Santa Fe

“The City Different”

A Brief Look at

Preservation

Sara Casten

Funded in part by the Historic Preservation Program at the University of Vermont

Table

of Contents

Acknowledgements………………………………………………………….1

The

Santa Fe Style and Materials……………………….…………...….…..2

The

History of Preservation and the Work of John Gaw Meem……………5

The

Historic Design Review Board…………………………………………8

Current

Conservation Practices…………………………………………….14

Preservation

Organizations………………………………………………...19

The

Future of Santa Fe……………………………………………………..25

Executive Summary

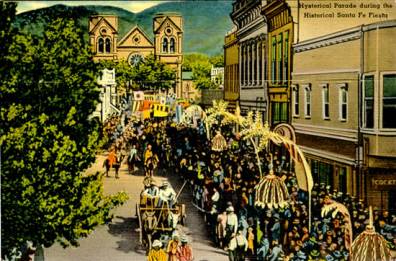

Santa Fe, the city different, in the land of enchantment draws thousands of tourists, artists, retirees, and asthmatics to name a few to take in the unique skyline, dry desert climate, rich red and blue colors. Founded in 1609 it is the country’s oldest capital city. It has been defined by its “Santa Fe Style” of architecture made popular by architects Isaac H. Rapp and John Gaw Meem in the early and mid twentieth century. The Santa Fe Style includes both the Territorial and Spanish Pueblo Revival.

This brief contains seven interviews with members of the city’s preservation community. The interviews conducted, and the organizations visited give an overview of the practices in Santa Fe. Focusing mainly on the Downtown and Eastside Historic District, the first district formed in Santa Fe. While their backgrounds and opinions differ, there is no question that Santa Fe is a unique and beloved city.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to Jake Barrow, Elaine Bergman, Ed Crocker, Jane Farrar, David Rasch, Francisco UviĖa Contrers, Thomas Visser, Nancy Wirth, Cornerstones Community Projects, Historic Design Review Board, Historic Santa Fe Foundation, The City of Santa Fe, NM, and the University of Vermont Historic Preservation Program.

The Santa Fe Style and

Materials

The current principle styles of architecture

that make up the Santa Fe Style are the Spanish Pueblo, the Territorial, and

revivals of both styles. The

Spanish Pueblo Revival evolved out of the combination of the early Native

American adobe building and architecture brought over by Spanish settlers. The Territorial Style, which gets its

name when New Mexico was just a territory of the United States, grew out of the

westward expansion along the Santa Fe Trail in the mid nineteenth century.

The current principle styles of architecture

that make up the Santa Fe Style are the Spanish Pueblo, the Territorial, and

revivals of both styles. The

Spanish Pueblo Revival evolved out of the combination of the early Native

American adobe building and architecture brought over by Spanish settlers. The Territorial Style, which gets its

name when New Mexico was just a territory of the United States, grew out of the

westward expansion along the Santa Fe Trail in the mid nineteenth century.

One of the earliest examples of the fusion of the Spanish Mission Style and the Pueblo is the San Esteban Mission, Acoma Pueblo built between 1629 and 1644 (above Fig. 1). It is built by the Spanish to convert the native peoples to Christianity, as one of the main purposes of their settlements is to spread religion. The style is considered to be more inviting if it contained elements of the familiar.[1]

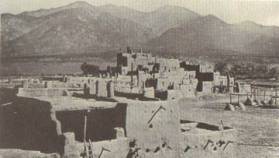

The Traditional Pueblos are small rectangular connected units that are designed for communal living. The walls are made out of adobe that is essentially a simple mud construction. The floors are earthen with a flat roof supported by vigas or pine logs (above Fig. 2). These dwellings typically did not have foundations. When the Spanish arrive they adopt much of this building type. They added the technology of shaping the adobe into bricks, which could then be dried in the sun. They also began building on foundations instead of directly on the ground. Other additions include portals to the exterior elevations and inner courtyards that are prevalent in European architecture. Neither of these elements is seen in traditional adobe structures.[2]

The mid 19th century brought trains and westward expansion, in New Mexico the Santa Fe Trail opened up as a merchant route. From this growth the Territorial Style develops. Materials are being shipped for construction use throughout the country’s new territories, which is how the style eventually gets its name. Some of these buildings are constructed with hard-burned brick. However, in the earlier stages of this style it is still too expensive and most builders just used this material to protect the adobe beneath. The brick is often laid in decorative patterns which became the first indication of the style, and handmade windows are replaced by new milled ones. The most affective change in construction is the beginning use of lime plaster, again to protect the adobe. Also the addition of the Territorial style porches, usually the full width and often full height of the building, are a character defining feature of the style.[3]

During the late 19th century Santa Fe began to grow as most of the country did. Red brick is becoming a more prevalent building material, and Mansard roofs are constructed indicative of the 2nd Empire Style. However, at the beginning of the 20th century a group of artists and architects, especially Sylvanus G. Morley, Jesse L. Nusbaum, and Isaac Hamilton Rapp, began to reverse this “Americanization.”[4] This is when the Santa Fe Style truly emerged. This informal committee convinced the community to return to their architectural roots. From numerous letters, designs and examples of existing buildings—mainly designed by Rapp a new style is created.

