Colorado

Number of Victims

There were no legal sterilizations recorded in

Passage of law(s)

No laws were passed that legalized compulsory sterilizations

although there were four attempts made in 1908, 1913, 1925, and 1928 (Prince). There was, however, a 1922 case in which a

Colorado judge attempted to force a woman to choose between having her children

sent to a state institution or to submit herself to being sterilized (Paul, p. 574). The results of this case are unknown (Paul,

p. 575). In the 1990s a case reached the

Colorado Supreme Court in which they tried to determine whether a woman had the

mental capacity to decide for herself if she should be sterilized (in order to

avoid the risks to her health that her Diabetes would increase upon becoming

pregnant) (Field and Sanchez, p. 55).

The court ruled that she was mentally incompetent and therefore made the

decision for her that she should be sterilized although she expressly stated

that she wished to retain reproductive capabilities (Field and Sanchez, p. 56). This

ruling was preceded by a similar case in

New Jersey which ruled in favor of the parents in their request to have

their

daughter with Down syndrome sterilized because they judged it to be in

her best

interests (Reilly, p. 167).

Although no laws were passed, "According to the testimony of a later superintendent at the Colorado State Hospital, sterilization had long been a ‘routine operation’ for many patients, a procedure that could be administered at the superintendent’s discretion" (Bruinius, p. 328). Sterilization laws (with eugenic leanings) are still a concern today. A Colorado legislative committee accepted a bill in the 1990's meant "to assist in reducing the crime rate." If the bill had passed, it would have required "family planning incentives" to be introduced by the Colorado Department of Corrections. However, the bill died because of serious scrutiny from the press (Lombardo, p. 275).

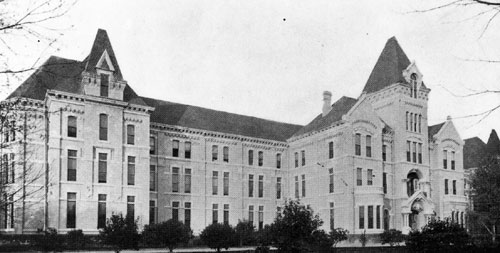

(Photo origin: Colorado State Hospital, available at http://www.asylumprojects.org/index.php?title=Colorado_State_Hospital)

(Photo origin: Colorado State Hospital, available at http://www.asylumprojects.org/index.php?title=Colorado_State_Hospital)

Groups identified in the (Proposed) Law

The groups identified in the proposed bills were the “insane” (Paul, p. 576).

Precipitating factors and processes

Although no law was passed, the eugenics movement was very alive in Colorado as demonstrated by the fact that several attempts were made to legalize compulsory sterilization of the “hereditarily unfit” (Paul, p. 575). The movement was especially focused around the Colorado Medical Society which churned out eugenic propaganda, ran a eugenic journal, and lobbied intensely for legislation (Prince, p. 2). Another strong factor in the popularity of eugenic ideas were the Colorado Women’s Clubs which were already seen as very progressive because Colorado was the first official state to grant suffrage to its women. These woman spearheaded events such as eugenic baby shows in order to persuade the people of Colorado that hereditary fitness was essential to the success of the human race (Prince).

Groups targeted and victimized

When attempts at passing legislature to sterilize the insane failed, those in poverty became targets of eugenic prejudices (Paul, p. 576). Those who were victimized were specifically poor mothers who relied on public assistance from the state to raise their children (Paul, p. 574). A woman named Lucille was “sterilized against her will by the state of Colorado” at the Colorado State Hospital in 1941 at the age of seventeen (Bruinius, p. 324). She was said to be feebleminded, mentally deficient, and incorrigible. Lucille sued Frank Zimmerman, the superintendent at the Colorado State Hospital at that time, and three other doctors who helped with her sterilization process. The case became quite famous locally. Lucille lost her case because of a technicality. She did not make a claim before the statute of limitations was up. She claimed that she was not able to do it previously because of her mental state, but the defense convinced the jury otherwise. The doctors who had illegally sterilized Lucille were acquitted on November 4, 1958 (Bruinius, p. 354).

Other restrictions placed on those identified in the law or with disabilities in general

It was illegal to use contraceptives which made it difficult to avoid pregnancy. This lack of birth control increased the chances of a woman who was unable to fiscally support her family, of having more children (Paul, p.574). Colorado still has strict marriage restriction laws that prohibit marriages between people “lacking the capacity due to mental infirmity (…) or inability to consummate”, although it does permit marriages between first cousins (Jrank.org).

