North Carolina

Number

of Victims

The total number of

victims sterilized

in North Carolina was over 7600 (Winston-Salem,

“Lifting the Curtain on a

Shameful Era”). Of

this number, females

represented approx. 85% of those sterilized, while men only represented

15% (State

Library, “Statistics,” p. 1).

By the later

1960s, the sterilization of men was virtually halted as women made up

99% of

those sterilized (Sinderbrand, p. 1). Blacks represent

39% of those

sterilized overall. But

by the later

1960s, blacks made up 60% of those sterilized, even though they were

only a

quarter of the population (Sinderbrand, p. 1). Of those

sterilized up to

1963, 25% were considered mentally ill and 70% were mentally

deficient. In each

of these categories,

females account for over 75% of the sterilizations. Of all the

states, North

Carolina ranked third in the United States for number of people

sterilized.

Sterilizations started

in 1929 with the

passage of the sterilization law and continued through 1973, when the

last

recorded sterilization is known to have occurred.

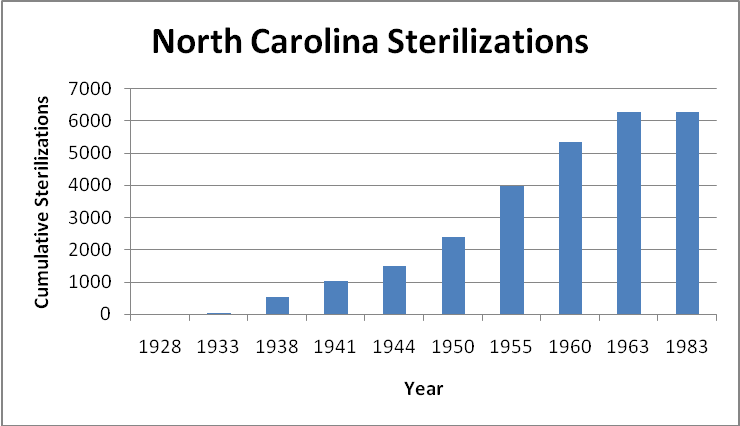

After the passage of the sterilization law in 1929, sterilization law began at fairly slow rate. It was not until about 1938 that sterilizations began to increase at a steady rate. After WWII, sterilizations accelerated and peaked in the two years between 1950 and 1952, with 704 sterilizations (State Library, “Statistics”, p. 1). This makes North Carolina unique, as its peak sterilizations occurred after WWII when most other states had ceased performing operations. After 1960, the rate of sterilization began to slow and continued to decrease from a rate of about 250 a year in 1963 to 6 per year in 1973. From 1950-1963 there were an average of about 300 sterilizations per year. In the peak years (the 1950s) there were about 7 sterilizations for every 100,000 residents of the state per year.

Passage of Laws

The very first sterilization

law was

passed in 1919 but to our knowledge it was never used. Many

feared that the law was unconstitutional

and therefore the state feared putting it into practice (Paul,

p.420). But then in 1929, The North Carolina General

Assembly passed its true sterilization law stating, “the governing body

or

responsible head of any penal or charitable institution supported

wholly or in

part by the State of North Carolina, or any sub-division thereof, is

hereby

authorized and directed to have the necessary operation for

asexualization or

sterilization performed upon any mentally defective or feeble-minded

inmate of

patient thereof” (State Library, “History”, p. 1). It also

stated that the operation had to be

in the best interest of the mental, moral or physical improvement of

the

individual, or for the public good. In

1933, North Carolina enacted the sterilization law that remained for

the rest

of the eugenics movement there. This law

“provided for notice, hearing, and the right to appeal” (Paul, p.

421). The passage of this law also created the

North Carolina Eugenics Board, which will be discussed in a later

section. The passage of the 1929 sterilization law

made North Carolina the 17th state out off 33 to pass one.

This

law remained effective until 1973, when the last

recorded sterilizations were performed (State

Library, “History,” p. 1).

Finally,

on April 4, 2003, the North Carolina Senate voted

unanimously to overturn the 74-year-old eugenics law (“Bill to Overturn

Eugenics Law Passes State Senate,” p. 1).

Groups

Identified by the Law

As stated

in the original sterilization

law of 1929, the groups targeted for sterilization were identified as

“mentally

ill, mentally retarded, and epileptic” (Paul, p. 421).

