Sumeet Sharma December 2,

2009

Speech: Rhetoric of Reggae Final Paper

Nuclear Weapons and Reggae:

A Clash of Rhetoric

October

19th 1937 would prove to be a sad day for nuclear physics. After all, the father of atomic energy,

Ernest Rutherford, just passed

while lying on a hospital bed in Cambridge, England. By being the first to split an atom [i],

Rutherford’s research set in motion developments that would lead to the advent

of nuclear technology, weaponry and eventually war. Seven years later, on the same date; a small family would

rejoice to celebrate the birth of new member of their clan, Winston Hubert

McIntosh. This child would grow to

become reggae music’s leading emissary of his era, popularly known by the name

of Peter Tosh. By releasing his

album “No Nuclear War,” Tosh crystallized a global movement that called for the

eradication of nuclear weapons and nuclear technology with the eventual goal of

eliminating the prospect of nuclear war.

At first glance, these two men have little in common aside from the

date. One died on the date October

19th and the other was born on the same day seven years later.[ii] However the true irony of this incident

cannot be truly appreciated without understanding the rhetorical implications of

the movements that these two men participated in. The social movement that is reggae music is fundamentally

based on resisting the same power structure that nuclear weapons uphold. Nuclear weapons came with a philosophy

that justified their existence, nuclearism. Perhaps it was destined that those events on that date seven

years apart would come to perfectly characterize the relationship between

nuclear weapons and reggae: the death signifying the end of a hopeful ideology

that promised the fulfillment of new expectations for the world, the birth

alluding to the start of a new era of disappointment and struggle for the

Jamaican people, the years in between serving as a testament to the distance

between the two ideologies and the date acting as a reminder that everything

including nuclear war and reggae are linked.

The

links between nuclear war and reggae music are endless. There are allusions and direct

references to nuclear war, weaponry, energy and technology in many reggae

songs. Peter Tosh’s song No

Nuclear War is a clear example of the effect that the threat of war has had

on reggae music. The song titles

his grammy award winning album also called No Nuclear War. His message is clear in the first verse

of the song:

“We

don't want no nuclear war

With

nuclear war we won't get far

I

said that We don't want no nuclear war

With

nuclear war we won't get far”[iii]

However while considering that Peter Tosh

was born, raised and lived on the small island nation of Jamaica for almost all

of his life, one has to wonder why Tosh was so concerned with the topic of

nuclear war. There are the obvious

reasons: that nukes and their fallout threatened to kill everybody or even that

the album was made to appeal to western audiences.[iv] Yet reggae music strains to read deeper

into as to what nuclear weapons mean in the prism of jamaican as well as human

history. There are correlations

between the themes of reggae music and the rhetoric of nuclear war. Reggae music understands nuclear war as

simply another vehicle to exploit oppressed societies, often with a racist

mindset, and continue the cycle of promise, expectation and disappointment that

is the plight of oppressed peoples.

Nuclear war is just the next slavery, colonialism or “democracy.” Still there is another view,

resistance, often found in the music.

Reggae

music is built on the themes of rebellion and resistance. The music was born of African roots,

vocal tradition and social commentary.[v] The character of reggae developed even

more along with the course of Jamaican history. The four basic themes of reggae are an embodiment of

Jamaican history: exploitation, racism,

expectation and disappointment, and resistance.v The exploitation of Jamaican people

began with the founding of Jamaica as a slave colony in the 1600s. Slavery went hand in hand with racial

prejudice and racism would prove to be a dominating force through the course of

Jamaican history. After slavery,

former slaves still had no property, freedom or rights. Even today in Jamaica; whites make twice

as much as browns, and thirteen times as much as blacks.v Dark skinned people have been

continually oppressed in Jamaica, since the nations founding.

