Nebraska

Number of victims

In total, 902 individuals were sterilized in Nebraska, 53% of whom were women. 80% of all people sterilized were deemed “mentally deficient.” Roughly 18% of the total sterilizations were of individuals deemed “mentally ill.” Nebraska ranks 14th in the United States in terms of total number of sterilizations.

Period during which sterilizations took place

Sterilizations began in 1917, two years after the first law was passed. Recorded sterilizations ended in 1963 (Paul, p. 412).

Temporal pattern of sterilization and rate of sterilization

Approximately 42% of all sterilizations (386 individuals) were conducted from 1917 to 1929 (Brown, p. 31). Other than a somewhat higher increase between 1921 and 1929, sterilizations rose relatively steadily until 1941, after which there was a sharp increase until 1944. 79 sterilizations were performed in 1943 alone—a much higher number than pre-1941 sterilizations per year. Between 1941 and 1944, an average of 74 people were sterilized per year, making these years the peak period of sterilizations in Nebraska. During this period, 6 persons per 100,000 Nebraska residents were sterilized per year. After 1944, sterilizations continued at a steady pace until 1963, with the final ten sterilizations occuring in that year.

Passage of law(s)

In Nebraska, the first law regarding sterilization was passed in 1915 after a failed initial attempt by state legislators in 1913 was vetoed by Governor John H. Morehead (Paul, p. 408). This law was passed along with the first civil commitment law, a statute that allowed for involuntary commitment of individuals to the Nebraska Institution for the Feebleminded by the court (Schalock, p. 119). The original sterilization law was revised in both 1929 and 1957 (Paul, p. 409).

Groups identified in the law

The 1915 law provided for the sterilizations of the insane and feeble-minded inmates of state institutions before they were paroled (Landman, p. 74). The state institutions specifically mentioned in the statute included “institutions for the feeble-minded, hospitals for the insane, the penitentiary, reformatory, industrial schools, the industrial home, and other such State institutions” (Laughlin, p. 13).

In 1929, the original law was repealed and a new law was enacted, which included “habitual criminals, moral degenerates, and sexual perverts“—those individuals convicted of rape or incest—as well as the original groups (Landman, p. 75).

The final 1957 amendment of the 1929 law decreased the scope, permitting the sterilizations solely of members of the Beatrice State Home for the "mentally deficient." This alteration thereby exempted the insane and “habitually criminal.” This modification also provides an explanation of the high ratio of "mentally deficient" to mentally ill sterilized, as only the former were housed in the Beatrice State home (Paul, p. 409).

Process of the Law

The first law, passed in 1915, stated that all inmates of state institutions for the feebleminded, as well as inmates of penitentiaries, were lawful candidates for sterilization. If these inmates were going to be discharged, they were made to stand in front of a panel that questioned them on their family history, mental and physical characteristics, and more. If they were found to possess undesirable genetic traits, they were offered a choice: undergo a sterilization procedure and be released into society, or keep their reproductive system intact but stay in the custody of the state (Hered). The consent of the patient or his or her family was necessary in order to proceed with the sterilization (Paul, p. 408).

The 1929 revision of the law made it so that any inmate convicted of rape or other crimes of sexual perversion were to be compulsorily sterilized. Although the sterilization was mandatory for these individuals, the law mandated both notice and hearing and the potential for appeal to the Supreme Court (Paul, p. 409).

The final alteration of the law, in 1957, tightened the scope of the legislation to include only inmates of the Beatrice State Home (Paul, p. 410).

Upholding the Law

One notable case that came out of Nebraska was Cavitt v. State of Nebraska in 1968, where a woman named Gloria Cavitt argued against the need for her to be sterilized in order to apply for parole (Brunius, p. 320). Cavitt, an unwed mother of 8, scored a 71 on her IQ test and was committed to the Beatrice State Home for the Retarded. The superintendent desired to release Cavitt, but required that she be sterilized. Cavitt sued the state, but the Nebraska Supreme Court ruled to uphold the state constitutionality of the already established sterilization law on March 8, 1968. “The order does not require her sterilization. It does provide, in accordance with the statute, that she shall not be released unless she is sterilized. The choice is hers,” emphasized the court (Brunius, p. 321). Cavitt fought back and called for an appeal, but this was denied. However, this decision was met by immense public criticism, which prompted the Nebraska Legislature to repeal the sterilization law (Reilly, p. 149). The legislature added an amendment to this repeal which saved Cavitt from sterilization. It read, "'no sterilization could be done even though a pending Court order indicated otherwise'" (Vose, p. 19). Cavitt was relased from the Beatrice State Home without sterilization, yet the Supreme Court support for sterilization continued to maintain the constitutionality of sterilization in the United States (Reilly, p. 149).

