The Matrix of Modernity: Industrialization and Everyday Life

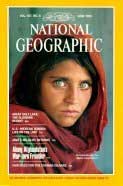

In

1985, National Geographic featured this striking photo of an

Afghan teenaged girl, a war refugee, on its cover. The picture

became immediately famous, and over the next two decades was

frequently used by National Geographic in its promotional

materials. It became part of National Geographic's brand

identity. By the late 1990s, it is likely that many Americans,

perhaps most of us, had seen the picture in one form or another at

various times.

In

1985, National Geographic featured this striking photo of an

Afghan teenaged girl, a war refugee, on its cover. The picture

became immediately famous, and over the next two decades was

frequently used by National Geographic in its promotional

materials. It became part of National Geographic's brand

identity. By the late 1990s, it is likely that many Americans,

perhaps most of us, had seen the picture in one form or another at

various times.

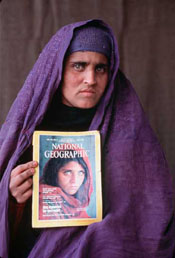

In January of 2002, the man who had taken the original photograph, Steve McCurry, returned to Afghanistan to try to find the woman who we had all seen so many times. After much effort, he found a woman, Sharbat Gula, who was probably the person in the original photograph. In the intervening years, she had continued to live a difficult, war-torn, and poverty-stricken life. (For more details, see http://magma.nationalgeographic.com/ngm/afghangirl/.)

For our purposes, one of the most stunning facts of this

heartbreaking story is that before this, Sharbat Gula had never

seen the original picture. Living a harsh life in refugee camps

and remote rural parts of Afghanistan, she had come into very

little contact with Western media of any sort, much less slick

magazines or advertising inserts. So millions upon millions of

Americans and others worldwide had viewed this picture, but the

person in the picture itself had not.

How could this happen? It is not about simple distance, that she lives far away from the U.S. People who live even farther away, in places like Australia or Japan, also frequently saw this picture. The reason is that Sharbat Gula lives off the grid of the modern media system, outside the matrix of modern systems of communication.

This course is, in a sense, about what it means to live within the grid of the modern world with its modern systems of communication -- about what it means to live "inside the matrix."

And to understand the significance of something that is so ordinary to us, it helps to think about life off the grid. About half of the population of the world has never made a phone call. Most of the people in the world do not have indoor plumbing. Only a small fraction of the world population owns a car. Fact is, the world that you, an American college student, live in is radically different from the world most people on the planet live in. The difference between the world that most people live in and the world that you and I live in, the difference between a world rooted to the land and a world afloat in a sea of elaborate technologies, has prompted a great deal of wonder and reflection over the years. The broadest term for the shift from agricultural life to industrialized life is "modernization." Understanding modernization is one of the core problems of the field of sociology.

Modern life is characterized on the one hand by the rise of heavy industry, the use of modern technological production methods (i.e., ways of making stuff), things like factories, railroads, and stock exchanges. But it is also characterized by dramatic changes in the ways people lead their everyday lives -- changes in how we talk to each other, raise our children, go through our day, and so forth. Modern media both are a product of modernization -- everything from newspapers to TVs come from factories -- and are themselves one of the key features of modernized life. Media play a key role in making modernity what it is.

Stage theories of social development

But what, exactly, is modernity? There are quite a few theories that try to explain modernization. Many of these are "stage theories of social development," that is, theories that suggest that human societies work their way gradually through several "stages" of development. Karl Marx, for example, thought that the first stage was hunter-gathering societies, which then evolved into agricultural societies (of various sorts), and then became feudal societies. As he was writing his books in the 1800s, he observed what he thought was the next stage of development, capitalism, breaking out all around him. The author of Future Shock, Alvin Toffler, had political views pretty much the exact opposite of Marx's (Toffler is an associate of Newt Gingrich, a conservative Republican former member of the US Congress), but also believes in a stage theory of development. The difference between Marx and Toffler is what they think should happen next: Marx thought the next stage after capitalism would (or at least should) be socialism, whereas Toffler thinks the next stage is an "information society."

Problems with Stage theories

Stage theories of social development can seem pretty compelling, even obvious, but the difference between Marx and Toffler points to the fact that "stages" of development are less obvious than you may think. Not long after Marx died, for example, the world's first major socialist revolution took place in Russia, a country that was still largely feudal; it hadn't gone through capitalism yet. (Lenin, the leader of the Soviet revolution in Russia, had to spend a lot of intellectual energy trying to explain how Marx could still be right given that fact.) People like Toffler who believe we are moving into an information society have a hard time explaining why traditional industrial capitalism still seems so powerful; many people have computers and use the internet, but we still drive to work in offices and factories and are heavily dependent on things like gasoline. (This is particularly an issue for people who believed Toffler's theory about the information society and invested heavily in internet stocks in the late 1990s, and subsequently lost their money in the internet stock collapse of 2000-2001.)