These

same people have also been filled with promise and expectation that their

fortunes would change only to be disappointed in the long run. First, there was the promise of freedom

from slavery; an act that ended in the same oppression. Then there was the promise of freedom

through democracy, but corrupt governments with white leaders did nothing to

change the status quo. During

these events, reggae served as a medium to express people's feelings and

comment on their environment. When

asked to develop the process by which he creates a song, reggae artist Capleton

captures the essence of Reggae music in his response:

“No, it just come naturally. Capleton is not a youth

that has to puzzle to write a tune, cause

like how

me and you a reason right now, I could

just come

up with a tune. Just from out of the wind and

the breeze. It's just a natural mystic. My tunes

just come natural, and when something out

fi

go down, me always find a tune before it

happen.

A just dem levels. A just Rastafari still, the truth

is the truth, and the only conqueror for

the truth, is

the truth.”[vi]

Reggae musicians simply sing about what

is around them, in the 60s, 70s and 80s, it was the threat of nuclear war.

Twenty

years after the fall of the Berlin Wall, it is hard to understand to what

degree the prospect of nuclear war enveloped the world during the latter half

of the twentieth century. Events

such as the development of nuclear weapons by China and

India, the Cuban Missile Crisis and the installation of medium range ballistic

missiles across Europe all pointed to an inevitable global nuclear war in the

foreseeable future.

A nuclear reality found its way into the core of human culture. Books like Watermelons Not War

were published to help with “parenting in the nuclear age.” The title came complete with with

directions explaining the proper way to talk to your child about nuclear

radiation and cancer or recommendations on how to respond when your child

expresses to you that they do not aspire have children because the possibility

of a gentle death for the next generation is unfathomable.[vii] Scientists at the University of Chicago

constructed a Doomsday clock, intended to count down the minutes until the

catastrophic destruction of the human race based on the current threat of

global nuclear war. Terms like

game theory, acceptable failure rate, minimum deterrence, maximum retaliation

and window of vulnerability were tossed around in reference to national defense

and became household phrases. This

rhetoric conceded that the Cold War was in fact a game being played with people's

lives.[viii]

Similarly,

nuclear war crept its way into Reggae music. There are songs by Bob Marley, Steel Pulse, Jimmy Cliff,

Burning Spear, Mutabaruka, Capleton, Aswad, Herbs, Prince Allah, Ricky Tuffy, Devon Clarke, Luciano, and Soldiers of Jah Army,, that all address

nuclear war in some way.[ix] [x]

[xi]

[xii]

[xiii]

[xiv]

[xv]

[xvi]

[xvii]

[xviii]

[xix]

[xx]

[xxi]

[xxii]

[xxiii]

[xxiv]. There are even album covers dedicated

to nuclear war and the political climate that surrounds the weapons by artists

like Peter Tosh, Herbs and Steel Pulse.

These songs capture feelings of fear,

hopelessness, insignificance, indifference, false security and timelessness all

at the same time. Steel Pulse

describes the era in their song No More Weapons:

“This has got to be the final conflict

Bestowed

upon humanity

So

much for a global coalition

A false sense of security”xi

But the band challenges more than the

realistic nuclear threat in next line of their song. Steel Pulse draws upon the tradition of resistance in reggae

music to confront the underlying rhetorical threat that comes with the mere

possession of nuclear weapons:

“We are just pawns in the scheme of things

No

matter what our race or creed

Survivors

of this holocaust

We international refugees”xi

The rhetorical nuclear threat posed an equal or even larger danger to

the Jamaican people than

nuclear war. The rhetoric of

nuclear war resembled the same discourse that came with slavery, colonialism

and the promise of “democracy. The

same talk that meant more subjugation, exploitation, slavery and

disappointment.

The

main purpose of a nuclear weapon is to suppress dissent. Along with that, nation states that

hold nuclear arms often use their superior position to exploit lesser states.[xxv] The first use of a nuclear bomb aimed

to push Japan into submission during World War II. The destruction of two Japanese cities, Hiroshima and

Nagasaki, was more than enough to both amaze and disgust the world st the same

time. People were in awe of the

weapon's awesome power. Yet, they were

disgusted by its horrible consequences.