However, the law also stated that the purpose

of sterilization is to protect impaired people from parenthood who

would become

seriously handicapped if they were to assume parental responsibilities

(Paul,

p. 421).

Process of

the Law

Under the

sterilization law, the North

Carolina General Assembly gave the governing body or executive head of

any

penal or charitable public institution the authority to order

sterilization of

any patient or inmate whose operation they considered would be in the

best

interest of the individual and of the public good.

It also gave the county boards of

commissioners authority to order sterilization at the public’s expense

of any

“mentally defective or feeble-minded resident upon receiving a petition

from

the individual’s next of kin or legal guardian” (State Library,

“History”, p. 1).

All

the orders for sterilization had to be reviewed and approved by the

commissioner of the Board of Charities and Public Welfare, the

secretary of the

State Board of Health, and the chief medical officers of any two state

institutions for the feeble-minded or insane.

In the reviewing process, they looked at a medical and

family history of

the individual being ordered for sterilizations to help decide whether

the

operation would be performed or not.

They also considered whether it was “likely that the

individual might

produce children with mental or physical problems” (State Library,

“History”,

p. 1).

In 1933,

under the new law, the General

Assembly created the Eugenics Board of North Carolina to review all

orders for

sterilization of “mentally diseased, feeble-minded, or epileptic

patients,

inmates, or non-institutionalized individuals” (State Library,

“History”, p. 1). This

centralized board included five members:

the commissioner of the Board of Charities and Public Welfare, the

secretary of

the State Board of Health, the chief medical officer of a state

institution for

the feeble-minded or insane, the chief medical officer of the State

Hospital at

Raleigh, and the attorney general. In the hearings

of patients or inmates in

a public institution, the head of that institution was the prosecutor

in

presenting the case to the Eugenics Board.

In hearings of individuals who were non-institutionalized,

the county

superintendent of welfare or another authorized county official acted

as the

prosecutor. However,

in both hearings,

the prosecutor provided the board with a medical history signed by a

physician

familiar with the individual’s case. The petition for the hearing was

sent to

the individual being ordered or to their next of kin or legal guardian. In the situation where

this person could not

represent or defend themselves at the hearing, the next of kin,

guardian, or

county solicitor stepped in to represent them.

If the board decided to order the sterilization, the order

had to be

signed by at least 3 members and then returned to the prosecutor. This decision could be

appealed by the

individual to the county superior court and then further appealed to

the state

supreme court. If

the appeal was

successful, any petitions for sterilization were prohibited for one

year,

unless the individual, or his or her guardian or next of know requested

sterilization (State Library, “History”, p. 1).

Precipitating

Factors and Processes

Eugenics

in the 1950s was largely a

southern movement, as most other states were weaning off from

sterilization. Very

little sterilization

occurred in the 1930s in North Carolina (and in the other southern

states)

because the Great Depression resulted in funding crises that didn’t

allow for

sterilization to occur in full force in the south.

Therefore, sterilization picked up pace after

WWII, especially during the mid-1950s (Castles, p. 1).

One factor

leading to the acceleration

after WWII was the race issue.

Race has

always been a very loaded issue in the south, as slavery was prominent

there. When slavery

was legal, white

slave owners encouraged the reproduction of their slaves in order to

create

bodies to work and sell. However,

this

changed in the 1950s when slavery was abolished and the civil rights

movement

was gaining speed. By

the 1950s, some

white people were becoming anxious about supporting blacks through

welfare. The heads

of the agencies of

welfare departments agreed on the value of sterilization for reducing

general

welfare relief and ADC (Aid for Dependent Children) payments

(Winston-Salem, “Wicked

Silence”). The

state believed that blacks

accounted for the majority of illegitimate births that were

“subsidized” by

ADC. The state

threatened to remove

welfare benefits if they person did not submit to the operation. The

fears about the rising cost of the ADC program was the major factor in

leading

to the shift in racial composition of those targeted for sterilization. As the attention shifted

away from the

structural causes of poverty and crime to placing the blame for urban

poverty

and social unrest on blacks, sterilization of blacks was easily

facilitated

(Schoen). It became

necessary to control

the reproduction of ADC recipients, as a result, the percentage of

blacks

sterilized rose from 23% in the 1930s and 1940s to 59% between 1958-60

and

finally to 64% between 1964 and 1966 (Schoen, p. 108).

