Ruby Madden

The Historical and Culture

Aspects of Jamaican Patois

December 1, 2009

The

official language of Jamaica is Jamaican Standard English. The true Jamaican

language that was developed on the island does not have an official name. It is

sometimes called Patois, Creole, Black English Vernacular or ungrammatical

English (Barrett 143-145). The language originally developed as a pidgin. This

is not a native language—it is as second language for everyone who speaks

it. Creole evolves from a pidgin when the pidgin becomes the first speaking

language for all or some of the speakers. It then becomes the language of the

community with children growing up speaking it, seeing the world and increasing

their knowledge in creole. No country uses creole as an official language in

education yet what makes it special is its history (Sebba 2002). The

combination of English and African languages is not unusual. This blend of

language referred to in many different names but in this paper, it will be

referred to as Patois. The language reflects the struggles of slavery and

ancestry from Africa as well as the European colonization and influence

throughout history on the island of Jamaica. The language, despite not being

the official language, has come to represent the people, the culture, history

and struggles of the lives of many Jamaicans. Despite the worldwide use of

English, Patois continues to remain a pivotal element in preserving traditions

and past in Jamaica.

Sometimes

called a bastardization of English, Jamaican Patois is in fact a linguistic

system separate from English with distinguishing factors in its lose structure,

popularity and roots in slavery (McLaren 2009)(Chacon 2001). Patois comes from

French origin meaning “rough speech” and usually carries a negative connotation

(Gladwell 1994). Also called African English, the language of the Jamaican

people began to develop in the 1600’s in Jamaica with the slave trade—the

mix of the European cultures and African created Creole (Gladwell 1994). The

slaves were divided into groups deliberately without a common language to

prevent revolt. The slaves began to learn pidgin in order to communicate with

each other and their masters. The children grew up in this life, learned pidgin

from their parents as their first language and it evolved from pidgin to creole

(Sebba 2002). The African language of Ashanti from West Africa (Niger and

Congo) was also the location where most of the Africans were taken as slaves to

the Americas (Collins 425-462).

Creole is created all over the world as

a natural way that languages evolve. They are not primitive, but reveal the

state of mind of the people in society (Collins 425-462). During slavery and

plantation days as well as after emancipation, there were many variations of

Patois being spoken (Kuppens 43-55). These languages show what develops when

widely different backgrounds are forced together and have to communicate.

To

provide a little background on Jamaica as a country, it was discovered by

Christopher Columbus in 1492 and then taken over by Britain in 1655 where it

was a plantation economy of sugar, cocoa and coffee. The total area of the

island is 10,991 sq. km. with 2,825,928 people 91.2% of which are black, 6.2%

are mixed and 2.6% are other or unknown. With a life expectancy of 73.53 years

and 2.25 children born per woman the country is relatively healthy and well

established. The literacy rate is 87.9% and part of the reason for this number

is the conflict between Jamaican Standard English and Patois. It is a

commonwealth of Britain and has a constitutional parliamentary democracy. The

GDP per capita (the average salary a person lives on in a year) is $8,600 and

14.8% of the population are below the poverty line ("Jamaica," 2009).

The

official language of Jamaica is Jamaican Standard English. However, most of the

population speaks a different language—that of Patois. English is

understood (if not spoken) all over the island but understanding Patois as a

visitor is much more challenging. There is a debate about making Patois another

national language. With this debate comes the conflict of which language is

better with Afro-Jamaican Patois as one extreme and standard English as another

(Adams 1-65). Patois has been described as ungrammatical spoken by the

uneducated (Barrett 143-145). Jamaican Standard English is the language of

those who govern and come from privilege and has become an indicator of social

class while Jamaican Patois is the first language of many and later they may

learn English as a language. English is the language of education, religion

(institutional not ethnic), commerce and government while Patois is the

language in which stories are told and passed down orally and many songs and

literature written in (Justus 39-51).

