***Please note: This web page is part of the larger site "Eugenics: Compulsory Sterilization in 50 American States." A different web site, "Vermont Eugenics: A Documentary History," by Hope Greenberg and Nancy Gallagher, focuses more in eugenics in general and provides many important primary documents.***

Vermont

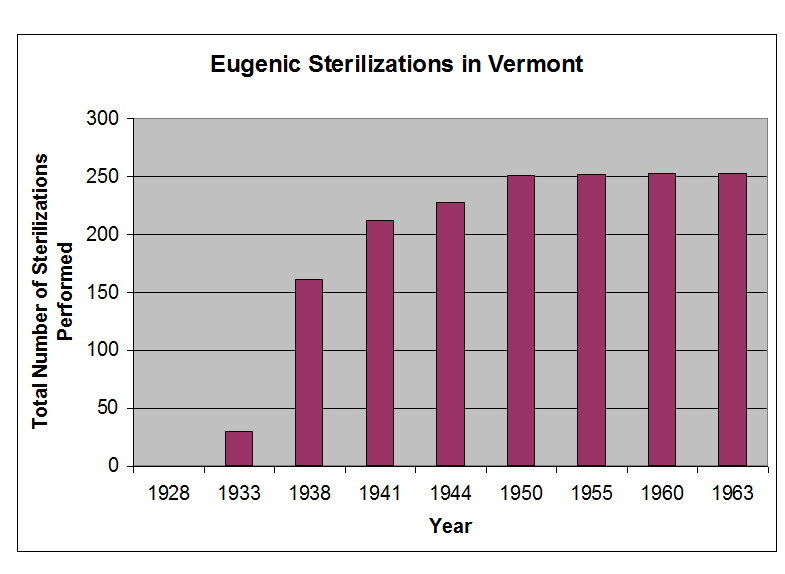

Number of Victims

253 sterilizations were

performed in Vermont making it the 25th

highest in the nation. About two thirds of the total sterilizations

were performed on women. Over 80% of the sterilized were deemed

"mentally deficient."

Period during which sterilizations occurred

The majority of the sterilizations

were

performed in the years 1931-1941, where about 200 people were

sterilized. According to Julius Paul, the last documented

sterilization occurred in 1957 (Paul, p. 494).

Temporal pattern of sterilizations and rate of sterilizations

Nearly all of the sterilizations took place in the first couple of decades of the law’s existence. From 1933-1938, there were 131 sterilizations, or approximately 26 per year; and from 1938-1941, there were about 17 per year. Therefore, the period during which most sterilization occurred was from 1931-1940 where the rate of sterilization was about 6 per 100,000 residents per year.

Passage of Laws

Vermont approved its sterilization law on March 31, 1931 and was the 29th state to pass such a law (Gallagher, pp. 185-186). An earlier law was passed by the legislature in 1913 to target the insane, feeble-minded, rapists, and confirmed criminals but was vetoed by Governor Allen Fletcher on concerns that it would be considered unconstitutional by the courts (Gallagher, p.53, Paul, p. 492). Another attempt at a law was made in 1927, and passed in the Vermont senate, but failed in the house (Gallagher, p. 84).

Groups Identified in the Law

The 1931 law targeted “‘idiots’, ‘imbeciles’, ‘feeble-minded’ or ‘insane’ persons” residing in state institutions (Gallagher, p. 185). This law applied to residents of the state also, not just those institutionalized. “Negative eugenics measures applied to those Vermonters who purportedly had comprised the quality of life for Vermont’s ‘elect’” (Gallagher, p. 133).

Process of the Law

Two physicians attested to the fact that an “idiot, imbecile, feebleminded or insane” person is likely to beget similarly afflicted children. Furthermore, these doctors had to testify that both the patient and society would benefit from the sterilization, and that the operation posed no significant mental or physical risk for the patient. The patient, or a legal guardian if the patient was deemed incompetent to make his/her own decisions, had to request in writing to undergo the operation and had to voluntarily submit to the procedure. If these requirements were fulfilled, it would be legal for a surgeon to sterilize the patient, with vasectomy (cutting the vas deferens) used for men, and a salpingectomy (cutting of the Fallopian tubes) for women (Gallagher, p. 185).

