Economics 172

Spring 2005

Homework 3

Due Friday Feb 11

Chapter 3 Review Questions and Problems

3.1

3.5

3.7

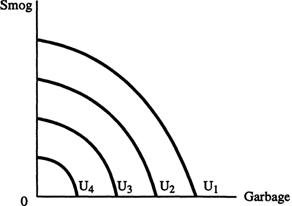

Two bads have downward sloping shaped indifference curves, concave to the origin. Why? Suppose you consume a lot of smog, but not much garbage. Someone offers to take some of your smog away. You are very happy and will willingly part with some smog, which makes you better off. But now you have to consume more garbage to make you worse off. You’ll take a lot of garbage in exchange for a little less smog, so the indiference curve is relatively flat near the smog axis.

The other, and more important difference, is that utility increases as you get closer to the origin.

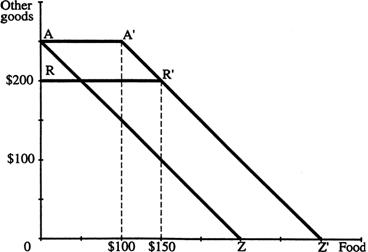

3.16 You start with budget line AZ. The original food stamp program required you to pay $50 to get $150 in stamps. If your original income was $250, then you could only buy $200 of the composite good (point R). But you get $150 of food (point R’). The new budget line is RR’Z’. The new budget line from R’ to Z’ is parallel to AZ because the relative price of food has not changed.

The outright gift of $100 in food stamps puts you on budget line AA’Z’. for someone who was consuming more than $150 worth of food, the two programs would make no difference. For someone who consumes less than $150 of food, the outright gift would make them better off than the program that existed pre 1979 since they could consume on an indifference curve that was tangent somewhere along A’R’ whereas with the pre1979 law they would consume at R’.

3.18 Diminishing MRS says that as you have proportionately more of one good, the less you value an additional unit of the good relative to the other good. If a family has a boy first, then the relative value to the family of a girl increases while the relative value of a boy decreases. Similarly, if the family had a girl first, then the relative value of another girl falls while the relative value of a boy increases.

3.22 If the government allows Sam to deduct her contributuion to Oscar from her income before the tax rate is applied, then the “price” of giving to Oscar is reduced so the budget line is flatter and now has a slope of 0.6 instead of 1.0. If Sam earned $100 her income taxes would be $40 and her after tax income would be $60. If she gave Oscar $10, her after tax, after transfer income would be $50.

Now she can give $16.67 to Oscar and have the same after tax, after transfer income as before. She deducts the $16.67 from her $100 income and pays taxes on $83.37. 40% of $83.33 is $33.33 so she has $50 left, just as before.

Another way to look at it is that it only takes Sam a

reduction of $6 of her own after tax income to give Oscar $10, since the

government is effectively giving Oscar $4 for every $6 Sam gives him. This is why charities like the tax

deductibility of charitable giving on the

3.26

When you put 50 cents into a newspaper vending machine, the first newspaper gives you a lot of marginal utility. The second newspaper you take gives you almost zero, or exactly zero, so those vending machines make it easy to be able to take more than 1, but most people don’t. If you could do that from a soda vending machine, many people would because a second soda gives you a great deal of marginal utility (although less than the first soda).

1. During World War

II the

Any consumer who would have consumed more than 10 gallons of gas is worse off.

2. Michelle doesn’t

care where she lives, but she does care about what she eats. She spends all her income on restaurant meals

at either American or French restaurants.

Her firm offers to transfer her from her current

The drawing is not perfect (I’m not great at freehand Excel graphing) but here’s the logic. Start out at the budget line that goes from 20 French meals per month to 40 American meals. There’s an indifference curve tangent at point A.

Her firm offers to transfer her from her current

So even though she could consume the same quantities of American and French meals, she won’t because relative prices are different. She’ll be better off by buying fewer American meals and more French meals.

Here’s a question:

Suppose French meals are more expensive in