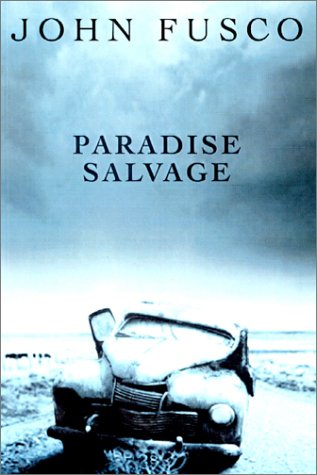

Review of John Fusco's Paradise Salvage

Waterbury (CT) Republican-American

January 13, 2002

by Alfred Rosa

What

a great read John Fusco provides in his debut novel set in Saukiwog Mills,

a fictionalized Waterbury, Connecticut. Fusco grew up in Waterbury

and still has relatives and friends in Town Plot. He pays tribute

to his roots, but it is, despite uproariously funny passages, a somewhat

mournful celebration.

What

a great read John Fusco provides in his debut novel set in Saukiwog Mills,

a fictionalized Waterbury, Connecticut. Fusco grew up in Waterbury

and still has relatives and friends in Town Plot. He pays tribute

to his roots, but it is, despite uproariously funny passages, a somewhat

mournful celebration.

Once proud and strong, Waterbury’s City Hall again reels from charges

of political corruption. So what could be more timely than the story

twelve-year-old Nunzio Paradiso tells as he is wrenched from his innocence

and thrust into the world of experience? For Nunzio and us, the novel

is both a love-song to his people and a horrible look into the abyss, a

look at Waterbury as she used to be and as she has sadly become.

In the tradition of Dickens, Twain, and Salinger, Fusco’s main character

struggles on many fronts, but he is wise and big-hearted and gives a good

account of himself. Fusco’s control as a novelist is amazing.

He immediately makes us at home in the Paradiso family, orchestrates a

suspenseful and believable plot, unfurls the ethnic tapestry of the city,

and provides memorable characters who are rich in language. Paradise

Salvage is a carefully researched and generous work, and the best literary

treatment that Waterbury has yet received.

Not since Pietro DiDonato’s Christ in Concrete, the classic masterpiece

of Italian American literature, have we been blessed with such a realistic

portrait of life in Little Italy. Unlike that 1939 masterpiece which

focuses on the poor immigrant class, Fusco delivers, through Nunzio’s

sharp eyes and quick tongue, the essence of the Italian American middle-class

experience in the latter part of the last century.

Against

the rich backdrop of the city’s ethnic diversity—Italians, Irish, Lithuanians,

Scots, Germans, Poles, Portuguese, Puerto Ricans, African Americans, Cambodians,

French Canadians--Fusco’s narrator struggles to understand the reason why

a man has been murdered. Nunzio Paradiso, whose family owns Paradise

Salvage, spends the last summer of his childhood working in the junkyard.

There he finds the body of a brutally murdered man in the trunk of a wrecked

’73 Pontiac Bonneville, but before he can convince his brother and father

of his discovery the car is fed to the Green Monster, the junkyard’s crusher.

Against

the rich backdrop of the city’s ethnic diversity—Italians, Irish, Lithuanians,

Scots, Germans, Poles, Portuguese, Puerto Ricans, African Americans, Cambodians,

French Canadians--Fusco’s narrator struggles to understand the reason why

a man has been murdered. Nunzio Paradiso, whose family owns Paradise

Salvage, spends the last summer of his childhood working in the junkyard.

There he finds the body of a brutally murdered man in the trunk of a wrecked

’73 Pontiac Bonneville, but before he can convince his brother and father

of his discovery the car is fed to the Green Monster, the junkyard’s crusher.

After winning his brother Danny Boy to his side, the two set out to

solve the mystery of the murder less as a matter of justice than as a way

of protecting the family from the killers who might try to silence them.

The effort quickly brings them to Goomba Archangelo Volpe, one of the most

skillfully drawn and vibrant characters in contemporary fiction.

Angelo is nasty and crude, a hardened character who knows his way around

the city’s underworld. As an ex-cop he has been over this ground

before, and he has paid for his miscalculations by having been turned into

a miserable, misanthropic quadriplegic. It is Angelo, finally, who

leads Nunzio and Danny Boy into the inner workings of a rat’s nest of corruption

involving, developers, construction companies, city hall, the mob, and

kickbacks. Fusco will soon produce and direct the film version of

Paradise Salvage and so fascinating a character is Angelo that the actor

lucky enough to play him on the screen could find himself an instant success.

What is so clever on Fusco’s part is the way he wraps Nunzio’s coming

of age around the story of why the man in the trunk has been murdered.

Readers will recognize the Italian deli on the hill, Holy Land USA near

the old Scovill Mill, Route 8, green slime in the Naugatuck River, the

Big Clock where this newspaper is published, Soldier’s Horse on the Green,

sleazy strip joints, chop shops, seedy apartment buildings, and perhaps

even the smell of almonds and the taste of the crunchy sfogliatelle

in Fusco’s warm tribute to one of my childhood shrines, Ortone’s Pastry

shop.