Precipitating Factors and Processes

According to the United States Army’s Draft Board Exams administered to men drafted into the Army in 1917, Vermont had the second highest “defect rate” in the nation (Gallagher, pp. 39-40). Most of these, Public Health Secretary Dr. Charles Dalton argued, could have been prevented if they had been discovered and treated in early childhood. Others wondered if "poor inheritance" had contributed to the apparent "inefficiency" of Vermont's draftees (see Greenberg/Gallagher for further information). At a time when Vermont’s population was stagnant, and agricultural towns seemed to be in decline, and the native Yankee stock was perceived to be replaced by alien French Canadians, such perceptions in the 1920s fed into concerns about Vermont’s backwardness and the decline of a population of a state that prided itself for its self-reliance and ruggedness (Gallagher, pp. 39-45). As part of the agenda of social progressivism, social services were expanded to assist, support, and help educate the disabled, ill, and poor, but this social-scientific approach to social problems also included support for restricting the reproduction of those considered “unfit.”

The Committee on the Care of the Handicapped also fought for the law, arguing that it would allow institutions to turn out patients who wouldn’t threaten the community by bearing more defective children. The law also had added constitutional credibility due to the Buck v. Bell precedent, a U.S. Supreme Court decision (in 1927, shortly after the second failed attempt at a Vermont law) allowing for eugenic sterilization (Gallagher, pp. 122-124).

Beginning in 1922, a course on Eugenics was offered at the University of Vermont, taught by Henry Perkins, which was "recommended...especially ot those interested in any phase of social work, including teaching" (Glenna, p. 290). Another course on eugenics was taught by biology professor Paul Moody in the 60s and 70s (VT Eugenics Survey; available at http://www.uvm.edu/~eugenics/whatisf.html).

Groups Targeted and Victimized

Poor and socially ostracized families were targeted for investigation of the three D’s (delinquency, dependency, and mental defect). These families usually lived “outside the accepted moral or social convention of middleclass America” (Gallagher, p. 37). The three D’s were used to target the poor, the disabled, French-Canadians, and Native Americans. Women were targeted more than men. French-Canadians and Abenakis were seen as a foe and threat to the early colonial settlers of Vermont. They represented “an insidious and continuous invasion” of Vermont and were therefore targeted (Gallagher, p. 45). Studies done on degenerate family lines were often traced back to French Canadian or Native American ancestry and were used to target these groups (Gallagher, pp. 80-82).

Families who were notorious for having illegitimate and/or "defective" children were targeted, as were those notorious for illiteracy, incest, and for having institutionalized family members (Eugenics Survey in Vermont: Studies). Families that had "bad heredity" or mixed racial ancestry were targets of Vermont's Eugenic survey.

Interestingly, as it was historically believed that

the

French had interbred with the Abenaki, the

prejudice

against these two otherwise-disparate groups was in fact linked.

Ten families in total were picked to have a detailed pedigree completed on the family (Eugenics Survey in Vermont: Studies). The “gypsy” family was a prime example. The Vermont Eugenics Survey presented three families as defective, and they stood as paradigmatic for those considered unfit to reproduce: the Gypsy family, with “dark skin” due to African-American, Abenaki, and French Canadian ancestry, the “Chorea family,” whose members suffered from the debilitating medical illness Huntington’s Chorea, and the “Pirate family,” who lived on houseboats on Lake Champlain and also had French-Canadian ancestry (Gallagher, p. 81).

The Abenakis were also a group affected by the

Vermont eugenics program, and while, according to Paul, the last noted

sterilization in Vermont occurred in 1957, between 1973 and 1976, approximately 3,400 Native American women, according to the General Accounting Office, were sterilized in the United States without properly obtainging consent (Dowbiggin, p. 181; see also Forbes 2011).

Major Proponents

(Photo origin: Vermont Eugenics: A Documentary

History, available at http://www.uvm.edu/~eugenics/partnersf.html)

(Photo origin: Vermont Eugenics: A Documentary

History, available at http://www.uvm.edu/~eugenics/partnersf.html)

Henry F. Perkins led the way for the Vermont

eugenics

program. He was born in 1877 in Burlington and grew up two blocks from

the

University of Vermont campus green, where his father was a well known

professor. Perkins was a professor of Zoology at UVM from 1902-1945,

known for his eugenics education. In 1927-28, he took a

sabbatical to solicit funding and organize a comprehensive survey of

rural Vermont, including all aspects of rural life that might explain

the causes and effects of rural decline in the state. What resulted was

the Vermont Commission on Country Life which used eugenic ideas to

develop a plan for community development in the state (see

Greenberg/Gallagher <http://www.uvm.edu/~eugenics/overview2.html>).

Perkins hired the director of the Vermont Commission on Country Life, Henry Taylor, who was a Social Darwinist, Eugenicist and respected scholar (McReynolds, p. 314).

From 1931 to 1934 he was the president of the American Eugenics Society. Here Perkins shared the Eugenics Survey and Vermont Commission on Country Life with a national audience. The survey closed in 1936 and Perkins became director of the Fleming museum until his 1945 retirement (Gallagher, pp. 9-41). Ironically, as Kevin Dann (p. 20) has commented, he, “whose Eugenics survey publications had labeled alcoholism as one of the prominent ‘traits’ of defective Vermont families, spent his last years as a bedridden alcoholic before dying of liver failure in 1956.”

Some of the researchers concluded, to Perkins' disappointment, that mixed race families were not the source of Vermont's degeneracy. Instead they cited teachers who promoted students based on social factors rather than intellectual development and who failed to take into account the physical health of the student in determining mental capacity. More studies related to the ESV can be found at http://www.uvm.edu/~eugenics/studiesf.html.

Perkins still pursued a state eugenical sterilization law, and he understood that public support would be necessary for such a measure. Therefore he implemented a strategy that involved public eugenics education at all levels, hoping that people who understood current eugenical thinking would support the sterilization bills before the legislature.

Vermont's eventual eugenical laws would allow for

segregation in institutions, sterilization, and restrictions on

marriage licenses for those eugenicists deemed "unfit". Over the

course of time, Vermont's sterilization laws have focused on the eugenically

"unfit" (1931), sexual criminals (1967), and persons considered mentally retarded (1987).

For more information about the publicity and policy regarding eugenics

in the state of Vermont see http://www.uvm.edu/~eugenics/publicityf.html.

“Feeder institutions” and institutions where sterilizations were performed

(Photo origin: Vermont Heritige Network,

available at http://www.uvm.edu/~vhnet/hertour/hthome02.html)

(Photo origin: Vermont Heritige Network,

available at http://www.uvm.edu/~vhnet/hertour/hthome02.html)

Brandon School of the Feeble-Minded:

This school was established in 1912 and housed poor,

disabled Vermonters and some who had been sterilized.

When it opened, the available spaces filled

rapidly and had a waiting list in a few years.

“The superintendents of Brandon had difficulty at times

restricting the

use of this facility to those for whom it was intended” (Gallagher, p.

52). It was renamed the Brandon Training School in

1929, and it closed in 1993. It

is

located at 184 Jones Drive in Brandon. For further information, see

Greenberg/Gallagher

(http://www.uvm.edu/~eugenics/vssf.html). Vermont's

Department of

Mental Health's website does not mention past eugenic practices on its

website (http://healthvermont.gov/mh/programs/hospital/index.aspx).

When the school closed in 1993, the state of Vermont tried to market the property, and though bids were made, the land did not sell. Because of the inability to sell the propery, the Dean administration subdivided the school. Peter Holmber, a developer associated with Wake Robin elderly community in Chittenden, agreed in 1997 to gradually acquire the Brandon property. He has plans to renovate three buildings: two for future use as senior housing, and the other for family housing. Also, the McKernon Group and Tubbs Furniture Company bought large chunks of the land to repurpose for industrial uses. As of today, the land had many shops and industries, and some of the buildings are part of the National Register of Historic Places (http://brandon.org/things-to-do/history-the-brandon-museum).

Articles discussing the closing of the institution either barely mention eugenics (Vermont) or do not mention the school's role in eugenics at all (Shoultz). During the public hearing about the deinstitutionalization of Waterbury and Brandon, no mention is made of the institutions' sterilization history (Sorrell).

(Photo origin: Vermont Heritage

Network, available at http://www.uvm.edu/~vhnet/hertour/hthome02.html)

(Photo origin: Vermont Heritage

Network, available at http://www.uvm.edu/~vhnet/hertour/hthome02.html)

Vermont State Hospital for the Insane: The hospital opened in 1891 to house the mentally ill and relieve overcrowding at the Brattleboro Retreat (Kincheloe, pp. 1-2). It was called Vermont State Asylum for the Insane at Waterbury until 1898 when it was renamed Vermont State Hospital for the Insane to reduce confusion between the hospital in Waterbury and the one in Brattleboro (Kincheloe, p. 226). The superintendent of the hospital from 1918-1936, E. A. Stanley, M.D. was a member of the Advisory Committee of the Eugenics Survey of Vermont (Kincheloe, p. 99). The history of the institution contained in Empty Beds mentions that Dr. Stanley was a eugenicist but does not mention the history of sterilizations at the hospital. During the public hearing about the deinstitutionalization of Waterbury and Brandon, no mention is made of the institutions' sterilization history (Sorrell). The Vermont State Hospital continues to operate today. It is located at 103 Main St. Waterbury, Vermont. For further information, see Greenberg/Gallagher [http://www.uvm.edu/~eugenics/vsh.html]. In 2013, records were made available at the Vermont State Archive and Records Administration (http://tinyurl.com/VSH-Records).

