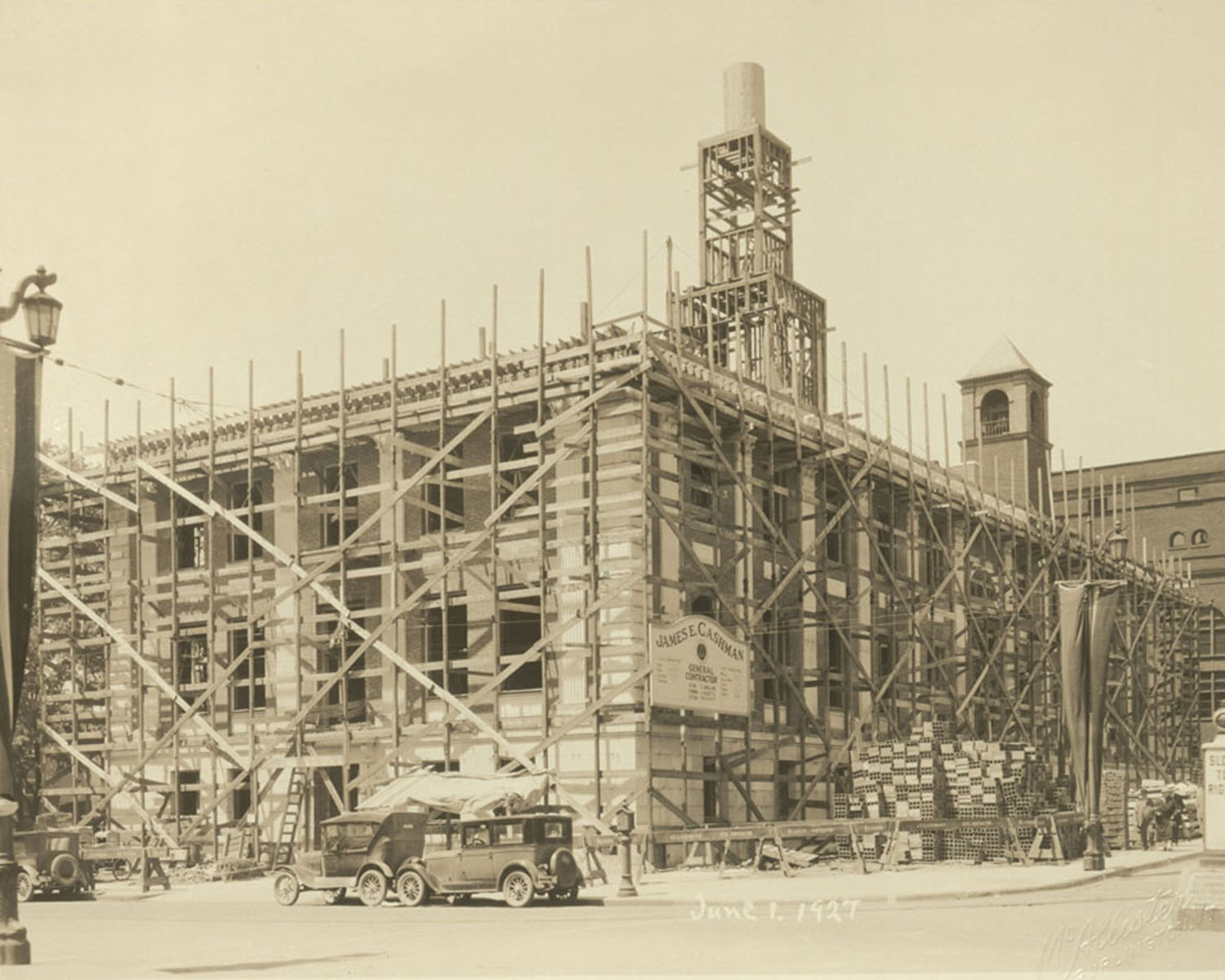

Once contracts were finalized and schedules set, construction was free to begin. In July 1926 Cashman rolled in the heavy equipment and began excavating the area beneath the old City Hall and Stannard Memorial buildings, creating a unified area for utilities and foundation (see Fig. 3). At the time it was estimated that construction of new City Hall would be complete by the end of 1927 with only finishes remaining after September of that year. When work began on the foundation of the new municipal building it was more than just the beginning of a project. The workers were laying the foundation of a new Burlington; they were helping construct a symbol of their community’s status as a leader in Vermont society (see Fig. 4).

