Massachusetts

Number of Victims

There were no legal sterilizations in this state. While rumors existed of twenty-six young men having been castrated for “curative” purposes around the turn of the twentieth century, there is record of such sterilizations (Paul, p. 585). There is a record of one mentally ill inmate of the Boston State Hospital who was promised release if he consented to sterilization first, and of the sterilization having taken place in 1911 (Paul, p. 586, n. 3)

Precipitating Factors

During the colonial

period, Massachusetts and Connecticut started to segregate the healthy native

population from others by authorizing laws that would quarantine foreign

ships, suppress disreputable medical practitioners or "quacks," and regulate immunizations (Caron, p. 36).

Foreign women in

Massachusetts in the early 20th

century were having on average 50%

more children than native-born women (Caron, p. 45). This large

difference in birth rates was regarded to be a sign that the native

population would be replaced with those of Slavic, Balkan, and

Mediterranean descent. In New England at large it was observed that the

immigrants were having nearly 10 times the

number of children as native residents (Caron, p. 45).

Since

1905,

Massachusetts did have a compulsory vaccination law and those who did

not comply and receive vaccinations were penalized with a five dollar

fine. In Jacobson v. Massachusetts,

the Supreme Court declared that upheld

police power in regard compulsory vaccination (Lombardo, pp. 86, 152).

Vaccinations were deemed

more dangerous than vasectomies, so it was thought that the same

principle,

medical intervention by the state for the benefit of the public good,

could be applied to compulsory sterilization (Lombardo, p. 157).

Massachusetts

was also

fond of Fitter Family contests, which gained prominence in the 1920s

(Rosen p.

113). One of the contests was the delivery of a sermon on

eugenics, with the

reward for the best being $500 (Ordover, p. 33). Fitter Family contests

were efficient ways

to educate the public on the eugenics movement and to make families

acknoqledge their racial and social responsibility (Rosen, p. 113).

The

Catholic Church also

played a role. Lorraine Leeson Campell, president of Planned Parenthood

Federation of America, along with many women voters in Massachusetts

attempted to overturn

the ban on contraceptives in 1940s but were unsuccessful due to

resistance by the Catholic Church (Caron,

p.141). By the end of the second World War, Massachusetts and

Connecticut were the only two

states in the US where doctors could not prescribe contraceptives to

their patients (Caron, p.

117). Moreover, Massachusetts law also prohibited clinics where

patients could receive

birth control and contraceptive surgery, though the neighboring state

of Rhode Island did allow such clinics

(Caron, p. 124). Even though Rhode Island, like Massachusetts, had a

large Catholic population, these clinics survived in the state. Since

it was not available in Massachusetts, many residents went

to Rhode Island to get the contraceptive services they desired (Caron,

p. 145).

Eventually, with the verdict of the Griswold

Supreme Court case, clinics were allowed to open in Massachusetts (Caron, p. 178).

In Robbie Mae Hathaway v.

Worcester City Hospital,

a court case from 1971, a mother asked to receive contraceptive

sterilization from the Worcester City Hospital, as means of permanent

birth control after having eight children (Dowbiggin, Keeping America Sane, pp. 157-158). However, at this point the Massachusetts

hospital had a ban on surgical sterilizations, and denied the woman

surgery. The court found the hospital had violated the equal protection clause of

the 14th Amendment and granted her the surgery (Dowbiggin, The Sterilization Movement, pp.

157-158). Along with Roe v. Wade, the issue of voluntary sterilizations in

America was resolved.

Marriage Laws

At

this time, Western

states had started to institute marriage restriction laws, including

those that would prohibit intermarriage between Asian immigrants and

native-born whites (Caron, p. 53). Eventually these

prohibitions expanded so that the disabled, "imbeciles", and epileptics

were

included. Connecticut was the first state in New England to establish

marriage

restriction laws, and other states soon followed. By 1940,

Massachusetts

had marriage restrictions that applied to "idiots" and "feeble-minded"

persons. People who

had been committed to an institution for mental defectives, the

feeble-minded, or were wards of the state were not allowed to be

married, even if they had been

sterilized in order to be released from the institution (Schuler, pp.

304-305). An insane person committed to a hospital for mentally

defective people or an insane ward of the

state was also not allowed to get married (Schuler, p. 313).

Major Proponents

Eugenicist Harry Laughlin stated that the superintendent of Monson State Hospital, Dr. Everett Flood, was an early advocate and “tester” of eugenic sterilization (cited in Paul, p. 585).

Dr. Storer, the leader of

the anti-abortion campaign, was another major proponent. His reasoning behind

banning abortion was that foreigners, who were “abnormal," were not having

abortions, but the native and wealthy middle-class was (Caron, p. 22). The large

increase in population, and henceforth the increase in subpar individuals, was

wholly due to the large increase in the foreign population.

Though

in general the Catholic

Church in Massachusetts was against sterilization, not all Catholics or

other denominations were against eugenic ideals. Reverend C. Thurston

belonged to the Central Congregation Church. He was a supporter of the

eugenics movement and was

able to convince not only his clergy, but also many Methodists,

Baptists, and Episcopalians, to refuse

to wed couples who did not provide evidence

of both of their physical and mental ability (Rosen, p. 59).

Reverend MacArthur also

contributed to eugenic ideas in Massachusetts by breeding cattle to learn more

about inheritance of traits (Rosen, p. 171). He

was the secretary of the Federation of Churches

in Massachusetts and constantly emphasized how well-suited eugenics was

to

Christian ideology (Rosen, p. 171). Even though preaching was his first

priotiy, he became secretary of the state eugenics committee and later

secretary of the American Eugenic Society committee (Rosen, p. 171).

