from Lawrence Levine, Highbrow/Lowbrow

[p. 171]

THE CHILD BORN in 1900 would, then, be born into a new world which would not be a unity but a multiple." This terse comment, appearing only toward the end of Henry Adams's Education, was in fact a central thread that Adams embroidered throughout the third-person narrative of his life and times. "He had become an estray; a flotsam or jetsam of wreckage," Adams wrote of himself. "His world was dead. Not a Polish Jew fresh from Warsaw or Cracow . . . still reeking of the Ghetto, snarling a weird Yiddish to the officers of the customs‹but had a keener instinct, an intenser energy, and a freer hand than he‹American of Americans, with Heaven knew how many Puritans and Patriots behind him . . . he was no worse off than the Indians or the buffalo who had been ejected from their heritage by his own people." Shortly before Adams had his autobiography privately printed and circulated among a small group of friends in ~907, the period's other famous Henry‹Henry James‹visited his native land after almost a quarter of a century of self-exile. Like Adams, James was seeking to recover "some echo of the dreams of youth, the titles of tales, the communities of friendship, the sympathies and patiences . . ." Like Adams, he was to find "among the ruins" of his country, not the "New England homogeneous" he remembered, not the unity he sought, but rather "multiplication, multiplication of everything . . . multiplication with a vengeance.''1

For James, as for Adams, the word "multiple" came to symbolize the new world. For James, as for Adams, the immigrant was a convenient and tangible sign of a transition that left him with "a horrible, hateful sense of personal antiquity," with a numbing sense of being an alien in his own land. He visited Ellis Island and came away like a person "who has had an apparition, seen a ghost in his supposedly safe old house." He toured New

[p. 172]

York's Lower East Side and felt "the 'ethnic' apparition again sit like a skeleton at the feast. It was fairly as if I could see the spectre grin." He rode on the electric cars and gazed upon "a row of faces, up and down, testifying, without exception, to alienism unmistakable, alienism undisguised and unashamed," which made him "gasp with the sense of isolation." He walked the streets and found that "face after face, unmistakably, was 'low'‹particularly in the men." Even in Boston, where he stood on Beacon Hill one late winter Sunday afternoon, close to the State House and the statues, observing the strolling crowds of workers "of the simpler sort" dressed in their Sunday best, he discovered that "no sound of English, in a single instance, escaped their lips; the greater number spoke a rude form of Italian, the others some outland dialect unknown to me . . . No note of any shade of American speech struck my ear, . . . the people before me were gross aliens to a man, and they were in serene and triumphant possession." The general movement, he lamented "was away‹away always and everywhere, from the old presumptions and conceivabilities."2

It was not only the immigrants, their numbers and manners, that filled James with "the dreadful chill of change," but the general tone and tenor of his native land, where "the will to grow was everyw` here written large, and to grow at no matter what or whose expense." He was shocked by the "vision of waste" that left row-s of houses "marked for removal, for extinction, in their prime There was no better symbol of the "profane overhauling" that had left America a "hustling, bustling desert" than the "insolent skyscrapers, those "vast money-making" structures, those "impudently new . . . payers of dividends," those "monsters of the mere market," which now overwhelmed such aesthetically and spiritually satisfying landmarks as New York's Trinity Church or Castle Garden, from whose stage the young Henry James had heard the young soprano Adelina Patti "warbling like a tiny thrush even in the nest." Today this "ancient rotunda" was "shabby, shrunken, barely discernible." Worse still, Boston's Athenaeum, "this honored haunt of all the most civilized‹library, gallery, temple of culture," was now "put completely out of countenance by the mere masses of brute ugliness . . . above the comparatively small refined facade . . . It was heart-breaking." It

[p. 173]

was not merely tradition that was in danger but taste itself. James complained that "the huge democratic broom" had swept away the old and ushered in an age of "the new, the simple, the cheap, the common, the commercial, the immediate, and, all too often, the ugly." Everywhere in this "vast crude democracy of trade" James was assaulted by the "overwhelming preponderance" of the businessman. In this "heaped industrial battle-field" James was "haunted" by a "sense of dispossession." Constantly he was forced to tighten his "aesthetic waistband," to protect himself against "the consummate monotonous commonness, . . . in which relief, detachment, dignity, meaning, perished utterly and lost all rights."3 . . .

