| SEARCH |

| UVM A TO Z |

| WHITE PAGES |

| UVM HOME |

Vermont teachers who study Asian history and culture at the source are introducing their K-12 students to all things East

On a late September morning, Brad Blanchette ’71, G ’85 and Alison

Fisk ’93 lead their class of forty-two ninth-grade students in

a discussion of The Good Earth — Pearl S. Buck’s novel about pre-Revolutionary

China. Fisk expounds on the literary devices in Buck’s novel before

Blanchette introduces topical issues that range from Chinese farming

practices and the abandoned practice of female infanticide to

the country’s current “one child” policy. Blanchette — who spent

three weeks last summer in China through UVM’s Asian Studies Outreach

Program — has physically transformed this English and social studies

classroom at Colchester High School, covering the walls with calligraphy

scrolls, Chinese artwork, and a poster of moon-faced Chairman

Mao much like the one that looms over Beijing’s Tiananmen Square.

On a late September morning, Brad Blanchette ’71, G ’85 and Alison

Fisk ’93 lead their class of forty-two ninth-grade students in

a discussion of The Good Earth — Pearl S. Buck’s novel about pre-Revolutionary

China. Fisk expounds on the literary devices in Buck’s novel before

Blanchette introduces topical issues that range from Chinese farming

practices and the abandoned practice of female infanticide to

the country’s current “one child” policy. Blanchette — who spent

three weeks last summer in China through UVM’s Asian Studies Outreach

Program — has physically transformed this English and social studies

classroom at Colchester High School, covering the walls with calligraphy

scrolls, Chinese artwork, and a poster of moon-faced Chairman

Mao much like the one that looms over Beijing’s Tiananmen Square.

Next on the syllabus is a close study of a dozen poems from the Tao Te Ching, “the essence of Tao,” explains Blanchette, attributed to sixth century B.C. philosopher Lao Tsu. Breaking into small groups, the students analyze the poems while their teachers provoke questions.

“Taoism tells us to be like an uncarved block,” Blanchette suggests. “How does that philosophy differ from Confucianism?” “Taoism is the concept of infinite possibility,” a serious-looking boy pipes up. “Confucianism is having your identity carved by society,” a slight blonde girl answers.

Blanchette nods enthusiastic assent. “Be like water, not stone,” he quotes from a poem, and strikes a martial arts pose. “Taoism tells us to be flexible. In the Japanese martial art of Aikido, flexibility teaches you to use your opponent’s strength against him.”

As homework, the students will write an original poem in the Taoist style. They have already read Confucius’s Analects and Benjamin Hoff’s The Tao of Pooh this semester, but no one is complaining about the workload. In fact, they seem fascinated by the subject matter.

Blanchette, who was Vermont Teacher of the Year in 1986, “shares a lot of anecdotes about China that the students really get into,” Fisk explains to a visitor as the dismissal bell rings and the students file out.

“I can talk from real experience now about things that used to be abstract,” Blanchette agrees. “I also have a much better idea of how we can shift the course material to cover more on modern, post-Revolutionary China.” He holds up a copy of Red Scarf Girl, Ji Li Liang’s memoir of her life during the Cultural Revolution, which will be assigned later in the semester.

Blanchette and Fisk began revamping this “Cultures in Crisis”

course after taking a graduate course in Asian Studies at UVM

two summers ago. While Blanchette continued those studies in China

last July, Fisk stayed home with the baby she and her husband,

UVM medical student Peter Fisk, welcomed in May.

Blanchette and Fisk began revamping this “Cultures in Crisis”

course after taking a graduate course in Asian Studies at UVM

two summers ago. While Blanchette continued those studies in China

last July, Fisk stayed home with the baby she and her husband,

UVM medical student Peter Fisk, welcomed in May.

“We should be studying China like crazy in this country,” Blanchette insists, noting that China’s enhanced trade status with the United States, and Asia’s growing importance as a global economic power, mean that more Americans will interact with Asians in the future.

According to surveys conducted by the New York-based Asia Society, 70 percent of U.S. students believe studying Asia will prove beneficial to their careers. Yet only nine thousand Americans study Asia in school, and just 26 percent of college-bound students know which body of water divides the United States and Asia. Those statistics become less surprising when it’s considered that textbooks usually exclude Asia or portray its history and people in distorted, stereotyped ways, and only half of U.S. social studies teachers have taken even one Asia-related course.

Hoping to address that problem, more and more U.S. colleges and universities — including Harvard, Stanford and Yale — are helping teachers update curricula on Asia and sponsoring overseas programs for teachers and students to learn first-hand about the continent that is home to half the world’s population. “Our program is the most comprehensive, and the only one with a statewide mission,” says Juefei Wang, director of UVM’s Asian Studies Outreach Program (ASOP).