There was a sense of pride in the fact that they were taking part in a project designed for the betterment of their community. In spite of this sense of civic pride Burlington had for the construction of the new City Hall building the process was not without issues. After completion of the building’s foundation, work began on construction of the steel frame skeleton that would support the body of the three-story structure. On Saturday, December 18, 1926 a steel girder fell when being lifted into place crushing a worker.30 Hersel G. Mosier, the man killed, came to Burlington from New York seeking work a year earlier following the death of his wife. Reports stated that the girder was to be used as a part of the auditorium floor support system and was being lifted into place when it began to swing, striking Mosier in his lower back killing him instantly.31

By spring 1927, after snow thaw, it was back to work as usual and progress was made by leaps and bounds. In March granite exterior walls of the first story were completed and steel framework continued (see Fig. 5).

By May, most of the exterior masonry work had been completed including red brick with granite trim and quoins as well as the upgraded Vermont marble pilasters. The weighty windowsills had been installed but the building was not yet fully enclosed, missing doors, windows and roof (see Fig. 6). By June the cupola had been framed in and attic subfloor installed, effectively closing in the third floor from open air above, and basic framework for the permanent roof had begun (see Fig. 7).

Windows and doors were still missing which kept the structure open to the elements. By August 1927 exterior masonry work was complete and the roof was intact. Finishing trim work was being done on the cupola as well as the doors and windows of the building. Pediment above the second story south facing center bay was complete but iron railings had yet to be installed. Electric streetlights, traffic lights and lines for the electric trolley had been installed and work on the granite steps leading to the east and west entrances was in full swing.

At this time windows and doors were still missing but interior work progressed as planned with boards being used to keep out the elements. When September rolled around exterior trim work was complete with the exception of the cupola and remaining ironwork (see Fig. 8). The large clock ordered from E. Howard Clock Co. for installation in the bell tower had not yet been installed but had been paid for in full.32

Progress was steadily being made on the new City Hall and though it was obvious that the proposed deadline of years end 1927 for completed construction would not be met, November 1927 brought about a setback that could have been foreseen by none. On the afternoon of November 4, 1927 massive flooding of the Winooski River and other waterways wreaked havoc on the area, effectively cutting the city of Burlington off from the outside world with the exception of limited telegraph and telephone circuits still open to neighboring Rutland.33 Washed out bridges in the immediate area left few dependable means of egress for Burlingtonians looking to escape the floods other than to travel across Lake Champlain into un-flooded areas of New York. Damage to the area was costly and repairs to bridges and roadways necessary to get the community running again took precedent over other construction projects. City officers also recognized the financial implications of flood damage and maintaining established budgets on active projects such as City Hall construction was more crucial than ever.Final construction and finish work continued throughout the winter months and into spring 1928 without major incident and was completed early that summer.

On May 12, 1928, the new Burlington City Hall was officially opened to the public and was promptly touted the crowning jewel of the city.34 Total costs for construction of the facility was $475,000 coming in $25,000 under budget and allowing those extra funds to be transferred to the ongoing Memorial Hall project. 35The three story municipal building was described by an architect from designing firm McKim, Mead & White as having “the same classical principles which inspired the public buildings of the Colonies and the early Republic, and which have formed the basis of a fine building tradition throughout New England”.36 The red brick exterior of the second and third floors rose up from the granite blocks of the first floor, decorated with Corinthian pilasters of marble, materials being locally sourced. The building was roofed with slate tiles, also locally sourced, and topped with a wooden cupola housing an east/west facing clock and bell that rung the hours (see Fig. 9). The main entrances of the building were east/west facing and entered the structure on the second floor. These entrances featured large granite steps, the western steps measuring 48’ wide, both with cast iron decorative railing.37 These main entrance doors were grand and embellished with ionic columns and leaded glass fanlights trimmed in marble and featured the Burlington City coat of arms (see Fig. 10). A smaller north facing entrance pierced the building on the first, or ground, floor and was trimmed in granite. Most materials used in construction, from foundation to roofing were sourced locally in Vermont.38