Today the Historic Ordinance, first written by John Gaw Meem and other prominent city members in 1957, prohibits the construction of buildings in styles other than the Spanish Pueblo Revival and the Territorial Revival Style in the Historic Districts.

The

History of Preservation and the Work of John Gaw Meem

The Santa Fe Style begins to take shape in

1912 with Sylanus G. Morley and Jesse L. Nusbaum. Morley is hired to redesign the portal for the Palace of

Governors located in the Plaza, the heart of Santa Fe’s Downtown. In 1912, the current portal reflected the

Territorial Style added to the building in the mid to late 19th

century. Morley sought to return

to the faćade to what he thought it originally looked like, which is mainly

based on conjecture. At the same

time Nusbaum is designing an exhibition of architecture to spark interest in a

new Santa Fe Style and to help advertise the city as the new “tourist center of

the southwest”[5] Nusbaum has been desperately searching

for a style that he thought defined Santa Fe, he found it in Isaac Hamilton

Rapp’s work and thought his Colorado Supply Company Store in Morley, Colorado

to be the prefect example. Nusbaum

writes to Rapp praising his work and asks for his assistance in this endeavor,

and Rapp replies with a water color (above Fig. 3) of the building for the

November architecture exhibition.[6] Shortly after, Rapp designed the Museum

of New Mexico built in 1915, one of the earliest examples of the new Santa Fe

Style. It is easy to see Rapp is drawing

his inspiration for museum from San Esteban Mission, Acoma Pueblo. In 1920, Rapp’s Architectural firm

leaves Santa Fe paving the way for John Gaw Meem.

The Santa Fe Style begins to take shape in

1912 with Sylanus G. Morley and Jesse L. Nusbaum. Morley is hired to redesign the portal for the Palace of

Governors located in the Plaza, the heart of Santa Fe’s Downtown. In 1912, the current portal reflected the

Territorial Style added to the building in the mid to late 19th

century. Morley sought to return

to the faćade to what he thought it originally looked like, which is mainly

based on conjecture. At the same

time Nusbaum is designing an exhibition of architecture to spark interest in a

new Santa Fe Style and to help advertise the city as the new “tourist center of

the southwest”[5] Nusbaum has been desperately searching

for a style that he thought defined Santa Fe, he found it in Isaac Hamilton

Rapp’s work and thought his Colorado Supply Company Store in Morley, Colorado

to be the prefect example. Nusbaum

writes to Rapp praising his work and asks for his assistance in this endeavor,

and Rapp replies with a water color (above Fig. 3) of the building for the

November architecture exhibition.[6] Shortly after, Rapp designed the Museum

of New Mexico built in 1915, one of the earliest examples of the new Santa Fe

Style. It is easy to see Rapp is drawing

his inspiration for museum from San Esteban Mission, Acoma Pueblo. In 1920, Rapp’s Architectural firm

leaves Santa Fe paving the way for John Gaw Meem.

John Gaw Meem first arrives in Santa Fe in 1920 at the age of twenty-six. He came to the Sunmount Sanitorium, based on the suggestion of his doctor, because he had been suffering from Tuberculosis. While at Sunmount, Meem began his life long love for the southwestern sun and this truly unique city, aided by his doctor who took the patients on architectural and cultural tours of the area.[7]

His first major involvement with preservation is through the group, the Committee for the Preservation and Restoration of New Mexico Mission Churches. The group helped with repairs at Laguna, Zia, Acoma, and Santa Anna to name a few.[8] That is how he got excited about the missions and then used the vocabulary in his own designs. Meem’s decision to work with the CPRNMMC will be reflected in the rest of his architectural career. It gives him the understanding and feel of adobe, Chauvent considers this to be the wisest decision he has ever made.

His most beloved public work in Santa Fe,

according to his daughter, is the Cristo Rey Church (left Fig. 4). It is a modern adobe structure, built

in 1939 located in the Downtown and Eastside Historic District. Built in part by the Civil Conservation

Corps, a Works Projects Association group, and by the parishioners; it’s been a

model for Cornerstones Community Projects in many ways. This group works with

communities across the state to conserve public historic buildings.[9]

His most beloved public work in Santa Fe,

according to his daughter, is the Cristo Rey Church (left Fig. 4). It is a modern adobe structure, built

in 1939 located in the Downtown and Eastside Historic District. Built in part by the Civil Conservation

Corps, a Works Projects Association group, and by the parishioners; it’s been a

model for Cornerstones Community Projects in many ways. This group works with

communities across the state to conserve public historic buildings.[9]

