Washington

Number of Victims

685 people were sterilized in the state of Washington under the 1921 law (Talkingsticktv, "Interview: Joanne Woiak"; Paul, p. 530). 501 of those sterilized were women and the remaining 148 were men. Therefore, almost 75% of the victims were women. The majority of the sterilizations were performed on people deemed mentally ill (256 women and 147 men) or mentally deficient (243 women and 33 men). A small number of rapists or habitual criminals also appear to have been sterilized. Recordkeeping for these sterilizations was not very reliable and it is likely that many more people were sterilized than can be dependably determined (Talkingsticktv, "Interview: Joanne Woiak").Period During Which Sterilizations Occurred

Washington had two different sterilization laws. The first was passed in 1909 and allowed for the sterilization of any person who was “guilty of carnal abuse of a female person under the age of ten years, or of rape” and of habitual criminals. Very few sterilization operations were performed under this law. A broader sterilization law was passed in Washington in 1921 and sterilizations occurred beginning with the passage of that law through the year 1942. The final sterilization took place by 1942 when the 1921 sterilization law was declared unconstitutional (Paul, pp. 525-528).

Temporal Pattern of Sterilizations and Rate of Sterilization

Passage of Laws

Washington was the second state to pass a sterilization law. The first law was passed in 1909. It was punitive in nature and referred only to habitual criminals and those who were convicted of rape, for whom sterilization would be a punishment (Laughlin, p. 6; Landman, p. 56). The 1909 law was challenged and upheld in 1912 in the case of State v. Feilen (Fenning, p. 806; Laughlin, p. 149). Peter Feilen was convicted with the rape of a female under the age of ten on September 30, 1911. Feilen was given a life sentence and ordered to have an operation for the “prevention of procreation” (Mosby, p. 118). The defendant appealed on the claim that sterilization for criminals was cruel and unusual punishment. Nevertheless, the Washington Supreme Court found that it could not qualify as cruel and unusual because “the operation of vasectomy is a very simple one” (Fenning, p. 806). What should be considered is that “ it seems very clear from a careful reading of the decision that the court confined its interpretation of cruelty to the actual physical pain incident at the time of the operation” (Fenning, p. 806). The Feilen case was the “first time a sterilization statute had been challenged in a high court” in the U.S. (Talkingsticktv, “Talk: Joanne Woiak”). The 1909 sterilization law is still on the books as of March 2011 (Washington State Legislature, “RCW 9.92;” Washington State Legislature, "RCW 9.92.100;” Talkingsticktv, "Interview: Joanne Woiak"). It is in the Revised Code of Washington in Title 9 and is listed under two categories: Crimes and Punishments (Washington State Legislature, "RCW 9.92) and Prevention of Procreation (Washington State Legislature, "RCW 9.92.100"). However, the law appears to be used very rarely (Talkingsticktv, "Interview: Joanne Woiak"; Paul, p. 528).A bill was introduced in January of 1915 that aimed to sterilize every patient in Washington mental hospitals and the state institution for the feeble-minded. If the superintendent of the institution decided that an individual “would produce children with an inherited tendency to crime, insanity, feeble-mindedness, idiocy, or imbecility, and there is no probability that the condition of such person will improve to such an extent as to render procreation by such person advisable,” the patients would not be discharged unless they were sterilized or they won an appeal to this decision in the Superior Court (Rucker, p. 221).

A more comprehensive law was passed in 1921. This law included a much broader group in state institutions (see below) and was in place until 1942, when it was invalidated (Paul, pp. 525-526).

In 1912 law was repealed in 1942 in the Hendrickson case on the grounds that there was not due process of law for the individuals being sterilized (Talkingsticktv, “Talk: Joanne Woiak"; Paul, p. 526). However, the judges in the case continued to support the concept of sterilization, just not the unconstitutional way it was being carried out.

The 1909 law was aimed only at habitual criminals and those who had committed crimes of rape and sexual abuse of a female younger than ten years old (Paul, p. 525). The 1921 law identified those who were in institutions and “feebleminded, insane, epileptic, habitual criminals, moral degenerates, and sexual perverts” (Laughlin, p. 6; Landman, p. 56; see also Paul, p. 526).

