THE PROSPER VALLEY VIGNETTES:

Of an Unusual Wealth - Prosper Valley Vegetation

I was tromping around the Barnard Gulf on what must have been the hottest, muggiest,

and buggiest day of the summer. The haze hung in the air, the sweat ran down my

back, and the black flies went wherever they pleased. And, unfortunately, it also

happened to be the first (and only) day I wore shorts. However, had the heat, humidity,

and biting insects been the only things to assault my senses that day I might have

forgotten the experience altogether, but this was one to remember. It became the day

that I found myself stuck between a rock and a hard place. The "rock" was a steep

bedrock slope and the "hard place" was a tremendous patch of stinging nettle plants. I

paused to weigh my options—confronting the nettles seemed like a better one than

scaling the steep, rocky slope. After I made it through the first patch of biting plants

and saw another ahead, I realized that it would be equally bad to go back as to keep

going. So, I let my tingling legs make the decision. The slope I started up included

sections of vertical bedrock outcrops broken by sections of relative flat. As I made my

way through the rough terrain, I started to notice some of the herbaceous plants that

carpeted the slope.

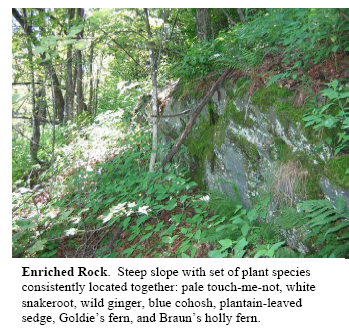

There were dense blankets of pale touch-me-nots and white

snakeroot, pockets of wild ginger and blue cohosh, and clumps of

plantain-leaved sedge, Goldie's fern and Braun's holly fern.

Though this was the first time I had seen these two relatively rare

ferns, I'd seen the other plants at various locations throughout the

Prosper Valley—and they were always together. Why was I

seeing these species here on this rocky slope? And, why were they always together?

There were dense blankets of pale touch-me-nots and white

snakeroot, pockets of wild ginger and blue cohosh, and clumps of

plantain-leaved sedge, Goldie's fern and Braun's holly fern.

Though this was the first time I had seen these two relatively rare

ferns, I'd seen the other plants at various locations throughout the

Prosper Valley—and they were always together. Why was I

seeing these species here on this rocky slope? And, why were they always together?

The answer is wealth. Not wealth in the way we humans may think of it—possessions, property, or riches, but wealth according to plants—nutrient wealth. Because soils form from weathering rock, whatever minerals are sequestered within the rock contribute to the soil; soils forming atop parent material rich in nutrients are enriched with these same nutrients. Certain chemicals that exist in rocks, like calcium, are essential nutrients for plant growth. Thus, soils differ in the quantity and quality of nutrients they offer plants based on the underlying rock. Furthermore, soils containing calcium not only physically supply the calcium for plant growth, but also chemically alter the soil environment so that plants can actually use the calcium. These soils are therefore more fertile, or rich.

But, how does this resolve why certain plant species tend to grow together? As it turns out, the plant species I came across that day in the Gulf, and elsewhere throughout the Valley, prefer enriched soils and are the most competitive plants in them. Hence, one can draw inferences about the soil of a particular site if these plants are growing there. Their competitive advantage causes them to be known as rich site indicators.

I'd established that the soil on this site was rich, but I hadn't yet discovered its source of wealth. As I balanced myself on the steep Gulf slope, I looked around. The rock I'd seen throughout the Valley that had formed partly from calcium-rich shells of ancient sea creatures formed the steep sides of this hill. It looked like a pocked, Martian rock to me, and was an "impure limestone or marble" to geologists. Evidently, the soil on the hillside was rich partly because the underlying bedrock contributed calcium to it, which enabled this set of rich site indicator plants to thrive.

Plants that indicate something about their physical surroundings are not limited to rich

sites. Many herbaceous plants, shrubs, and trees throughout the Prosper Valley grow in

similar associations—called natural communities—based on different aspects of their

surroundings, like moisture, enrichment, elevation, amount of sunlight, and disturbance

regime.