By 1947, he is a well established architect, and it is then that he begins thinking that zoning and planning for the future is an issue if Santa Fe is to be kept the way that he thought it should—as a very unusual American city. Between 1947 and 1957 the city hires Harlem Bartholomew, a city planner from St. Louis.[10] The main danger to the downtown is the widening of the streets, because of this Meem forms a committee to write the city’s first preservation ordinance with Oliver La Farge and Irene Von Horvath.[11] After a series of negotiations with all of the city officials, a balance was struck, if Cerillos Road and the west side can develop without restrictions will it be agreed that the central part of the town and the east side will have this ordinance placed on it. That was the beginning and this year, 2007, is the fiftieth anniversary of that Ordinance.[12]

Meem’s work in preservation did not end with the Ordinance. In 1960 he helped raise $20,000 to buy the Nusbaum house on Washington St, however the effort failed and the building was demolished. In 1962, with the funds raised the city is able to found the Historic Santa Fe Foundation a nonprofit organization established by Meem to be the stewards of historic properties in Santa Fe. El Zaguan is given to them and currently holds their main offices.[13] Meem and now his daughter continue to fund the efforts of the Historic Santa Fe Foundation and Cornerstones Community Projects, nonprofits dedicated to preservation.

The

Historic Design Review Board

The Current

Ordinance, Article 14-5.2 Historic Districts Overlay, is very similar to the

original written by John Gaw Meem et al, and serves as the city’s historic administer

for the Santa Fe Style. The

stewards of the Ordinance are the Historic Design Review Board members. The seven members of the H. Board

include: Jake Barrow, Jane Farrar, Dan Featheringill,

Robert Frost, Charles Newman, Cecelia Rios,

and Deborah Shapiro. Historic

Preservation Long Range Planning Division, Section Head David Rasch, and City

Planner Marissa Barrett presided over design review meetings.

For the Downtown and Eastside Districts the Ordinance

recognizes two principle styles the Old Santa Fe Style, which is defined as

Spanish-Pueblo or Territorial, and New Santa Fe Style which is defined as

architecture that has an accord of materials, color, proportion, and overall

detail with the old style.[14] This is in direct contrast with the Secretary

of the Interior’s Standards which state, “The new work shall be differentiated

from the old.”

The Following reflects the opinions of Historic Design

Review Board members Jake Barrow and Jane Farrar, as well as Section Head David

Rasch.

Santa Fe is a certified local government, one of six or seven in the state, so it receives grant money to do inventories of buildings so their status can be upgraded to contributing if appropriate. Because it is a certified local government, David Rasch is supposedly required to follow the Security of Interior Standards. Buildings that are constructed in 2001 need to look like they are constructed in 2001, and Ordinance and H. Board state that new construction should flow seamlessly with the Santa Fe Style, because this is such a unique American city. Currently Rasch is being threatened to employ the Standards, he states that since the Ordinance predates them, that they should not apply. He also states that is not a strong argument. In his opinion, there is a way to do contemporary work that looks Santa Fe style but still sets in this century. He cites this example, of a building, not in Santa Fe but near by, that used steel for the protruding vigas. It used the vocabulary of having an exposed roof but in contemporary materials, and thus there is no confusion between what is old and what is new.[15]

Jake Barrow states, the Ordinance doesn’t reflect the Security of Interior Standards, particularly because it is based on the History of Santa Fe, and the style that John Gaw Meem and other community members were trying to preserve. It doesn’t support additions to buildings or contemporary architecture. Barrow has a little bit of a problem with this, because he has to apply the standards for his job, but when he sits on the H. Board he is really focused the Ordinance.[16]

Additions do come in and the Board does talk about the distinction; however the Ordinance pushes for less of a distinction. The Security of Interior Standards are vague and are not written in stone, it’s not prescriptive, it’s meant to allow, where as the ordinance is prescriptive. Because of this, Barrow believes that the two can exist together.[17]

Aside from the issue regarding the Security of Interior Standards, there is the problem of the city not being preservation minded, it’s much more development friendly, according to Jane Farrar and Rasch. Many of the houses are 3rd and 4th homes for people that people are not living or voting here. Plus, many of the city official’s campaigns are funded by developers that are not up to date with historic preservation. The dynamic is off and correcting it is just exhausting.[18]

Another struggle with preservation, states Farrar, is the cultural influences. This is a Spanish city and when Caucasians moved here in the mid 19th century and the country moved its manifest destiny in this direction it was not supportive of other cultures. Lurking in the background was idea that the indigenous people were not living as well as the rest of us. During her childhood, she witnessed children having their mouths washed out with soap at school, by teachers who had been brought there, because they spoke Spanish. It puts them down; it has created a sense that their culture and style of building was not great. Why would anyone want to live in a dirt house, it doesn’t have modern amenities. This caused many locals to move away, which diminished any sense of pride among the Spanish people and their legacy. Thus no one was fighting to preserve the adobe structures.[19]