Children

born in rural parts of the country learn Patois from their parents usually in a

monolingual home. At age six, they go to school where they are taught

exclusively in English. Starting at age 10, speaking in Jamaican Standard

English is a mark of social class, achievement and potential. There is

universal education through primary school for all Jamaicans. Those who

continue in school, increase their proficiency in English while those who stop

school will most likely go back to speaking Patois and use that for the rest of

their life (Snider 2 December 2009). Speakers of Patois use it because their

parents did and sometimes they are unable to advance in their education so they

continue speaking the language of their society. There are standards in society

of when and where each language is used; children learn this very quickly in

order to prevent social embarrassment. English is used for business and work

(including international agreements and affairs) while Patois is used for at

home and social interactions (Chacon 2001). All Jamaicans generally understand

Patois, it illustrates the condition of Jamaican people, distinguishes the

country from Europe and expresses the beliefs of the people: identity, race and

protest. An example of social rules of when to use English and when to

communicate in Patois is illustrated here with Mary (the mother) and her

daughter Charlotte:

Mary: Yes mam. dem pikni diffarant dees deys

yunno. (yes, madam .. these children are

different

these days you know).

Researcher: Different?

Mary: Dem baan big ... dem grow faas faas ...

de world change up ... I glad (them born

big...

them grow fast fast. the world change up ... I am glad) ... glad Chatti like

she

iz

. . Chatti tel Joyce what hu lern a skool tide. (Charlotte like she is. .

Charlotte

tell

Joyce what you learn at school today).

Charlotte: (rather slowly and enunciating

every syllable) I learn bout Marcus Garvey,

our

national hero.

Barbara and Fay: (anxious to join in the

exchange) Yes . . yes, we learn bout Garvey.

Mary: What I tel yu ...

(Justus 39-51).

Jamaican school children

Those

who feel it will be costly for them to associate with those who are less

educated and fortunate than them, will be less likely to maintain social

standard (of speaking Patois in informal contexts). They also are very

concerned with the “whiteness” of their speech. Jamaicans who hope to elevate

themselves in society but have no access to wealth of social class sometimes

deny the ability to speak and understand Patois (Justus 39-51). The two times

when it is acceptable to use Patois is for songs/folklore and songs (either

traditional or modern).

All

Creole has similar grammatical structure, vocabulary, sound and syntax that

come from roots in African language (Gladwell 1994). The use of only one tense

reflects the Niger-Congo roots of languages where they do not have the aspect

of time either (hence no past or future tense)(McLaren 97-110). The structure

of Patois has no standard method for writing the language (Adams 1-65). Writing

the actual language of Patois becomes very confusing because of the variations

in spelling. Often Jamaican children are taught to spell and write how they

speak and this is one of the reasons they struggle in writing English (Problem

with Patois is in Writing It 2004). As Jamaican is spelled phonetically and

English words are spelled with a standard, there is a huge contrast when they

are put together (Adams 1-65).

Words can also vary in meaning and spelling from different areas but the

more people begin to get used to writing Patois, there will be more regulation

on subjects of grammar and verbs (Chacon 2001).

|

SOUND |

GRAMMAR |

VOCABULARY |

|

Deze—these Bes’—best Helt’—health |

Dem walk—they walked Him belly—his belly Mi kick—I kicked |

Fi—to Pan—for T’ief—to steal |

Some

of the ways that Patois is written include consonants switching sometimes (film

to flim), adding another consonant (fishing turns to fishnin) or letters

replace eachother (handle to hanggl). Letters are also dropped in combination

with “s” (skin turns to ‘kin). There is no “TH” sound in the language so “thick”

becomes “tick”. Plurals are also implied or understood and the singular form of

the noun is both plural and singular (one foot, two feet would be one foot, two

foot). The suffix for plurals of “s” does not exist and when a plural is

needed, “dem” is used (the girls are coming is said as di gyal-dem a come).

There is usually no use of adverbs by adding “ly”, instead it is just the same

word (isn’t the child quick? Would be said as “di pikny quick, eeh?). The

pronouns are also set up differently than most other romance languages, not

just English (Adams 1-65).

|

|

SINGULAR |

PLURAL |

|

1st |

Mi, I (me, I) |

Wi (we/us) |

|

2nd |

Yu (you) |

Yu, uno (you, you all) |

|

3rd |

Im (he/she, her/him, it

animate) Shi (she/her) Har (her) I’, it, hit (it,

inanimate) |

Dem (they/them) |

Dread

talk also called “Rasta talk”, “soul language” or “ghetto language” is a

vocabulary that was created to meet needs of Rastas in society. With

Rastafarianism spreading to different countries, innovation, adaptation, translation

