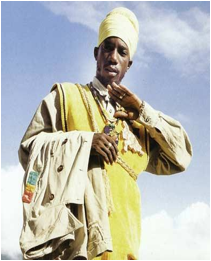

(the

images above are of reggae artists Sizzla and Capleton)

Dem Bobo Dreads

By Mark Porter Sperry

Like

all major religions, Rastafarianism has evolved since its formation. It has

thus far split into three separate factions, each with varying degrees of

devotion, varying degrees of emphasis placed upon different aspects of the

religion, and certain independent beliefs unique to each sect. The Bobo Ashanti

order is one of the three factions of Rastafarianism. These rastas, who are also

referred to as Bobo Dreads, tend to live separate from society and its

regulations, while following their own religious code as a way of life. While

Bobo Shantis generally share the fundamental beliefs of Rastafarianism with the

other two sects, for example that Haille Sellassie is god, they remain distinct

in ways as simple as they way they dress to as controversial as their radical

avocation of black supremacy. However, while some of their philosophy may seem

radical, Bobo Dreads generally conduct their day-to-day life with a tranquil

and passive disposition and are often described as friendly and courteous by

those who have interacted with them. Finally, like the other two mansions of

Rastafarianism, the message of the Bobo Shanti has a strong foothold in reggae

music due to the success of artists such as Sizzla, Capleton, and Anthony B,

and while certain areas of the Bobo Shanti ideology may be controversial to

some, it is undeniable that their message is important and that it should be

heard throughout the world.

Similar

to the Maroons, members of the Bobo Ashanti order live together in a community,

which exists apart from society. They rely on their religion to provide them

with a code of ethics and to guide their behavior, rather than the laws put in

place by the Jamaican government. However, this relative independence does not

suggest that Bobo Shantis behave in a way that the Jamaican government would

not condone, and I am sure that it is for this reason their relative

independence has been allowed to persist. This communal and tight knit way of

life is very different from the other Mansions of Rastafarianism, whose

followers tend not to place so much emphasis on community and are organized

much more loosely[1](pg. 70). The

Bobo Ashanti compound is located nine miles east of Kingston at bull bay, and

is situated atop a hill often referred to as “Bobo Hill”. However, this

sanctuary was not immediately present for the Bobo Shantis in the initial years

preceding the orders formation, and Dem Bobo Dreads had to endure minor

tribulations before settling there. “The Bobo remained at Ackee Walk until 1968

when they were finally bulldozed. They then settled at Harris Street in Rose

Town, where they were forced out to Eighth Street in Trench Town, then to Ninth

Street, and finally, to Bull Bay where they have remained ever since on the

rocky government lands overlooking the town[2](pg.

174).” In order to enter this secluded commune one must pass through an “arched

gateway,” under which each person who is recognized as a Bobo Shanti is

required to utter a prayer, whether it be spoken aloud or internally[3](pg.

172). This signifies that although Bobo Dreads still reside in Babylon, the

land that they have atop Bobo Hill, is believed by them to be sacred. Even

though the Bobo Ashanti may be the most organized and community oriented sect

of Rastafarianism, the inside of their compound is by no means a bustling

metropolis. Extensive fields of Gungu peas cover the majority of the land

within the compound[4](pg. 173).

Buildings are almost primarily houses with certain exceptions being a visitors

hut, a sick bay, and a temple[5](pg.

173). From what I can ascertain through various descriptions of the Bobo

Ashanti compound, the lifestyle there is a modest one, valuing simplicity, and

with religion being regarded as what is most important in life. In ending,

while the secluded, organized, and self-governing features of the Bobo Shanti

community set it apart from the other two mansions, core Rastafarian values are

certainly present as well, such as simplicity in life.