[p. 176]

. . . In an industrializing, urbanizing nation absorbing millions of immigrants from alien cultures and experiencing an almost incomprehensible degree of structural change and spatial mobility, with anonymous institutions becoming ever larger and more central and \with populations shifting from the countryside and small town to the city, from city to city, and from one urban neighborhood to another, the sense of anarchic change, of looming chaos, of fragmentation, which seemed to imperil the very basis of the traditional order, was not confined to a handful of aristocrats. Indeed, the elites had more allies than they were ever comfortable with, for to many of the new industrialists as well as many members of the new middle classes, following the lead of the arbiters of culture promised both relief from impending disorder and an avenue to cultural legitimacy.

As he surveyed the changes in his country in the early years of this century, Henry James lamented that there was no escape "into the future, or even into the present; there was an escape

[p. 177]

but into the past." James was not quite accurate. For him and for many others there was also an escape into Culture, which became one of the mechanisms that made it possible to identify, distinguish, and order this new universe of strangers. As long as these strangers had stayed within their own precincts and retained their own peculiar ways, they remained containable and could be dealt with: Afro-Americans dancing their strange ritual dances to exotic rhythms within their own churches; Irish women "keening" [wailing] weird melodies over their dead at their own wakes; Germans entertaining family and friends in their own beer gardens. But these worlds of strangers did not remain contained; they spilled over into the public spaces that characterized nineteenth-century America and that included theaters, music halls, opera houses, museums, parks, fairs, and the rich public cultural life that took place daily on the streets of American cities. This is precisely where the threat lay and the response of the elites was a tripartite one: to retreat into their own private spaces whenever possible; to transform public spaces by rules, systems of taste, and canons of behavior of their own choosing; and, finally, to convert the strangers so that their modes of behavior and cultural predilections emulated those of the elites‹an urge that I will try to show always remained shrouded in ambivalence. Martin Green has said of Charles Eliot Norton that "he and his colleagues brushed back an ocean in which they fully expected to drown." Norton himself, governed by his characteristic pessimism about the future, probably would not have agreed, but in retrospect it is fair to say that he and his peers were more successful than they could have expected. They left behind them‹firmly planted on high ground‹enclaves of culture that functioned as alternatives to the disorderly outside world and represented the standards, if not the total way of life, they believed in.7

ONE OF THE SEVERAL factors underlying John Philip Sousa's importance as a cultural figure at the turn of the century was his image as an apostle of order in an unstable universe. The Worcester Telegram described how Sousa got what he wanted from his

[p. 178]

men with the "simple lash of his eye, the motion of his little finger." In ~892 a newspaper in Rockford, Illinois, commented that Sousa "woos the harmony out of the men with the air of a master." Sousa was hailed as a leader and commonly compared to a general, a figure he certainly resembled in his smart military uniform. "Not the least enjoyable thing about a Sousa band concert," the Detroit Tribune observed in I899, "is the masterly control of the leader over the human instrumentality before him." Sousa himself encouraged these views. "I have to work so that I feel every one of my fifty-eight musicians is linked up with me by a cable of magnetism," he told a reporter. "I know precisely what every one of my musicians is doing every second or fraction of a second that I am conducting. I know this because every single member of my band is doing exactly what I make him do.18

In depicting himself as a force for disciplined order, Sousa touched a chord that ran deep at the turn of the century. "America! America!" school children were taught to sing in the 1890s,

God mend thine ev'ry flaw,

Confirm thy soul in self-control

Thy liberty in law.

In 1914, shortly after the outbreak of war in Europe, Henry Lee Higginson, now almost eighty years old, stood before his orchestra and pleaded with his musicians for order

We meet again under difficult circumstances; we are of many nationalities . . . and we are all on American soil, which is neutral. Therefore, we must use every effort to avoid all unpleasant words or looks, for our task is to make harmony above all things‹ harmony even in the most modern music. I expect only harmony.

If Higginson was particularly insistent that his musicians treat one another harmoniously it was because he had long understood that before culture could spread order and harmony throughout the land it had to clean its own house, discipline its audiences and performers, and stand as an exemplar for the nation.9

"Harmony" and "order" are hardly the words one would choose to describe American audiences from the eighteenth to the late nineteenth centuries. In 1766 Edward Bardin announced a series of outdoor concerts in New York City and felt it necessary

[p. 179]

to declare that "every possible precaution will be used to prevent disorder and irregularity." The playbill advertising a Baltimore concert in the late summer of I796 featuring the music of Haydn, Playel, and Bach, concluded by noting, "A number of constables will attend to preserve order." That such precautions were needed is attested to by an indignant letter in the New York Post Boy in the waning days of I764 from "a dear lover of music" who complained that "instead of a modest and becoming silence nothing is heard during the whole performance, but laughing and talking very loud, squalling, overturning the benches, etc. - behaviour more suited to a {?imbroglio than a musical entertainment." Such scenes were evidently common enough that newspapers often reviewed the audience as well as the performers. In I786 the Pennsylvania Packet concluded a review of Handel's Messiah by noting, with what seemed relief, "No interruption from within, no disturbance from without, prevented the full enjoyment of this Grand Concert." 10

The tendency for undisciplined audiences to treat theaters, concert halls, opera houses, even lecture halls, not as sacred precincts but as places of entertainment where they could act naturally, continued well into the nineteenth century as we have seen in the last two chapters. The very ethos of the times encouraged active audience participation. "It is the American people who support the theatre," the Boston Weekly Magazine asserted in 18z4, "and this being the case, the people have an undoubted right to see and applaud who they please, and we trust this right will never be relinquished. No, never!" The New York Mirror urged its readers in I836 to make themselves heard: "Applaud whenever there is the least thing meriting admiration. It sustains, cheers and inspires the actor, warms him into full exertion, and often, in laborious scenes, affords him a moment of sweet and necessary repose. It also cheers the audience themselves, breaks the monotony of a continued and perhaps crowded confinement in one position, and renders them as much more able to appreciate excellence as it does the performer to exhibit it . . . Applaud the performers!!" Ticket holders, a New Orleans judge ruled in I853, had the legal right to hiss and stamp in the theater. Audiences of the period seemed fully prepared to heed this advice and exercise their rights.l1

The gap between the stage and the pit or orchestra, which we

[p. 180]

have learned to treat as a boundary separating two worlds, was perceived by audiences for much of the nineteenth century as an archway inviting participation. In his memoirs, Max Maretzek described a complicated feud that Edward P. Fry, the manager of the Astor Place Opera House, had with three of his singers and their ally, the publisher James Gordon Bennett of the New York Herald. As with the Forrest-Macready feud, it did not take long for the audience to get into the fray. During a performance of Norma in December I848, the tenor Sesto Benedetti walked onto the stage and according to Maretzek, "He was immediately greeted by a storm of hisses, which were as quickly broken in upon by thunderous acclamation. This at length stilled and he began to sing." His singing was accompanied by "screams, whistles, clapping of hands, hisses, trampling of feet, roaring, menacing outcries and gesticulations of every kind." Maretzek imagined that "the inmates of some half a hundred mad-houses had broken loose." After numerous attempts, Fry was able to address the audience and convince it to allow the opera to continue, but the audience remained rambunctious and difficult, laughing hilariously even at lines in Italian they could not have known the meaning of. Some yelled for Benedetti to sing "Yankee Doodle," others shouted "We don't want 'Yankee Doodle' 'Carry him back to Old Virginey.'l2

Audiences remained proudly independent and insisted upon receiving what they had been promised and judging openly what they received. When he was touring the United States, the British actor Henry Irving was told of a city in Colorado where the manager of a traveling company, in order to catch a train taking his troupe to their next engagement, condensed the performance of his play into an hour and a half. The next time the company visited that city "they were met en route, some fifty miles out, by the sheriff, who warned them to pass on by some other way, as their coming was awaited by a large section of the able-bodied male population armed with shot guns." As late as I907, the audience at a performance of The Barber of Seville in El Paso, Texas, erupted into riotous behavior when the advertised tenor, Leandro Campanari, failed to appear and a scene in Act I, and several scenes in Act II were omitted. In spite of the insistence of the company's manager, Henry Russell, that the performance

[p. 181]

was precisely the one given in every other city and the efforts of the soprano Alice Nielsen to appease the crowd by singing "Swanee River," "Coming through the Rye," and "Annie Laurie," for which effort she was roundly hissed, the knowledgeable audience demanded a complete rendition of the opera they had paid to hear. Even the arrival of police failed to quell the audience, which stormed the box office in an ultimately successful effort to have their money refunded.l3

Although audiences did not generally express themselves quite so dramatically, their independence was commonly manifest. After a concert in Stamford, Connecticut, in I863, Louis Moreau Gottschalk noted in his journal, "The concert was deplorable this evening. Complete silence. I correct myself. Silence when I entered and when I went out, but animated conversation all the time I was playing." So unruly were his audiences that when a young man tiptoed quietly and unobtrusively across the hall during his concert in Williamsport, Pennsylvania, Gottschalk wrote, "Incomparable young man! How I regret not being able to inscribe thy name on my tablets or have it engraved in letters of gold, in order that it may be handed down to the admiration of posterity!" The young Henry Finck complained of the lack of musical culture and manners in the Oregon town where he grew up. On one occasion a "young rowdy began, while we played, to whistle a comic song‹yes, while we played!" He wrote bitterly of those who "when you play a sonata of Beethoven or an overture by Mozart for them . . . listen a few moments then start up from their chairs, whistle 'Marching Through Georgia' and show their ill breeding in all other possible ways." Though he lived far from Oregon, George Templeton Strong often felt as if he too was a denizen of the frontier. After attending a New York Philharmonic concert in I858 he commented in his diary, "crowded and garrulous, like a square mile of tropical forest with its flocks of squalling paroquets and troops of chattering monkeys." There were exceptions to this disorder, of course, and Strong wrote happily of the "great, silent, appreciative crowd of Teutons" among whom he sat at an I859 concert commemorating the centennial of Schiller's birth, but such homogeneity of people and purpose was hard to come by.l4

That Strong's complaints were not the product of a crotchety

[p. 182]

imagination is made clear by the actions of the Philharmonic's board. In their thirteenth annual report (I855), the directors complained of "the disgraceful habit of talking aloud at the rehearsals while the performance is going on," and rebuked those who "would seem to be more attracted and charmed by the sounds of their own voices, than by the inspiring, solemn, majestic tones of BEETHOVEN or MENDELSOHN. In I875 John Sullivan Dwight wrote of "those illbred and ignorant people" at Theodore Thomas's New York concerts "who keep up a continued buzzing during the performance of the music to the annoyance of all decent folk." At the American premiere of Lohengrin in 1871 at the Stadt Theatre in New York City, a reviewer was shocked by those in the audience who waited for the program to begin by chewing on oranges and spitting out the rinds. Others were no less surprised at the decision of the society leader Mrs. W. Bayard Cutting to break the monotony of a lengthy program at the Metropolitan Opera by having the contents of a sandwich hamper distributed among her guests, who nibbled bonbons and other delicacies during the singing. In 1891 the Board of Directors of the Metropolitan Opera House felt compelled to post the following notice in every box:

Many complaints having been made to the directors of the Opera House of the annoyance produced by the talking in the boxes during the performance, the Board requests that it be discontinued.

Whispering, talking, laughing, coughing, shouting, shuffling, arriving late, leaving early, prematurely donning outer garments during the final number, noisily turning the pages of programs, stamping of the feet, applauding promiscuously, insistently demanding encores, sneaking snacks, spitting tobacco‹the list of audience sins was long and troublesome.

Some of these sins were manifest in the nation's art museums as well. When in 1891 New York's Metropolitan Museum of Art, after prolonged prodding by political leaders, decided to open its doors to the public on Sunday afternoons, the staff braced itself to greet a crowd of twelve thousand that was younger, more working class in its composition, and less used to the decorum of art museums than the Metropolitan's usual

[p. 183]

run of visitors. The New York Times announced that "Kodak camera fiends" would be barred and that visitors would have to check canes and umbrellas at the door "so that no chance should be given for anyone to prod a hole through a valuable painting, or to knock off any portion of a cast." A Boston Herald reporter testified that many came armed with large baskets of lunch and restless babies. Some, according to Louis P. di Cesnola, the Metropolitan's director, "brought with them peculiar habits which were repulsive and unclean." Cesnola noted that the visitors were accustomed to the Dime Museums on the Bowery "and had come here fully expecting to see freaks and monstrosities similar to those found there. Many visitors took the liberty of handling every object within reach; some went to the length of marring, scratching, and breaking articles unprotected by glass; a few proved to be pick-pockets." The New York Times, which had been a strong advocate of Sunday opening, had a more benign view of the results than Cesnola, though even its account transmits a sense of the disorder that so troubled the Metropolitan's patrons: "Not an arrest was made and not a person was violently ejected," it reported. "Gleeful voices were heard through the corridors . . . Boys tagged at their mothers' heels and laughed at the queer-shaped pottery of the Egyptians. But they did no harm. A few could not help putting a hand on the piece of statuary now and then, but this is done just as much on a week day, and cannot be spoken of as an evil exclusively attending Sunday opening.''l6

Almost as soon as he became superintendent of New York's Central Park in I857, Frederick Law Olmsted complained of a "certain class" of visitors which believed "that all trees, shrubs, fruit and flowers are common property," and would not hesitate to graze their animals and gather firewood and any available flowers and fruits. "A large part of the people of New York," he observed, "are ignorant of a park . . . They will need to be trained to the proper use of it, to be restrained in the abuse of it." Three years later he complained to the park's Board of Commissioners that inadequate policing had led to robbery, "wanton defacement" of park property, tobacco spitting, garbage dumping, "and other filthy practices." The problem of unruly audiences invaded even the staid precincts of the Smithsonian Institution. In his

[p. 184]

report of I859, Joseph Henry commented that while many of those attending the institution's lecture series did so "for the sake of the advantage to be derived from them," many others "attend as a mere pastime, or assemble in the lecture room as a convenient place of resort, and by their whispering annoy those who sit near them." Since Henry was never convinced that such public lectures ought to be part of the Smithsonian's mission, he simply took advantage of the fire of I865 and had his building reconstructed without a lecture hall.17

Other cultural leaders lacked this easy resolution and were compelled to confront the disorder directly. Even as they were successfully establishing canons that identified the legitimate forms of drama, music, and art and the valid modes of performing and displaying them, the arbiters of culture turned their attention to establishing appropriate means of receiving culture. The authority that they first established over theaters, actors, orchestras, musicians, and art museums, they now extended to the audience. Their general success in disciplining and training audiences constitutes one of those cultural transformations that J have been almost totally ignored by historians. . . .

[p. 198]

The relative taming of the audience at the turn of the century was part of a larger development that witnessed a growing bifurcation between the private and the public spheres of life. Through the cult of etiquette, which was so popular in this period, individuals were taught to keep all private matters strictly to themselves and to remain publicly as inconspicuous as possible. Norbert Elias has shown that with the new societal corm plexities and differentiation of social functions, an entire range

[p. 199]

of intimate activities‹eating, coughing, spitting, nose blowing, scratching, farting, urinating‹were firmly removed from the public sphere to that of the private. Such activities were now restricted to special "temporal and spatial enclaves." People were similarly taught to remove from the public to the private universe an entire range of personal reactions. "A lady or gentleman should conduct herself or himself on the street so as to escape all observation," an etiquette book advised in I892. "A shrill voice, a loud laugh, . . . occupying the center of the sidewalk are all very bad form." Or as another guide put it, "Never look behind you in the street, or behave in any way so as to attract attention. Do not talk or laugh loudly out of doors, or swinging your arms as you walk. If you should happen to meet some one you know, take care not to utter their names loudly." As John Kasson has recently put it, the individual mirrored the increasing segmentation of society in a segmentation of self. Reactions and emotions had to be carefully governed. In the sense that theaters, opera houses, symphony halls, and art galleries, as well as the larger movie theaters and vaudeville houses, reflected this process they were mirrors of society. But they were more than that; they were active agents in teaching their audiences to adjust to the new social imperatives, in urging them to separate public behavior from private feelings, in training them to keep a strict reign over their emotional and physical processes.35

Just a week before Christmas 1914, Boston concertgoers were introduced to Schoenberg's Five Pieces for Orchestra, whose concepts of harmony and melody were largely foreign to them. The critic Olin Downes, who characterized the music as "not only intricate in its rhythms and in its polyphony, but also, for the most part, very ugly," felt that Karl Muck conducted it out of a sense not of admiration but of duty, and at its close "marched off the stage, apparently in an unamiable frame of mind." Yet the audience accepted it all without a murmur. "Nothing was thrown at Dr. Muck and the orchestra," the critic Philip Hale reported. "There was no perturbation of Nature to show that Schonberg's pieces were playing; the sun did not hasten its descent; there was no earthquake shock. It was as it should have been in Boston."36 He might have added that this was the way it was rapidly becoming in the United States as a whole: . . .

[p. 221]

. . . The crusade for culture in America, then, was to a significant extent a struggle to bring into fruition on a new continent what the crusaders considered the traditional civilization from ~-which the earliest Americans sprang and to which all Americans were heir. The primary obstacle to the emergence of a worthy American music, Frederick Nast asserted in 1881, "lies in the diverse character of our population . . . American music can not be expected until the present discordant elements are merged into a homogeneous people." It was obvious under whose auspices the "merger" was to take place. In I898 Sidney Lanier argued that it was time for Americans to move back "into the presence of the Fathers" by adding the study of Old English to that of Greek and Latin, and by reading not just The odyssey but Beowulf "Our literature needs Anglo-Saxon iron; there is no ruddiness m its cheeks, and everywhere a clear lack of the red 0~~ American society, Henry Adams observed in his autobiography<~. "offered the profile of a long, straggling caravan s~ loosely towards the prairies, its few score of leaders far in - advance and its millions of immigrants, negroes, and Indians far in the rear, somewhere in archaic time."59

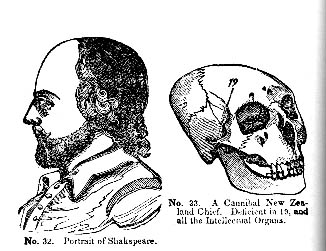

It should hardly surprise us that such attitudes informed the adjectival categories created in the late nineteenth century- to define types of culture. "Highbrow," first used in the ~8&>s to describe intellectual or aesthetic superiority!. and "lowbrow," first used shortly after I900 to mean someone or something neither

[p. 222]

"highly intellectual" or "aesthetically refined," were derived from the phrenological terms "highbrowed" and "lowbrowed," which were prominently featured in the nineteenth-century practice of determining racial types and intelligence by measuring cranial shapes and capacities. A familiar illustration of the period depicted the distinctions between the lowbrowed ape and the increasingly higher brows of the "Human Idiot," the "Bushman," the "Uncultivated," the "Improved," the "Civilized," the "Enlightened," and, finally, the "Caucasian," with the highest brow of all. The categorization did not end this broadly, of course, for within the Caucasian circle there were distinctions to be made: the closer to western and northern Europe a people came, the higher their brows extended. From the time of their formulation, such cultural categories as highbrow and lowbrow were hardly meant to be neutral descriptive terms; they were openly associ

[p. 223]

ated with and designed to preserve, nurture, and extend the cultural history and values of a particular group of peoples in a specific historical context.60

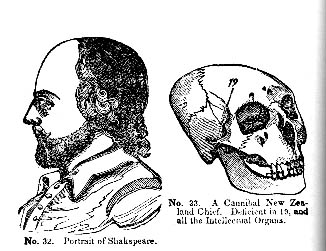

No. 32. Portrait of Shakespeare.

This typical illustration from Coomb's Popular Phrenology, 1865, demonstrates the widespread interest in the shape and measurement of brows. The high brows of such figures as Shakespeare, Milton, and Dickens, especially when contrasted with the pitifully low brows of alien races, became emblematic of culture and intelligence.

Increasingly, in the closing decades of the nineteenth century, as public life became everywhere more fragmented, the concept of culture took on hierarchical connotations along the lines of Matthew Arnold's definition of culture‹"the best that has been thought and known in the world . . . the study- and pursuit of perfection." The Englishman Arnold, whose critical reception preceded his trips to America in I883 and I886, did not discover a tabula rasa in America; he found many eager constituents here from the very beginning. Two years before Arnold's Culture o~ Anarchy was published, Harper's maintained that certain a~ were "not only tests of taste but even of character." If a man gave himself to Shakespeare or Chaucer, "we have a clew to the man."

The man who among all Operas prefers Don Giovanni or Fidelio or the Barber of Seville, or Robert le Diable, involuntary- unveils himself as he makes his preference known. He rises or falls near or far in our regard just as he instinctively likes or rejects what you feel to be best.

Nevertheless, Arnold was perhaps the single most significant disseminator of such attitudes and had an enormous influence in the United States.* The Arnold important to America ~s not Arnold the critic, Arnold the poet, Arnold the religious thinkr. but Arnold the Apostle of Culture. "I shall not go so far as ~ say of Mr. Arnold that he invented" the concept of culture Henry James commented in 1884, "but he made it more definite than it had been befor-e‹he vivified and lighted it up." Arnold had his detractors. Walt Whitman dismissed him as "one of the dudes of literature," and complained to Horace Traubel that Arnold

*In his scholarly assessment of Arnold's influence in the ~ United 8u~ States Henry Raleigh concluded that "Arnold's success in America" ~ as immediate far reaching, and lasting. In the academic world in particular Ix has become a fixed star. It would not be an overstatement to say. as se`-everal nineteenth century admirers of Arnold did say, that he had perhaps more readers in America than he had in England itself."

[p. 224]

brought to the world what the world already had a surfeit of‹ "delicacy, refinement, elegance, prettiness, propriety, criticism, analysis: all of them things which threaten to overwhelm us." Whitman was in the minority. More typical was William H. Dawson, who proclaimed in ~904, sixteen years after Arnold's death, "There is today a cult of Matthew Arnold; it is growing; it must grow. It will grow." "Why does nobody any more mention Arnold's name? " Ludwig Lewisohn asked in I927 and replied that it was because Arnold's views had become completely absorbed in the mainstream of American thought.6'

The ubiquitous discussion of the meaning and nature of culture, informed by Arnold's views, was one in which adjectives were used liberally. "High," "low," "rude," "lesser," "higher," "lower," "beautiful," "modern," "legitimate," "vulgar," "popular," "true," "pure," "highbrow," "lowbrow" were applied to such nouns as "arts" or "culture" almost ad infinitum. Though plentiful, the adjectives were not random. They clustered around a congeries of values, a set of categories that defined and distinguished culture vertically, that created hierarchies which were to remain meaningful for much of this century. That they are categories which to this day we have difficulty defining with any precision does not negate their influence. Central terms like "culture" changed their meaning, or at least their emphasis, in the second half of the nineteenth century. In early nineteenth century editions of Webster's dictionary the primary definition of culture was agricultural: "The act of tilling and preparing the earth for crops; cultivation; . . . The application of labor or other means in producing; as the culture of corn, or grass." By the second half of the nineteenth century, while the agricultural definitions held, culture was defined as "the state of being cultivated . . . refinement of mind or manners." Words like "enlightenment," "discipline," "mental and moral training," and "civilization," cropped up freely in the definitions. The word cultivate, in addition to its agricultural meaning, was defined as "to civilize; as to cultivate the untamed savage." In I898 The People's Webster Pronouncing Dictionary and Spellin,g Guide, a pocket dictionary of 23,000 words with single-word definitions, defined "culture" simply as "refinement." By 1919 Webster's Army and Navy Dictionary and an elementary school edition of Webster's New Stan