The “Condo District,” as Farrar calls the Downtown and Eastside Historic District is another problem.[20] Rasch states that this is due to the Business Capital District Ordinance, which was written to keep buildings low and to help provide affordable housing in downtown Santa Fe. This created a loophole and allows for condominiums to be built because they meet the height and affordable housing requirement. It is eroding the character, says Rasch, if a street has large lots and single family homes, now with this “infill ordinance” condominiums will be built in any open lots which will take up every last square inch of the land available.[21] The H. Board doesn’t get a say in this because of the Business Capital District Ordinance, with all that money put into development, there is lot of settling and compromising, but when does the point come when everything is so compromised that nothing is left, asks Farrar?[22]

According to Farrar, it is the money that is causing the problems. The city has been so trendy, that developers see it as a money making opportunity. She had a friend equate it to mining, they come in to get the ore, take it out, and then they leave. Since the monitory value of the historic districts has grown so enormously, the city is in a lot of trouble. For example, on Alameda Street there is a modest John Gaw Meem house and seven condos have gone up around it destroying the character. The reason is an acre can sell for $500,000 to $700,000, and with the allowance of infill, developers are going to use up all the available space.

There is also the multi-billion dollar St

Francis Cathedral School (left Fig. 5) project. It is about 20 acres, and is going to be the largest

downtown development to happen at one time. It is going to break the precedent of just constructing one

house or one public building at a time.

There is not plan as of yet, there have been proposals that have been

rejected. Developers came forward

asking for height restrictions to be lifted to build tall buildings, but they

did not have the buildings designed, so that will not be allowed. When this does occur it’s going to be a

huge change for the city, the last large amount of open space will be filled in

(right Fig. 6).[23]

There is also the multi-billion dollar St

Francis Cathedral School (left Fig. 5) project. It is about 20 acres, and is going to be the largest

downtown development to happen at one time. It is going to break the precedent of just constructing one

house or one public building at a time.

There is not plan as of yet, there have been proposals that have been

rejected. Developers came forward

asking for height restrictions to be lifted to build tall buildings, but they

did not have the buildings designed, so that will not be allowed. When this does occur it’s going to be a

huge change for the city, the last large amount of open space will be filled in

(right Fig. 6).[23]

The current H. Board tends towards the conservative; some things that the board has allowed in the past would not have worked with the current board. Tension comes into play when the applicant has the option to bypass the H. Board and go to City Council, and if that happens too much, politically, that is going to be difficult for the Board, because it will lesson its authority. Some of us on the H. Board watch for that carefully, Say Barrow. If it is a marginal project they try to work with that applicant rather than just shut him or her down, especially if there is a large sum of money involved. For example, when there is a non-contributing single family house that is wanted to be torn down so four condos can be built, if the H. Board rejects it, than the applicant will go to the Council and have the decision over turned. Barrow states, he is very sympathetic to Jane’s argument.[24] However, the streetscape harmony is the strongest argument we have in this case, and making sure that is not disrupted is most important.[25]

Barrow ends, saying he makes a real effort to recognize the vernacular and the buildings that may be considered non-conforming to ensure their viability. For example, there are pitched roofs downtown and someone will propose to remove it and replace it with a flat roof—to make it look like all the other roofs. He will argue that is the exact opposite of the way Santa Fe wants to go. It shows the variety, which is essential, even though the city has strict building codes it cannot all look the same.[26]

This is such a complicated issue, should the city continue to work with an Ordinance so inflexible to new design? Both David Rasch and Jane Farrar stated that thinking is perfectly acceptable in Europe; Rasch says he would like Santa Fe to look like Tuscany where most of the architecture is yellow earthen colored walls, and green tiled roofs. Rasch would like to see more contemporary materials used that relate to the old style, but can still be distinguishable. Jane states, that the Historic District only makes up 18% of the city and that modern buildings can be built in the west side and surrounding area. She is concerned with the development and the money being forced upon the downtown, when the Ordinance was written it focused on the vernacular and the earthen building materials, now that has been replaces by multiply-million dollar homes all designed but architectural firms. This is a far cry from the city she loves and the legacy that is slowly slipping away.

Current Conservation Practices

The following

is based on an interview with Ed Crocker of Crocker Ltd. which details his

experience and common architectural conservation practices in the Southwestern

United States.

Ed Crocker’s background is in anthropology and archeology, he is a graduate of Tulane University with a degree in Mesoamerican Archeology. Has completed field work Mesoamerica and the Southwest US. He has experience in water well drilling from working with a family business as well as general construction background. While he was not fond of construction, he found he had a real affinity for old buildings and from his educational background he started looking into doing specialty types of work in historic preservation. In picking and choosing the types of jobs he wanted to do, he seemed to be ending up with the types of jobs that no one wanted to do. Mainly in stabilization of adobe built directly on the ground with no foundation, and settlement issues and structural issues that people really did not want to deal with. Many contractors were afraid of them, too much liability.