The moral of the story is this: modernization is certainly an important phenomenon in human life, but it is tricky to categorize and make sense of. Modernization is happening all over the globe as you read this, but predicting or generalizing about how it happens is a risky, uncertain business.

The Case of Oral Culture and the Print Revolution

One way to think carefully about the role of media in modernization is to look at past socio-cultural changes related to communication, such as the shift from an "oral culture" to a "print culture," from a world where most communication is almost entirely verbal to one where much of the most crucial forms of communication occur in writing and print. We live in a print culture: we think of illiteracy as a social problem. But it was not always so. Charlemagne, Socrates, and Alexander the Great, three of the great figures of history, were both illiterate and no one thought of it as a problem at the time. They lived in oral cultures, in societies where most of life took place through spoken language.

Oral culture

Today, it is very hard to imagine for us what it was like in an oral culture. "A man's word is his bond" is a saying left over from oral culture. But could you imagine buying, say, a load of groceries on a promise and a handshake? No. Today, instead, our version of a promise and a handshake is a printed document with a written signature on it -- a check. A check is not money, it's just a promise, but as print culture people, we demand it in writing. In oral cultures, it's the reverse; people trust the spoken word, not scribbles on paper.

In oral cultures, all interaction is interpersonal. There's little or no division between impersonal-official communication and the interpersonal. The speaker always has contact with their audience; even for the King, communication was always interactive, (and not one way, like print).

Today, one of the closest things we have to oral culture is evident in the "Call and Response" tradition, where someone in front of a live audience "calls" to the audience and the audience responds. It's a tradition brought to the US by West African slaves and can be seen in sermons by evangelical Baptist preachers and in rock concerts. If you've been to one of these participatory, interactive events, you know that there's something different about being there face-to-face and listending to a concert with earphones or watching a sermon on TV.

Intellectually, oral cultures emphasize dialogue and memory. Socrates, the great philosopher of ancient Greece, is known to us through the "dialogs" of his student Plato, in which Socrates does not make linear arguments but instead engaged in back-and-forth dialog with others in order to make a point. In medieval universities, a lot of the curriculum was devoted to the "memory arts." Scholars at the time could not afford their own hand-copied books, so instead they spent a great deal of time improving their ability to memorize things, sometimes entire books. Stories and arguments were often presented using rhythms, rhymes, and other repeated formulas like daily prayers, which were all aids to memorizing and preserving tradition through time. Many tribal cultures have special elders, who memorize the tradition of the group, often in the form of chants and rhymes, which they then pass on to their successors.

In an oral culture, the spoken word is known to have power. The children's saying "sticks and stones can break my bones, but words can never hurt me," is a very print-culture sentiment. In oral cultures, words carry weight; words can hurt or heal. There are a few contexts in this world where insulting someone's mother is the same as punching them in the nose, contexts where spoken words have force. For example, there's a story of a middle class guy who walks into a working class bar; a few minutes later, he comes sailing back out through the plate-glass window, picks himself up, his nose bleeding, and says, puzzled, "all I did was use words." The middle class guy was living in a print world, but the inhabitants of the bar were, at least at the moment, living in an oral world. In an oral culture, that was the case everywhere.

The Print Revolution

The spread of reading and writing that was made possible by the printing press and widespread literacy is generally acknowledged to have been a central component in the making of the modern world. Writing allows communication between people who are distant from one another; it creates a kind of communication that's necessarily one-way, with little or no interaction. Writing was the first decontextualized communication, disembodied from the immediate experience of another individual. In print culture like ours, where writing becomes omnipresent, communication is impersonal, often anonymous. As a result, in our world, we are in constant relations with people you don't know. The most important evidence in most court cases is written documentation. (That's why they tell you to always save the receipts; it's the piece of paper that matters, not the particular people involved.) This new way of relating has had profound effects.

Science: Print, for example, is said to have made possible the scientific revolution of the 16th and 17th centuries. Before printing, scholars who memorized books or hand-copied them could not reliably share complex tables of numbers about, say, the motions of the planets; it was only when many scholars could share their detailed measurements and experiments through reliably printed books about astronomy that people like Galileo and Newton were able to discover the basic laws of physics.

Individualism: It wasn't until early modern era, with widespread availability of books, that people began to read silently (not reading aloud). This helped establish a general sense of the realm of private experience -- that there is a realm of thinking, feeling, and doing that happens to you as an individual and to no one else. So today, both writing and reading are done alone. Some say this is a key component in the idea that we are all unique individuals, that a person's value in life is not determined by their background but by their inner characteristics.

The Protestant Reformation: In 1379, John Wyclif, an English theologian, attacked the Roman Pope and clergy, arguing that religion was an individual matter, that people did not need priests to tell them the meaning of God. His followers translated the Bible into English (bypassing priests as a route to God). He did this before the advent of the printing press, however, so his Bibles had to be copied out by hand, and his ideas had to spread by word of mouth. He died in 1384, but when a follower (Jan Hus) was burned at the stake in 1415, the Catholic rulers of the day dug up Wyclif's bones and burned them at the same time, just to make a point. Shortly after Gutenberg introduced a printing press into Europe, in 1517, Martin Luther promulgated similar ideas about the church and people's proper relation to God. Luther famously nailed his "95 Theses" to the door of a church, but he also eventually printed them, and went on to print his own Bible in the vernacular. Luther was a great fan of the printing press, and once said, "Print is the best of God's inventions."