[p. 225]

dard Dictionary armed American servicemen and school children with precisely the same succinct definition.62

It was this concept of culture that Henry James had in mind when, some thirty years after the Astor Place Riot, he pronounced it a manifestation of the "instinctive hostility of barbarism to culture." The new meanings that became attached to such words as "art," "aesthetics," and "culture in the second half of the nineteenth century symbolized the consciousness that conceived of the fine, the worthy, and the beautiful as existing apart from ordinary society. In ~894 Hiram SL Stanley- defined the "masses" as those whose sole delight rested in -e~ drinking, smoking, society of the other sex, with dancing music of a noisy and lively character, spectacular shows, and athletic exhibitions." Anyone demonstrating "a permanent taste for higher pleasures," Stanley argued, "ceases, ipso facto, to belong to the 'masses."' This practice of distinguishing "culture-" from lesser forms of expression became so common that b~ 1915 Van W~ Brooks concluded that between the highbrow and the lowbrow there is no community, no genial middle ground." - ~ What side of American life is not touched by this antithesis?" Brooks "asked "What explanation of American life is more central or more illuminating?" The process that had seen the noun "class" take on a series of hierarchical adjectives‹"lower," "middle ~.~ "working"‹in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries was operative for the noun "culture" a hundred years 1~ Just as the former development mirrored the economic changes brought about by the Industrial Revolution in England so ~e latter reflected the cultural consequences of modernization. . .

[p. 235]

In the late nineteenth century, and well into the twentieth, culture became an icon as never before. Even while anthropology was redefining the concept of culture intellectually, aesthetically it proved remarkably impervious to change; it remained a symbol of all that was fine and pure and worth. Whatever Franz Boas and Ruth Benedict might have meant by culture and how-ever influential their meaning ultimately was, Charl;ie Chaplin knew what the society meant by Culture and he and the Ma" Brothers and a legion of other popular comedians built parodies of that meaning into the very heart of their humor: they, c'~ a rapport with their audiences that generated a sense of complicity - -in their common stand against the pretensions of thc p - ~s of high culture. Thus when Chaplin, clad in his rags and twirling a cane, mocked cultured gentility as he selected, with meticulous nr~ deliberation, a butt from his sardine-tin cigarette ~r and ht lit it while strictly observing all the proper forms, he was speaking for his audience as well as himself. So too were the Mars Brothers when they created havoc in the opera house‹which ironically}v had become the very citadel of high culture in the popular imagination‹by tricking the orchestra into playing '`Take Me oat to the Ball Game" in the middle of the overture to n Il Trovatore. giving Groucho the opportunity to ply the aisles dispensing the snacks of common folk to the cry of "Peanuts! Peanuts!"

Although the stated intention of the arbiters of culture was to proselytize and convert, to lift the masses up to their level in fact their attitudes often had the opposite effect. The negative stereotypes of terms like "culture" and "cultivated" took hold early; the term "highbrow" was still young when it became a term of popular derision. When Harvard President Charles U:. Eliot spoke to the National Educational Association on the definition of the "Cultivated Man," in 1903, he was quick to point out, "I propose to use the term cultivated man in only its good sense‹in Emerson's sense. In this paper he is not to be a weak critical, fastidious creature, vain of a little exclusive information or of an uncommon knack in Latin verse or mathematical logic." True culture, Eliot assured his listeners, "is not exclusive, sectarian or partisan, but the very opposite." Such assurances did not seem to penetrate very deeply into the society. For much of this century significant segments of the American population remained at best ambivalent about and often hostile toward the

[p. 236]

"high" cultural categories and definitions that were established at the turn of the century. It is common to attribute this to some deeply rooted anti-intellectualism, and certainly there is more than a little validity in the notion, but as Martin Green has observed it is frequently "not so much intellectualism as intellectual authority which is resisted and resented."74