Burlington's Manufacturing Heritage along the Winooski River

By Chris Witman

History Overview

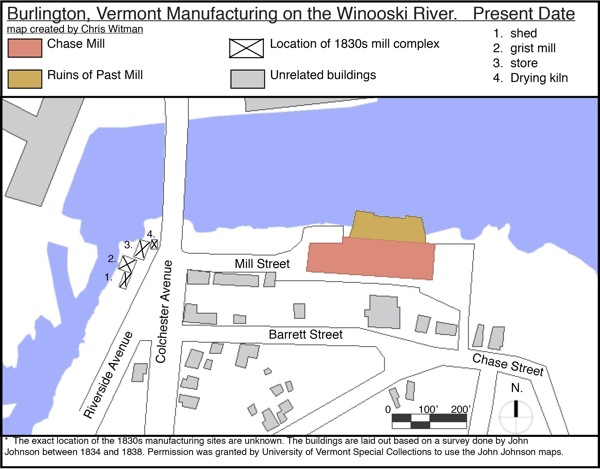

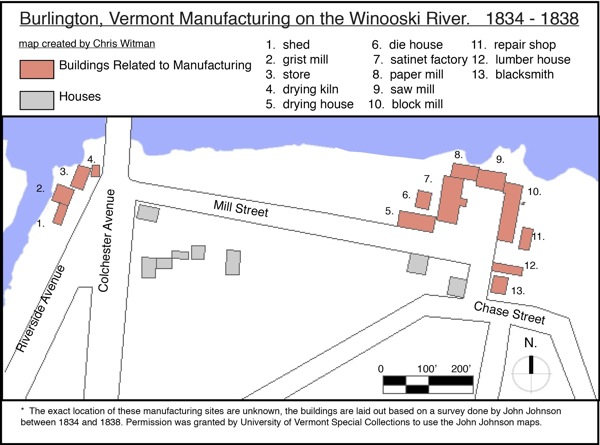

The Winooski River that separates Burlington and Winooski, Vermont had provided many industries over the years with the energy they needed to power each respective mill. The manufacturing examples that will be looked at in this section are all on the Burlington side of the Winooski River. This relatively small section of land that is between the river and what is now Chase Street has seen from the early 19th century to the mid-20th century relatively large alterations to the built environment. These dramatic alterations in the location that is given didn't always come from the willingness of the owners and operators of the mills. They came mostly from natural disasters like floods or fires that would start in one mill and spread to the neighboring properties.

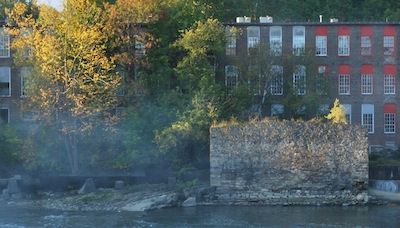

This small northeastern area of Burlington has seen important locally significant manufacturing companies run by such entrepreneurs as Guy and Moses Catlin, Alfred and Dan Day, William Vilas, and Morillo Noyes. It has witnessed the rise and fall of the short-lived Winooski Patent Block Manufacturing Company; with the help of its innovative machinery it could have challenged any ship block industry in America during the mid-19th century. Over time, an area of many small mills had turned into an area that is controlled by mainly one. This one mill, the Chace Mill, is the only one left on the Burlington side that used the energy from the Winooski River. The Chace Mill stands over almost all other traces of the milling history in this area of Burlington, but the site's history tells a story of creative and visionary people and their drive to harness the powerful but dangerous forces of the Winooski River.

Although the Chace Mill is the only one left standing in the area that will be studied, knowledge of past milling endeavors must be looked at to fully understand the history of this site. One must first start with the two men who first had a hand in the creation of the manufacturing history in this area and their mills. Guy Catlin and his brother Moses Catlin were the dominant figures in this part of Burlington during the early parts of the 19th century. Moses Catlin was originally from Litchfield, Connecticut. He was the husband of Lucinda Allen, a relative of Ira Allen. Moses Catlin's wife sued Ira over a land dispute that started after the death of her father. Out of the lawsuit, Lucinda and Moses Catlin acquired the land around the "Onion River" (which is now called the Winooski River), plus $46,847.80 dollars, thanks to a decision by the federal courts.1 Moses Catlin and his wife moved to Burlington shortly after to take advantage of Lucinda's inheritance. Moses's brother, Guy Catlin, followed the couple and started a grist mill with Moses that was in operation around 1812.2

In the mid-19th century, Winooski, Vermont was home to some of the state's largest and most innovative manufacturing companies. Located just north of Burlington (and part of the town of Colchester until being incorporated as a separate city in 1922), Winooski offered mill owners ample land, railroad access, and most importantly, water power from the Winooski River. Together, the mills and factories on both sides of Winooski Falls helped to shape Vermont's industrial heritage.