and integration with other languages is creating change. It has spread through

Jamaican culture and around the world. Through music, the language and

philosophy of the Rastafari have been spread globally. In the Rasta culture,

oral language is used to transfer “doctrinal and life matters”. The powerful

rhymes and rhythms of music have passed the message of the Rastafari (Pollard,

and Davis 59-73). The use of “I and I” has had an impact on Jamaican language

as well as literature written telling stories or events (McLaren 97-110). It

replaces "him," she," "we," "you," and

"me” and uses “I and I” to recognize that the community of the Rastafari is

all around and then gives praise and acknowledgement to the Almighty. The

Rastafari believe that the sounds of words have power so they have altered

words from English that mean the same thing, but are different. “Understand”

was changed to “overstand” because they do not comprehend the “under” part of

the word. “Appreciate” turned to “apprecilove” because the “ate” part sounds

like “hate” and therefore this sounds more positive. The “library” was changed

to “truebrary” to respect the knowledge gained and stored there (Lee 1998).

Other words from the Rastafari culture are:

|

Bredren |

Male Rasta companions |

|

Battybwoy |

A gay person |

|

Jah |

God, used sometimes to

give praise to all of the above: Jah Ras Tafari, Haille Selassie

(personification of the Almighty), King of Kings, Lord of Lords, conquering

Lion of Judah |

|

Mampi |

Fat or overweight |

|

Pakny |

A child |

|

Rude Boy |

a criminal, a hard hearted

person, a tough guy |

(Jamaican Patios Dictionary

2009)

As

mentioned earlier, the language of Patois socially acceptable to be used for

specific things: stories, folklore, literature and song lyrics. The songs can

be either traditional or modern and often need to the use of Patois to create

the meaning; if translated, the same literary techniques and devices may not

convey. Lyrics can have double entendres and knowledge for local culture is

needed to understand the meaning. Also themes in social democracy, conditions

of society and the trials and tribulations of the black people are all

expressed through these areas.

With lyrics from various artists using the language of the people of

Jamaica, an example is Bob Marley in the song Rainbow Country (Justus 1978).

Hey Mr. Music

Ya sure sound good to me

I can't refuse it

What got to be, got to be

Feel like dancing

Dance cause we are free

I got my home

In the promise land

But I feel at home

Can you overstand

Said the road is rocky

sure feels good to me

and if your lucky

together we'd always be

Are you really rideing?

the sun is a risin'

the sign is a risin'

Moon is rising

Another

example is the poet Linton Kwesi Johnson’s words in Sonny’s Lettah (Sebba

2002).

I hope that when these few lines reach you

they may

Find you in the best of health

I doun know how to tell ya dis

For I did mek a solemn promise

To tek care a lickle Jim

An try mi bes fi look out fi him

Mama, I really did try mi bes

But none a di less

Sorry fi tell ya seh, poor lickle Jim get

arres

It was de miggle a di rush hour

Hevrybody jus a hustle and a bustle

To go home fi dem evenin shower

Mi an Jim stan up waitin pon a bus

Not causin no fuss

When all of a sudden a police van pull up

Out jump tree policemen

De whole a dem carryin baton

Dem walk straight up to me and Jim

One a dem hold on to Jim

Seh dem tekin him in

Jim tell him fi leggo a him

For him nah do nutt'n

And 'im nah t'ief, not even a but'n

Jim start to wriggle

De police start to giggle

Mama, mek I tell you wa dem do to Jim?

Mek I tell you wa dem do to 'im?

Dem thump him him in him belly and it turn to

jelly

Dem lick 'im pon 'im back and 'im rib get pop

Dem thump him pon him head but it tough like

lead

Dem kick 'im in 'im seed and it started to

bleed

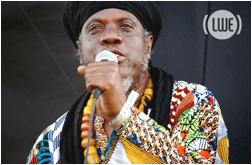

Another

aspect of the language used in society is story telling and literature. Poetry

also has become a large outlet for the use of Patois that is accepted in

society. Jamaican poets are often called dub poets. They use Africanized

English (Patois) to add legitimacy to the “national language” of Jamaica. Poets

such as Michael Smith and Mutabaruka use Patois as their language for their

works.

nah tek nuh more lie

nah sidung [sit down] an cry

nah ask yuh de reasons why

white supremcecy mus end. –Mutabaruka

Also, the poet Kamau

Brathwaite who writes all over the Caribbean uses Creole as the language of his

poems. Connecting with the people as well as the culture and country.

Dear mama

I writin yu dis letter/wha

guess what! pun a computer o/kay?

like I jine de mercantilists!

well not quite!