Groups targeted and victimized

Of all of the people sterilized, 423 were men and 479 women, indicating no substantial gender bias in terms of who was sterilized (U.S. Sterilization Statuses). However, between 1915 and 1929, 95 males were sterilized and 291 females were sterilized in Nebraska (Brown, p. 29). In 1923, it was noted that feebleminded women in society are an urgent problem and a “great source of illegitimacy, delinquency, and mental defect” (Schalock, p. 117). This alludes to an early gender bias in Nebraska.

Other groups targeted

In 1929, the Nebraska legislature altered the sterilization law to include those individuals convicted of sodomy. This amendment included individuals who had been deemed “moral degenerates or sexual perverts” (Painter). Additionally, there appears to be no discrimination toward African Americans in Nebraska before 1928, when 4 black inmates were in institutions for the feebleminded compared to 747 whites (Carpenter, p. 66).

Medical procedures

In Nebraska, males underwent vasectomy and females were sterilized via salpingectomy, as opposed to other types of sterilization practiced in other states (Brown, p. 31).

Other issues

In a 1935 legislative act, the State Commission for the Control of Feebleminded Persons was established to prevent the reproduction and marriage of feebleminded persons. The act also required that schools, public agencies, and hospitals identify and report those suspected of feeblemindedness. These names would be sent to agencies that provided marriage licenses. In the case that anyone of these individuals should desire to get married, at least one party in the marriage must be sterilized (Schalock, pps.119-120).

Another interesting eugenic effort took place in 1937, when Unitarian physician Inez Philbrick introduced a euthanasia bill in Nebraska (Dowbiggin, p. 235). The bill was the second attempt in United States History to legalize euthanasia (Dowbiggin, p. 255). However, the effort failed shortly after it was proposed (Dowbiggin, p. 235).

Deception and hiding the facts

Perhaps the most disturbing part about many Nebraskan sterilizations were how under-published they were and that they continue to be unrecognized today. For example, Dr. Elmer A. Thomas wrote an entire history, including the treatments conducted of the Ingleside Hospital for the Insane (later the Hastings Hospital for the Mentally Ill) in 1961, yet in no means was sterilization mentioned (Thomas). In 1931, Superintendent Charlton boasted of his success in releasing patients. He explains ‘Not all of those patients,’ Dr. Charlton explained, ‘were pronounced cured. In fact it is very probable that some of them will of necessity be returned, but their condition was such that I was willing to give them the benefit of the doubt,’” (Thomas, p. 62). This “condition” for release mentioned by Thomas is possibly a result of sterilization. In fact, Harry Laughlin, in Eugenical Sterilization in the United States says that 94 people where considered for sterilization at Ingleside and 13 were sterilized before 1918. Nebraska superintendent W.S. Fast who was instrumental in the development of the institution was quoted by Laughlin saying, “All patients of child-bearing age, otherwise eligible for parole or discharge are passed upon by the Sterilization Board” in February 1921 (Laughlin, p. 78). Thus, the conditions for release in Thomas’ book and in public knowledge are not well known and continue to deceive those who reflect on Nebraska’s history.

Precipitating factors and processes

Popular fears of a state plagued by “social incompetents” were the driving force behind a widespread support of sterilization legislation in Nebraska (Landman, p. 75). This is evidenced by studies, like Shumway’s “Backward and Feebleminded Children in Public Schools,” which included observations of young children throughout Nebraska and addressed the feebleminded crisis facing the state (1915). In the 1918 Biennial Report for the Nebraska Institution for the Feebleminded Youth Administration, Superintendent Griffiths argued that these individuals “cannot be reformed because they do not have the mentality to overcome temptation” (Schalock, p. 117). The state’s declared motive for its sterilization laws was “purely eugenic,” yet some sources also claims that they have a punitive purpose as well (Laughlin, p. 13 and Brown, p. 29).