In 1986 he got a fairly large contract to

underpin the bell tower of the Santuario de Guadalupe (left Fig. 7). In the process of doing that received a

bit of recognition, including the fledgling local non-profit organization

Cornerstones Community Partnerships.

They were in the beginning of formulating a field program, to restore

the historic churches throughout New Mexico, he started volunteering and within

two years had a full time job. He

got involved with field work in preservation and the theory

In 1986 he got a fairly large contract to

underpin the bell tower of the Santuario de Guadalupe (left Fig. 7). In the process of doing that received a

bit of recognition, including the fledgling local non-profit organization

Cornerstones Community Partnerships.

They were in the beginning of formulating a field program, to restore

the historic churches throughout New Mexico, he started volunteering and within

two years had a full time job. He

got involved with field work in preservation and the theory

Adobe is one the world’s more interesting and versatile building materials. It’s ubiquitous; you can find it everywhere. It represents the oldest buildings in the world, aside from caves. There earthen buildings in Jericho that go back 9,000 years, on the river Jordan on the West Bank.

Adobe is an easy material to conserve if simple principles are followed, like keeping it dry. The problem the Southwest has faced and this is true in other parts of the world that very soon after WWII adobe began to be looked upon as a material of the poor. People started to look for ways to move out of the adobe or to cover it up with modern materials. Adobe with parapet walls (not with a pitched roof and eves) exposed to the weather does require a fair amount of maintenance. By trying to escape that maintenance people chose to cover the walls with hard plasters—cement plasters, Portland based. Obviously it was done with best of intentions, but it resulted in the retention of moisture and that lead to slow deterioration with increasing rapidness, by the mid 1980s buildings really began to start showing the signs of distress. This couldn’t be seen, because of these hard plasters. Thus, a lot of buildings were lost.

The damage was mainly slumping walls. The moisture over time would migrate to the base from whatever point it came in, whether it was the roof or plaster cracks, and it would well up at the base. If adobe retains 14% moisture by weight it will fail, it loses its capacity to hold together, it reverts to mud, so the base of wall would slump outward; this creates an affect that looks like an inverted mushroom. Meaning that the walls are coming away from the roof and it becomes very unstable. Adobe could be pushed over by hand when this happens.

Cornerstones looked at how to preserve these historic buildings that were central to the vitality of these communities. One of the first things he did to institutionalize the conservation of adobe buildings was to run training workshops in the characteristics of adobe and how can you preserve it. Most of theses centered on stripping off the hard [cement] plasters, then developing both lime and mud mortars and plasters for the exterior walls. Then institutionalizing these practices as the norm, to accomplish this through workshops, start locally and then move to nationally, now it’s become worldwide.

Over time Cornerstones came up with a whole series of techniques most of which were not new. They just reintroduced them. They had been lost during the period when adobe had lost its appeal to people. Cornerstones published an adobe conservation handbook in 1996. Now it is in its second addition, and it’s a pictorial handbook. This came from vast experience in the organization, and with hundreds of communities, gathering the information from community elders. The idea is to be very graphic and very easy to understand. Text is kept to a minimum so it can be used in any context. It has been successful in its ability to be used. It has been a tool to a lot of people.

When Crocker left cornerstones he got very heavily into structural issues. Failed soils, failed wall bases, his company started developing methods for underpinning. They solved these problems by building structural elements that they slip under the wall and then support with piers. One way to stabilize a failing wall is to through bolt “adobe cages” that are made out of steel—they are screen like and they put them on either side of the wall—and then sandwich the wall together. They can by permanent or temporary. Everything Crocker Ltd does is in the context of sound preservation principle: the smallest intervention possible with reversibility. The adobe cages can be taken off as easily as they are put on if other mediation is needed or wanted. They have also done a lot of strapping together of buildings using very easy to handle and inexpensive polypropylene straps. They have learned how to predict how buildings are going to behave under certain stress situations like earthquakes, or settlement, and moisture damage.

I asked Ed Crocker to tell me about CEB, Compressed Earthen Block, a technology used in new adobe construction.

Invented in the mid to late 70s, it derived from a Columbian/Venezuelan technique which used a mold box and a long handle and one would fill the mold box and pull the handle down and compress the soil into a block. The idea derived from that simple tool has become highly mechanized equipment. Currently contractors can load the dirt into the machine and then it is hydraulically compressed with a ram, this produces about 10 to 12 blocks a minute. The bricks come out and can immediately be stacked into walls, no drying time needed. The dirt that goes in has about 8% moisture content. This technology saves huge amounts on the cost of labor.

With adobe there are several steps in forming the blocks and then moving them to the job site. With the CEB machine you eliminate all of that and the block can me made on site.

His company promotes it for use in infill projects for neighborhoods that have a tradition in building in adobe. They have never mixed these blocks with adobe in historic buildings.