Vermont Reform School: The concern over the treatment of juvenile offenders led to the establishment of this school in Vergennes in 1865. It was renamed the Vermont Industrial School in 1898 and the Weeks School in 1937 before it was closed in 1979. Demand for more space led to the creation of the Brandon School (Gallagher, p. 51). For further information, see Greenberg/Gallagher [http://www.uvm.edu/~eugenics/vis.html].

Riverside Reformatory: The reformatory was an institution that housed women, mainly sexual delinquents (adulteresses, prostitutes, and others) in Rutland (Gallagher, pp. 105-106). For further information, see Greenberg/Gallagher [http://www.uvm.edu/~eugenics/rrw.html].

Opposition

There was significant religious opposition from the

Catholic

communities of both the Irish and French Canadians (Gallagher, p. 119). These groups, however, tended to be poor and

disenfranchised and Protestants were politically, socially, and

economically

dominant (Gallagher, pp. 45-46). In 1930, the Casti Connubi (On Christian

Marriage) was

issued by Pope Pius XI. He condemned

eugenics (especially sterilization), marriage based on heredity, and all

forms

of family planning that “interfered with the body’s natural functions”

(Gallagher, p. 119).

There wasn’t a significant amount of protest on eugenics issues by the Vermont population. Vermonters were concerned with the decline of the rural community and the loss of Vermont traditions and values due to the “racial exodus”, the plight of Vermont farmers, and the immigration of French Canadians (Gallagher, p. 123).

Increasing scientific criticism of eugenics was coming out as Vermont implemented its rather late sterilization plan (Gallagher, p. 108). The ideology of eugenics was largely on the defensive in the 1930s as the media gave credence to scientists who criticized sterilization as a tool to steer human evolution (Gallagher, p. 134).

Bibliography

Barna, E. 1997. "Brandon Facility Redeveloped for Mixed Use." Vermont Business Magazine.

Brandon Vermont. Available at <http://brandon.org/things-to-do/history-the brandon-museum>.

Caron, Simone M. 2008. Who Chooses? American Reproductive History Since 1830. Gainesville: University of Florida Press.

Dann, Kevin. 1991. "From

Degeneration to Regeneration: The Eugenics Survey of Vermont,

1925-1936." Vermont

History 59: 5-29.

Dowbiggin, Ian. 2008. The Sterilization Movement. Oxford University Press.

Gallagher, Nancy L. 1999. Breeding Better Vermonters: The Eugenics Project in the Green Mountain State. Hanover: University Press of New England.

Glenna, Leland L., Margaret A. Gollnick, and

Stephen S. Jones. 2007. "Eugenic Opportunity Structures: Teaching

Genetic

Engineering at US Land-Grant Universities since 1911." Social

Studies

of Science 37.2: 281-96.

Greenberg, Hope, and Nancy Gallagher. "Vermont Eugenics: A Documentary History." Available at <http://www.uvm.edu/~eugenics/>

Kincheloe, Marsha R., and Herbert G. Hunt, Jr. 1989. Empty Beds: A History of Vermont State Hospital. Barre, VT: Northlight Studio Press.

McReynolds, Samuel A. 1997. "Eugenics and Rural Development: The Vermont Commission on Country Life's Program for the Future." Agricultural History 71.3: 300-29.

Paul, Julius. 1965. "'Three Generations of Imbeciles Are Enough': State Eugenic Sterilization Laws in American Thought and Practice." Unpublished ms. Washington, D.C.: Walter Reed Army Institute of Research.

Rosen,

Christine. 2004. Preaching

Eugenics. Oxford University Press.

Schuler, Ruth V. 1940. "Some Aspects of Eugenic Marriage Legislation in the United States". The Social Science Review 14.2: 301-316.

Shoultz,

Bonnie. 1999. Closing Brandon

Training School: A Vermont story. Syracuse: Center on Human

Policy, Syracuse University. Available at <http://thechp.syr.edu/brandon.htm>

Sorrell, Esther. 1979. De-Institutionalization of Waterbury and Brandon. Burlington, VT: n.p.

Vermont.

1993. Closing the doors of the

institution, opening the hearts of our communities: Brandon Training

School, 1915-1993.

Waterbury, VT: Vermont Agency of Human Services. Available at:

<http://www.mnddc.org/parallels2/pdf/90s/93/93-CDI-VAS.pdf>