The resulting reaction to these attitudes resulted in a nuclear taboo. [xxvi]

Nuclear weapons would never be used again, but even in their non-use, the

weapons projected terrible power.

Ironically, the power behind the traditional non-use of nuclear weapons

served to preserve peace and the spread of nuclear weapons. [xxvii] The successful application of this

power granted “legitimacy to the major powers' monopoly over nuclear weapons.”

(tradition of non use) Nuclear

powers essentially recognized themselves and each other as the only responsible

stewards of nuclear power.[xxviii] The logic behind that reality was

that the danger of a nuclear bomb lies not in the weapon, but in the people

that possess it.[xxix]

A

Multi Atomic Energy Treaty signed between the United States, Canada and Jamaica

in 1984 helps to illustrate this double standard. The treaty was a fulfillment of a request by the Jamaican government to obtain a low

power critical experiment reactor, known as Slowpoke II, for research purposes.[xxx] Although the United States and Canada

were willingly transferring nuclear technology to Jamaica, the oversight and

rights to the material still remained with the United States and Canada. The Supply and Project agreement gave

the United States the right to review, maintain, access, inspect, install and

reclaim the nuclear reactor or any nuclear fuel..[xxxi] It was evident that, in the eyes

of the superpowers, Jamaicans did not have the qualities necessary to

responsibly control nuclear technology.

Nuclear

weapons would also set the standard in determining what level of foreign

intervention a country can expect from a major superpower. The Korean War, Vietnam War, Soviet

invasion of Afghanistan, American invasion of Grenada, Falklands War, Israeli

wars, and war in Iraq are all examples of the type of intervention non-nuclear

states can expect if nuclear states disagree with their policies.[xxxii] Although nuclear weapons were not

used in any of those conflicts, the underlying message was clear: a large

escalation of the conflict will result in destructive force. After all, with the exception of China

(with their no-first use policy), no nuclear state has committed to the non use

of nuclear weapons against nonnuclear states.[xxxiii] This policy of deterrence has

been beneficial to the nuclear states.

No nuclear armed state has faced a foreign invasion or military

intervention of any kind after acquiring nuclear weapons. Once again Steel Pulse touches on the

topic in their song Earth Crisis:

“Superpowers have a plan

Undermining Third World man

Suck their lands of minerals

Creating famine and pestilence

You hear what I say hear what I say”[xxxiv]

Reggae

music also recognizes that the rhetorical nuclear threat has an underlying

racist and classist element to it.

The Multi Atomic Energy Treaty signed between the United States, Canada

and Jamaica already puts on display the double standard between the have and

have nots of the nuclear club. A

close examination of global nuclear policy show even more correlations between

the way a nation is treated in the nuclear era and the dominant race of that

nation. Of the states that either

possess or have come close to possessing nuclear capability, India, Pakistan,

South Africa, North Korea and Iran have all had to deal with the actual

imposition or threat of sanctions for pursuing the development of nuclear

weapons. These countries have a

common trait in that they are all nonwhite nations. On the other hand, the development of nuclear weapons by

Israel went unnoticed and under the silent approval of nuclear armed

states.

The

racist and classist discourse that comes with nuclearism can also be

illustrated by the practice of nuclear testing. When nuclear weapons are used, they have historically been

used on what nuclear states perceive to be an inferior race. This practice began with the intentional

nuclear attack on Japan. However,

while testing, nuclear states sought to detonate bombs in areas far from their

homelands, often in areas with indigenous populations that had no means of

resistance. The United States

tested on the Marshall Islands in the South Pacific, home to indigenous

Micronesians. The Soviet Union

tested in southern Soviet Social Republic, Kazakhstan. The United Kingdom tested on Aboriginal

land in South Australia as well as on Christmas Island in the Pacific. France tested in Algeria. China tested in the autonomous Xinjiang

province, home to ethnic Uighur muslims.