Process of the Law

Under the 1921 law, inmates in

state institutions could be selected and have their cases examined by

the Board of Health, subsequent to superintendents of state

institutions having given quarterly reports about those who could be

candidates for sterilization (Landman, p. 56). Those approved by the

Board of Health could be sterilized, with a notification prior to the

operation. Individuals had fifteen days to protest the ruling and no

sterilization could be carried out while the protest was being

reviewed. As soon as an order from the superintendent of the Board of

Health was received, sterilization could be carried out (Laughlin, pp.

16-17).

Groups Targeted and Victimized

People who were targeted were often those who were

deemed socially degenerate. These included “reform-school girls,

welfare moms, the retarded, gays, and the physically disabled”

(Berger). Many homosexuals who faced imprisonment also faced

sterilization under the 1909 law (Boag, p. 207).

There

was an

element of race inherent to the practice of sterilization.

Washington “heartily embraced the association between illegitimacy,

mental incompetence, and poverty among black women” (Kluchin, p.

92). Kluchin claims that Washington even sterilized one black

woman twice. The woman underwent a tubal ligation surgery at

fifteen years old after her first pregnancy, but the operation was

unsuccessful. The state forced her to have both a hysterectomy

and an abortion when she became pregnant a second time at nineteen

years old (Kluchin, p. 92).

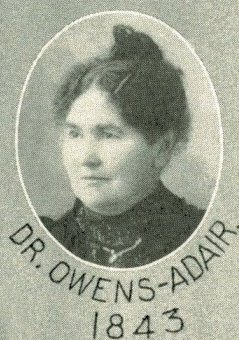

Bethenia Owens-Adair was a physician and avid supporter of eugenics throughout the Northwest. She advocated sterilization as a form of punishment, as it was used in the 1909 sterilization law (Boag, p. 207; see Oregon for more information).

Source: http://www.oregonpioneers.com/graphics/Dr.Owens-Adair_1843.jpg

Source: http://www.oregonpioneers.com/graphics/Dr.Owens-Adair_1843.jpg

Many activists supporting sterilization laws were

Progressive women who lobbied on behalf of the 1921 law (Brown et al.).

“Feeder Institutions” and Institutions Where Sterilizations Were Performed

According to the currently available information, all individuals who were sterilized were those living in state institutions (Laughlin, p. 15). Washington State Penitentiary at Walla Walla and the State Reformatory at Monroe were prisons in which a small number of prisoners were chosen for sterilization (Laughlin, p. 91). Some institutions cannot be determined with certainty, but the state psychiatric hospitals are likely locations where sterilizations were performed (Brown et al.; Foster, p. 6187). Goldsmith/Reed’s report of Washington’s state institutions of 1912 identifies the above state prisons as well as two state asylums for those with mental illness, state schools for the deaf and the blind, and two places for those deemed mentally deficient and/or deviant: the State Institution for the Feeble-Minded at Medical Lake, and the State Training School at Chehalis.State Training School at Chehalis

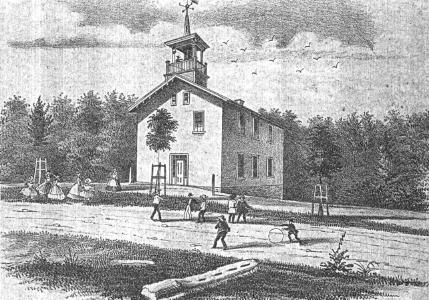

This institution opened on June 10, 1891 as “The Washington State Reform School” (also known as the State Training School at Chehalis), but its name changed a couple times. After being called “Washington State Reform School” it was renamed “Washington State Training School” in 1907, and finally, “Green Hill Academy.” It began as a “school for youth ages 8 to 18 who commit[ted] crimes or are orphaned” (Ott). It was an agricultural school and its inmates were required to work. The land that was used to farm was eradicated when Interstate 5 was built, but the inmates continued to labor at other tasks such as doing carpentry work and repairing automobiles ("Fast Times as Green Hill High," "Two New Buildings at State Training School"). The school was overcrowded by 1911 and healthy food was a luxury for inmates “Severe corporal punishment was the norm” (Washington State Department, "A History of Human Services"). It began as a coed institution and the females apparently did not live in better conditions than the males. “The girls' dormitory was in a wooden building with no fire escapes. Girls were locked in the dormitory without any supervision from 8 p.m. until 6:30 a.m. In order to ensure that girls and boys did not mix, girls were never allowed to go outdoors” (Washington State Department, "A History of Human Services"). In 1913 a separate school was made for girls only, called the Maple Lane School. The Washington State Training School continues to operate under the name “Green Hill School” and is run by the Juvenile Rehabilitation Administration. Green Hill is now solely an institution for youth who commit crimes. It does not accept young children any longer. The school’s original stated aims have not changed and it continues to educate and reform male youth (Washington State Department, "A History of Human Services").

Source: http://freepages.genealogy.rootsweb.ancestry.com/%7Epaxson/graphics-pax/greenhill_school.jpg

Source: http://freepages.genealogy.rootsweb.ancestry.com/%7Epaxson/graphics-pax/greenhill_school.jpgMaple Lane School

The Maple Lane School was officially opened on December 22, 1914 in Grand Mound, Washington as an offshoot of the State Training School at Chehalis. It was originally named the “State Training School for Girls” (changed to Maple Lane School in 1959) and was for delinquent girls. In 1951 the school’s purpose evolved from mainly trying to punish girls to trying to help them (“History of Maple Lane High School”). The Maple Lane School later functioned as an institution to treat and educate male offenders, “typically [. . .] with various mental health or cognitive functioning issues, in addition to chemical dependency and/or sex offending treatment needs” (Washington State Department, "Institutions"). In 2010 there was a section in Washington’s state operating budget that, if passed, would allow the closure of Maple Lane (Schrader). The legislation was passed in 2011 and the closure set for June of 2013, but the current governor of Washington, Chris Gregoire, expedited the closure to June of 2011 (Allen).

(Photo origin: Maple Lane High School, available at http://www.rochester.wednet.edu/MLHS/history.htm)

(Photo origin: Maple Lane High School, available at http://www.rochester.wednet.edu/MLHS/history.htm)

State Institution for the Feeble Minded

The

State Institution for the Feeble Minded was opened in 1905 near Medical

Lake and had a capacity of 600 beds (Haber, p. 223; Remington, p.

1499). It was

established to help the overcrowding situation at other mental

institutions and was meant to serve individuals with “more severe

mental retardation,” both male and female. However, this

institution would only care for people through age twenty-one and would

discontinue care afterwards except under certain circumstances

(Washington State Department, “A

History of Human Services;” Remington, p. 1501). The school

district

clerks were to report all children who were “feeble-minded” or

“defective” to this institution (Remington, p. 1500). The State

Institution for the Feeble-Minded at Medical Lake changed its name to

[Eastern State] Custodial School in 1933, subsequently renamed Lakeland Village. Lakeland Village operates

today as a provider of services for developmentally disabled persons

(Washington State Department, “Lakeland”).

Woiak ("Public History") presents evidence that at this institution eugenic sterilizations were performed.

Due to overcrowding, a second custodial school [Western State Custodial School] was opened in Buckley, subsequently renamed Rainier State School (Washington State Department, “A History of Human Services”).

Woiak ("Public History") presents evidence that at this institution served as a "feeder institution" for eugenic sterilization. (Photo origin: Lakeland Village, available at http://www1.dshs.wa.gov/DDD/lakeland.shtml)

(Photo origin: Lakeland Village, available at http://www1.dshs.wa.gov/DDD/lakeland.shtml)

Western State Hospital opened in 1871 as the “Insane Asylum of Washington Territory.” It is located at Fort Steilacoom, which was a military post from 1849 to 1868 and was purchased by the Washington Territory in order to build an insane asylum (Roberts; Washington State Department, “What is Western State Hospital?"). Patient neglect was very prominent between 1871 and 1875 because a local businessman was running the hospital. The hospital was renamed Western State Hospital in 1889 when Washington became a state. The hospital is still functioning today, but is currently treating patients using “psychotropic drugs, counseling, and behavior modification therapies” instead of the older practices that had been used. It is one of the two state-owned adult psychiatric hospitals and “provides evaluation and inpatient treatment for individuals with serious or long-term mental illness that have been referred to the hospital through the Regional Support Network system” and “serves the needs of western Washington for all individuals who have been committed as a result of a criminal proceeding” (Washington State Department, “What is Western State Hospital?”).

Woiak ("Public History") presents evidence that at this institution eugenic sterilizations were performed.

