Wisconsin

Number

of Victims

There were a total of 1,823 people on record who were sterilized

(Paul, p. 546). Of those whom were sterilized, 79% were women and 99.5% were deemed mentally deficient.

The state passed its first

sterilization law in 1913, but sterilizations did not occur until 1915,

when the first 76 were conducted at the Northern Wisconsin Center for

the Developmentally Disabled (Goc, p. 40). Legal sterilizations

continued in Wisconsin until 1963 (Paul, 546).

Temporal Pattern of Sterilizations and Rate of Sterilization

While a

relatively small number of people were

sterilized through the late 1920s, the number of sterilizations

increased in

the 1930s and remained high until the end of World War II. For this period, the

average number of

sterilizations was about 80 per year. There were approximately 3 sterilizations per 100,000 people per year.

Passage of Law(s)

On July 30,

1913 (Dowbiggin, p. 126), Governor Francis

McGovern of

Groups Identified in the Law

Groups specifically identified by the 1913 sterilization law are inmates of both mental and penal institutions (Laughlin, p. 12; Painter): “criminals, insane, feeble-minded, and epileptics” (“Health-Marriage and Sterilization Acts”). Although these were specifically enumerated, those who were most likely to be sterilized were feebleminded people (mostly women) who were deemed to be sexually promiscuous (Paul, p. 548).

Process of the

Law

Although the sterilization process is not detailed explicitly in the law and it contains no “procedural safeguards” (Paul, p. 540), the examining board did have to make a unanimous decision that sterilization was in the best interest of the individual and society as a whole (Laughlin, p. 12); they also had to agree that it was the “safest and most effective” way of curtailing the patient’s ability to reproduce (Painter, 2001). After reports suggesting certain sterilizations were filed to the institution’s superintendant, that superintendant then had to make a recommendation to the Department of Public Welfare. Subsequent to this action, a panel of experts (a surgeon and a scientist) would review the case and then begin ascertaining the consent of the person in question. If consent was refused, the patient would not be forcibly sterilized; they would be kept institutionalized indefinitely (Paul, p. 542). Once sterilization was conformed, women received salpingectomies, whereas vasectomies were performed on male patients (Brown, p. 31). The law also restricted the amount of money that could be spent on sterilizations to two thousand dollars per year (Laughlin, p. 12).

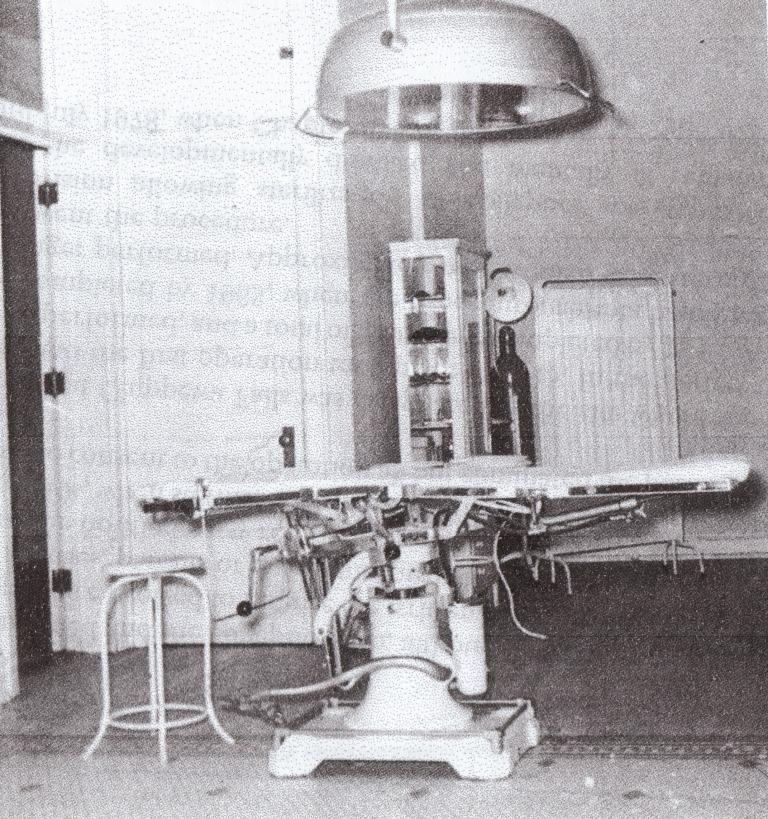

(The

operating table at the Northern Wisconsin Center for the

Developmentally Disabled where sterilizations were performed. Photo

origin: Goc, p. 40).

(The

operating table at the Northern Wisconsin Center for the

Developmentally Disabled where sterilizations were performed. Photo

origin: Goc, p. 40).

Precipitating Factors and Processes

The

movement began in the 1890s, when progressive

“educators, charity and correction officials” began looking for ways to

solve

the economic crisis they were facing (Dowbiggin, p. 125). In response to this in

1895 the state passed

legislation to build a “Home for the Feeble-Minded” at Chippewa Falls,

where

“idiot” children could be placed, reproduction of epileptic and

feeble-minded

women curtailed, and “imbeciles” educated to their highest potential

(Wisconsin

Department of Health Services, 2007).

The establishment of this center was popular with

progressive state

reformers because they believed that “custodialism” would help prevent

“defectives” from reproducing (Dowbiggin, p. 125).

