|

||

| uvm a - z | directory | search |

|

DEPARTMENTS Alumni

Connection LINKS

|

The

Bronx to Burlington

Building diversity has never been easy at UVM, but a thriving partnership

with a New York City high school has spurred major progress.

by Rachel Morton

photography by Shayne Lynn '93

They

have been observed, remarked upon, worried about, interviewed, photographed,

held up as role models, extolled, and finally, on May 22, they were celebrated

as University of Vermont graduates, Class of 2005. Like every other student

at UVM, they came to the University to get an education, and they probably

just wanted to be ordinary college students. But unlike the rest of the

student body, this circle of young people from the Bronx often had a very

public platform for their educational journey.

It all

began four years ago, when they arrived at UVM as ambassadors of a kind

from New York City's most multiethnic and least affluent borough. The

Urban Partnership Program, which was designed to expand the options for

students at Christopher Columbus High School in the Bronx and to increase

the diversity of the student body at UVM, had gotten off to a strong start,

enrolling 13 students in 2001.

From the start, there were cultural differences, race differences, class

differences, and even some notable weather differences, the students say.

Bronx, New York, is about as different from Burlington, Vermont, as a

place could be. Nearly 75 percent of the more than one million people

residing in the Bronx are African-American or Hispanic. Burlington, by

contrast, is 92.8 percent white, and with a population of 38,899 Vermont's

largest city isn't quite the Big Apple.

But to the Columbus students who first arrived with their families to

see the campus in 2001, UVM, in spite of its extreme difference, offered

a wonderful opportunity for a first-rate education. It also offered them

a new perspective on themselves and the world.

Their presence on campus turned out to offer the exact same thing to the

University.

Director of Admissions Don Honeman, in talking about the notable successes

of the Urban Partnership Program, points to the numbers: In the fall of

2000, the minority undergraduate population of UVM stood at about 4.6

percent. Today it's up to 6.6 percent. Sixty-two Columbus graduates were

enrolled at UVM during the 2004-2005 academic year, and 12 more are set

to join UVM's Class of 2009 in the fall. What's more, the Columbus students

are far from being the sole difference - 179 ALANA students will enroll

in August, an 11 percent jump from last year's number. “We're on

a good trajectory,” Honeman says. But the real measure of success

is in the extraordinary kids, he notes, and the incredible gifts they

bring to the campus.

A

Sense of Potential

A

Sense of Potential

When Leniece Flowers first visited campus, as a senior from Christopher

Columbus High School, she liked what she saw. “I came here and fell

in love,” she says. “The mountains, the environment.”

Her mother, Lynnette Flowers, visited and liked the feeling of the place,

too. “It wasn't New York and I was grateful for that. There was a

slower pace, a community feeling. I was like, 'Great!' Plus Leniece has

always been resourceful. I told her, 'Hold your head up. People will recognize

you. You can't speak for the race.'”

Her father, Kelvin Flowers, concurred: “I felt she'd be OK in the

all-white environment,” he says. “She knows who she is, she

can adapt.” Flowers, who didn't go to college, is proud of his daughter's

many accomplishments. “The sky's the limit for her. When you have

an education, you can write your own ticket. That's what you want for

your child. You live for that.”

That's what all parents want for their children. Black or white, urban

or rural, Vermonter or New Yorker. And it is what Gerald Garfin, principal

of Christopher Columbus High School, wanted for all his students: to enlarge

their ambitions, academically and geographically. To give them the best

possible education and a sense of their own potential.

When Garfin met Honeman at a meeting of the Foundation for Excellent Schools

in 2000, the two men immediately found common ground. It was Honeman's

desire to help make UVM a more diverse campus. Though Vermont, and UVM,

is predominantly white, its students will graduate into a world that is

multiracial, multiethnic, and multicultural.

“A diverse student community at UVM provides Vermont students with

the opportunity to interact with, and learn from students whose backgrounds

better reflect the world that our students will engage as graduates,”

says Honeman.

UVM was already recruiting in metropolitan areas, but with a northern

location and a predominantly white student body, its appeal was limited.

“We'd engage them halfway through their senior years and for them

Vermont seemed halfway to the North Pole,” he says. “This is

too late to make this kind of decision. But if we spent four years preparing

students to consider what choices they might have . . .”

Honeman doesn't have to finish the sentence, not today, and not for Garfin

five years ago. They were in perfect agreement. “He wanted access

to an inner city school,” says Garfin. “We wanted access to

a prestigious college.”

The type of program that both Honeman and Garfin were envisioning would

begin as early as ninth grade for students at Christopher Columbus. In

the early years, the focus wouldn't be on UVM in particular, but on applying

to college in general. “Especially in the freshman and sophomore

years,” says Honeman, “We're trying to be as marketing neutral

as possible. UVM is just used as an example, not the focus.”

Deborah Gale, a UVM admissions officer, explains that during a recent

trip to meet with ninth-graders at Christopher Columbus, “We had

them fill out a Common App [universal college application] and write an

essay. Then we critiqued it and showed them samples of good essays. Last

year, all the kids wrote me notes afterwards. I wrote personal notes back

to each of them.” This kind of repeated, personal interaction creates

relationships that can flower over time.

The program received an enormous boost when Alex Wilcox '94, an alumnus

who was director of business development at JetBlue Airways, heard about

the emerging program from Honeman. Impressed, he persuaded CEO David Neeleman

and his colleagues at JetBlue to provide corporate sponsorship in the

form of 200 annual free tickets between Burlington and the Bronx for use

by UVM staff and faculty as well as high school students and their families.

With the plane tickets, the path between UVM and Christopher Columbus

was laid down in air miles. Young urban kids began to see that Vermont

was not a foreign country, but a very appealing place, a mere 70 minutes

from JFK to BTV.

Donald Comras, college advisor for Christopher Columbus at the time, feels

the generosity of JetBlue was key to the program's early success. The

airline has continued its commitment of tickets and furthered it with

UVM scholarship support. “Those free tickets allowed our staff, our

students, and their families to see what the campus was like, what Burlington

was like,” he says. “One parent started crying when she came

to Burlington. She was so moved that her child would be allowed this opportunity.

For many of these families, this is the first generation to go to college.”

By the spring of 2001, 28 Christopher Columbus students had applied to

UVM, 22 were accepted and 13 enrolled. The partnership was up and rolling

or, in the words of Jerry Garfin - “During the first year, this thing

flew off the handle.”

In the Spotlight

It wasn't always easy. The first group of Columbus students received a

lot of attention, not all of it welcome, and wrong assumptions were sometimes

made.

“People assumed I wasn't qualified,” says Leniece Flowers. “Or

that I got a free ride.” This still rankles, even now, years later.

“I got here on my own merits. I'm not a charity case.” She,

like many of the partnership students, was always college-bound, did well

in high school, was accepted at many, if not all, of the colleges to which

she applied. (Of the original 13 students who enrolled at UVM, four graduated

in May and five more are on track to graduate.)

Miguel Garcia, another in the pioneering first class, found the culture

of Burlington to be something of a shock. A city boy accustomed to a “24-hour

lifestyle,” from his perspective the town closed up at dark, and

he admits that the cold affected him.

“UVM made me appreciate spring,” he laughs. “And New York

City!” Garcia, still looking hip in spite of the cold weather, wears

two earrings in his left ear, a nose stud, and a big black overcoat billowing

over his red sweatshirt and oversized jeans. Gray and red sneakers complete

the outfit. Garcia is committed to getting his diploma and continuing

his education, but last year he needed to take a break and return home.

He says he missed the bustle of urban life, missed the culture and the

food, missed the clubs and the nightlife.

An “out” gay man since his sophomore year in high school, Garcia

is very active in the gay student group and has struggled at times with

the visibility and the assumptions that being in the first partnership

group has engendered, both within the white and minority campus populations.

“I want to be known as Miguel, as an individual, not as Miguel from

Christopher Columbus,” he says. “Just cause we're people of

color doesn't mean we all have to stick together. A lot of my friends

are from Christopher Columbus, but there are other kids too. I hang out

with people who are gay, people of color, white. . . It's mixed. People

are people.”

Raphael

Okutoro feels the same way. Born in Liberia, Okutoro applied to, and was

accepted at, 11 other colleges, including Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University,

but a visit to UVM piqued his interest. Though his first impression of

the campus was - “kind of cold and very white” - he quickly

fit in. “I'm a very outgoing person. I try not to let things bother

me.” He joined Pi Kappa Alpha fraternity, where he was the only black

student. “I didn't feel different. We're all treated the same. With

respect.”

Raphael

Okutoro feels the same way. Born in Liberia, Okutoro applied to, and was

accepted at, 11 other colleges, including Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University,

but a visit to UVM piqued his interest. Though his first impression of

the campus was - “kind of cold and very white” - he quickly

fit in. “I'm a very outgoing person. I try not to let things bother

me.” He joined Pi Kappa Alpha fraternity, where he was the only black

student. “I didn't feel different. We're all treated the same. With

respect.”

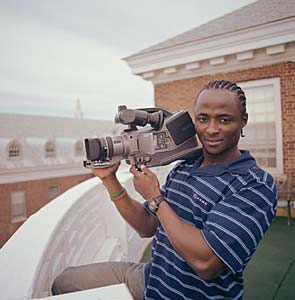

Okutoro, an environmental sciences major, has taken full advantage of

his years at UVM. He developed an interest in filmmaking, and has made

several films. He has served as orientation leader, resident assistant,

and peer advisor. He has done an internship with the admissions office

and served on a student advisory board - the list goes on and Okutoro's

admirers range far and wide.

Comras, his former college advisor at Columbus, says with a laugh, “Raphael

could become director of admissions tomorrow.”

Maybe someday, but not tomorrow. After graduation, Okutoro planned to

head for Hollywood. There, the former aeronautical engineering student

turned environmental engineer, turned filmmaker, wants to make it in the

movies.

Delivering on the Promise

The ALANA Student Center, under the leadership of director Beverly Colston,

has been a great support to many of the Columbus students as they've dealt

with the complexities inherent in being part of a minority community.

The unassuming one-story building on Redstone Campus has been a home away

from home and several of the students say that Colston has become as close

as family during their years at UVM.

This kind of support was critical during times of stress, when the students

were seeing that along with great educational opportunities, UVM offered

the chance for personal growth and for development of character - but

that some of these opportunities came from confronting difficult situations

and overcoming adversity.

In 2001, the freshman year of that first class from the Bronx, an incident

occurred that deeply disturbed the minority community. A white student

had hung a Confederate flag in his dormitory window, and though the administration

asked him to remove the flag, he refused. English Professor Emily Bernard

remembers it well. It was a time for the adults to show leadership, she

says, to be role models, but day after day, the flag hung there with all

its racist connotations, the object of controversy and discord.

“So you know what Leniece did?” Bernard asks. “She went

to the kid's room. She talked to him. Leniece was very gentle. Very grave.

I loved what it demonstrated about her. She'll always seek out her own

truth. She recognized the humanity of this kid. She looked him in the

eye, reasonable person to reasonable person. She did the gracious thing.

She was the mature grown-up. And she was a freshman! I was so impressed.”

Patty Corcoran G'88, assistant dean for student affairs in the College

of Arts and Sciences, has been another key advocate and friend for the

Columbus students. A counselor by training, Corcoran has worked on campus

for 24 years and has an unshakable devotion to the University and the

urban partnership.

“I have a special place in my heart for this program,” she says.

“It's easy to be a cheerleader for a program that gives us these

phenomenal students. They're really engaged, willing to be leaders on

campus. They are a delight to work with. It's very rewarding for all of

us, professionally and personally.”

The Urban Partnership Program also receives kudos outside the University.

In the fall of 2003, it was awarded Outstanding High School-College Partnership

Award from the New England Board of Higher Education. It's garnered wide

media attention, including front page coverage in The New York Times.

Beyond Columbus, that level of visibility has given UVM the sort of traction

it has never had with student recruitment throughout New York City and

other urban areas. “We've made amazing inroads,” says Gale of

UVM's Admissions Office.

But perhaps no one can appreciate the program as much as those on campus,

such as Corcoran, who grappled with the shantytowns on the University

Green, the occupation of the President's Office in April 1991, and other

moments in UVM's long struggle to build diversity.

“This is one of the things I am most proud of. Having been here during

the sit-ins and student protests and ending up here,” she opens her

arms to indicate the great students the partnership has brought the campus.

“I feel like this institution is evolving in terms of diversity.

We are finally delivering on the promise.”

The Only Way

And now it's the Columbus/UVM grads time to deliver on their own promise.

The University of Vermont has suited Leniece Flowers in many ways, and

she has embraced education as an avenue to a better life, not just for

herself, but also for others less fortunate than herself. “I want

to lift as I climb,” she says. “I think about my high school

experience and how things should have been different. Only a small proportion

of kids got to college. There should have been more.” She remembers

that there were often military recruiters on her high school campus, but

rarely did college reps come. “That tells you something about priorities.”

Bernard, who has gotten to know Flowers well over the past four years,

isn't surprised by her passion for education and equality. “She has

a huge sense of service,” says Bernard. “She's always aware

of her community and will always remember the people left behind. That's

so rare in the world now. For all her gifts, it's not easy to be a young

black woman.”

Even on the day before graduation, Flowers doesn't rest on her considerable

laurels. She has been patiently responding to requests for interviews

and photographs (that day the local newspaper ran her photograph on the

front page) and is looking forward to joining “Teach for America,”

where she'll work this summer before she begins graduate school. When

asked about a vacation, Flowers says she doesn't anticipate taking any

breaks until she gets her doctorate. Her career goal is to reform the

New York City public school system. That's going to take some preparation.

Bernard, for one, has confidence that Flowers will do whatever she sets

her mind to. “I have no doubt she'll have a public stage,” she

says. “She has great ideas about education - a sense of herself and

her role within the system. She wants to and can impact things on a national

level. My prediction: She'll be Secretary of Education in 30 years.”

“Education is power,” Flowers says. “It's the only way

for me. The only way I won't be denied opportunities.”