|

|

|

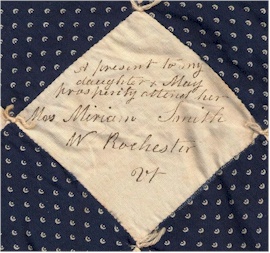

Answering the question “Who made the quilt?” is complicated. The strongest evidence we have is based on Mrs. Miriam Smith’s inscription, which reads: “A present to my daughter & May prosperity attend her.” But to which daughter of Fuller and Miriam Smith does it refer, and what is the nature of the “present?” Based on census records between 1820 and 1850, Fuller Smith and Miriam Rowell had as few as six children, three of whom were girls. The oldest daughter, born between 1815-1820 is unidentified and largely untraceable. She may have died young, or she may have married and set up housekeeping with her husband prior to the 1850 census—the first to list all members of a household by name. In any event, her name is unknown, but it does not appear on the quilt.

Two women represented on the quilt are daughters: Mrs.

Elizabeth Dyer, born in 1822, and Miss Olive T. Smith, born in 1827. At the time of the 1850 federal census,

Elizabeth Dyer and her husband Ephraim were living with their young son

within the household of Fuller and Miriam Smith in Miriam’s son But what kind of “present” was intended? When Miriam uses the word “present” does she mean that the entire quilt was a present made by herself (or by a variety of family and friends), or are the blocks alone, or even the fabric given to create them, the “present?” In other words, who actually made the quilt, and what was its purpose?

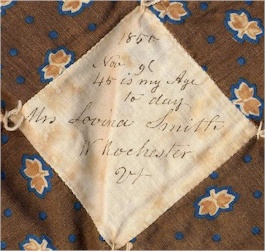

This quilt is comprised of 29 blocks set on point in a popular pattern of the time known as the Album Patch. The blocks are connected by “turkey red” sashing that crosses diagonally in rows in each direction. The entire quilt top, thus arranged, is meticulously hand stitched at a rate of 12 stitches per inch. The project, however, like many others of its kind, was never finished. At some point many years later a large print red fabric was used to back and bind the edges of the quilt, and the quilt was tied using a piece of thin flannel as batting. The binding is stitched entirely by machine. The piece was never quilted, and there is no evidence that an earlier binding was either removed or replaced. It was simply never finished by its original maker. Evidence of this also comes from inscriptions written on

other blocks. While most were written

in the same careful penmanship by a single person (probably on, or around, 09

November 1850), two blocks at least were added later: one to honor the death of Hannah J. Brown

on 05 April 1851, and another stating Mrs. Lovina

McAlister’s age of 66 years on 25 August 1852. The placement of Lovina

McAlister’s block is likewise an important piece of evidence. Today, it is cut into two halves that

appear separately in the top row of the quilt design. Since the original square had created an

uneven number, it alone would have extended beyond the top edge. In order to create a uniform shape upon

binding, it had to be cut and repositioned.

This tells us that the quilt maker and/or recipient had originally

anticipated adding more blocks to finish the row, but they never came. Eventually, the unfinished quilt

top—measuring 80” x 75”—was put aside and forgotten, until many years later

when it was finished at last. The

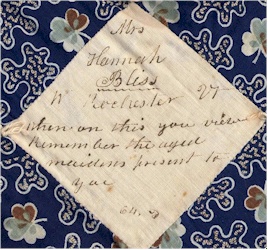

forgotten fate of the Finally, the hand stitching used throughout the quilt is fine and meticulous. There is no evidence that women of different skill levels in sewing joined together to make the quilt, even though the women named on it ranged in age between 1 and 66. It seems unlikely that young girls could have produced blocks equal to their adult relations, or that older women would have had sufficiently sharp eyesight to do the same. Yet the quilt contains 27 different cotton dress fabrics—too many to have come from one woman’s scrap bag. In this case it seems likely that each woman contributed a piece of fabric (perhaps something with special significance to her), while someone else sewed those pieces into a quilt top.

Today, “[w]e tend to visualize a woman making and signing her block to be later sewn together into a friendship quilt. Although this was a common practice there were other ways a friendship quilt could be created. Sometimes a single person collected bits of fabric from others making a block from each contribution then signing the block with that person's name.”[1][3] In short, it is possible that a daughter (or daughter-in-law) of Miriam Smith might have sewed her own friendship quilt, and that the scraps of fabrics were a “present” to get her started on a project she desired.

Yet which daughter?

Census records in 1870 indicate that Lovina

Chase Smith could read, but not write.

It seems unlikely that a friendship quilt based on signatures would

have had meaning to someone without full literacy. Sarah M. Smith’s marriage in late 1850

makes her a better possibility.

Friendship quilts were often created by young women in the time

preceding their marriage. Yet in

Sarah’s case, she had been born and raised in In addition to marriage as an inspiration for quilt-making, oral history also tells us that friendship quilts were made when women moved far from home. As Laurette Carroll notes: “Perhaps the most popular reason to make an Album quilt was because a family member or friend was moving away from the area. The recipients were presented with a finished quilt, or perhaps a quilt top or a set of signature blocks, to take with them, made by their friends or family, as a remembrance of loved ones at home.”[2][5] In Olive T. Smith’s case, she was working in the textile mills of Lowell, Massachusetts in 1850. Perhaps she was collecting blocks to remember those loved ones she left behind. There is one final factor to consider. Would a woman have signed her own friendship quilt? Linda Otto Lipsett says yes. She notes that that “quiltmaker usually included a block of her own somewhere on the quilt…” even if “she used only initials for part or all of her name.”[3][6] The names Mrs. Elizabeth Dyer, Miss Olive T. Smith, Mrs. Lovina Smith and Mrs. Sarah M. Smith, all appear on the quilt. In this case, either the quilt owner did indeed sign, or the quilt belonged to that mysterious and unknown oldest daughter of Fuller Smith and Miriam Rowell, who would have been in her early 30s at the time.

|

The physical condition of the quilt tells

us something important:

The physical condition of the quilt tells

us something important: