(Backhouse, pl. iv)

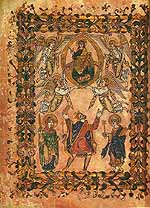

"The new regime [to change the New Minster, Westminster, into a Benedictine monastery] was solemnly confirmed by this document, dated 966, ...in the form of a book, in the king's name, and witnessed by the leading personages of Church and State, including the queen, Ælftheryth, the king's grandmother, Eadgifu--the widow of Edward the Elder--Dunstan, Æthelwold, and Oswald. The Charter is preceded by a full-page miniature showing [King] Edgar between the Virgin Mary and St. Peter, offering the codex containing the Charter to Christ." (Backhouse, p. 47)

Detail of Virgin Mary

(Backhouse, pl. vi)

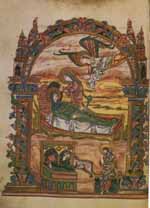

"A poem in gold at the beginning of the book states that it was written at the command of Æthewold, Bishop of Winchester, for his personal use, by one of his monks named Godeman...St. Æthewold was born at Winchester and as a young man was at the court of Æthelstan (reigned 924-39). ..In 963 Æthewold became Bishop of Winchester...He died in 984...The main contents of the benedictional...are special texts for use by a bishop when giving a solemn blessing at Mass, after the Lord's Prayer and before communion. This rite...was 'non-Roman'; it originated probably in Frankish lands...[but] was very popular during the Middle Ages." (Backhouse, p. 59)

Detail of St. Æthelwold

(Lasko, pl. 100)

"...the iconography of ivory carving [was close] to the manuscript illumination in monastic workshops. ..the figure style on the ivory is much closer to the Metz ivories...The stocky figures with thick, almost blanket-like draperies that bind them tightly like shrouds, and with heads that project their heavy jaws forwards are characteristic of the ivories, while the Benedictional's [see above] thin linear, sharply defined forms have more of the earlier, delicate Reimsian 'drawing' style in them...It has been argued that the relationship [to the Aethewold Benedictional] is not a direct one, but that it was probably a Metz manuscript...that probably came to England and was copied at Winchester" serving as a model for the later ivories. (Lasko, p. 71)

Detail of Mary

(Backhouse, pl. viii)

"It is uncertain whether the Robert [of the name] is the Archbishop of Rouen...from 990 to 1037, who was the brother of Emma of Normandy, queen successively of Æthelred and Cnut, or Robert of Jumièges...A very plausible patron for the manuscript is Æthegar, monk of Abingdon, the first abbot of Æthelwold's reformed New Minster, Bishop of Slesey 980, and Archbishop of Canterbury 988-90...[These benedictionals] contain the most important surviving painting in the Winchester style...with their strong, rich colouring and more statuesque figures they appear closer to the presumably Carolingian archetype." (Backhouse, p. 60)

Detail of supplicants

(Backhouse, pl. xi)

"This magnificent Gospels is set apart from other English manuscripts of the late tenth and early eleventh centuries by its distinctive palette...There are portraits of the four Evangelists, their symbols above them...Conspicuously absent are the flamboyant frames of acanthus typical of late tenth-century Winchester work and adapted at Canterbury in the early eleventh century." (Backhouse, p.68)

Detail of St. John

(Backhouse, pl. 44)

"Boethius was a Roman philosopher and statesman (c.480-c.524) . He became the friend and advisor of Theodoric, King of the Ostrogoths, but he eventually had Boethius executed on a charge of treason. While in prison beforehand Boethius wrote his celebrated De Consolatione Philosophiae, which tells how the soul attains through philosophy to knowledge of God. The work was extremely popular in the Middle Ages and was one of those translated into Old English by Alfred."

"At the beginning of his treatise Boethius sees in imagination 'a woman...having a grave countenance, glistening with clear eyes, and of a quicker sight than commonly Nature doth afford...' This is Philosophy...The zigzag hems of the drapery [are similar to those in] the Ramsey Psalter.

(Backhouse, pl. 46)

From "a copy of Prudentius's Psychomachia [1], written and illustrated in the late 10th century...The technique of the illustrations of all the Anglo-Saxon manuscripts of the Psychomachia [2] is outline drawing; they derive from a cycle of eighty-nine drawings which originated in the fifth century."

(Backhouse, p. 68)

Detail 1: "At the sight of Luxuia's chariot, glittering with gold and precious stones, men give up the fight.

Detail 2, Detail 3, Detail 4: "Men abandoning themselves to Luxoria."

(Oxford University Libraries)

'The Cædmon Manuscript": parts of Genesis, Exodus and Daniel in Old English verse, illustrated with Anglo-Saxon drawings, c. A.D. 1000.