Notes (Overview)

Area Timeline

Timeline of Manufacturing

1812 – Flour production started at the grist mill located at Winooski Falls to the left of the Winooski Bridge on the Burlington side.

1814 – Yarn production started at the satinet factory and around 1836 worked with merino wool around 1 Mill Street, Burlington.

1814 – Paper production started at the paper mill located on Mill Street around where the Chace Mill is today.

1818 – Linseed oil production started at the oil mill located at Winooski Falls to the left of the Winooski Bridge on the Burlington side.

1820 – White pine lumber production was started around this date at a saw mill around 1 Mill Street, Burlington.

1830 – Flood destroyed the grist mill located at Winooski Falls to the left of the Winooski Bridge on the Burlington side.

1832 – Vacancy, the paper mill around 1 Mill Street, Burlington.

1834 – Construction was started on a new grist mill that is shown in the John Johnson collection at University of Vermont Special Collections. It was located at Winooski Falls to the left of the Winooski Bridge on the Burlington side.

1836 – Ship block production started at the block factory around 1 Mill Street, Burlington.

1837 – Plaster of paris production possibly started at this time at a plaster mill located at Winooski Falls to the left of the Winooski Bridge on the Burlington side.

1838 – Fire destroyed the statinet factory around 1 Mill Street, Burlington.

1838 – Fire destroyed the saw mill around 1 Mill Street, Burlington.

1838 – Fire destroyed the vacant paper mill around 1 Mill Street, Burlington.

1838 – Fire destroyed the block factory around 1 Mill Street, Burlington.

1846 – Vacancy, the oil mill located at Winooski Falls to the left of the Winooski Bridge on the Burlington side.

1846 – Cotton material production started at the now vacant oil mill, located at Winooski Falls to the left of the Winooski Bridge on the Burlington side.

1852 – Fire is the probable cause of the destruction of the plaster mill around this time. It was located at Winooski Falls to the left of the Winooski Bridge on the Burlington side.

1852 – Fire destroyed the oil mill, now being used by the Winooski Mill Company. It was located at Winooski Falls to the left of the Winooski Bridge on the Burlington side.

1852 – Construction started on a new cotton mill building around 1 Mill Street, Burlington.

1859 – Fire destroyed the grist mill, located at Winooski Falls to the left of the Winooski Bridge on the Burlington side.

1859 – Construction started on a new grist mill located at Winooski Falls to the left of the Winooski Bridge on the Burlington side.

1891 – Fire destroyed the cotton mill around 1 Mill Street, Burlington.

1891 – Construction started on what is called the Chase Mill on 1 Mill Street, Burlington.

1926 – Vacancy, the grist mill at Winooski Falls to the left of the Winooski Bridge on the Burlington side.

1926 – Vacancy, the Chace Mill on 1 Mill Street in Burlington.

1927 – Flood destroyed the grist mill at Winooski Falls to the left of the Winooski Bridge on the Burlington side.

Grist Mill History

What is known about the first grist mill from 1812 that Moses and Guy Catlin owned, is that a 1820s manufacturing census states that there were five men working in the grist mill at $400 dollars a year.1 The location of the original site today is just downstream of the lower dam on the Burlington side of the Winooski River between the bridge and the corner of Riverside Avenue and Colchester Avenue. Here one can still see part of a foundation that was part of a later grist mill. After a disaster a new grist mill was built on top of the old foundation of the original mill. When the first grist mill was built, the dam was located farther upstream. Guy and Moses would have studied the water and designed their mill in a way that could maximize the power of the Winooski River. This was done by finding out what was called the "head" and "fall". The head is the distance that water drops before it hits the wheel, and the fall is the action of the water turning the water wheel. The larger these distances are, a greater amount of energy could be created. The water would be channeled out of the river using a flume; this would allow the workers to control the flow of water. It's hard to say what kind of wheels were used at this site but different wheels had better efficiency. The overshot wheel was the best, reaching 75% efficiency.2 Pictures show that the wheel was probably inside the main exterior wall. The Catlin brother's first mill, which was made out of a stone foundation with brick for its three upper floors, was susceptible to floods considering its location. In 1830 the Winooski River flooded and wiped out the mill.3

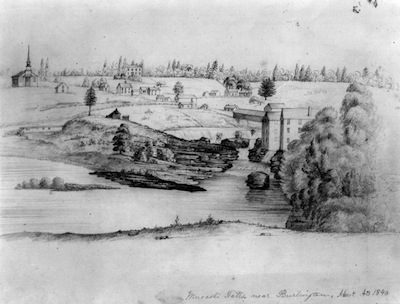

In the University of Vermont's Special Collections, in the John Johnson Papers, there is a description from 1834 of the second grist mill that the Catlin's built after the flood that destroyed the first in the same location. It had a simple rectangular plan, 36 by 44 feet, with the 36 foot elevation running along the river. Connected to the property was a shed south of the grist mill. It was 45 by 20 feet, and its 45 foot side ran in line with the grist mill's east elevation facing what is now Colchester Avenue. Upstream four feet from the grist mill was a store that was owned by the Catlin brothers. This store was two-and-a-half stories and was 30 by 50 feet. Farther up the river at an angle, running off of the store's northeast corners was a drying kiln. A drawing done in 1840 shows a sketch of what the mill looked like. It would have been a simple three story gabled building with the gable facing the Winooski River. It looks to be two bays wide on the rivers side. In the sketch there are two buildings, the one farther downstream could be a depiction of a plaster mill or oil mill that is mentioned below.4