Sterilization

also accelerated because

it expanded to include the general population when the state gave

social

workers the authority to submit petitions for sterilization. Therefore, the amount of

eligible people

increased drastically. “The

North

Carolina Board-which initially targeted those who were deemed mentally

ill-

expanded its program to include the general population.

In fact, “the majority of those sterilized

had never been institutionalized, and 2,000 were younger than 19”

(Wiggins, p. 1). In

addition, the fight against poverty in

North Carolina led to sterilizations in the general population. As this fight intensified,

a new policy was

created that led to an increase in the number of non-institutionalized

people

who were sterilized. Sterilizations

of

the non-institutionalized rose from 23% between 1937 and 1951 to 76%

between

1952 and 1966 (Schoen, p. 109).

Groups

Targeted and Victimized

Women,

including wives, daughters,

sisters and unwed mothers, were largely overrepresented. They were labeled as

either “promiscuous,

lazy, or unfit” (Wiggins, p. 1), or more commonly, as “sexually

uncontrollable”

(Schoen, p. 110). Overall,

women made up

84.8% of sterilizations (State Library, “Statistics”, p. 1). However, more interesting

is that the

sterilization of men virtually halted in the 1960s, with only 2

sterilizations

in 1964, and 254 sterilizations of women (State Library,

“Sterilizations”, p. 1). Therefore,

after 1960, women accounted for

99% of sterilizations (Sinderbrand, p. 1). While many white

women were sterilized,

the state began to focus on sterilizing black women as they became the

majority

of the welfare population. Black

women

were seen as highly uneducated, poor, and as having higher fertility

rates than

their white female counterparts. As

the

amount of black women on welfare increased, “the public association

between ADC

and black female recipients was particularly close” (Schoen,

p. 109). Black

women were presumed to have

uncontrollable sexual behavior, and as these racial stereotypes were

reinforced, black women became an even larger target for controlled

reproduction through sterilization.

Social

class also played a role in who

was targeted after WWII, as women on welfare, usually living in

socially

isolated places, were overrepresented.

The reason for this was to prevent “poor” and “unfit”

women from

reproducing children with mental or social ills (Wiggins, p. 1). They were generally

ordered for sterilization

by social workers and lived outside of institutions.

The poor were not only targeted for their

“social ills” but also because they were easier to sterilize. They would often not be

released until they

or a family member agreed to have them sterilized (Wiggins, p. 1).

Finally, race also played a role in those

targeted for sterilization. During

the Civil Rights Movement, petitions

were sent to the state’s eugenics board for black women (Winston-Salem,

“Wicked

Silence”). Overall,

by the later 1960s,

60% of those sterilized were young, black women (Wiggins, p. 1). Overall, blacks represent

38.9% of

sterilizations. This

is because

sterilizations of blacks were concentrated in a shorter period of time

and because

minorities only made up quarter of North Carolina’s population (State

Library,

“Statistics”, p. 1). From

the years 1960

to 1962, of the 467 sterilization ordered by the board, 284 (61%) were

black

(Winston-Salem, “Wicked Silence”).

In

addition, blacks were targeted because the amount of welfare recipients

who

were black grew from 31% in 1950 to 48% in 1961 (Schoen, p. 109). It was seen as necessary

to sterilize those

recipients of welfare to decrease the growing financial burden on the

state.

There are

two stories that were made

public by two black women who were sterilized against their will at a

young age

in North Carolina. The

first is Elaine

Riddick, who had been sterilized at the age of 14 by a state order in

North

Carolina in 1968 after giving birth to a baby after being raped. When she was operated on

she was not informed

that she was being sterilized. She

only

discovered this years later when she was trying to get pregnant with

her

husband. She was

part of the lower class

and the consent form had been signed by her illiterate grandmother and

neglectful father. She

blames the

sterilization for ending her marriage and is still affected by the

surgery,

saying, “I felt like I was nothing.

It’s

like, the people that did this; they took my spirit away from me”

(Sinderbrand,

p. 1).

The second

story is of Nial Cox

Ramirez, who was sterilized at the age of 17 after several instances of

pressure from social workers to get sterilized after becoming pregnant. She eventually complied

because they

threatened to take her family off of welfare, but she was never

informed of the

consequences of the surgery. She

was

assured she would be able to become pregnant again, but learned

otherwise when

she attempted to conceive years later.

Like Riddick, her marriage fell apart.

When she sued the state of North Carolina in 1967, it was

dismissed as a

technicality (Wiggins, p. 1). These

women were only 2 of those who fell under the categories of the groups

targeted, and suffered as a result.