Entire manuscript available at: Early Manuscripts at Oxford University, Bodleian Library, Junius MS. 11

(Ohlgren)

Vatican City, Biblioteca Apostilica, Vaticana MS Reg. lat. 12

Canterbury, Christ Church?; Bury St. Edmunds

Believed to have been created at the Canterbury scriptorium that produced the Harley MS.

(Ohlgren)

London, Bristish Library MS Cotton Cleopatra C. VIII, Canterbury, Christ Church

"The Psychomachia by Prudentius (Aurelius Prudentius Clemens, b. A.D. 348) was one of the most popular Latin poems of the early Middle Ages...[This manuscript] dates to the late tenth or early eleventh century...The poem recounts battles between seven pairs of virtues and vices, personified as warrior maidens."

Fides (Faith) and Veterum Cultura Deorum (Worship of Old Gods),

Pudicitia (Chastity) and Sodomita Libido (Lust of the Sodomite),

Patientia (Patience) and Ira (Anger),

Mens Humilis (Humility) and Superbia (Pride),

Sobrietas (Soberness) and Luxuria (Indulgence),

Operatio (Good Works) and Avaritia (Avarice),

Concordia (Concord) and Discordia (Discord).

f5: Abraham returns after freeing Lot. Lot's wife accompanies.

(Ohlgren)

London, Bristish Library MS Cotton Cleopatra C. VIII, Canterbury, Christ Church

(Ohlgren)

London, Bristish Library MS Cotton Cleopatra C. VIII, Canterbury, Christ Church

f11: Ira (Anger), holding a shield, strikes with a sword at Patentia, (in the next drawing Ira's sword breaks in pieces on Patentia's head!)

(Ohlgren)

London, Bristish Library MS Cotton Cleopatra C. VIII, Canterbury, Christ Church

f13: Patentia points towards Job and promises him peace

(Ohlgren)

London, Bristish Library MS Cotton Cleopatra C. VIII, Canterbury, Christ Church

f17: Humilitas, veiled, holds Superbia's severed head by the hair; Spes, veiled, standing onthe left, upbraids the dead Vice.

(Ohlgren)

London, Bristish Library MS Cotton Cleopatra C. VIII, Canterbury, Christ Church

f36: Sapientia

Oxford, Bodleian Library MS Junius 11, Canterbury, Christ Church?

"...contains four poems in Old English and a sequence of textual illustrations to Genesis."

"...Given the emphasis placed...on the rebellion of a prince against his king or lord, and the exile of a price with his royal retainers, it is plausible to speculate that these episodes...may refer to the tumultuous events leading up to the death of Aethelred and the elevation of Cnut to the throne in 1016."

Detail of top: Irad and his wife attended by a midwife.

Detail of center: Irad and his wife attended by a midwife.

Detail of bottom: Lamech with his wives Adah and Zillah.

Oxford, Bodleian Library MS Junius 11, Canterbury, Christ Church?

Detail of top: Jubal plays a lyre, Tubal-Cain is a blacksmith

Detail of center: Tubal-Cain, holding an axe, drives a plow.

Detail of bottom: Adam stands, Eve sits holding Seth

Oxford, Bodleian Library MS Junius 11, Canterbury, Christ Church?

Malaleel's death and burial. His son Jared holds the corpse while six males (his other sons) stand to the right. Three females (his daughters?) look on, two with faces veiled.)

(Harksen, pl. 6)

Detail of bronze portal of Hildesheim Cathedral.

(Lasko, pl. 203)

"...the sculptural reality of the carving is almost totally destroyed by the sharply incised network of surface drawing...there remain elements of the fluttery drapery so close to the Winchester style...the figures have the broad heads and jutting jaws [and] closely resemble the manuscript illumination dated to around 1100."

(Ohlgren)

London, British Library MS Harley 603, Canterbury, Christ Church

The psalmist is threatened by 4 persecutors.

"This profusely illustrated manuscript is the earliest of the three English copies of the Utrecht Psalter, which was made at the abbey of Hautvilles, near Rheims in the early ninth century."

f72 is drawn by Hand E: "who worked in the early years of the second quarter of the 11th century, did not follow the Utrecht Psalter as a model. Because two later artists revived the Utrecht iconography, it has been assumed that the manuscript was removed from Christ Church for a period of time...As a result, due to the absence of the model, artists E and F were forced to improvise." (cf. Judith E. Duffey who disagrees and asserts that the departure from the originals was deliberate and conscious.)