Between 1840 and 1859, alterations probably occurred to the grist mill and the surrounding properties. This assumption is based on a reference to a five-story grist mill on the site that was mentioned in 1859, when a fire was started around 6:30 am in the lower story of the mill. The Burlington Free Press wrote that men tried to put out the fire using buckets. When the firefighters got there, one group had to cut holes through the frozen river to help fight the flames.5 At this point, Moses Catlin had been dead for about 17 years and the mill was operated and owned by H.W. Catlin.6 After the fire, H.W. Catlin built another mill on the same site. This would possibly be the fourth grist mill on this site since Moses and Guy Catlin. The Burlington Free Press stated that this new mill, which the start of construction was only 38 days after the fire, was larger than before and "the best mill in the state". The newspaper wrote the "interior finish of principle room equals that of an elegant church paneling painted white and glossy rails and trim of mahogany pillars of dark ornamental wood". H.W. Catlin's new mill was said to manufacture over 450 barrels of flour a day using machines made by Messrs Edwards and Stevens, and employed 15 to 20 men. The mill at this time had grown almost four times since the early parts of the 19th century.7

This was also the first mention of a grain elevator being used on this site.8 The first elevator system to be developed in the United States was by Oliver Evans in 1755.9 There is a chance that Guy and Moses Catlin had grain elevators in their mills as well, but the grain elevator didn't change the milling process, it just made some jobs easier. Before the elevator, the grain was hoisted up to the top floor usually from the outside on a side gable elevation. On the same side there was usually a large door on each floor to allow for new machinery that the hoist would help to bring in.10 The grain was stored on the top floor because mill workers used gravity to their advantage. The grain would be poured in from above through what was called the "eye". The eye was a reference to the hole that was cut out in the middle of the two millstones that are used to grind the grain. The millstones were above the ground floor, this was because the gears that were connected to the waterwheel and powered the millstones, would be on the ground level. Grist mills would need two millstones to operate. These stones would be placed on top of each other, lying flat. The top stone was called the "runner" and the lower was called the "nether" stone. Each stone had to be "furrowed"; this was the process of cutting groves into the stone, which stretched from the center eye to the outside edge. The flat areas that are not cut are called the "land" and this was what actually did the grinding. The grain was dropped from above, into the eye where it was ground by the uncut section of the two millstones. When the grain was ground, it then followed the groves out from between the stones. The groves also allowed heat from the friction created in the grinding process to leave the center. The finished product would then fall below into a channel that would collect the processed grain. Lastly the product would be sorted by grade.11

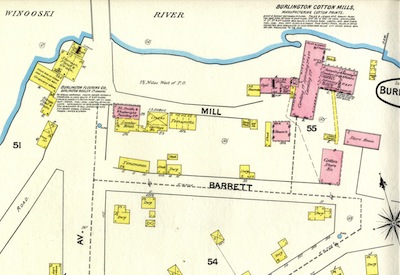

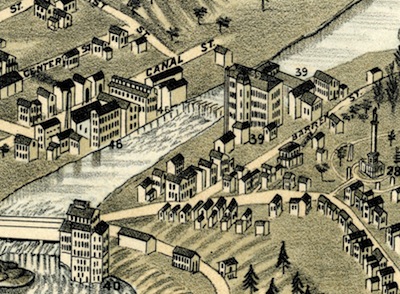

Like most businesses in this area of Burlington, owners came and went rather quickly and with little explanation. H.W. Catlin, after constructing what was said to be one of the best mills in the state, left the mill sometime before 1869, which was only ten years later. This was because of an 1869 map that is in University of Vermont's Special Collections, which shows Catlin's mill but it was now owned by the Burlington Woolen Mill Company.12 A Sanborn map from 1889 gives a description of the mill as well. This was 30 years after H.W. Catlin built his new mill so some of the features are most likely newer additions. The Sanborn map shows that the mill was primarily powered by water and steam, and includes sprinklers that would be hooked up to the city's water. The main building was five stories with a monitor roof.13 Buildings were built up around the five story structure at varies heights with their roofs sloping away from the main block. An image from an 1877 bird's eye view of Burlington shows a representation of what the mill looked like at the time it was owned by the Burlington Woolen Mill Company.14

.jpg)