While

the Bobo Ashanti ideology promotes black Supremacy to the extent that

Caucasians are considered to embody what is most evil in the world, it would be

entirely false to assume that this belief entirely engulfs the character of a

Bobo Shanti. After all they are people, not vessels of hatred, but they are

people of a race who have been made to endure much suffering, and unfairness

over many years. On the contrary

Bobo Dreads are a frequently described as hospitable, friendly, and courteous

people. A simple, but notable indication of this is that two of my sources for

this paper are written accounts by social scientists that were let into the

commune, allowed to observe the lifestyle, customs, and religious ceremonies that

took place there, and then publish these observations. One of the two

researchers, whose name is Georgia Scott, is even a white woman! While this may

seem insignificant, one should not underestimate the patience and understanding

that I can only imagine is required when dealing with an outsider who is

constantly scrutinizing your life for an extended period of time. However this

is not to say that this community is open to anyone who desires to venture

inside. A Bobo priest had to interview Georgia Scott before she could enter[6](pg.

171). Upon entering she was asked if she was currently menstruating or had in

the past twenty-two days, because if so, she would be considered unclean and

would be denied entrance[7](pg.

172). Finally once she assured them that the last time she menstruated fell

within the acceptable time constraints, she was required to dress herself in

clothes that satisfied the standard dress expected of Bobo Shanti Women[8](pg.

173). After these conditions were met she was accepted as a visitor within the

village. While these formalities may appear to be strict and selective when

allowing who gets in, one must remember that this is a religious community

whose religious code is a way of life that must be upheld. As long as visitors satisfy these requirements

the Bobo Shanti will welcome most of if not all outsiders. “Out of a sample of

ninety one households there was not a single head of household or spouse living

in the area for more than six months who had not been invited to visit the

commune[9](pg.

185).”While it is safe to assume that this benevolent disposition towards

outsiders is primarily incited by what Bobo Shantis believe to be proper

conduct, their actions are not entirely selfless. For example, due to their

location atop the hill, there may be times where their wellbeing may rely on

the generosity of neighboring communities, or at least instances where it is

more convenient to ask neighbors for help. One particular instance of this is

that water is scarce where the compound is located. Therefore, by cultivating friendly relationships with

neighboring communities Bobo Dreads can rely on outsiders to assist them in

acquiring water[10](pg. 184).

Another reason that generosity could benefit the Bobo Ashanti is that will set

them apart from other Rastas who are viewed negatively or neutrally. The

results of this will not only propagate a positive stereotype towards Bobo

Shantis, as a group, as being kind or hospitable or neat, but having a

distinguishable positive identity may very well endow their religion and way of

life with an inherent merit in the eyes of outsiders. Although, the Bobo Shanti

do not let anyone, at anytime, into their community it

is undeniable that they deal with outsiders in an upstanding fashion.

A

unique practice of Bobo Shanti, which is probably, the most immediately

noticeable distinction from other sects of Rastafarianism is the way in which

they dress. Every recognized member of this order wears long robes and a turban

wrapped around their heads. The turban is arguably the most important part of

the outfit. Just as all Rastafarians wear their hair in dreadlocks in

representation of their religious beliefs, Bobo Dreads wear turbans on their

head in order to signify that they are a member of the Bobo Ashanti order. However it is not merely

worn as an a form of identification. Women must wear

their head ties not only atop their head, but have it draped over the nape of

their necks until it fully covers their hair. A Bobo Shanti woman explains the

significance saying, “Mary, mother of Jesus, wore a scarf, and so should we. We

wear our head ties simply like Mary did…. It’s not about fashion and new

styles, it’s about paying respect to Jah[11](pg.

172).” Similarly Bobo Shanti Men, whose turbans symbolize their devotion to

Haile Sellassie - who wore the turban during his coronation in 1930 – and

to Jah[12](pg.

172).” While it is true that members of the Nyabinghis, another of the three

sects of Rastafarianism occasionally choose to wear headdresses there are two

major differences between the two practices. The first is that while women in

the Nyabinghis order are required to wear headdresses, only few men wear them[13](pg.

171). The second difference is that the practice of wearing head wraps amongst

the Nyabinghis can be a fashion or style for many[14](pg.

171). While the representation of the head wraps may hold similar meaning for

both sects, the Bobo Ashanti approach is much more orthodox.

While

Bobo Ashanti’s, like all other Rastas, believe Haille Sellassie is god himself

they are also unique in that they revere Prince Emmanuel Charles Edwards as

another holy figure. Prince Emmanuel Charles Edwards founded the Bobo Ashanti

order in the 1950’s. “According to prince Emmanuel the holy trinity comprises

the three sprits: prophet, priest and king…and the priest is prince Emmanuel

himself[15](pg.