(Photo

origin: Western State Hospital, available at

http://bipolar-stanscroniclesandnarritive.blogspot.com/2010/07/western-state-hospital-washington.html)

(Photo

origin: Western State Hospital, available at

http://bipolar-stanscroniclesandnarritive.blogspot.com/2010/07/western-state-hospital-washington.html)Eastern State Hospital

Eastern State Hospital, located at Medical Lake, was a psychiatric hospital opened in March of 1891 to alleviate the serious overcrowding at Western State Hospital (Wikipedia). It functioned as a mental hospital (Washington State Department, “A History of Human Services”). “Feebleminded and epileptic persons acquitted of crime by reason of mental irresponsibility” were sent to the “criminal insane department” here. The hospital currently still specializes in treating mental disorders, but its standards of care are much better than in the past (Haber, p. 223).

(Photo origin: Eastern State Hospital, available at http://www.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~asylums/medlake_wa/index.html)

(Photo origin: Eastern State Hospital, available at http://www.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~asylums/medlake_wa/index.html)Northern State Hospital

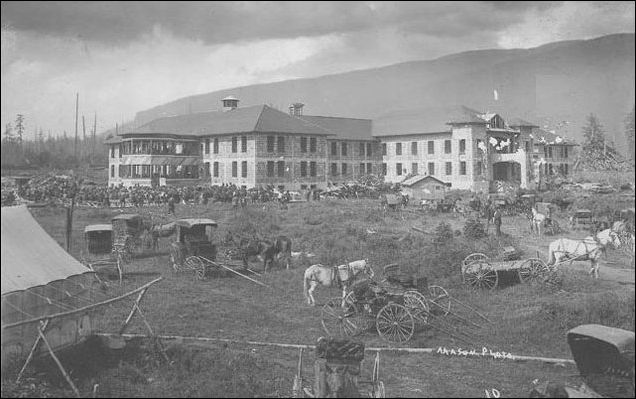

Northern State Hospital was a psychiatric facility constructed in 1909 in Sedro-Woolley. It was built to take some of the burden of the overcrowding at the Western and Eastern State Hospitals and was meant to be a completely self-sustaining institution (Bourasaw; Davis, p. 238). It included housing, facilities, and livestock and agricultural operations. The Olmstead brothers designed the campus (“Northern State Hospital”). The hospital opened to patients in December of 1912 (Bourasaw; Davis, p. 238). The patients here were “treated” with physical labor, lobotomy, electroshock therapy, and sterilization (Davis, p. 238). In 1973, the hospital closed its doors and some of the complex was converted for use for Job Corps and a drug treatment center (Davis, p. 241). After that, the main buildings became the North Cascades Gateway Center, but the outbuildings were not being used for another purpose. The agricultural area was converted into the Northern State Recreation Area (“Northern State Hospital;” Read). On December 20, 2010 the Hospital was listed in the National Register of Historic Places because of its “connection to the broad patterns of institutionalizing the mentally ill at the turn of the 20th century as expressed in the Pacific Northwest.” The listed area was on the market for seventeen million dollars as of March 16, 2011 because of a budget shortfall in Washington state (“Northern State Hospital Listed in the National Register of Historic Places”).

Woiak ("Public History") presents evidence that at this institution eugenic sterilizations were performed.

(Photo origin: Northern State Hospital, available at http://www.skagitriverjournal.com/NearbyS-W/NSH/NSH1-Intro.html)

(Photo origin: Northern State Hospital, available at http://www.skagitriverjournal.com/NearbyS-W/NSH/NSH1-Intro.html)Notes

For a quick and accurate overview of eugenics in the U.S. and Washington state, see Joanne Woiak, professor in the Disabilities Studies Program, University of Washington in the Disability Studies Program: <http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s86CCiSAuI8>

<http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f204e9VtXfk>. A conference held on October 9, 2009 on the subject of eugenics can be viewed here: http://depts.washington.edu/disstud/eugenics-and-disability/symposium/proceedings

Bibliography

Allen, Marquise. 2011. “Grand Mound: Effort to Save Juvenile Facility Dealt Setbacks.” The News Tribune. January 26. Available at: <http://www.thenewstribune.com/2011/01/26/1517741/grand-mound-effort-to-save-juvenile.html>.

Berger, Knute. 2003. "Breed and Weed." Seattle Weekly (April 16). Available at: <http://www.seattleweekly.com/2003-04-16/news/breed-and-weed.php/>.

Boag, Peter. 2003. Same-sex Affairs: Constructing and Controlling Homosexuality in the Pacific Northwest. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Bourasaw, Noel V. 2003. “History of Northern State Hospital, of Sedro-Woolley, Washington Part 1: Introduction and Overview.” Skagit River Journal. Available at: <http://www.skagitriverjournal.com/NearbyS-W/NSH/NSH1-Intro.html>.

Brown, Sherrie, et al. 2008. “Powerpoint Presentation.” Course on Disability and Society: Introduction to Disability Studies, Fall 2008, University of Washington. Available at: <http://courses.washington.edu/intro2ds/Lecture%20materials/Woiak-May15-eugenics--2.PPT>.

Cultural Landscape Foundation. 2009. “Northern State Hospital.” 16 October. Available at: <http://tclf.org/landslides/northern-state-hospital>.

Cultural Landscape Foundation. 2011. “Northern State Hospital Listed in the National Register of Historic Places.” 16 March. Available at: <http://tclf.org/node/6217>.

Davis, Jeff, and Al. Eufrasio. 2008. Weird Washington. New York: Sterling Publishing.

“Fast Times as Green Hill High.” Crimson & Gray Online. Available at: <http://www.localaccess.com/wfwc/issue14/greenhill.htm>.

Fenning, Frederick A. 1913. "Sterilization Laws from a Legal Standpoint." Journal of the American Institute of Criminal Law and Criminology. May, vol. IV, pp. 802-14. Available at: <http://books.google.com/books?id=1uAtAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA805&dq=sterilization+washington+state&hl=en&ei=fnNsTaf-N4WTtweR_5XsBQ&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=4&ved=0CDsQ6AEwAzgK#v=onepage&q=sterilization%20washington%20state&f=false>.

Foster, Ellsworth D., Locke, George Herbert, O’Shea, and Michael Vincent. 1918. “Washington.” The World Book: Organized Knowledge in Story and Picture, Vol. 8. Chicago: Hanson-Roach-Fowler Company. 6187. Available at: <http://books.google.com/books?id=OwIEAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA6187&lpg=PA6187&dq=state+institution+for+the+feebleminded+at+medical+lake&source=bl&ots=7nNZHR4kbG&sig=C3PxcQ48tl5j51fvF57W46cWNjA&hl=en&ei=EnCLTbnGJIXp0gH84rSEDg&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=2&ved#v=onepage&q=chehalis&f=false>.

Goldsmith, May; and Anna Reed. 1912. Report of Conditions in the State Institutions of Washington. Olympia: Boardman.

Haber, Roy, and Hamilton, Samuel Warren. 1917. “Washington.” Summaries of State Laws Relating to the Feebleminded and the Epileptic. New York: The National Committee for Mental Hygiene. Available at: <http://books.google.com/books?id=Q_7SAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA223&lpg=PA223&dq=state+institution+for+the+feebleminded+at+medical+lake&source=bl&ots=bzVbTX32qH&sig=eTqDOrfh8bxVLoJiEx9DQkvP29Y&hl=en&ei=gG6LTdHRB6TH0QGEnJH5DQ&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=2&ved=0CBwQ6AEwAQ#v=onepage&q=medical%20lake&f=false>.

Justia Law.com. “2005 Washington Revised Code RCW 9.92.100: Prevention of Procreation.” Available at: <http://law.justia.com/codes/washington/2005/title9/9.92.100.html>.

Kluchin, Rebecca Marie. 2009. Fit to be Tied: Sterilization and Reproductive Rights in America, 1950-1980. Piscataway, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Landman, J.H. 1932. Human Sterilization: The History of the Sexual Sterilization Movement. New York: MacMillan.

Laughlin, Harry H. 1922. Eugenical Sterilization in the United States. Chicago: Psychopathic Laboratory of the Municipal Court of Chicago.

Maple Lane High School. “History of Maple Lane High School.” Available at: <http://169.204.153.54/MLHS/history.htm>.

Mosby, Thomas Speed. 1913. Causes and Cures of Crime. St. Louis: C.V. Mosby. Available at: <http://books.google.com/books?id=xyEOAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA118&lpg=PA118&dq=thomas+speed+mosby+feilen+case&source=bl&ots=PQx8C94471&sig=1Q1nAkTblVUm_Gq5Vl7wKVzhChc&hl=en&ei=NDyCTf7TM4XagAfRgY3dCA&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CBUQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q&f=false>.