Crocker is especially worried about the

future of adobe, especially within Santa Fe. It has become more of a style then a material. The new adobe is composite. The idea is to make it modern, because

contemporary design is not allowed in the historic districts. The new adobe is a soil block

impregnated with up to 12% asphalt emulsion, laid up in a Portland cement

mortar, with concrete bond beams, sprayed with polyurethane foam, then lathed

with 16 to 20 penny nails driven right into the adobe, then plastered to

reinforce the substrate and finished with an elastomer plaster over the

top. As Crocker states, this is

not adobe (above Fig. 8).

17

Crocker is especially worried about the

future of adobe, especially within Santa Fe. It has become more of a style then a material. The new adobe is composite. The idea is to make it modern, because

contemporary design is not allowed in the historic districts. The new adobe is a soil block

impregnated with up to 12% asphalt emulsion, laid up in a Portland cement

mortar, with concrete bond beams, sprayed with polyurethane foam, then lathed

with 16 to 20 penny nails driven right into the adobe, then plastered to

reinforce the substrate and finished with an elastomer plaster over the

top. As Crocker states, this is

not adobe (above Fig. 8).

17

All the new construction in the Downtown and Eastside Historic District is being built with this new adobe. It is boring, states Crocker, to have a repeat of the same lumpy brown buildings. The Spanish Pueblo Revival and Territorial Styles does create this nice low landscape, but it lacks variety, it is tedious at the very least He would like to see contemporary buildings built in adobe in the historic district, because it advances the whole notion as a viable building material. That it is still has a place in modern architecture.[27]

Preservation Organizations

Cornerstones Community Projects is a 501(c)3 and have been since 1995. They started under another foundation, which is still exists, at the time they were called Churches Symbols of Community. The name was changed as to not be affiliated with religion—which was never its purpose, preservation of the structures is.[28]

“Established in 1986,

Cornerstones Community Partnerships assists communities in the preservation of

historic structures, promotes the use of centuries old building practices, and

supports the continuum of cultural values and heritage unique to this

region. The work is carried out in partnership with Hispanic and

Native American communities throughout New Mexico, neighboring southwestern

states, and northern Mexico. Cornerstones' community-based approach

fosters the involvement of youth, supports strong, unified communities, and

helps insure that cultural traditions and heritage are passed on to future

generations.”[29]

The following is from an Interview with the Architectural Technical Manager, Francisco UviĖa Contrers.

Cornerstones works mainly with public buildings, it does not go into private buildings. They do offer technical assistance to private home owners, says Francisco UviĖa, Conerstones will work them for a little while and then direct them to Ed Crocker, UviĖa’s Mentor.[30] However, if the house is going to be turned into a museum or the owner wants to donate it to a community then they would get involved with the process.

Most of the staff’s knowledge is in adobe architecture. That is the main architecture of the region, and also the most threatened, says UviĖa, that is what must be conserved.

Therefore Cornerstones dose not work much in town. There is so much money here [in Santa Fe] that people do not need a non-profit to help them out. Their concentration lies in many small rural communities, Indian Pueblos for example, where ever there is a need they will be there. Most of the projects in Santa Fe are educational trainings. UviĖa trains people in adobe building techniques.

When asked about the future of Santa Fe, Francisco UviĖa states simply, not good. It is becoming what he calls, “Santa Fake,” a mock-up or a movie set for tourists. It is hard to distinguish the historic adobe buildings from the ones that are not. People in preservation know from looking at the windows and the parapets, and from the size and the shape. However, people that come from the outside think that it is all adobe and it’s not.

Is there a better way for Santa Fe to be headed? According to UviĖa it might be too far gone, if you walk around Santa Fe, you might find a hand full of buildings that retain their mud or lime plasters. Being more flexible when it comes to building with the traditional materials would help. The new way of building the adobe has affected the old way, for example, building “adobe” structures with cement stucco and asphalt emollition. None of is present in traditional building and now new construction has moved so far away from it. By bringing the traditional materials back, when someone walks by a building, he or she could say; now that is adobe.

As a contrast to the ideology, of Santa Fe, UviĖa talks about one of the cities in New Mexico that he admires, Las Vegas. Situated an hour northwest of Santa Fe, about 25,000 people live there, and it has retained its flavor of architecture. It has everything, the architecture from mid 19th century, the turn of the century and even motels and the American roadside architecture from the 1950s and 60s. It’s all there and you can see the progression. There are Territorial buildings, the old adobe structures, the overlapping of the vernacular, Romanesque and the Queen Anne Victorian—it’s all there. In Santa Fe those buildings exist, but they have been covered up by stucco or painted brown. In Las Vegas all the styles shine.