(Backhouse, pl. xiii)

"There are fifteen pages of decorated canon tables, miniatures of the four Evangelists, and decorative pages at the beginning of each gospel. Canon tables are tables devised by Eusebius of Caesara (c.260-c. 340), the biographer and ecclesiastical advisor of the Emperor Constantine the Great, to show the correspondences between the four gospel narratives. They are a standard inclusion in manuscripts of the gospels in the Middle Ages." (Backhouse, p. 68)

(Backhouse, pl. )

Begun in 10th century, left unfinished, illuminations added in the 11th century. "The manuscript has lost two evangelist miniatures. Those remaining show Matthew and Luke. The representation of Matthew is very closely related to that of him in the Lindesfarne Gospels. Especially to be noted is the appearance of a head from behind a curtain on the right, which possibly belongs to Christ in the role of inspirer of the gospel."

(Backhouse, pl. xiv)

"An inscription at the end of the book, probably by the donor himself, records that it was given to the Abbey of Jumièges when Bishop of London. Robert was a Norman by birth and a close friend of Edward the Confessor (King of England 1042-66). Be became Abbott of Jumièges in 1037, was Bishop of London 1044-51 and Archbishop of Canterbury 1051-2. He had to flee from England in 1052 and died later that year...The miniatures are extremely expressive, showing at once the Winchester school's expert draughtsmanship and its fondness for lavish colouring."

Detail of Mary and Attendant

(Backhouse, pl. 62)

Presentation of a gold cross to the New Minster by Cnut (reigned 1016-35) and his Queen, Ælfgifu (Emma of Normandy). "The Book of Life...of a church or monastery was meant as a draft entry for the eternal Book of Life of the Saved. The New Minster book states that it contains the names of the brethren and monks as also of the associates and benefactors, living and dead, of the Abbey. It was to be brought daily to the alter at one of the community's two solemn Masses by the subdeacon, who was then to read out some of the names in it." (Backhouse, p. 78)

Detail 1: Image of Mary

Detail 2: Image of King Cnut

Detail 3: Image of Ælfgifu (Emma of Normandy)

(Backhouse, pl. 60)

Early and mid-11th century. "These calendar scenes are the earliest surviving examples in English art of a cycle...of 'labours of the month' illustrations now known within the context of any medieval calendar, though certain features of their composition suggest that they may themselves have been based ultimately upon a late classical sequence."

(Coatsworth)

The ladies wear the wrap style head rail. The gentleman exhibits the classic wrinkled sleeves and shoulder-fastened cloak.

(Anglo-Saxon Index)

Queen Emma receives the Encomium Emmae from its author, while her sons Harthacnut and Edward look on.

(Backhouse, pl. 67)

"There is illumination of two dates in the manuscript. Original work [mid-11th cent.]includes drawings of the signs of the zodiac...and a full-page Crucifixion in tinted outline. This shows a very posed style of Anglo-Saxon drawing, in which pattern has taken the place of invention." >Backhouse, p. 83)

Detail of Mary

Detail of John

(Zarnecki, pl. 33)

"Anglo-Saxon manuscripts were sent to the continent as gifts, many to Normandy, some to Fleury and even further afield...Judith, countess of Flanders and wife of Tostig, Earl of Northumbria, gave two manuscripts...to the abbey of Weingarten." (Zarnecki, p. 199)

Detail of kneeling figure

(Zarnecki, pl. 219)

Though the Panel is part of a shrine in Spain, the work was probably done by a German artist, a number of which were in Spain at this time. The similarity to the Hildesheim doors (see "Eve Suckling Cain" above) is marked. (Zarnecki, p. 225)

"...from a small group [of carvings] that must be attributed to an English workshop probably active in the second half of the eleventh or early twelfth cent...the close fitting cap-like crown is one found more ofetn in the eleventh century than in the twelfth...In England such early naturalism can be found in the illumination of the Canterbury scriptorium...and in the Winchester style..." "It points to the period when craftsmen in North Western Europe were coming to terms with a new, more controlled, and fundamentally more stylised art."

(Lasko, p. 150)

This image shows a woman fleeing a house that has been set afire by William's troops upon landing in England.

(Zarnecki, pl. 227)

The "panel" drapery style "is a convention which appeared roughlyat the same time, about 100, in many centers in the west, its purpose being to give more volume to the human form by means of the garment which covers it...One of the earliest and most striking examples north of the Alps is found in the work of the Saxon goldsmith, Roger of Helmarshausen...Roger is thought to be identical with Theophilus, the aurhot of De diversis artibus, a monk who wished to remain anonymous and signed his work with that fictitious name. The celebrated treatise of about 100 gives instruction on the various techniques in painting, glasswork, and metalwork...Roger's style is similar in many ways to that of the Cluny manuscripts and the Berze wall paintings. He also articulates the human figure by a network of clinging folds of the "panel" type, but in his case it has a form that has been termed "nested V-folds..." (Zarnecki, p. 234)