|

||

| uvm a - z | directory | search |

|

DEPARTMENTS Campaign

Update LINKS

|

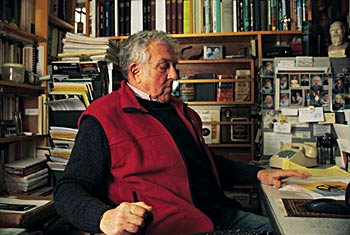

photograph by Rose McNulty

Enemies

from Within

by Lee Griffin

One

of the world’s foot soldiers, who may well be on his way to making

general in the war against biological invaders, Bruce Parker says, “We

feel our work has put UVM on the map from North Africa to the former

states of the Soviet Union. People there know about the University of

Vermont.” The putative General’s army is small and handpicked.

But, despite the range and power of their many opponents, he and his

troops are formidable front-liners in the battle against insect pests

that threaten food supplies and fledgling export economies in countries

of desperate need.

The Mission

Often on the road — more likely, in the air — on yet another

biological crime-fighting sortie, Bruce Parker and his warriors regroup

regularly in UVM’s Entomology Lab on Spear Street. Where, despite

the constant hustle that their schedules and grant-getting demand, these

otherwise peaceable souls willingly emerge from their paper-stacked,

refrigerator-carton cubbies to talk about the Middle East, Africa, pesticides,

and other topics near and dear to them. Toss out a question, and you

might take their voluble, overlapped responses for competition. You’d

be wrong. What Parker, Margaret Skinner, and Michael Brownbridge value

most is teamwork. If they cut off one another in mid-sentence on occasion,

it’s to finish the thought, add an anecdote, or pump-up the response

with a passionate stance about the places they’ve seen, the people

they’ve met, and the insect terrors they’re after.

Of late, their work has brought the researchers to the Middle East and

Africa, where seemingly endless news of strife and hunger casts ironic

shadows on the historical significance of these lands as the fertile

cradles of civilization and agriculture. The enemies are multiple, each

one compounding the problem, each one complicating the solution. And,

some of the lowliest enemies can be the toughest. To an outsider, the

problems seem overwhelming.

“The first time I went to Ethiopia,” says Brownbridge, a Briton

by birth, “I wondered ‘How the hell can I make a difference?’

You see how poor these people are first-hand, and you see every fifth

truck filled with U.S. grain. What does it matter what I’m doing?”

But, with subsequent visits, you get past that, he says. “In order

to get sustainable development…it’s got to be internal…not

me going in, doing something, then coming out.”

The researchers abiding commitment to improving international agriculture,

Skinner says, includes their work abroad, collaborations with other

scientists, and mentoring students from UVM and other countries. She

understands how life-changing working or studying in another country

can be. As an undergraduate at Ohio Wesleyan, the Vermont native had

to change her major from art to sociology in order to study in Beirut.

It was the defining moment of her undergraduate education and just the

beginning of international work for Skinner, who also spent eleven years,

three of them in Northern Ireland, working with mentally ill people.

Parker’s Pied-Piper-with-attitude M.O. overcomes an initial curmudgeonly

impression. His global connections and unabashed passion for the work

have enticed professionals like Brownbridge and Skinner to join the

team and have influenced a host of students to take the plunge into

other worlds. He occasionally revs up conversations with coach-like

enthusiasms, such as, “We are a dynamic, innovative group with

a very positive, can-do attitude. We don’t wait around — we

go for it.”

The

Enemy

The team also excels in another part of its mission — collaboration

with other scientists. They currently are working with colleagues in

countries of great need to dismantle a core problem — staple crop

devastation by insect pests. The order is tall, the collaborations spectacularly

refined, and the good guys are gaining.

For the past eight years, working in Syria, Iran, Central Asia, and,

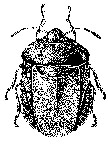

recently, in Afghanistan, the entomologists have set their caps to undo

the Sunn pest. Only a half-inch long, the dun-colored insect is a formidable

and — for farmers trying to combat it — a mortal enemy. The

Sunn pest damages cereal crops, especially wheat, by feeding on all

parts of the plant, but the greatest impact occurs when it feeds on

the developing grains. To enhance its digestive ability, it injects

an enzyme through its saliva that breaks down the grain’s gluten,

which, if the grain were milled, would render the flour unusable for

baking.

“We’re not talking about something incidental,” Parker

says of the Sunn pest, which he notes is expanding its range and is

now also on the border of Pakistan, a country of 153 million. “We’re

talking about a major, major problem, a major reducer of yield, of quality

in wheat primarily, but also barley.”

Longtime colleague Mustapha El Bouhssini, an entomologist from Morocco

who lives and works in Syria, says, “If as little as 2 or 3 percent

of the grain in a crop has been affected [by the Sunn pest], the grain

is unusable for baking.” The Sunn pest (Eurygaster integriceps)

affects about 37 million acres annually, and the bill for using chemical

insecticides against it each year is more than $40 million, he says.