The architectural progression that exists in Las Vegas has been cut off in Santa Fe, by the early proponents of the Santa Fe Style. In the early 20th Century Santa Fe sought to reverse the “Americanization” of Santa Fe, UviĖa believes that is where the city went wrong. Not because it was unimportant to preserve this unique city, but because by building everything the same it is hard for people to know what is actually historic.[31]

“The Historic Santa Fe Foundation (HSFF) is an organization that has thrived since it was founded in 1961. Our mission is to own, preserve and protect historic properties and resources of Santa Fe and its environs and to provide historic preservation education. We own eight properties in Santa Fe and holds historic Preservation easements on others.

The Historic Santa Fe Foundation is a valuable asset to our treasured community. We are here to protect what we all love about Santa Fe and to ensure that it is here for our grandchildren, and their grandchildren.”[32]

The following is from an Interview with the Executive Director, Elaine Bergman.

The foundation formed when the Nusbaum House was in danger of being torn down to build a parking lot. With the help of John Gaw Meem, $20,000 was raised to try to purchase the building, but it was too late. At the same time in the background Meem was formulating the language for this organization. While the Nusbaum house was lost, the money raised was able to begin HSFF, which now ensures the preservation of many historic structures in Santa Fe.

El Zaguan (left

Fig. 9) is one of the first acquisitions, Margretta

Dietrich, a wealthy widow who had recently resettled in Santa Fe from Nebraska,

where she had been a leading organizer  of women's suffrage

groups. She was the widow of the

former Nebraska governor. While on

a cruise in Europe when she heard the James L.

Johnson House & Garden [or El Zaguán] was going

to be torn down, she immediately had her attorney send a western union note to

buy the house, as Elaine Bergman states, this is an early example of

preservation.

of women's suffrage

groups. She was the widow of the

former Nebraska governor. While on

a cruise in Europe when she heard the James L.

Johnson House & Garden [or El Zaguán] was going

to be torn down, she immediately had her attorney send a western union note to

buy the house, as Elaine Bergman states, this is an early example of

preservation.

With the help of Dorothy

Stewart, Dietrich’s sister and an artist, they converted the house into

apartments, and Stewart built what she called the galleria on the east

end. The apartments were soon

rented filled to artists. This

began in the 1920s, and HSFF still carries on the tradition of renting to

artists. Dietrich died in 1961 and a group of investor purchased it, including

Meem. Twenty years later they donated it to HSFF (right, artistic detailing Fig.

10).

With the help of Dorothy

Stewart, Dietrich’s sister and an artist, they converted the house into

apartments, and Stewart built what she called the galleria on the east

end. The apartments were soon

rented filled to artists. This

began in the 1920s, and HSFF still carries on the tradition of renting to

artists. Dietrich died in 1961 and a group of investor purchased it, including

Meem. Twenty years later they donated it to HSFF (right, artistic detailing Fig.

10).

Currently the

foundation owns eight buildings; they were selected based on their

vulnerability to being demolished. Some of their properties included: The

Felipe B. Delgado House, The Oliver P. Hovey House, and The Donaciano Vigil

House. The Delgado House is now a

bank, the Hovey House is an art gallery and the Vigil House remains a private

residence. By owning and renting

eight properties the foundation is able to help sustain itself.

The leases to these structures are extraordinary, renters can’t make

changes. They see their tenants as stewards for the buildings. In terms of the three private

residences they have to not mind a little loss of privacy, if HSFF has special

guests or tours. The benefit is

renters pay about half market rate.

It is extremely competitive to rent one of these buildings, and

currently, Bergman states, they have wonderful tenants.

The foundation is always working on many different projects.

Currently education is at the forefront.

Helping people maintain their historic properties and therefore

acquiring new easements. They also

run earthen materials workshops, again to help people with their

buildings. One of the most popular

workshops focuses on how to mix mud plasters, how to apply them and what kind

of substrate is needed. Bergman

jests, that the popularity is because it lets people get their hands muddy.

One of the most important elements of their education program is

the preservation trades internship.

One of the biggest challenges in historic preservation is that designers

and trades people are losing the ability to work with earthen materials. This internship is designed to help

remedy that problem.

Presently the HSFF is not looking to acquire any more

structures, and is focusing more on easements to help preserve the cities

historic treasures. They have to be realistic about acquisition, they already

carry two mortgages, one is for the property next door and that was

purchased as a strategy to limit development. El Zaguán and the Donaciano

Vigil house are gifts to the foundation; the other six properties were

bought. They acquired the Hovey

House downtown through mortgages, because it was extremely threatened, as were

the other five properties.

Bergman ends with what she loves most about Santa Fe what she

does. It is the little details,

the natural environment, the city in the valley between the two mountain

ranges,

The Future of Santa Fe

The general consensus is the future of Santa Fe does not look good,

whether one is for or against new construction in the Historic Districts. The Following are quotations from four

of the seven interviews:

Right now the future doesn’t look good; we have a rather non supportive city council. Economic development is very big, green architecture is very big. A lot of people who do not understand historic preservation think that it is anti-green, which it’s not.