Feeder institutions and institutions where sterilizations were performed

There were several institutions where sterilization took place. By 1918 the mental hospitals at Lincoln, Norfolk, Ingleside, and Beatrice all performed sterilizations (Laughlin, p. 74).

According to data provided by Julius Paul, more than 80% of sterilizations occurred on residents of the Beatrice State Home (Paul, p. 411), It was founded as the Nebraska Institution for Feebleminded Youth in 1885 in Beatrice, Nebraska (Schalock, p. 14). In 1921, the name was changed to the Nebraska Institution for the Feebleminded along with a new mission statement, which aimed to provide “custodial care and human treatment for those who are feebleminded, to segregate them from society, to study to improve their condition, to classify them, and to furnish such training in industrial mechanics, agriculture, and academic subjects as fitted to acquire” (Schalock, p. 14). By 1935, in order to assure complete separation from society, NIFM resident’s graves were no longer marked with family names, but with numbers; families desired to disassociate themselves from their “defective” relatives by dehumanizing them (Schalock, p. 118). The institution changed its name again in 1942 to the Beatrice State Home, a friendlier title. Sterilizations were confined solely to the Beatrice State Home in 1957. Through the 1960s, three perspectives governed the asylum: education, asylum, and social control. By 1966, 752 residents at the Beatrice facility had been sterilized (Schalock, p. 119). Then, on July 1st, 1975, the Beatrice State Home became the Beatrice State Developmental Center, the name that it holds today (Schalock, p. 19). The Center specializes in the treatment of children and adults with behavioral and developmental disabilities (Nebraska Department of Health, Beatrice). Their webpage has no mention of the location’s past history with sterilization. In September 2006, however, the Beatrice State Developmental Center’s reputation was under fire when inspectors found that there were “serious problems” with the institution, resulting in the transfer of 47 patients from Beatrice to other state institutions in 2009 (Journal Star, 2010, web).

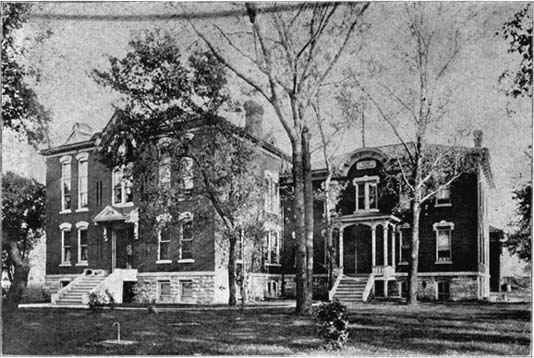

The Hospital for the Incurably Insane was established in 1889. This institution went through several name changes. In 1895, the legislature voted to call it the Asylum for the Chronic Insane. In 1905, the name was changed to Nebraska State Hospital, and then again in 1915 it was renamed the Ingleside Hospital for the Insane. It was briefly referred to as the Hastings State Hospital, and adopted its current name, “Hastings Regional Center,” in 1971 (Adams County Historical Association). Neither the Adams County Historical Society’s website nor Elmer A. Thomas’ history of the institution through 1962 make any mention of the sterilizations that occurred at this location. However, according to Laughlin, 32 sterilizations had occurred at this location prior to 1921 (Laughlin, p. 74). The Hastings Regional Center is currently a mental health and substance abuse treatment facility for adolescent and young adult males who have been paroled from the Youth Rehabilitation Treatment Center in

Kearney, Nebraska (Nebraska Department of Health, Hastings).

(Photo origin: NEGenWeb Project, available at http://www.usgennet.org/usa/ne/topic/resources/OLLibrary/SCHofNE/pics/schn0139.jpg)

The Lincoln Hospital for the Insane was established in 1870, but was only open for a brief period when an accidental fire forced the State to close the facilities for renovations. It re-opened in 1871 (Historic Asylums). According to Paul, 78 sterilizations occurred at this location prior to 1921 (Paul, p. 74). It is now called the Lincoln Regional Center and offers highly specialized psychiatric care to a wide variety of patients (Nebraska Dept of Health, Lincoln). There is no mention of sterilization on the webpage.

(Photo origin: University of Nebrasky-Lincoln, available at http://www.unl.edu/nicpp/images/BSDC1.JPG)

(Photo origin: University of Nebrasky-Lincoln, available at http://www.unl.edu/nicpp/images/BSDC1.JPG)The Norfolk Hospital for the Insane was established as such in 1888 with 97 patients. It maintained its name until 1920, when it became the Norfolk State Hospital and added occupational therapy and recreation activities to its offerings. It is now called the Norfolk Regional Center, though no date has been specified for when this change was made (Schmeckpeper, p 38-39). Again, there is no mention of sterilization on its current webpage.