I mean de same way dem tief/in gun

power from sheena & taken we blues &

gone

(McLaren 97-110)

There

has been a debate among the people of Jamaica as well as the rest of the world

about the issue of bilingualism in Jamaica. Most of the population is in fact

bilingual with nearly 80% of the island speaking both English and Jamaican.

From a survey, many people feel that parliament in Jamaica should deliver their

speeches in Patois to better communicate with their constituents. Those who

understand English will understand Patois but not the other way around. English

is now the official language of Jamaica; however, 69% of the people feel that

Patois should be made an official language as well (Francis 2005).

Bilingual

schools are another issue being discussed. Most of the children growing up

learning to speak Patois and only when the enter school do they begin to learn

English. Most schools do not allow speaking of Patois in order to force the

children to learn English fast. It is very valuable to be able to speak both

languages however some do not finish school. This then continues the pattern of

children growing up learning Patois because that is what their parents speak

and then later learning English as a second language (Francis 2005). Despite

the similarity in race, bilingual projects have also had scorn and criticism

due to it being expensive and the social feelings about Patois as a language.

It is sometimes called “degenerate English” with “raw mispronunciation”. There

is another social aspect to this as well; the educated upper class, tend to

have lighter skin and speak English. The majority of Jamaicans struggle

economically with low wages and use Patois daily, listen to music using Patois,

identify with the words and have darker skin. The divide between the two

languages and races is about culture, linguistics, economic standing and skin

color (Cooper 16-20).

The

mix of language that was created is unique to Jamaica—with its African

heritage and European Influence, the Creole of Jamaica reflects the culture

created on one island throughout its history. The language represents the

people of Jamaica, their historical struggle for equality and the life style

and culture of people.

WORKS CITED:

1.

Adams, Emilie L.

Understanding Jamaican Patois, Jamaican Grammar. Kingston, Jamaica: Kingston

Publishers Limited, 1991.

2.

Barrett, Leonard

E. The Rastafarians. Boston MA: Beacon Press, 1988. 143-145. Print.

3.

Chacon, Richard.

"New Technology Aiding Old Tongue in Jamaica." Boston Globe 28 June

2001, Print.

4.

Collins,

Michael. "What We Mean When We Say 'Creole': An Interview with Salikoko S.

Mufwene." Project Muse: Scholarly Journals Online (2003): 425-462. Web. 1

Dec 2009.

5.

Cooper, Kenneth

J. "Parts of Speech." Crisis (2009): 16-20. Web. 1 Dec 2009.

6.

Francis,

Petrina. "Majority Favour Patois as an Official Language of Jamaica."

Gleaner 2 November 2005, Print.

7.

Gladwell,

Malcolm. "The Creole Creation." Washington Post 15 May 1994,

SundayPrint.

8.

Justus, Joyce

Bennett. "Language and National Integration: The Jamaican Case."

Ethnology 17.1 (1978): 39-51. Web. 1 Dec 2009. <http://www.jstor.org/stable/3773278

>.

9.

Kuppens, An H.

"Authenticating Subcultural Identities: African American and Jamaican

English in Niche Media." Journal of Communication Inquiry. (2008): 43-55.

Print.

10.

Lee, Yishane.

"A Key to "Overstanding" Jamaican Patois." Japan Times 10

September 1998, Print.

11.

McLaren, Joseph.

"African Diaspora Vernacular Traditions and the Dilemma of Identity."

Research in African Literatures 40.1 (2009): 97-110. Web. 1 Dec 2009.

12.

Pollard, Velma,

and Samuel Fure Davis. "Imported Topics, Foreign Vocabularies: Dread Talk,

the Cuban Connection." Small Axe 19 17.1 (2006): 59-73. Web. 1 Dec 2009.

13.

Sebba, Mark.

(2002). Creole English and Black English. Retrieved from http://www.ling.lancs.ac.uk/staff/mark/resource/creole.htm

14.

Snider, Alfred. Class lecture. 2 December 2009.

15.

"Jamaican

Patois Dictionary." Rhetoric of Reggae. 14 October 2009. Web. 1 Dec 2009.

<http://rhetoricofreggaer.blogspot.com/2009/10/jamaican-patois-dictionary.html

>.

16.

"Problem

with Patois is in Writing It." Gleaner 17 November 2004, Print.

17.

(2009, November

11). Jamaica. Retrieved from CIA World Factbook. https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/jm.html