The moral is this: Wyclif wanted to promote what were in his day revolutionary ideas, but he could not overcome the monopoly of the Roman Catholic Church because it was so hard to promote alternative thoughts by hand-copied books and word of mouth. Luther had similar ideas, and because he was able to spread those ideas more easily through the printing press, he played a key role in spreading the Protestant revolution throughout Europe. Eventually, through the counter-reformation, even the Catholic Church itself would be forever changed.

Print was just the first of modern, impersonal communication technologies that allowed the widespread dissemination of ideas. Today, print and its successors allow the world to be full of alternative ideas: Karl Marx, George W. Bush, Osama Bin Laden and countless others have all been able to spread their different views through the world only because they have access to modern communication technologies.

Print, in sum, was a media technology that clearly played a key role in ushering in the modern world and revolutionizing human life.

Mobile privatization (from Raymond Williams)

If print changed everything, what about more recent communication technologies? Clearly, some technological shifts have no major effects: the shift from vinyl LP records to CDs, for example, made listening to recorded music less full of static, possible on smaller machines, and a little more expensive; this does not add up to major social change. But what about the telegraph, the radio, movies, or computers?

Cultural critic Raymond Williams coined the term "mobile privatization" to explain one way that communication technologies seem to be playing a role in shaping modern life. Mobile privitazation is a term for describing the day to day nature of new ways of living that have become increasingly common in the last century or so. Mobile privatization is made up of the combination of two trends: increased mobility, and increased privatization.

Mobility

Life has become more mobile, because life is no longer fixed by traditional social ties to the extended family, or by geographical rootedness to a specific place. 150 years ago, even in the US and Europe most people lived on or near farms, in extended families, and they did not move around much on a day to day basis because travel was expensive and difficult; the only way to get around was basically on foot, by horse, or in some cases, by boat. As a result, most Europeans still spent most of their lives living within a few miles of the place where they were born. People's relations with each other were based on traditional social ties: they lived lives rooted in church, family, and tradition. Today, people move around a great deal more than they used to. It's not unusual to commute 40 miles to work and back every day, and in a lifetime commonly travel thousands of miles and often live hundreds or thousands of miles away from their families and place of birth. As a result, life is much more uprooted and more transient than it used to be. Home may be where the heart is, but it's no longer the place you were born.

Increased mobility has some odd effects. One of them is that we now are constantly in contact with strangers, with people we do not know. In a traditional society, loneliness meant being separate from the group, being simply alone. In a mobile society, it's possible to be lonely in a crowd.

Privatization

Life has also become increasingly privatized. People increasingly build their lives in such a way that they cut themselves off from the people immediately around them. We put fences and hedges around our houses, live in apartments where we do not know our immediate neighbors and don't care to, and we highly value the ability to separate ourselves off from the others around us. (College students living in dorms are actually one of the few social situations left where things are not particularly privatized; students constantly mix work and play, and their lives intermingle with others more freely than at almost any other time in life.) As adults out of college, when we leave work and "go home," we like to go to a place where we can shut the door behind us and not be in contact with anyone but our family or best friends. Perhaps in response to the uprooted quality of our highly mobile lives, we have created new forms of private world: the domestic space. People make sharp divisions in their lives between the public and private, and carefully create a quiet private space for themselves away from work. This private space is often the home, the domestic scene.

Private spaces are also the place where most radios and TVs are principally used.

Mobility and privatization combined

In mobile privatization, these two trends are combined. The general feeling of mobile privatization is captured in things like the car: a car comprises a private, sealed-off world for someone, but it's also highly mobile, you can take it anywhere you want. When we go for a drive without planning to go anywhere in particular, we often are doing so to "get away" into our own, personal, mobile privatized space. (RV's, which are essentially houses on wheels, take mobile privatization to one of its logical extremes.) Mobile privatization is also expressed in the use of a personal music player: with a Walkman or an iPod, you surround yourself with your own music, shut out the world in a sense, and create your own private space -- a space you can carry around with you wherever you go, like a bubble; it's mobile and it's privatized.

The Connection Between Media And Mobile Privatization

Contemporary media play two intertwined roles here: they fit into mobile privatized lifestyles by bringing culture and information into privatized spaces -- the newspaper delivered to your door, the TV set in the living room, the radio in your car -- but media also in various ways encourage mobile privatization: the shows and ads on our radios and TVs tend to encourage a mobile privatized way of life by encouraging us to buy products and engage in activities suitable for our privatized homes, cars, etc. Radios, TVs, and magazines sell more radios, TVs, and magazines.