The interior of the building was described as being equally as grand as the exterior. The main hallways were tiled with Vermont marble flooring and wainscoting (see Fig. 11). Local marble was also used to construct the main stairs (see Fig. 12), which were flanked by cast iron balustrades topped with mahogany rails. Floors of individual offices were polished concrete with the auditorium floors being clad in maple, giving it a warm feel. The building contained nine vaults located in municipal offices for storage of important documents, all containing janitor calls allowing anyone accidentally locked inside to call for assistance.39 Each entrance to the building displayed a directory to assist visitors in locating the office of their choice. An important aspect of the interior design was utilization of space.

Each office in the building contained separate working spaces and public space, as well as a coat closet, not only a convenience but also a way to minimize clutter. Furnishings inside the offices were mainly constructed of steel and aluminum allowing for durability as well as increased fire safety measures.

The ground floor held the offices of the Burlington Light Department, Water Department, Parks Department and Charity Department. This level also accommodated the boiler room, transformer room, storage as well as unassigned room space designated for future growth. The corridor floors on this level were alternating green and white terrazzo and vestibules had Vermont marble wainscoting.40 Radiators on this floor were described as being covered by decorative bronze grills. The ground floor also contained a fully functioning electric kitchen with dumbwaiter leading to upper floors and restrooms for both men and women.

The second floor of the new Burlington City Hall was where one might find offices of the City Clerk, City Treasurer, Health Department, City Mayor, as well as the main floor of the auditorium, ticket office and coat check room. The auditorium ended up being even smaller than planned with seating capacity of 700 but proved to be very versatile in design in that seating on its main floor was movable.41 Designers chose to have the main east and west-facing entrances to the building enter on the second floor rather than the first to help facilitate public access to the most commonly used areas of the building like the auditorium. Restroom facilities for both men and women could be found on the second floor as well.

On the third floor were located offices of the Street Department, Assessors Office, Building Inspector, a City Council Room, Committee Room and balcony section of the auditorium. On this floor you would also find restrooms for men and women, a men’s smoking room and additional unassigned rooms for anticipated future growth.42 The auditorium balcony level located on this floor contained a small projection room, which made the facility capable of being used as a movie theater. The third floor also housed a wrought iron staircase leading up into the cupola housing the clock and bell.

One of the most impressive aspects of the new City Hall facility was the utilities arrangement. Over one mile of piping was used in the building, all covered to prevent sweating, and none of it visible in any of the offices or public spaces.43 A four-foot deep crawl space was constructed below the building to house all of the piping and electrical conduits needed to make the building run. Even heating pipes used in the overhead steam heating system were hidden in chases so as to hide them from sight. The building was built for public use and contained 21 toilets, 27 lavatories and three public water fountains. It also hosted nine internal hose cabinets for emergency fire services. When the buildings plumbing was installed it was sectioned off into different divisions with individual valves for each allowing for repairs to a particular section without disturbance in water service to other parts of the building. Burlington’s new City Hall was boasted as having the best plumbing system north of Boston.44

Overall the building was considered a success and quickly established Burlington as a cornerstone of progression in Vermont. The ability of the city council and those involved in its physical construction to adjust plans in a way which allowed the facility to be adapted to suit all of the needs set forth in the initial proposal is something to be admired. By reducing the size of City Hall and designating a separate location for construction of a Memorial Auditorium capable of hosting large functions they not only diversified Burlington’s downtown, but also were able to quell some of the upheaval resulting from demolition of Stannard Memorial building. The smaller footprint of the final City Hall structure also allowed for retention of the No. 1 Fire Station, a historic building still standing in downtown Burlington today. On the other hand timing turned out to be a double-edged sword that city officials were forced to contend with at the close of the decade. Completion of Burlington’s new municipal building in May 1928 was little over a year and a half before the stock market crash of October 1929, which halted similar projects in their tracks throughout the country. While the city was in luck to have a finished structure available for use, they were then faced with the difficulty of repaying bonded funds during the worst financial crisis of our nations history. The economic crash was felt throughout Vermont in terms of unemployment and falling prices in agriculture,45 but its ramifications were compounded by financial responsibilities placed on citizens due to increased taxes. Not only were city taxes in Burlington increased to cover the expected costs of bonded construction projects, but state taxes were also increased at this time to pay for damages incurred during the flooding of November 1927.46 As difficult as the added financial strain proved to be, not only did Burlington survive but continued to thrive throughout the years. This success has continued making Burlington the social and cultural hub of Vermont it is today and City Hall still stands as a representation of the perseverance of the community through an era characterized by unique and extreme failures and achievements (see Fig. 13).