If you walked from the farthest reaches of the Gulf Brook

headwaters to its outlet at the Ottauquechee River you would come

across countless different natural communities.

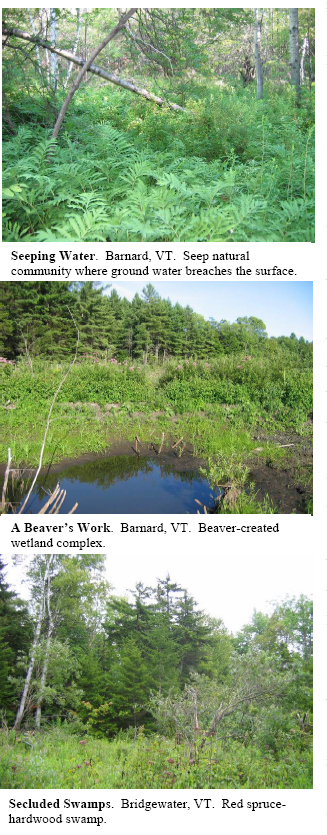

In the hills, you might chance upon seeps, where groundwater breaches

the surface, soaking your feet and supplying nutrients from the rock beneath to surrounding vegetation.

In the hollows, you could drench

your feet in beaver-created wetlands where the beavers' cycle of dambuilding

and abandonment creates wet meadows of young willow trees

and other water-tolerant plants. In the colder highlands, you would hike

through shadowy forests of red spruce, red maple and American

beech trees. In the lowlands, you would hike around red sprucehardwood

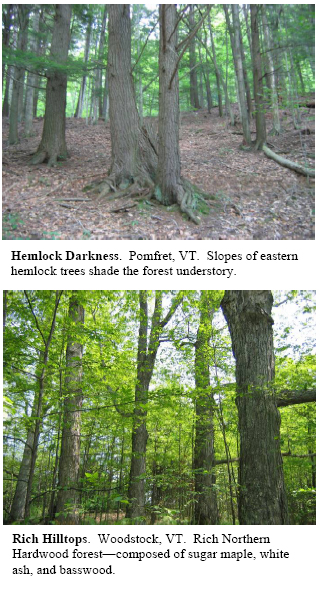

swamps teeming with life. On rich ridges, you might come

across sugar maple, white ash and basswood forests, with a carpet of

sedges. In the fertile valleys, you might saunter through belts of airy

silver maple floodplain forests, with tall ferns blanketing the ground. On the western-facing slopes, you by

chance enter into the darkness of a hemlock forest, with only yellow

birch bark acknowledging the sunlight. On the flats, you by chance

catch the still eyes of a wood frog peeking out from sensitive fern and

skullcap cover along the margin of an ephemeral pool. And, all the while,

you havenít left the Prosper Valley. You have, however, encountered

significant biological diversity—biological diversity that, for me, was

"the spice of life" last summer. I certainly would rather face a choice

between a rock and a hard place than to have no choice but face the same landscape every way I turn.

In the hollows, you could drench

your feet in beaver-created wetlands where the beavers' cycle of dambuilding

and abandonment creates wet meadows of young willow trees

and other water-tolerant plants. In the colder highlands, you would hike

through shadowy forests of red spruce, red maple and American

beech trees. In the lowlands, you would hike around red sprucehardwood

swamps teeming with life. On rich ridges, you might come

across sugar maple, white ash and basswood forests, with a carpet of

sedges. In the fertile valleys, you might saunter through belts of airy

silver maple floodplain forests, with tall ferns blanketing the ground. On the western-facing slopes, you by

chance enter into the darkness of a hemlock forest, with only yellow

birch bark acknowledging the sunlight. On the flats, you by chance

catch the still eyes of a wood frog peeking out from sensitive fern and

skullcap cover along the margin of an ephemeral pool. And, all the while,

you havenít left the Prosper Valley. You have, however, encountered

significant biological diversity—biological diversity that, for me, was

"the spice of life" last summer. I certainly would rather face a choice

between a rock and a hard place than to have no choice but face the same landscape every way I turn.