Other

Restrictions Placed on Those Identified in the Law or

with Disabilities in General

There are

no other

known restrictions placed on those identified in the law.

Major

Proponents

Dr.

William Allan was North Carolina’s

initial promoter of negative eugenics.

He wrote his first study on eugenics in 1916 and by the

end of his life

he had written 93 papers. He

had his own

private practice until 1941, when he started the medical genetics

department at

Bowman Gray. He

thought that hereditary

diseases could be halted by prevention and based much of his work on

field

studies and surveys. He

pushed for a

statewide bank of genetic information that would catalog peoples’

genetic

backgrounds to see if they were prospective parents.

He continued to push for this until his death

in 1943 (Winston-Salem, “Forsyth in the Forefront”).

. (Photo

origin: Winston Salem Journal, Against Their Will,

available at

http://media.gatewaync.com/wsj/photos/specialreports/againsttheirwill/graphics/parttwo_herndonsmall.jpg)

. (Photo

origin: Winston Salem Journal, Against Their Will,

available at

http://media.gatewaync.com/wsj/photos/specialreports/againsttheirwill/graphics/parttwo_herndonsmall.jpg)

Dr. C.

Nash Herndon followed in the

footsteps of Allan when he took over the department at Bowman Gray

after his

death. He conducted

surveys of those

with disabilities in an effort to find links of hereditary diseases. He was president of the

American Eugenics

Society from 1953-1955 and president of the Human Betterment League of

North

Carolina. He was

the greatest

contributor in pushing the eugenics movement forward in North Carolina

after

WWII (Winston-Salem, “Forsyth in the Forefront”).

James G.

Hanes was the founder of the

Human Betterment League of North Carolina in 1947.

The league changed the face of eugenics in

North Carolina by giving the board new legitimacy.

In 1957, the league had sent out more than

575,000 pieces of mail promoting the sterilization program and helped

lead to

the increasing number of sterilizations on blacks and women outside of

institutions in the following years (Winston-Salem, “Selling a

Solution”).

“Feeder

Institutions” and institutions where sterilizations were

performed

(Photo

origin: Winston Salem Journal, Against Their Will,

available at

http://media.gatewaync.com/wsj/photos/specialreports/againsttheirwill/graphics/parttwo_bowman.jpg)

(Photo

origin: Winston Salem Journal, Against Their Will,

available at

http://media.gatewaync.com/wsj/photos/specialreports/againsttheirwill/graphics/parttwo_bowman.jpg)

The Bowman Gray School of Medicine housed a program for eugenic sterilizations starting in 1948. It was aimed at the eugenic improvement of the population of Forsyth County. It consisted of a systematic approach that would eliminate certain “genetically unfit strains from the local population” (Winston-Salem, “Forsyth in the Forefront”). It expanded the program throughout North Carolina. The school received much philanthropic support for research of genetic ideas. Today, school officials condemn eugenic research, as the dean of the school, Dr. William B. Applegate, states “I think that the concepts and the practice of eugenics is wrong and unethical and would in no way be approved or condoned in modern medical times” (Winston-Salem, “Forsyth in the Forefront”). The school is now part of the Wake Forest University Baptist Medical Center-one of the most respected academic medical centers in the country. Although officials of the school condemn eugenics there is no mention of the program for eugenic sterilizations on the medical center’s website.

(Photo origin: North Carolina Department of Health and Human

Services, available at

http://www.dhhs.state.nc.us/mhfacilities/images/Caswell-Center.jpg)

(Photo origin: North Carolina Department of Health and Human

Services, available at

http://www.dhhs.state.nc.us/mhfacilities/images/Caswell-Center.jpg)

The

Stonewall Jackson Training School

was founded in 1907 and was North Carolina’s first juvenile detention

facility. This was

mostly a school for

boys, but a few girls were sterilized there over its history, all of

whom were

labeled as “mentally retarded”. The

boys

who were sent there had only “minor scrapes” with authorities, not for

mental

illness. In 1948,

seven boys out of 300

were targeted for sterilization because they were ready for discharge. These boys were deemed

“feebleminded” as a

justification for the operation. These

were the only boys sterilized at this school (Winston-Salem, DETOUR:

In ’48

State Singled out Delinquent Boys).

The

building still exists but does not remain in operation today. There is no commemoration

at the sight or

mention of the past.