These homes were well-liked but the fact that

they were overcrowded and expensive led to the increasing

attractiveness of

sterilization (Vecoli, p. 195). A

primary factor leading to the initial institution of the 1913

sterilization law

was that

Although the law specifically listed several groups for sterilizations (Painter), those who were targeted in practice were primarily “feebleminded” because they were actually at risk of procreating. However, severely disabled persons were more likely to be institutionalized with long term care for their entire lives and therefore were less considered for sterilizations, particularly because they were less likely to reproduce. Thus, a target was placed on those with lower levels of disability. Furthermore, sexually promiscuous people would be most likely to reproduce and therefore would be targeted the most (Paul, p. 548). Because of the nature in which society and legislators viewed promiscuity, women were more likely to be labeled as such than men and the impoverished lower class was more likely to be targeted than the middle and upper classes (Paul, p. 546).

In 1907

Albert

Wilmarth moved to Wisconsin from

Pennsylvania. He

was the first director

of the Home for the Feeble-Minded in

(Photo origin: American Sociological Association; available at http://www2.asanet.org/governance/ross.html).

(Photo origin: American Sociological Association; available at http://www2.asanet.org/governance/ross.html).

Edward A.

Ross (1866-1951) was a professor of sociology at the

Dr. Richard Dewey,

additionally, was the head physician of Milwaukee Hospital for the

Insane and was also mentioned as an advocate of sterilization in

Wisconsin, despite the fact that no sterilizations were reported at

this institution (Robison, p. 275).

(Photo origin: Waymarking.com, available at http://www.waymarking.com/waymarks/WM1KA4)

(Photo origin: Waymarking.com, available at http://www.waymarking.com/waymarks/WM1KA4)

The

Wisconsin Home for the Feeble-Minded was founded in 1897 in Chippewa

Falls. The name of the institution changed several times, including in

1922, when it was renamed the Northern Wisconsin Colony and Training

School. As of 1976, it is known as the Northern

Wisconsin Center for

the Developmentally Disabled

(Photo origin: Wisconsin Department of Health Services; available at http://dhs.wisconsin.gov/mh_winnebago/WMHI_Museum.htm)

(Photo origin: Wisconsin Department of Health Services; available at http://dhs.wisconsin.gov/mh_winnebago/WMHI_Museum.htm)

The Wisconsin Hospital for the Insane was known as the Winnebago Mental Health Institute in Winnebago, Wisconsin and is still used for psychiatric and behavioral care (Wisconsin Department of Health Services 2011). In 1973, the Julaine Farrow Museum was established to display the history of the Winnebago Mental Health Institute. Despite that Farrow authored an entire history of the institution, of which she was considered the “official hospital historian,” there is no mention of the institutions history of sterilization (Farrow, p. 325). Sterilization also goes unmentioned in the two histories published by the institution itself, which collectively cover the institution from 1873 to 1998 (Winnebago Mental Health Institute). Its website also fails to mention its relationship with eugenics (Wisconsin Department of Health Services 2008).

The

Catholic community of

Chamberlin, Thomas C. 1919. Biographical Memoir Charles Richard Van Hise. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office.

“Doctor Ridicules Laws for Eugenics.” 1914. The New York Times (June 21).

Dowbiggin, Ian R. 1997. Keeping

“Eugenics Law is Declared Invalid.” 1914. The New York Times (January 14).

Farrow, Julaine. 2008. An Asylum's Journey: Healing Through the Centuries: The History of Winnebago Mental Health Institute, 1873-1998. Winnebago, WI: Winnebago Mental Health Institute.

Goc, Michael, ed. 1997. Island of Refuge: Northern Wisconsin Center for the Developmentally Disabled, 1897-1997. Friendship, WI: New Past Press.

“Health-Marriage and Sterilization Acts are Adopted.” 1913. The New York Times. July 26.

Hertzler, Joyce O. 1951. “Edward Alsworth Ross: Sociological Pioneer and Interpreter.” American Sociological Review 16, 5: 597-612.

Laughlin, Harry H. 1922. Eugenical Sterilization in the

Lombardo, Paul. 2008. Three Generations, No Imbeciles.

Lucey, Patrick J. 1997. Wisconsin Women and the Law: The Governor's Commission on the Status of Women. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Painter, G. 2001. “The Sensibilities of Our Forefathers; The History of Sodomy Laws in the Unites States.” Available at <http://www.glapn.org/sodomylaws/sensibilities/wisconsin.htm>.

Paul, Julius. 1965. "'Three Generations of Imbeciles Are Enough': State Eugenic Sterilization Laws in American Thought and Practice." Unpublished ms. Washington, D.C.: Walter Reed Army Institute of Research.

Robinson, Dale W. 1980. Wisconsin and the Mentally Ill. New York: Arno Press.

Vecoli, Rudolph J. 1960. “Sterilization: A Progressive Measure?” Wisconsin Magazine of History 43: 190-202.

Wisconsin Department of Health Services. 2007. “History of Northern Wisconsin Center.” Available at <http://dhs.wisconsin.gov/dd_nwc/aboutnwc/history.htm>.

Wisconsin Department of Health Services. 2008. “Winnebago Mental Health Institute.” Available at <http://dhs.wisconsin.gov/mh_winnebago/HISTORY.HTM>

Wisconsin Department of Health Services. 2011. “Winnebago Mental Health Institute.” Available at <http://www.dhs.wisconsin.gov/mh_winnebago/INDEX.HTM>