And the recent nuclear tests by India, Pakistan and North Korea have all

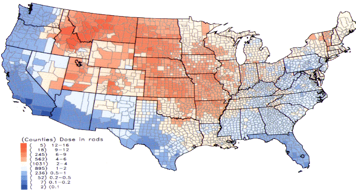

been underground to limit nuclear fallout. The line of reasoning behind testing in an isolated region

was to limit he effects of nuclear fallout on the populations of nuclear armed

states. The limited nuclear tests

in Nevada during 1953 & 1954 resulted in a large area of the United States

being exposed to nuclear fallout.

In the same way, far away areas around the testing sites used by

nuclear states were contaminated by nuclear fallout from testing. The most compelling example of

devastation caused by nuclear testing comes from the Marshall Islands. The test contaminated food supplies,

polluted water, and changed global weather patterns. (the bomb) The Micronesian

people of the Marshall Islands were forced to endure tragedies for a

generation. Miscarriages, cancer

and birth defects became common on these Pacific Islands and the memory of

nuclear testing lingers to this day.

If the Micronesian people from the Marshall Islands suffered such a fate

from nuclear technology, it makes sense that the Jamaican people saw a similar

future written for themselves. Bob

Marley understood the racial implications of war. He suggested a type of

discourse that would vanquish the institution in his song War:

“Until the philosophy which hold one race superior

And another inferior Is finally and permanently discredited

and abandoned -

Everywhere is war - Me say war.

That until there no longer

First class and second class citizens of any nation

Until the colour of a man's skin

Is of no more significance than the colour of his eyes -

Me say war.

That until the basic human rights

Are equally guaranteed to all,

Without regard to race -

Dis a war.

That until that day

The dream of lasting peace,

World citizenship

Rule of international morality

Will remain in but a fleeting illusion to be pursued,

But never attained -

Now everywhere is war

– war.”

Marley understood that war, racism and classism went hand in hand.

In

the beginning, the rhetoric of nuclearism promised a bright future filled with

high expectations for the world.

Nuclear energy was supposed to be clean, affordable and safe. Nuclear research was held to be the

next frontier of science. The

technological advancements of atomic energy were expected to yield great

developments in medicine, astronomy and even food preparation. Nuclear weapons also promised a sense

of security. Mutually Assured Destruction

ensured that no country would commit nuclear suicide and thus prevented nuclear

war. Deterrence ensured the

continuous peace and stability of the globe. Nuclearism did successfully reach many of these goals. Still, reggae artists pondered the cost

of these benefits. Instead of

reaping the rewards of nuclear technology, poorer nations faced disappointment

from the effects of nuclear proliferation. As the third world was struggling with poverty, disease and

hunger; the first world was obsessed with military defense. Peter Tosh's song No Nuclear War expresses the

sentiment:

“We can't take no more

Unemployment

I said the rate is high

So much sick people

I'm sure they

gonna die

So much mad people

Gettin' ready to explode

'Fore

somebody

Come help them carry this load” (tosh youtube)

In Earth Crisis, Steel Pulse agrees:

“They carry the symbol

Of the eagle and the bear

Across the globe

Far east to far west

High tax and cutbacks for military

defense” (earth crisis youtube)

The expectations that nuclear technology promised never materialized

in the developing world and Jamaica.

Once again, Jamaicans were left disappointed.

The

realistic and rhetorical threat of nuclear war was handled by Jamaicans in

typical fashion: resistance through music. Reggae music took the role of to resist the oppression

caused by nuclear weapons and their rhetoric through the entire cold war. Yet despite the fear and oppression,

people would live on and resist.

Reggae legend Bob Marley put it best when he said in his song Redemption

Song:

“Have no

fear for atomic energy,

'Cause

none of them can stop the time.”