179).” This belief is justified by citing revelation 5 in the Christian bible.

Revelation 5 essentially is a story of the one who is worthy to sit upon the

throne above all, and who has the ability to open the book of wisdom. “And

I beheld, and, lo, in the midst of the throne and of the four beasts, and in

the midst of the elders, stood a Lamb as it had been slain, having seven horns

and seven eyes, which are the seven Spirits of God sent forth into all the earth[16].”

Above all else, this reverence for priest Emmanuel truly exhibits how vastly

different the three factions of Rastafari can be. This could be argued to be as

poles apart as Christians believing Jesus to be the Messiah, and Jews believing

Moses to be the Messiah.

Another

particularly noticeable way in which Bobo Dreads are unique from other sects of

Rastafarianism is the treatment towards women in their community. While it is

true that women are generally regarded as inferior to men throughout the entire

Rastafarian religion, their repressed social status within the Bobo Shanti sect

consists of even stricter regulations. One example of the mistreatment of women

in Rastafarian culture is negligence or inability for men to commit to women

they are romantically involved with. Our class witnessed this in the movie “Rockers”

where Horsemouth chooses to pursue his music career and flirt with other women

rather than invest his time and commitment to his wife and children. At one

point in the movie his wife tries to coerce Horsemouth into being a more

committed father by saying, “what about dem youths?” implying that they need a

him to be more present in their life; he merely replies “I teach dem youths

culture” implying that he does enough just by living his life. Along with this theme of negligence are

more rigid and seemingly subjugating rules towards women in Rastafarianism. For

example a woman’s main duty in life is housekeeping and child rearing, they

cannot use birth control or have an abortion, they cannot wear makeup or dress

promiscuously, they cannot commit infidelity and so on[17].

“Bobo treatment of their women does not differ essentially from the treatment

most dreadlocks accord their women. The main difference lies in the Bob’s

greater ritualization of woman’s “evil” nature[18](pg.

179).” In line with this more negative perception in which women are viewed

stricter rules are implemented dictating their conduct within the community.

Firstly, along with the robes and turbans all Bobo Shantis must wear, women

must constantly cover their arms and legs. Secondly, the rules governing

menstruation stringent then the other two sects of Rastafarianism. During

menstruation a women must withdraw herself from society and reside in the “sick

bay,” where she can be considered unclean and therefore unfit to leave for up

to sixteen day and sometimes even longer[19](pg.

177). In their daily routine and interactions, women must display and quiet and

unquestioned obedience to men in the community. While these practices may seem

despicable from an outsider’s perspective, and may even be held with contempt

by some Rastafarian women who must endure these rules, there are certainly

Rastafarian women who accept and defend them. A study was done which

essentially consisted of interviewing Rastafarian women on their apparent

social predicament. When these women were asked about their feelings on the

topic the general response was that they lived in a fair and equal system. “While

they think that a woman should look up to her man (nature set it that way),

they do not see their roles within the movement as oppressive or subservient[20](pg.

262).” When researchers posed the same question to Rastafarian men the response

was the same. Therefore while woman’s roles in Rastafarian culture, and especially

in Bobo Shanti culture where the attitude towards women is even more

conservative and stricter rules are implemented, outsiders must refrain from

interpreting this through the eyes of their own culture and realize that in

most cases Rastafarian women do not feel oppressed.

Although

concepts of black power, repatriation, and struggle against the white mans

tyranny can be found in all three Mansions of Rastafarianism, the Bobo Ashanti

tend to have a more radical approach on these matters. On matters of

Repatriation most Rastafarians, regardless of their Affiliation to whichever

Mansion, would agree that those people, or nations, who profited from the black

mans enslavement should be willing to repay black people by returning them to

Africa. However the Bobo Shantis perception of this, as well

as their attempts to bringing it to fruition, are more extreme. “The

Bobo Ashanti only differ from other Rastafari in their relentless endeavor to

ventilate the claim on the basis of international law, namely the universal

declaration of human rights and other UN conventions[21](pg.