The implications for a country like Afghanistan are enormous. In addition

to its natural hazards of drought, earthquake, and lack of potable water,

25 million people depend on the 12 percent of arable land, and the pest

is eating its staple crop. Syria’s landmass is primarily desert.

Slightly larger than North Dakota, it must feed 18 million people. Twenty-six

percent of its land is arable.

And, in the category of the cure is worse than the disease, eradication

of the Sunn pest and other serious pests has attracted another enemy,

wholesale use of chemical pesticides. In countries desperate for quick

fixes on these problems, officials often see pesticides as magical cures

and because the government usually pays for the cure, the farmer willingly

uses the chemicals. “You have to do it (spray) every year,”

El Bouhssini says, and the chemicals “kill bees, pollute water.”

Skinner adds, “Using insecticides on the Sunn pest has disrupted

the natural enemy complex, because they also are killed. …And,

Sunn pest can develop resistance to pesticides.”

The Weapon

The skirmishes in which the UVM trio engages pit naturally occurring

enemies like fungi against insect pests, a key component in a process

known as Integrated Pest Management. They and the other ten scientists

and graduate students in the Spear Street lab develop effective biological

agents to control or destroy insect aggressors in agriculture, forests,

and greenhouses. As the name suggests, IPM uses a variety of approaches,

but the goal is to control the damaging pest without damaging anything

else and to develop those controls so that farmers, foresters, and growers

can use them, economically, and in a way that is environmentally sound

and sustainable.

Their research on fungal pathogens as part of an IPM approach has pitted

them against such enemies as the hemlock wooly adelgid, which originated

in the Far East and traveled westward, without any natural enemy to

keep it in check; the pear thrips, which severely damaged sugar maple

trees in Vermont in 1988 and 1990; and the western flower thrips, which

is a pest of global significance in flower and vegetable crops.

Parker and Co.’s investigation into pear thrips is a model of the

IPM approach. The researchers studied the pest in its origins and sought

and identified pathogenic fungi that worked against the thrips. Then

they developed a way to mass-produce the fungi using old maple leaves,

thus arming Vermont sugar makers with grow-their-own, low-tech ammunition.

The scientists’ international reputation is a direct outgrowth

of their continuing work to aid Vermont and other U.S. farmers, foresters,

and growers.

Brownbridge currently is wrapping up work on two USAID projects in Africa.

He worked with Kenyans to develop a sustainable IPM program that small

farmers with few resources could use to defeat the African armyworm,

a migratory pest that ranks second only to the voracious locust in the

level of damage it causes in staple food crops and arable grazing land.

He’s also completing work with the Ethiopian Agriculture Research

Association to train citrus growers in the use of biological controls

and to assist the fledgling greenhouse industry.

For the past eight years, the entomologists have dedicated their vast

experience and knowledge of IPM practices to eradicating the Sunn pest.

Phase one of the project took about three years, during which the researchers

collected fungi that occurred in the pest’s overwintering sites

throughout its whole range — Syria, Turkey, Iran, Uzbekistan, and

Kazakhstan. “The insect lives probably nine months of the year

in…the foothills of the fields, under litter,” (dead leaves

and twigs), Skinner says. They found some fungi on the cadavers of the

Sunn pest, but lab tests were needed to determine if the fungi killed

the pest or were merely opportunistic.

When the lab results proved positive, it was back to the field, where

— if the fungi didn’t disappoint — the scientists would

devise a way to apply it. “One advantage of using the overwintering

site for treatment,” Skinner says, is that there is time for it

to work, as opposed to using it in the wheat fields, when the damage

may already be done. At first, Skinner and Parker took dry fungal spores,

mixed them with water and sprayed the mixture on the Sunn pest’s

overwintering sites. Local residents were quick to teach them a lesson

that Skinner translates into American vernacular: “Hey you guys,

we’re in the Middle East. We don’t have a lot of water.”

They focused instead on using a nutrient-based granular formulation,

which means, Skinner explains, “growing the fungus on a solid substrate

like rice or millet.” Population is in an abundant supply, so these

countries “can pay someone to throw the inoculated base around

the sites,” she says. The biggest question was whether the formula

would penetrate the litter to where the insects snoozed.

Within a year, they had the answer. The fungi had grown all over the

litter and — despite a rainy winter and a summer with 115-degree

temperatures — the fungi continued to grow and kill the Sunn pest.

Parker says getting the fungus to persist is all-important. “Next

season, new insects will go there and will be killed, and what you’ve

got is sustainable.”

