|

||

| uvm a - z | directory | search |

|

DEPARTMENTS Alumni

Connection LINKS

|

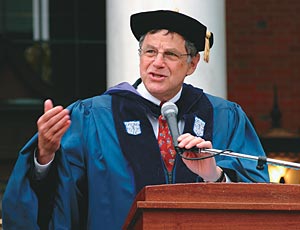

Teaching

Feeling

2005 Kidder faculty Award

by Kevin Foley

photo by Bill DiLillo

Huck

Gutman skitters across the lecture hall stage reciting poetry, his hands

whorling the still classroom air, his expressive voice, a marriage of

literature and Long Island, rising and falling as the lines surge and

ebb. The English professor is lost in the moment, or at least looks that

way; he drops to his knees to nail a dramatic phrase. Then he stills for

a long beat: “What is this guy talking about, anyway?”

The question, both in its irreverent delivery and cutting substance, is

pure Gutman. What are poets saying to us? Why should we care? These questions

are the objects of his expertise, passion, and buoyant curiosity. Poems

start the conversations we need, but so rarely have, he says. They talk

about sex, death, love, beauty, failure, redemption… important things

barely discussed, even with loved ones. But everything starts with listening,

literally and figuratively, so a key tool in Gutman's teaching repertoire

is reading aloud.

“I had never heard a more perfect speaker of poetry than Huck - he

knew exactly when to add emphasis, knew the poems so closely it was if

he had written them,” recalls Kurt Johnson G'03. Johnson, who currently

teaches English in rural Japan, says one recitation four years ago still

echoes in his mind. “We were reading 'Asphodel, That Greeny Flower'

by William Carlos Williams, and he read it with such tenderness and heart-felt

longing that he started to cry, and I almost did too. I think that struck

a lot of people - his passion for the poetry. And it certainly rubs off.”

Gutman's infectious enthusiasm earned him this year's George V. Kidder

Distinguished Faculty Award from alumni, the University's most prestigious

award for teaching. (In a rare double-dip, Gutman won also won the Kroepsch-Maurice

Teaching Award this year.) Both awards testify to the resonance of a vocation

he chose early.

Growing up as the bookish son of refugees who fled the Nazis, young Stanley

Gutman, made a momentous decision: He would become a college professor

of English. He would spend his days and life reading and talking about

books. “I marvel at it…” he recalls. “The idea that

anybody would let a 16-year-old kid decide what he is going to do with

his life is staggering, but that's what I did: I let the 16-year-old-kid

decide for me, that kid who was me, and I have liked it and loved it ever

since.”

He went on to college at Hamilton (where the future literature prof acquired

his literary nickname), graduate school at Duke, and in 1971 arrived in

Burlington, where he has taught novels and poetry ever since. Striving

to do that well has taken him in directions likely and unexpected: He

has negotiated a truce with PowerPoint (to project poems, paintings and

music for his lectures), become an impresario of sorts (bringing pianists

to campus to play difficult modern music that complements his classes),

and even became a political columnist for several major newspapers in

Asia (a gig that started after he completed a Fulbright teaching fellowship

in India).

The connecting thread is a sensibility suffused with poetry, art, and

politics. Over the course of a conversation, Gutman quotes effortlessly

and without pretension from Walt Whitman, Wallace Stevens, T.S. Eliot,

Wordsworth, and Emerson. The core of his teaching, he says, is helping

students similarly open themselves up to poetry.

“I think my job in the classroom is not to parse lines, it is to

have people approach a poem not as if it was a crossword puzzle for the

verbally bright but to hear what a poet is saying,” Gutman says.

“In order to do that you have to pay great attention to the lines.”

His voice rises. “I hate it when students come up and say, 'errrrm,

this is what I feel about a poem' without paying attention to the lines.”

Feeling is more than emotion. It's an ever-shifting complex, a blend of

thought and emotion and situation that poetry is well suited to untangling.

Gutman loves ideas, and has a strong philosophical bent, but chose to

study literature in part because it tackles how ideas function in the

world, in the grumbling belly. It's less rational, maybe more real. “We

don't just think our way through the world, we feel our way through the

world,” he says.

Nobody goes to college wanting to learn how to feel, he says, but it happens

and it's important. By way of explaining, Gutman quotes some favorite

lines from Walt Whitman's “Song of Myself.”

“He says, 'It is you talking just as much as myself…. I act

as the tongue of you, it was tied in your mouth…. in mine it begins

to be loosened.' He's saying if we read poems attentively, we hear ourselves

speaking. … It's a wonderful way of looking at poems. They tell us

about ourselves, they help us see things that we think and we feel but

we don't necessarily know we think and we feel until they're put into

words.”

In that, poets are akin to teachers. Whether darting lecturers or confidants

or leaders of lively discussions or some mixture of all three, Gutman

believes great teachers have one commonality in their diversity: they

pull students into their passions. A Wordsworth line he cherishes elaborates:

What we have loved, others will love, and we will teach them how.

“That's the very heart of teaching… it's trying to urge students

to take seriously what we care so much about, and show them how they might

approach it so it is as rich for them as it is for us,” Gutman says.

The professor tries to tug students into his passions with lively readings,

by spending hours before classes gathering historic visuals or burning

homebrew CDs of music that he accompanies with six- or 10-page “letters”

in which he strives to make sense of the sounds. (After more than 30 years,

the professor is still trying new tricks, still changing, especially as

he brings music, art, and architecture into courses more than ever before.)

The results of all this, always, are a mystery. Maybe nothing - or maybe

a former student writes seven years after a class Gutman thought tanked

and says it changed his life.

“What happens after they enter into it, after they look around and

see and hear what is there in the poem, after they hear what the poem

says to them, what they do with it, I can't predict,” he says.

John Pucci '75 probably wouldn't say that Huck Gutman changed his life,

but the professor was important for him at a vulnerable time.

The details of the novels he and Gutman probed together have faded now,

thirty years later, but the details were never the important things for

Pucci, now a litigator in Northampton, Mass. What the professor did for

him, more than elucidate tropes or help track the arc of a character's

growth, was make the working-class kid comfortable. Other professors also

knew their stuff and were passionate about it; Gutman was the guy who

seemed like he really wanted to talk with you.

“He was nurturing,” Pucci says. “He was caring, welcoming.

He made me feel comfortable entering a world. I did not come from a sophisticated,

intellectual background. He was a guide who opened doors.”