Wang helped launch the program fifteen years ago after leaving

Beijing to pursue a second graduate degree at UVM. With ongoing

financial support from the Freeman Foundation, the program coordinates

school-to-school teacher exchanges between China and Vermont;

helps teachers develop standards-based K-12 curricula; and hosts

overseas outreach courses that annually send about 110 teachers,

administrators and high school students to China and Japan. While

the ASOP network currently includes 123 Vermont schools and 270

educators from Windham to Brattleboro, Wang’s mission is to integrate

Asian Studies into the formal curriculum of all 612 Vermont schools.

Wang helped launch the program fifteen years ago after leaving

Beijing to pursue a second graduate degree at UVM. With ongoing

financial support from the Freeman Foundation, the program coordinates

school-to-school teacher exchanges between China and Vermont;

helps teachers develop standards-based K-12 curricula; and hosts

overseas outreach courses that annually send about 110 teachers,

administrators and high school students to China and Japan. While

the ASOP network currently includes 123 Vermont schools and 270

educators from Windham to Brattleboro, Wang’s mission is to integrate

Asian Studies into the formal curriculum of all 612 Vermont schools.

Often, his best salespeople are the enthusiastic participants. Blanchette, for instance, credits colleague Steve Fiske for igniting the Asian fever that has swept through Colchester High School. In 1988, Fiske was among the first Vermont teachers to visit China in the six-week prototype for ASOP’s current program. Upon his return, Fiske enlisted Blanchette, his team teacher at the time, to help develop an Asian Studies curriculum that evolved first into an elective course, then into a full semester of Asian Studies that is now mandatory for all CHS freshman — nearly two hundred of them this year. Originally focused solely on China, the course now includes study units on India and Japan. “We can’t cover all of Asia in one semester,” Blanchette admits, “but we’re always committed to doing more.” More, however, doesn’t always mean maps and textbooks. The latest endeavor under way at CHS was inspired, says Blanchette, by one of his most memorable experiences in China — learning shufa, the Chinese art of calligraphy.

“Americans don’t think of calligraphy as an art form,” he says,

“but it is an art that takes a lifetime to learn, and that encompasses

poetry, Taoism, and even martial arts.” The calligrapher’s stance

and how he maneuvers the brush over rice paper, explains Blanchette,

mimics the postures of martial arts. And as a calligrapher inscribes

scrolls with Chinese poetry, he also becomes one with the flow

of the present moment, or is “in the way of the Tao.”

“Americans don’t think of calligraphy as an art form,” he says,

“but it is an art that takes a lifetime to learn, and that encompasses

poetry, Taoism, and even martial arts.” The calligrapher’s stance

and how he maneuvers the brush over rice paper, explains Blanchette,

mimics the postures of martial arts. And as a calligrapher inscribes

scrolls with Chinese poetry, he also becomes one with the flow

of the present moment, or is “in the way of the Tao.”

At Yunnan Normal University in Kunming, Blanchette and his fellow Vermont teachers studied with one of China’s most famous calligraphers, Cheng Dichao. After the formal lesson, the master created individual scrolls for each teacher, inscribing them with traditional Chinese poetry that uncannily captured each person’s personality, says Blanchette.

“He did mine in what’s called ‘wild script,’” he explains. “While my friends might consider me set in my ways, I like to think the calligrapher understood my hidden free spirit. The poetry he chose was about ascending a mountain in fog, and trusting that the path will be made clear. Perhaps this would have fit anybody, but I do tend to start on things blindly, trusting that I’ll find my way. And it’s worked so far.”

“Mine was the last scroll of about fifteen to be created,” recalls Bill Rich, director of CHS’s humanities department. “So my expectations weren’t high. But the poetry the teacher selected, which was about being centered in feelings of well-being, peace and harmony, was perfect for me.”

Before heading back to Vermont, Rich and Blanchette purchased

brush pens, ink, ink stones, and chops (intricately carved soapstone

used to create a calligrapher’s unique signature), volumes of

Chinese poetry and calligraphy — the tools they are using to pilot

a study unit on Chinese calligraphy, painting and art for all

CHS freshmen this year.

Before heading back to Vermont, Rich and Blanchette purchased

brush pens, ink, ink stones, and chops (intricately carved soapstone

used to create a calligrapher’s unique signature), volumes of

Chinese poetry and calligraphy — the tools they are using to pilot

a study unit on Chinese calligraphy, painting and art for all

CHS freshmen this year.