The Coalition

Parker, Skinner, and Brownbridge are not danger junkies, but they don’t

share the fears many of us might have in traveling abroad, particularly

in the Middle East. They’re also not alone. “We are very well

taken care of,” Parker says. “We work with one of the finest

international institutions in the world. He adds: “I had my family

there [Syria] for a whole year during sabbatical. I was in Lebanon during

9-11. We work in Iran — we’re 100 percent supported from the

time we reach the Iranian airport. We were well taken care of in Afghanistan,”

he says, where he and Skinner worked just south of its politically unstable

capital, Kabul, this past year. However, the hotel they stayed in was

bombed recently, he concedes.

The lubrication for such smooth sailing in potentially troubled waters

is ICARDA, an overarching international organization dedicated to improving

the welfare of people in the dry areas of the developing world through

research and training to increase local productivity. The International

Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas, its full name, is

headquartered in Aleppo, Syria. “This isn’t a dinky place,”

Parker emphasizes. “It’s a huge facility with expertise from

all over the world.” El Bouhssini says about 45 nationalities are

represented among 70 or so scientists and grad students from all over

the world. “We have about 500 support staff and thousands of dailies

that help on the farm.”

El Bouhssini, one of ICARDA’s senior scientists, has worked with

UVM’s entomologists for eight years. He also spent the fall semester

at UVM deepening his knowledge of IPM. “When we started this association,

the concept of IPM was completely new in the region, so a very interesting

area for us,” he says. Of the Sunn pest project, he says, “I

am amazed at the progress in a relatively short time.”

Referring to ICARDA, Parker says, “All the scientists there are

working on a single goal — to improve the quantity and quality

of crops in the developing world to feed hungry people. …Our little

niche is IPM, and we’re part of the scientific staff when we’re

there. We know the institution and region, and before we go, it’s

outlined exactly what we’re going to do.”

What they do is fairly intensive. Former graduate student Jane Stewart,

who worked in Syria with Parker and Skinner, says fourteen-hour days

in the lab and the field were the standard. The group had only five

days off in the six weeks she was there. Her memories, like all the

UVM researchers, return often to the people. “Everyday they (the

local people with whom she worked in the field) would invite me to eat

with them and offer clothing when the temperatures dropped. It snowed

a couple of days while we were in the field, and all the women had on

their feet were plastic shoes, kind of like jellies. …I had on

gloves and boots and a good rain jacket. They tried to give me clothing.

The women were amazingly tough and smart.”

Skinner, often the only woman in a working group, echoes Stewart’s

sentiments. “People are so nice in the Middle East. I haven’t

had any bad experiences. They don’t like what’s going on with

Bush, but they are friendly, curious, and like American style…the

fact that we’re appreciative and we treat people like people, not

on a class basis.”

In respect for different cultural mores, Skinner says, she wears clothing

appropriate to each country. “In Syria, you can wear anything you

want. I wear more than I’d wear at home, no shorts or short sleeves,

and I wear a skirt or pants. In Iran, I wear pants and a headscarf at

all times. I wear a jacket or coat that comes down to below my knees.”

At a conference last year in Iran, Skinner, the only woman, unwittingly

tested Middle Eastern tolerance for liberated Western women. While she

was presenting, her headscarf slipped off. Her expletive (deleted) was

decidedly not within the culture’s mores for women, but it broke

the ice. “There were about 25 men at the conference,” Parker

says, “and they all cracked up.”

The Victory

With world population doubling every forty years, no end in sight of

civil strife and war, and the United States pushing chemical insecticides

throughout the world, the ICARDA and UVM scientists won’t soon

be out of challenges. But, the four find many reasons to be optimistic

and encouraged about their mission.

Skinner, angry as she is at the deception of the pesticides-cure-all

approach, sees hope for reversing that and for a more peaceful world

through international experience. “People don’t understand

that Syria is made up of…real nice people, not dangerous terrorists.

…The more interactions we have, the more we’re going to get

along.”

Brownbridge believes the strict rules set by the European Union on the

way agricultural imports are produced will have a salutary effect in

emerging export countries like Ethiopia. Growers there will benefit

from rules on “fewer pesticides, mandatory safety equipment, minimum

salary requirements, better housing standards, and access to health

care,” he says. “The positive effects ripple out to the whole

community. A farm I went to employs 2,000 people, each married, with

kids…there are the contractors and suppliers and their families.”

El Bouhssini doesn’t have to look farther than the farmers he works

with and for as confirmation of all their work. “Farmers are changing,

participating, are adopting new technologies,” he says. And the

best news of all, he says, “This new approach is working and is

better than the old.”

Parker believes they’re close to winning the Sunn pest wars. “We’re looking at potentially nine months to a year now when we’ve got this part of the problem licked, which is fantastic.”

There won’t be a “Mission Accomplished” banner hanging

on their lab, and the entomologists will remain anonymous to almost

all their benefactors. But the effects of this collaborative project

will ripple through many countries and will be a victory on the magnitude

of a world war détente.