-David Rasch

It is scary, it is very scary. I think because tourism is our major industry it behooves the city to [preserve] it no matter how much it hurts [economically].

-Nancy Wirth

When you go downtown and walk up Canyon Road—it’s really trinkified. Even the art that is very pricey it is still kitsch. The community has moved away from the downtown.

-Jake Barrow

I’m just really curious at this point. It’s a race—we have global warming, corporate greed all these things and they all affect each other…you just don’t know. I do not know what the private community is anymore. For years it was not an expensive or accessible city. The charm drew artists that could work in a restaurant while they wrote their book or made their art. It has really lost that.

-Jane Farrar

The city is becoming more and more touristy, which in a way is good, as Nancy Wirth says, it is the city’s main industry. However, one must be careful with a small town that the industry doesn’t take it over before there is nothing left, as Jane Farrar worries about. There needs to be more of a bridge between developers and preservations. One that does not involve a compromise that is one sided. Developers must realize that in order for Santa Fe to be the valuable commodity that it is, it must retain some of its historic character. If it becomes too over developed the tourists industry will eventually die. It is also important for building practices to move forward, what may have been viable in the past may not be the best course for the future.

How could developers and preservationists work together? It is an odd concept, but not impossible. During the graduate course HP 304 entitled Contemporary Preservation Policy and Planning Seminar, professionals from the state of Vermont discuss current policies. Paul Bruhn, the executive director of Preservation Trust of Vermont, came to speak on February 27, 2007. One of the components of the Preservation Trust of Vermont is downtown revitalization. How does one make small businesses viable in the age of Wal-Mart®? The answer is to work together. Bruhn shared a plan to incorporate a Wal-Mart® into downtown St. Albans, VT. It would be smaller than most of their stores, non-obtrusive in design, and parking would be located underground. The idea is it would bring people downtown and if consumers could not find what they were looking for at Wal-Mart®, then there would be numerous specialty stores to choose from. If this does not happen and Wal-Mart® builds a store outside the downtown, it will draw all the business with it. In this case, Burhn and the Preservation Trust of Vermont are hoping to create a beneficial situation for both parties. This is a very site specific endeavourer, but it is this kind of creative thinking that promotes a healthy relationship between preservation and development.[34]

How could Santa Fe be more flexible without compromising its character? Currently the Ordinance only allows for new construction in the Spanish Pueblo Revival and the Territorial Revival Style. A step forward, and a suggestion of both Ed Crocker and Francisco UviĖa, could be to allow contemporary design, but put the restraint that it must be built out of traditional earthen materials. With this restraint the color of the southwest and the height restrictions can be applied. However, it will allow for variety as well as reviving the use of the material which is so important to this region.

While the issue of preservation is unsolved, there are still many events and developments that are for preservation both structurally and culturally:

The city does make an effort, it has large music program downtown, there is Indian Market at the Palace of Governors, and the Spanish Market. The mayor has a new initiative to make Santa Fe a green city. There are still many artists and young artists too. The city tries to encourage that, making studio space cheap. Many aspects that made Santa Fe great still exist here.

-Jake Barrow

The Railyard Project is a positive direction for Santa Fe. Located in the Transition Historic District, it used to be a complex of warehouses. The project includes a larger area of open space that is now going to be a park. It’s going to be great, states Nancy Wirth. There will be museums and new galleries, including Santa Fe Clay, as well as a Hispanic Cultural Center, and one of the major components is going to be a large year- round farmers’ market. It will be a major component to the downtown and will keep businesses from moving out towards the malls.[35]

It behooves the city to look at the Ordinance critically—where is it succeeding and what needs improvement. As Farrar says, when it was written it really focused on preserving the vernacular and the earthen traditions within the Santa Fe Style. However, in the last fifty years that has translated to multiple condominium developments and large 3,000 to 4,000 square foot mansions build out of modern adobe, as Crocker and UviĖa explain. This is not the intent of the early preservationists, and it is certainly not where current preservationists want the city to go. In conclusion, Francisco UviĖa states, “People love Santa Fe and I love Santa Fe, but it’s a battle.” There is not better way to describe it.

Appendix A

Photographs Noted in Text

Figure 1 Acoma Mission, photo about 1935 from The Myth of Santa Fe, Chris Wilson.

Figure 2 Taos Pueblo, North building, photo about 1880 from The Myth of Santa Fe, Chris Wilson.

Figure 3 Colorado Supply Company, water color Isaac Hamilton Rapp from The Creator of the Santa Fe Style, Carl D. Sheppard.

Figure 4 Cristo Rey Church, Sara Casten

Figure 5 Francis Cathedral School, Sara Casten

Figure 6 Francis Cathedral School parking lot, Sara Casten

Figure 7 Santuario de Guadalupe, Sara Casten

Figure 8 Modern Adobe Structures, Sara Casten

Figure 9 El Zaguan, Sara Casten

Figure 10 El Zaguan detail, Sara Casten