What grabs our attention more than the landmarks, though, are the accurate

and telling details of life in the Little Italian Boot, the close-knit

Pontelandofesi, the Calabrese, the food--baccala, soprasatta, braccioli,

biscotti, fusilli, and calamari. It’s the comparatico,

the system of godmothers and godfathers (Nunzio has three goombas but none

who really knows him) that’s realistic and endearing to all of who grew

up in this world. And it’s the malocchio revisited for us,

as Nunzio learns the secrets of his heritage from tribal elders.

Added to the novel’s great sense of Italianita is the love of story

telling and the Scottish burr of Nunzio’s mother Nancy, once an outsider

but now a validated and honored member of the Italian clan.

Life in Saukiwog is filled with vividly realized characters whose language

is so authentic and natural you become a part of the conversation.

We have the harmless dialogue of the youngsters that turns raw and lusty

in the mouth of Nunzio’s older brother Danny Boy and stern in the contemptuous

snarling putdowns of Big Dan, their father. And, by turns, we have

black slang, Spanish American dialect, and the clipped wiseguy talk of

the toughs who people the seamier side of Nunzio’s story. There’s

tabooed language here, quick and dirty retorts, taunts, and verbal swings

and counter-punches. As a screenwriter, Fusco knows that language

is character, that “You are what you say.”

Fusco

also wisely allows Nunzio to tell his story, to show us his world through

his own eyes. His is a world of cars, cars that are full of life

and cars that are entombed, and the images and figure speech that come

naturally to him are those of the world as he sees and knows it.

Hence, his fascination with automobiles as the place in which we live and

die, think and dream, eat and sleep, find and lose, love and deceive, spy

and plot, and identify and reinvent ourselves is quite brilliant.

Fusco

also wisely allows Nunzio to tell his story, to show us his world through

his own eyes. His is a world of cars, cars that are full of life

and cars that are entombed, and the images and figure speech that come

naturally to him are those of the world as he sees and knows it.

Hence, his fascination with automobiles as the place in which we live and

die, think and dream, eat and sleep, find and lose, love and deceive, spy

and plot, and identify and reinvent ourselves is quite brilliant.

Fusco does so many things so well in this novel. What’s refreshing

and innovative for me, impressive really, is his ability to weave the love

of cose Italiano, of things Italian, into his main character’s struggles

in dealing with the adult world and the threat he faces. In Nunzio’s

move from innocence to experience, Fusco particularizes the larger story

of the efforts of Italian Americans to hang onto the best of la via

vecchia, or the old way, while negotiating la via nuova, the

new way of life. In that regard he also intimates the struggles of

all ethnic groups to hang on to what’s genuine, to assimilate, and to fight

off the evil that threatens them. It is, after all, the great story

of America itself.

Alfred Rosa, whose grandparents lived on Washington Avenue, is a

native of Naugatuck. He is Professor of English at the University

of Vermont in Burlington, Vermont.

Return to English 187: Italian American Literature

Against

the rich backdrop of the city’s ethnic diversity—Italians, Irish, Lithuanians,

Scots, Germans, Poles, Portuguese, Puerto Ricans, African Americans, Cambodians,

French Canadians--Fusco’s narrator struggles to understand the reason why

a man has been murdered. Nunzio Paradiso, whose family owns Paradise

Salvage, spends the last summer of his childhood working in the junkyard.

There he finds the body of a brutally murdered man in the trunk of a wrecked

’73 Pontiac Bonneville, but before he can convince his brother and father

of his discovery the car is fed to the Green Monster, the junkyard’s crusher.

Against

the rich backdrop of the city’s ethnic diversity—Italians, Irish, Lithuanians,

Scots, Germans, Poles, Portuguese, Puerto Ricans, African Americans, Cambodians,

French Canadians--Fusco’s narrator struggles to understand the reason why

a man has been murdered. Nunzio Paradiso, whose family owns Paradise

Salvage, spends the last summer of his childhood working in the junkyard.

There he finds the body of a brutally murdered man in the trunk of a wrecked

’73 Pontiac Bonneville, but before he can convince his brother and father

of his discovery the car is fed to the Green Monster, the junkyard’s crusher.

What

a great read John Fusco provides in his debut novel set in Saukiwog Mills,

a fictionalized Waterbury, Connecticut. Fusco grew up in Waterbury

and still has relatives and friends in Town Plot. He pays tribute

to his roots, but it is, despite uproariously funny passages, a somewhat

mournful celebration.

What

a great read John Fusco provides in his debut novel set in Saukiwog Mills,

a fictionalized Waterbury, Connecticut. Fusco grew up in Waterbury

and still has relatives and friends in Town Plot. He pays tribute

to his roots, but it is, despite uproariously funny passages, a somewhat

mournful celebration.

Fusco

also wisely allows Nunzio to tell his story, to show us his world through

his own eyes. His is a world of cars, cars that are full of life

and cars that are entombed, and the images and figure speech that come

naturally to him are those of the world as he sees and knows it.

Hence, his fascination with automobiles as the place in which we live and

die, think and dream, eat and sleep, find and lose, love and deceive, spy

and plot, and identify and reinvent ourselves is quite brilliant.

Fusco

also wisely allows Nunzio to tell his story, to show us his world through

his own eyes. His is a world of cars, cars that are full of life

and cars that are entombed, and the images and figure speech that come

naturally to him are those of the world as he sees and knows it.

Hence, his fascination with automobiles as the place in which we live and

die, think and dream, eat and sleep, find and lose, love and deceive, spy

and plot, and identify and reinvent ourselves is quite brilliant.