His role

in the American Eugenic Society was working with clergymen to find ways

to

incorporate eugenics into religion, such as having sermons that related

to

eugenics. He himself did that, and wrote a monthly column relating the

two

(Rosen, p.171).

“Feeder Institutions” and institutions where sterilizations were performed

Massachusetts was among the first of the states to have institutions and hospitals for the sole reason of providing care and treatment to the feeble-minded and other stigmatized groups (Reilly, p. 12). Massachusetts began establishing these institutions in 1848 (Reilly, p. 12).

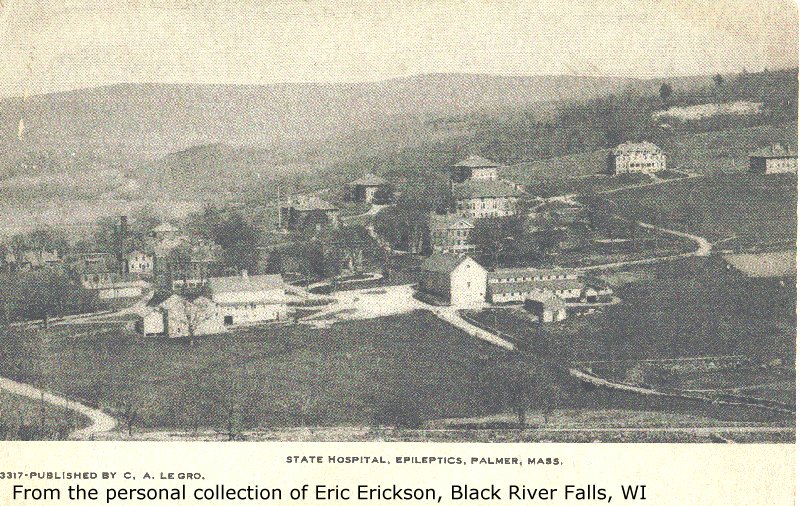

(Photo origin: Rootsweb.com; available at http://www.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~asylums/monson/shericmonson6.jpg)

(Photo origin: Rootsweb.com; available at http://www.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~asylums/monson/shericmonson6.jpg)

The rumors concerning castrations pertain to the Monson State Hospital for Epileptics in Palmer, Massaschusetts, directed by Dr. Flood.

Other Hospitals and Institutions

While no sterilizations

occurred in any of these hospitals and institutions, they are important to

recognize for the segregation of the "unfit."

Fernald State School was named

as such after the first director, who was nationally recognized as an

authority on feeblemindedness (Dowbiggin, Keeping America Sane, p. 101). He believed that IQ

tests were accurate and that those who were feeble were also promiscuous (Dowbiggin, Keeping America Sane, p 101). He ran the school from 1889 to 1924. At one point there were

approximately 1,400 residents, with 1,100 of them having an IQ under 30 (Reilly,

p. 159). There is suspicion that coercive sterilizations occurred here, but those claims are dubious (Reilly,

p. 159). Fernald believed that sterilization

would actually increase illicit intercourse. He thought that sterilization might cure

feebleness, but it would create immorality and insanity (Largent, p. 89).

There

was also the Reformatory

for women in South Farmingham, where there were supposedly thousands of

cases of young repeat-offenders beings sent multiple times. Using these

repeat

offenders, the officials attemped to make a case for criminality due to

inheritance

(Largent, p.120).

From 1829 up until 1930

there were over 25 new hospitals, state reformatory schools, and asylums built

and opened for the care and treatment of various “deficiencies,” including but

not limited to buildings for the blind, idiots, insane, alcoholics, and

epileptics. However, due to a 1969 mandate, most of the state schools have

since been closed (State Hospitals Historical Overview).

Opposition

The

Roman Catholic Church did not support sterilization, whether it was

voluntary or

compulsory, under any circumstances (Robitscher, p. 49). Since in

Massachusetts

the Church had a large presence, this is probably a large factor as to

why no formal compulsory law

was ever established. Catholics tended to agree with eugenic ideas of

protecting the healthy natives from the disease of feeblemindedness,

but disagreed with the

idea of surgery to keep the two groups separate (Rosen, p. 49). The Catholic Church in general also criticized

eugenic leaders, claiming they rushed into applying eugenics without concern

(Rosen, p. 47).

The

African American population also was generally an opposing group. Some claimed that the

only reason Massachusetts lawmakers wanted Planned Parenthood and other clinics was to

wipe out the black race through abortions (Caron, p. 236).

Caron, Simone M. 2008. Who Chooses?: American Reproductive History since 1830. Gainesville: University of Florida.

Dowbiggin, Ian. 1997. Keeping America Sane: Psychiatry and Eugenics in the United States and Canada. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Dowbiggin, Ian. 2008. The Sterilization Movement and Global Fertility in the Twentieth Century. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Largent, Mark A. 2008. Breeding Contempt. Piscataway, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Lombardo, Paul. 2008. Three Generations No Imbeciles. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Ordover, Nancy. 2003. American Eugenics: Race, Queer Anatomy, and the Science of Nationalism. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Paul, Julius. 1965. "'Three Generations of Imbeciles Are Enough': State Eugenic Sterilization Laws in American Thought and Practice." Unpublished Manuscript. Washington, D.C.: Walter Reed Army Institute of Research.

Reilly, Philip R. 1991. The Surgical Solution. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Robitscher, Jonas. 1973. Eugenic Sterilization. Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas.

Rosen, Christine. 2004. Preaching Eugenics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Schuler, Ruth V. 1940. “Some Aspects of Eugenic Marriage Legislation in the United States.” The Social Service Review 14 (2): 301-316.

State Hospitals Historical Overview. Available at <http://www.1856.org/historicalOverview.html>.