“If we can put a brush in the kids’ hands,” says Rich, “let them make a little ink, and experience how it feels on the paper, they’ve learned something. We can also use this as an opportunity to show them the differences in philosophy between Western and Eastern art.

“When an American artist wants to paint a tree, for instance,” explains Rich, “he sets his easel up near the tree and looks back and forth from tree to canvas until the painting is complete. A Chinese artist, on the other hand, will go out and study that tree all day, come home and think about it and paint it from memory.”

In early November, Blanchette and Rich enlisted Chinese teachers Xue Rumei and Yu Weixing to get the project off to an authentic start. After grasping the basics — how to hold the brush and coat it with the correct amount of ink — the students were soon practicing four basic brush strokes that comprise many of the characters in this art form that dates back several thousand years.

“Your dot should look like a teardrop, or a drop of rain,” instructs Rumei while Blanchette distributes Chinese calligraphy poems, pausing to read a few in English. “It’s only recently that these poems have been translated correctly,” Blanchette explains, noting that Chinese poetry eschews personal pronouns for a multiple perspective that “allows you to enter the poem and discover your own meaning.” As the students roll up their sheets of rice paper at the end of class, a few make plans to practice drawing characters together after school.

Rumei and Weixing are two of the five Chinese teachers ASOP has placed in Vermont schools for the 2000-2001 academic year, teaching in Westford and Richmond, respectively.

Judy Prince, who is Westford Elementary School principal and was named Vermont Principal of the Year in November, jumped at the chance to introduce her 333 pre-kindergarten through eighth-grade students to Chinese history, culture and art.

“It didn’t take long to see how many ways Rumei could enrich education,

especially in a rural school in a state that lacks diversity,”

says Prince. “The kids reach out to her in different ways,” she

says, noting “the third- and fourth-graders especially enjoyed

working with her on Chinese opera masks.” In addition to teaching

units in virtually every subject at Westford Elementary, Rumei

— a Beijing native who is living with Prince and her family during

her year abroad — plans to teach an origami class for the Westford

community and regularly visits Milton and Essex schools.

“It didn’t take long to see how many ways Rumei could enrich education,

especially in a rural school in a state that lacks diversity,”

says Prince. “The kids reach out to her in different ways,” she

says, noting “the third- and fourth-graders especially enjoyed

working with her on Chinese opera masks.” In addition to teaching

units in virtually every subject at Westford Elementary, Rumei

— a Beijing native who is living with Prince and her family during

her year abroad — plans to teach an origami class for the Westford

community and regularly visits Milton and Essex schools.

Although the variety of Asian-related curricula is as diverse and varied as the personality and interests of each teacher, hands-on activities like origami, painting, and mask making are popular approaches for elementary and middle school students.

A 1997 trip to China inspired art teacher Catherine Ring to engage all sixty-five students at Woodbury Elementary — a small, K-6 school at the edge of Vermont’s Northeast Kingdom — in Asian-themed activities for the entire academic year. Those activities culminated with a festival for the whole community complete with paper dragons made by the students and authentic dances taught by a Chinese community member.

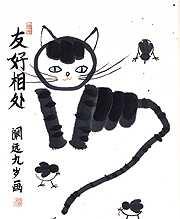

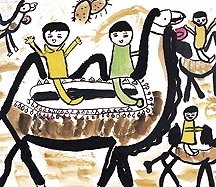

And at Berlin Elementary School, Ring and her colleague Brenda Seely created an art project that is reaching far beyond the perimeters of their classrooms — a traveling exhibit of forty-five paintings by Chinese children that debuted last January in Berlin and has been booked solid in Vermont schools and public venues ever since.

The project began almost by accident, Ring explains. Two years ago, she and Seely took forty-five pieces of Vermont students’ artwork to China, and presented them to the president of the teachers’ university in Qufu. “He was so taken with the paintings that he exhibited them on campus,” says Ring, “and when he visited Vermont a year later, he brought us the Chinese children’s calligraphy and paintings we used to create our exhibit.”

Media and cultural themes inherent in the Chinese paintings vary greatly from Vermont children’s art, “but there are so many elements that transcend cultures,” Ring says. “The Chinese children’s humor and the things they like to do, really come through.” Consequently, Vermont and Chinese students are learning they aren’t so different—a lesson, says Ring, valuable to students of all ages.

“My experiences in China made me a better teacher,” she asserts, “one who is more careful about questioning stereotypes and over-generalizing when teaching about other cultures. In a world full of conflict, learning about and gaining respect for another culture can only lead to good.” VQ