Ott, Jen. 2008 “Washington State Reform School opens in Chehalis on June 10, 1891.” HistoryLink.org. Available at: <http://www.historylink.org/index.cfm?DisplayPage=output.cfm&file_id=8647>

Paul, Julius. 1965. "'Three Generations of Imbeciles Are Enough': State Eugenic Sterilization Laws in American Thought and Practice." Washington, D.C.: Walter Reed Army Institute of Research. 525-530.

Read, Tom. 1973. “Northern State Hospital Closes Part 4: The Death Throes, 1973.” Skagit River Journal. 6 May 1973. Available at: <http://www.stumpranchonline.com/skagitjournal/S-WArea/NSH/NSH4-ClosingTime1.html>.

Remington, Arthur, Washington State. 1916. Remington’s Codes and Statutes of Washington. San Francisco: Rancroft-Whitney. Available at: <http://books.google.com/books?id=vTcbAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA1499&lpg=PA1499&dq=state+institution+for+the+feebleminded+at+medical+lake&source=bl&ots=TW30VN1dZH&sig=IqHMGHq2kUDFGopG8_a3aiZ-akg&hl=en&ei=gG6LTdHRB6TH0QGEnJH5DQ&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=7&ved=0CDUQ6AEwBg#v=onepage&q&f=false>.

Roberts, Andrew. “A Middlesex University Resource.” Studymore.org. Available at: <http://studymore.org.uk/america.htm>.

Rucker, W.C. 1915. "More 'Eugenic Laws.'" The Journal of Heredity. vol. VI, pp. 219-226. Available at: <http://books.google.com/books?id=Om9uLuAYbOwC&pg=PA221&dq=sterilization+washington+state&hl=en&ei=B2xsTfK6Doujtgf4veDOBQ&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=4&ved=0CEwQ6AEwAw%23v=onepage&q=sterilization%2520washington%252#v=onepage&q=sterilization%2520washington%252&f=false>.

Schrader, Jordan. 2010. “Protesters Want Veto of Maple Lane School Closure.” The News Tribune. April 30. Available at: <http://blog.thenewstribune.com/politics/2010/04/30/protesters-want-veto-of-maple-lane-school-closure/>.

“Two New Buildings at State Training School Will Be Finished Within Week-Buildings Cost $19,344.” October 16, 1931. Available at: <http://content.wsulibs.wsu.edu/cdm4/item_viewer.php?CISOROOT=/clipping&CISOPTR=24886&CISOBOX=1&REC=6>.

Washington State Legislature. “Chapter 9.92 RCW Punishment.” Available at: <http://apps.leg.wa.gov/RCW/default.aspx?cite=9.92>.

Washington State Legislature. “RCW 9.92.100 Prevention of Procreation.” Available at: <http://apps.leg.wa.gov/RCW/default.aspx?cite=9.92.100>.

Washington State Department of Social and Health Services. “A History of Human Services.” Available at: <http://www.dshs.wa.gov/geninfo/aboutdshs/3history.shtml>.

Washington State Department of Social and Health Services. Division of Developmental Disability. “Lakeland Village.” Available at: <http://www1.dshs.wa.gov/DDD/lakeland.shtml>.

Washington State Department of Social and Health Services. “Institutions.” Available at: <http://www.dshs.wa.gov/jra/institutions.shtml#jra>.

Washington State Department of Social and Health Services. “What is Western State Hospital?” Available at: http://www.dshs.wa.gov/mhsystems/wshfaq.shtml

Wikipedia. “Eastern State Hospital (Washington).” Available at: <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eastern_State_Hospital_%28Washington%29>.

Talkingsticktv. 2010. "Interview: Joanne Woiak-History of Eugenics in Washington State." Oct. 22. YouTube. Available at: <http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f204e9VtXfk&feature=player_embedded>.

Talkingsticktv. 2010. “Talk: Joanne Woiak-History of Eugenics in WA State.” Feb. 4. YouTube. Available at: <http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s86CCiSAuI8>.

Woiak, Joanne. 2009. "The Public History of Eugenics in Washington." Powerpoint Presentation. Available at <http://courses.washington.edu/intro2ds/Lecture materials/A09-Oct27_publichealthgenetics-Woiak.ppt>