The

Goldsboro Training School, also

known as the O’Berry Center, it opened in 1957 as the first institution

for

black mentally retarded citizens.

It had

150 clients were transferred to it from Cherry Hospital, at which point

the

treatment of the patients was limited to academics and vocational

training. It is

still operating today with

approximately 430 clients, but it is no longer limited to blacks

(Castles, pp. 12-14). The

center’s website refers to the institution's history

of dealing with Black mentally retarded citizens.

Opposition

Blacks

were opposed to sterilizations one two levels: those who

knew about its racial bias and those who didn’t.

The sterilization program was only whispered

about in the black communities, and any evidence that race played a

part in those

who were sterilized wasn’t made public or scrutinized.

Therefore, the eugenics board was allowed to

proceed with few hurdles (Winston-Salem).

Those blacks knew about the racial bias involved with

sterilization tried

to push for their rights. In

1959, State

Senator Jolly introduced a bill that would authorize the sterilization

of an

unmarried woman who gave birth for the third time.

This bill was contested by group of

blacks. However, the senator's response was

"You should be

concerned about this bill. One out of four of your race in

illegitimate".

Blacks that demanded to be heard were ruled out of order by

the

white-controlled legislature (Winston-Salem, "Wicked Silence").

Many

college students were also in opposition to the

sterilizations. In

1960, students

from N.C. A&T State University began

sit-in movement against

states progressive attitude or race relations.

However, this gained little speed or recognition by the

state to make

any changes. Also,

at Shaw University in

Raleigh from 1968 to 1972, student activists tried to educate blacks

about the

issues and threats of sterilization.

However, they lacked detail of the issues, and therefore

this gained

little momentum as well (Winston-Salem, “Wicked Silence”).

Today,

North Carolina is trying to amend for its past, making it one

of the only states to do so thus far.

In

April 2003, the sterilization law was unanimously voted to be

overturned by the

North Carolina Senate. A

few weeks

later, a law was then signed by Governor Easley to officially put an

end to

forced sterilizations in North Carolina.

Soon after, on April 17, 2003, Easley issued a public

apology, stating, “To

the victims and families of this regrettable episode in North

Carolina's past,

I extend my sincere apologies and want to assure them that we will not

forget what

they have endured" ("Easley Signs Law Ending State’s Eugenics

Era," p. 1). Then,

in December

2005, the National Black Caucus of State Legislators passed resolution

calling

for federal and state programs to identify victims nationwide and get

them health

care and counseling (Sinderbrand, p. 1).

However, these current efforts to find sterilized victims

are difficult

due to budget constraints and high costs of a publicity

campaign.

Therefore, efforts to find victims through "free media" is being

employed, such as posting info on bulletins, offices, health

departments,

libraries, schools, billboards, and city buses etc. (Sinderbrand, p. 1).

Bibliography

Castles,

Katherine. 2002. "Quiet

Eugenics: Sterilization in North Carolina's Institutions for the

Mentally

Retarded, 1945-1965." Journal of Southern History

68: 849-78.

Noll,

Steven. 1995.

Feeble-Minded in Our Midst: Institutions for the

Mentally Retarded in the South, 1900-1940.

Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

Paul, Julius. 1965. “Three Generations of Imbeciles are Enough: State Eugenic Sterilization Laws in American Thought and Practice.” Washington, D.C.: Walter Reed Army Institute of Research.

Reynolds,

Dave. 2003a. "Bill To

Overturn Eugenics Law Passes State Senate." Inclusion

Daily Express: International Disability Rights News

Services (April 4).

Reynolds,

Dave. 2003b. "Easley

Signs Law Ending State’s Eugenics Era." Inclusion

Daily Express: International Disability Rights News

Services (April 17).

Schoen,

Johanna. 2005. Choice and

Coercion: Birth Control, Sterilization, and Abortion in Public Health

and

Welfare. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

Sinderbrand,

Rebecca. 2005. "A

Shameful Little Secret." Newsweek 33 (March 28).

State

Library of North Carolina.

"Eugenics in North Carolina." Available at < http://statelibrary.dcr.state.nc.us/dimp/digital/eugenics/index.html. >

Wiggins,

Lori. 2005. “North Carolina

Regrets Sterilization Program.” Crisis 112, 3: 10.

Winston-Salem

Journal. Against Their

Will. Available at <http://againsttheirwill.journalnow.com/>.