Major proponents

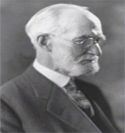

(Photo origin: Pueblo Community College; available at http://www.pueblocc.edu/AboutUs/Foundation/AnnualFundraiser/1992_Inductees.htm)

(Photo origin: Pueblo Community College; available at http://www.pueblocc.edu/AboutUs/Foundation/AnnualFundraiser/1992_Inductees.htm)

The best-known advocate of eugenic policies in the state of

Colorado was Richard Corwin (Prince). He

was the director of the Colorado Coal and Iron Company’s industrial health

clinic in

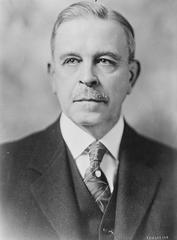

(Photo origin: Dr. Hubert Work, available at http://ookaboo.com/o/pictures/topic/2507269/Hubert_Work)

(Photo origin: Dr. Hubert Work, available at http://ookaboo.com/o/pictures/topic/2507269/Hubert_Work)

Dr. Hubert Work was the founder of the Colorado State Hospital (1896). Dr. Work was a believer in eugenics and thought something had to be done to cure the “social curse” of feeblemindedness. He thought that mental weaknesses should be eradicated instead of just treated. He was elected to the presidency of the American Medico-Psychological Association in 1912 (now known as the American Psychological Association). Dr. Work stated that “there are but two remedies for this social pollution: The segregation of the abnormal at puberty by holding them in institutions during their procreative period, or rendering them sterile,” while also saying that the first remedy was a failure and that “We are then perforce compelled to invoke the alternative of sterilization.” He became the chairman of the Colorado Republican Party in 1912. In 1921, President Warren G. Harding appointed him to the position of Postmaster General and after that he was appointed as Secretary of the Interior. He became chairman of the National Republican Committee in 1928. He used these prestigious positions to advocate for his eugenic beliefs (Bruinius, pp. 325-329).

Dr. Minnie C.T. Love was a founder of the State Industrial School for Girls at Morrison, the founder of the Florence Crittenton Home for troubled girls, an organizer of the State Industrial School for Girls, a member of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, and she helped found the Denver Women’s Club. She started her own private practice in Washington prior to moving to Colorado where she was appointed as head of the Colorado Board of Health. Love was also elected to the Colorado State Legislature. She became an “Excellent Commander of the Ku Klux Klan. Dr. Love was a firm eugenics reform advocate. She sponsored a bill in 1925 to sterilize Colorado’s “unfit citizens,” but her bill was effortlessly beaten (Bruinius, pp. 332-336).

Dr.

Frank Zimmerman was the superintendent of the Colorado State

Hospital. He consistently searched for loopholes in the

legislation that would allow him to sterilize people in the name of

eugenics. Zimmerman actively lobbied for the passage of a bill

“to sterilize feebleminded and epileptic individuals” in 1929, but the

bill did not pass (Bruinius, pp. 338-341).

Opposition

The magazine Law Notes

expressed a concrete disapproval of the court case in which a mother was forced

to make the “cruel decision” of either giving up her children or of allowing

herself to be sterilized. The editors of

this publishing argued that it was illogical to prevent the dissemination of

contraceptive information and then punitively punish those who have children

and need aid from the state (Paul, p. 575).

The strongest force of opposition came from the Catholic circles of

Bibliography

Field,

Martha A., and Valerie A. Sanchez. 2001. Equal Treatment for People with

Mental Retardation: Having and Raising Children.

JRank.org. “Annulment and Prohibited Marriage laws - Information on the law about Annulment and Prohibited Marriage - Prohibited Marriage.” Available at <http://law.jrank.org/pages/11834/Annulment-Prohibited-Marriage-Prohibited-Marriage.html">

Lombardo, Paul A. 2008. Three Generations, No Imbeciles. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Paul,

Julius. 1965. “‘Three Generations of Imbeciles Are Enough': State Eugenic

Sterilization Laws in American Thought and Practice.” Unpublished manuscript.

Prince, Rob. 1999. “Colorado's Secret Scalpel Page.” (November 24). Available at <http://clem.mscd.edu/~princer/ant440b/article_scalpel.htm>.

Pueblo

Community College. “Pueblo Hall of Fame: 1992 Inductees.” Available at

<http://www.pueblocc.edu/AboutUs/Foundation/AnnualFundraiser/1992_Inductees.htm>.

Reilly, Phillip R. 1987. “Involuntary Sterilization in the United States: A Surgical Solution.” The Quarterly Review of Biology 62: 153-70.

Reynolds, Dave. 2003. “The Eugenic Apologies.” Ragged Edge Online (November/December). Available at <http://www.ragged-edge-mag.com/1103/1103ft1.html>.