74).” Bobo Shanti do not only believe repatriation to

be a morally binding obligation, but a legal one. Just as all Rastafarians hold

Africa as a holy land that is their home from which they have been exiled, they

also view the black race as a strong, admirable, and even hallowed people. This

perception in the black race was first asserted by Marcus Garvey, and is now a

prevalent theme in Rastafarianism. “Not only do Bobos

believe that black skin, skin blessed by the sun, is original they also

consider black women as mothers of creation[22].”

However Bobo Ashanti do not merely exercise pride in their black race, they

believe black people to be the embodiment of what is god and white people to be

the embodiment of what is evil or Satan. A sociologist by the name of Barry

Chevannes, who observed a religious ceremony that took the Bobo Shanti commune,

reflects upon some things, which the preacher touched upon. “The white man, he

explained as the reading continued, is Satan is able to create images but his

images do not have life like god[23](pg.

179).” Bobo Shantis do not just view black people in a favorable light, they perceive white people as the devil incarnate and

therefore all that is evil.

In

conclusion, The Bobo Ashanti, like the other two sects of Rastafarianism,

remain unique in many ways, whether it be their community, their style of

clothing, or even some of their radical beliefs. The most important theme that

I think can be extracted from this paper is that the Bobo Ashanti theology is

not simply comprised of hatred towards white people, which was the only fact I

heard about them prior to doing research. It is true that it is certainly an

important part of the religion, but not the only important part. For example,

SIzzla has a song “Wicked Nah Gon’ Prosper” which essentially is a song saying

that white people cannot prosper because they don’t know how to love. On the

other hand he has a song called “Thank you Mamma,” talking about how much he

loves his mother, or “Rejoice” which is all about praising Jah. So while the

Bobo Ashanti may have a radical and perhaps violent attitude towards white

people, their religion, like almost all other organized religions, is comprised

of many values, codes of conduct, and contrasting ideas and stories.

Bibliography

- Chevannes, Barry Rastafari Roots and Ideology

New York: Syracuse university press, 1994. Print.

- Jacques-Garvey, Amy Philosophy and Opinions

of Marcus Garvey New York: Arno press and the New York Times, 1968.

Print.

- Garvey, Amy

Jacques. More Philosophy and Opinions

of Marcus Garvey. Bournemouth: Frank Cass and Company Limited ,

1977. Print.

- "Mansions of

Rastafari” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mansions_of_Rastafari#Bobo_Ashanti.

WikimediaFoundation, Inc., 22 Nov. 2009. Web. 29 Nov. 2009.

- Barret, Leanard E. The

Rastafarians. Boston: Beacon Press, 1977. Print.

- Alemseghed Kebede, J. David Knottnerus Beyond

the Pales of Babylon: The Ideational Components and Social Psychological

Foundations of Rastafari Sociological Perspectives, Vol.

41, No. 3 (1998), pp. 499-517Published by: University of California Press.

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1389561

- Anita M. Barrow Reviewed work(s): Rastafari: Conversations concerning

Women. American

Anthropologist, New Series, Vol. 89, No. 1 (Mar., 1987),

pp. 262-263 Published by: Blackwell Publishing on behalf of the American

Anthropological Association Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/678865

- Scott, Georgia. Headwraps A Global Journey. New York: PublicAffairs,

2003. Print.

- "BBC - Religions - Rastafari: Women in

Rastafari." BBC - Homepage. 10 Oct. 09. Web. 30 Nov. 2009. http://www.bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/rastafari/beliefs/women.shtml

- Bentley, Sarah. "21st century Rasta 9 Features

HUCK Magazine." HUCK Magazine Surf, skate, snow, travel, music, film,

art, fashion. Web. 01 Dec. 2009.

<http://www.huckmagazine.com/features/21st-century-rasta/>.

- Benda-Beckmann, Franz Von, Keebet Von Benda-Beckman,

and Anne Griffiths, eds. Mobile People, Mobile

Law Expanding Legal Relations In A Contracting World (Law, Justice and

Power). Grand Rapids: Ashgate, 2005. Print.

- "Revelation 5 - Passage." BibleGateway.com:

A searchable online Bible in over 100 versions and 50 languages. Web.

02 Dec. 2009. <http://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Revelation+5&version=KJV>.