(Photo origin: Adams County Historical Society, available at http://www.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~asylums/hastings_nb/regional.jpg)

Opposition

Governor John H. Morehead initially vetoed sterilization legislation in 1913, stating that it was “more in keeping with the pagan age than with the teachings of Christianity.” The law passed without his support in 1915, as he did not veto it (Paul, p. 408).

Bibliography

Adams County Historical Society. 2006. “Hastings State Hospital.” Available at <http://www.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~asylums/hastings_nb/index.html>.

Associated Press, The. 2010. “2 More Lawsuits Against Beatrice State Developmental Center.” Journal Star. Available at

<http://journalstar.com/news/local/article_72d3aad4-fb09-11de-99c0-001cc4c03286.html>.

Bruinius, Harry. 2006. Better for All The World: The Secret History of Forced Sterilization and America’s Quest for Racial Purity. New York, NY: Knopf Publishing.

Brown, Frederick W. May 1930. “Eugenic Sterilization in the United States: Its Present Status.” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 149, 3: 22-35.

Carpenter, Niles. Nov. 1928. “Feebleminded and Pauper Negroes in Public Institutions.” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 140, The American Negro: 66.

Dowbiggin, Ian Robert. 2002. “‘A Rational Coalition’: Euthanasia, Eugenics, and Birth Control in America, 1940-1970.” Journal of Policy History 14, 3: 223-260.

Hered, J. 1916. “Nebraska.” The Journal of Heredity 7: 238.

Historic Asylums. (1999). “Lincoln Insane Asylum.” Available at

<http://www.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~asylums/lincoln_ne/index.html>.

Landman, J. H. 1932. Human Sterilization: The History of the Sexual Sterilization Movement. New York: MacMillan.

Laughlin, Harry H. 1922. Eugenical Sterilization in the United States. Chicago: Municipal Court of Chicago.

Nebraska Department of Health and Human Services. 2007. "Beatrice State Developmental Center." Available at <http://www.dhhs.ne.gov/dip/ded/bsdcindex.htm>.

Nebraska Department of Health and Human Services. 2008. “Hastings Regional Center.” Available at <http://www.hhs.state.ne.us/beh/rc/hrcserv.htm>.

Nebraska Department of Health and Human Services. 2010. “Lincoln Regional Center.” Available at <http://www.hhs.state.ne.us/beh/rc/lrcserv.htm>

Painter, George. 1991. “Nebraska.” The Sensibilities of Our Fathers: The History of Sodomy Laws in the United States. Available at

<http://www.glapn.org/sodomylaws/sensibilities/nebraska.htm>.

Paul, Julius. 1965. “‘Three Generations of Imbeciles Are Enough’: State Eugenic Sterilization Laws in American Thought and Practice.” Unpublished manuscript. Washington, D.C.: Walter Reed Army Institute of Research. Available at

Reilly, Philip R. 1991. The Surgical Solution: A History of Involuntary Sterilization in the United States. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

“Review of Nebraska Survey of Social Resources by Phyllis Osborne, director.” June 1938. The Social Service Review. 12, 2: 361-362.

Rietsch, Pam. 2002. “Semi-Centennial History of Nebraska, 1904.” NEGenWeb. Available at <http://www.usgennet.org/usa/ne/topic/resources/OLLibrary/SCHofNE/pages/contents.htm>.

Schalock, Robert L. 2002. Out of Darkness and Into Light: Nebraska’s Experience with Mental Retardation. Washington D.C.: American Association on Mental Retardation.

Schmeckpeper, Sheryl. 2000. Norfolk, Nebraska. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing. 38-39, 29.

Shumway, Howard Paine. 1915. Backward and Feeble Minded Children in the Lincoln Public Schools. Lincoln, NE: (Unpublished Thesis).

Thomas, Elmer A. 1962. From Insanity to Sanity: The Development of a Mental Hospital 1889 to 1962 Ingelside, Nebraska. (No publishing information available).

Vose, Clement E. 1972. Constitutional Change: Amendment Politics and Supreme Court Litigation Since 1900. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books.