NOTES

2. John L. Southwick, "A City Hall That Will Be The Pride of Burlington," The Burlington Free Press and Times, September 4, 1925, 4.

4. Southwick, “A City Hall That Will Be The Pride of Burlington”, 4.

5. Ibid.

6. Southwick, “Burlington’s Evolution From Town to City”, 4.

7. John L. Southwick, “All Sides of Burlington’s City Hall Project,” The Burlington Free Press and Times, October 9, 1925, 4.

8. Southwick, “A City Hall That Will Be The Pride of Burlington”, 4.

9. “Looking For Home For Municipal Court,” The Burlington Free Press and Times, May 30, 1925, 6.

10. Louis E. Peterson, “Two New Central Locations for Burlington’s City Court Proposed,” The Burlington Free Press and Times, August 27, 1925, 5.

11. “Preliminary Plan for Burlington’s New City Hall,” The Burlington Free Press and Times, December 3, 1925, 2.

12. Payne, 20.

13. Ibid., 45.

14. Ibid., 17.

15. Scott Wheeler and Christopher Bray, Rumrunners & Revenuers: Prohibition in Vermont (New England Press, 2002), 21.

16. Ibid., 9.

17. Ibid., 28.

18. Fifty-Sixth Annual Report of the City of Burlington Vermont for the Year Ended December 31, 1920 (Free Press Printing, 1921), 170.

19. Sixty-First Annual Report of the City of Burlington Vermont for the Year Ended December 31, 1925 (Free Press Printing, 1926), 211.

20. “Temporary City Hall,” The Burlington Free Press and Times, November 3, 1925, 2.

21. “Preliminary Plan for Burlington’s New City Hall”, 2.

22. Ibid.

23. “Proposed City Hall Project Retarded By Chancery Suit,” The Burlington Free Press and Times, January 5, 1926, 1.

24. “Mayor Beecher Declines to Call Special City Meeting,” The Burlington Free Press and Times, January 12, 1926, 3.

25.“Aldermen Listen to Debate on New City Hall Issue,” The Burlington Free Press and Times, January 30, 1926, 9.

26. “James E. Cashman Is Selected To Construct New City Hall,” The Burlington Free Press and Times, July 15, 1926, 1.

27. “New City Hall Contracts Awarded,” The Burlington Free Press and Times, July 22, 1926, 9.

28. “James E. Cashman is Selected To Construct New City Hall”, 1.

29. “Burlington and Winooski (Vermont) Directory: For The Year Beginning June 1927,” Vol 38 (H. A. Manning Co., 1927), 449.

30. “Girder Falls Killing Man,” The Burlington Free Press and Times, December 20, 1926, 8.

31. Ibid.

32. Sixty-Third Annual Report of the City of Burlington Vermont for the Year Ended December 31, 1927 (Free Press Printing, 1928), 281.

33. “Winooski Bridge Is Carried Away By Big Flood,” The Burlington Free Press and Times, November 5, 1927, 1.

34. “Burlington’s New City Hall,” The Burlington Free Press and Times, November 5, 1927, 1.

35. “Burlington’s New City Hall Is Now Complete And Will Be Opened For Public Inspection This Afternoon,” The Burlington Free Press and Times, May 12, 1928, 3.

36. Ibid.

37. Ibid.

38. Ibid.

39. Ibid., 10.

40. Ibid.

41. Ibid.

42. Ibid.

43. Ibid.

44. Ibid.

45. Payne, 71.

46. Sixty-Fifth Annual Report of the City of Burlington Vermont for the Year Ended December 31, 1929 (Free Press Printing, 1929), 13.