Illinois

Number of victims

The only known victim of sterilization was a prisoner who in 1916 was given the choice of going to prison for the crime that he was convicted of or being sterilized. Eugenicist Harry Laughlin simply put it this way: “The prisoner was a pervert and a degenerate, and he decided to get sterilized” (quoted in Paul, p. 577). The judge offered the 65 year old man the opeartion, and reported the sentencing decision, in order to spark public reaction and dialogue about eugenic sterilization in Illinois, which was effective, but did not result in a sterilization law (Laughlin, pp. 354-355). According to Julius Paul (p. 577), this is the only reported sterilization case in Illinois.

Period during which sterilizations occurred

There

were no sterilizations except for the above case in 1916.

Temporal pattern of sterilizations and rate of sterilization

Illinois

neither authorized nor legalized eugenic sterilizations (Paul, p. 577).

Passage of law(s)

No sterilization laws were passed in Illinois. However, in December 1915 a bill for the Commitment and Care for the Feeble-minded Persons was drafted, subsequent to which Illinois House Bill 655 was passed, which allowed courts to permanently institutionalize anyone whom a respectable expert deemed feebleminded. House Bill 654 granted state officials the power to create institutions for such persons. Initially, the bills received considerable support.

Groups identified in the law

House

Bill 654 (eugenic commitment) pertained to the “feebleminded” (Rembis 2003,

p. 91) who were a danger to the community and unable to either

manage "himself and his affairs or of being taught to do so"

(Curtis, p. 156).

Process of the Law

According

to Bill 655, anyone that experts considered to be “feebleminded” could

be

permanently institutionalized. A petition would be

made, claiming the person was feebleminded and a danger to the

community. Then the petitioned person was granted a court hearing

in which two physicians (or a physician and psychologist)

would report the results of their examination of the person to

the court, which would decide whether the person was in need of

supervision (Curtis, p. 156). The law provided for the discharge

of patients if their condition changed, but the process was

difficult, reflecting views that feeblemindedness was a permanent

condition (Curtis, p. 157).

Precipitating factors and processes

Both

male and female reformers in Illinois were willing to experiment with

various

modern state- sponsored social measures, which led to the adoption of

the

eugenic commitment law. Reformers

viewed

the law as way to use science to better society (Rembis 2003, p. 14) and

drew

support from middle class white women who took it upon themselves to do

what

they thought was best as “universal mothers” (Rembis 2003, p. 40). To them

and

many men, eugenics seemed like a simple solution to a more complex

social

problem (Rembis 2003, p. 73). To

eugenic reformers,

institutions seemed to make the most sense because they thought these

institutions would provide care for people who could not care for

themselves and

therefore improve society as a whole (Rembis 2003, p. 39).

Groups targeted and victimized

The

law targeted young women whose delinquent acts were viewed as sexual

transgressions (Rembis 2003, p. 91). For example, fourteen-year-old Elsie

Strubble

was sent to the Cook County Juvenile Court from the Chicago Detention

Home

because she had been raped by one man and three boys and consequently

termed

“incorrigible.” A judge stated that Strubble was a “high-grade

feeble-minded

girl” and in 1924 recommended that she be sent to the Chicago Home for

Girls

(Rembis 2003, p. 90).

Major Proponents

Alfred

E. Walker was a reformer who supported the eugenic commitment law. She

thought

the law would help improve the lives of the state’s unfortunate

individuals. Walker

was chairman of the Legislative Committee of the IFWC (the Illinois

Federation

of Women’s Clubs). Walker was also a member of the committee that

helped create

the original eugenic commitment bill.

In

May 1915, Walker proposed that the IFWC unite on a single way to

provide care

for Illinois’ feebleminded (Rembis 2003, p. 42).

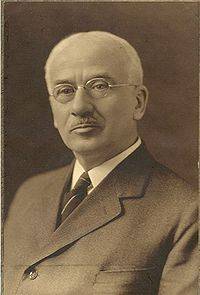

(Photo origin: Wikipedia.com; available at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edward_C._Hayes)

(Photo origin: Wikipedia.com; available at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edward_C._Hayes)

As

Historian Michael Rembis has pointed out, Edward C. Hayes, a founder

and

president of the American Sociological Association, and then a

professor at the Univeristy of

Illinois, urged people to continue to support the use of eugenics to

eliminate

many of the state’s social ills including feeblemindedness (Rembis 2003,

p. 10). In his textbook Introduction to

the Study of Sociology (1916), Hayes wrote that “though

natural selection

no longer gives us a highly selective death rate, eugenics may do

something

toward giving us a selective birth rate (p. 576). He

also used the term “breeding up the human

herd” in approving of the state’s plans (quoted in Rembis 2003, p.

10). He believed feeblemindedness was a result of

both heredity and environment, but he also believed eugenics was the

solution to both (Rembis 2003, p. 54).

Bibliography

Curtis, Patrick A. 1985. "Eugenic Reformers, Cultural Perceptions of Dependent Populations, and the Care of the Feebleminded in Illinois, 1909-1920." Ph.D. Dissertation, Dept. of Social Work, University of Illinois at Chicago, 1983.

Hayes,

Edward Carey. 1916. Introduction

to the Study of Sociology.

New York: D. Appleton and Company.

Paul, Julius. 1965. "'Three Generations of Imbeciles Are Enough': State Eugenic Sterilization Laws in American Thought and Practice." Unpublished ms. Washington, D.C.: Walter Reed Army Institute of Research.

Rembis,

Michael A. 2002. “Breeding up the Human Herd: Gender, Power, and

the Creation of the Country's First Eugenic

Commitment Law.”

Journal

of Illinois History 5,

4: 283-308.