Home

Kaufbeuren-Irsee (Kreis-, Heil- und Pflegeanstalt für Geisteskranke

Kaufbeuren-Irsee)

The Kinderfachabteilung in Kaufbeuren was established in December 1941 (as

the second of three in Bavaria) and was in operation until mid-April

1945 (and children were killed until June 1945). The clinic's medical

director was Dr. Valentin Faltlhauser, who was directly responsible for this

ward. The ward (an extension) in Irsee, which is close by, opened a few

months later. Its medical director was Dr. Lothar Gärtner,

the clinic's deputy director, who was directly responsible for the ward in

Irsee and committed suicide in 1945. Dr. Faltlhauser received

a sentence of 3 years for instigation to be an accessory to manslaughter and

was pardoned by the Bavarian secretary of justice in 1954. He died in 1961.

Source: U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum

(http://www.ushmm.org/wlc/media_ph.php?lang=en&ModuleId=10005200&MediaId=3316)

Source: U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum

(http://www.ushmm.org/wlc/media_ph.php?lang=en&ModuleId=10005200&MediaId=3316)

221 children died in the special children's ward in Kaufbeuren and Irsee.

Dr. Faltlhauser collaborated with another doctor in conducting

tuberculosis experiments on children in the Kinderfachabteilung, of whom the

majority died as a consequence.

Heuvelmann (2014: 58) notes that 400 person were deported from the Irsee

facility as part of the "T4" program, and 600 died during the war

thereafter. The first children were admitted in November 1940, and between

the end of 1945 to the end of 1945 108 minors died there.

Recent research (Steger 2006) has shown the role of the three Bavarian

"special children's wards" (Ansbach, Eglfing-Haar, and Kaufbeuren) as

suppliers of tissue specimens for the Neuropathological Research Institute

in Munich. With certainty Eglfing-Haar provided 144, and probably as many as

297, slide preparations of brain material from the “Special Pediatric Unit”

in Eglfing-Haar, whereas 23 came from Kaufbeuren and 25 from Ansbach.

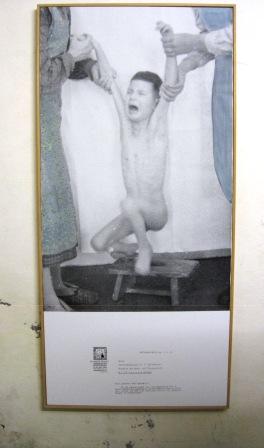

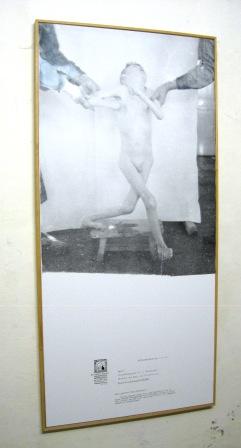

Even though American troops entered Kaufbeuren in late 1945, the clinic site

was initially left undisturbed because of a putative occurrence of typhus

there. After military personnel entered the clinic, it was discovered that a

4-year old, Richard Jenne, had become the last victim of "children's

euthanasia" on May 29, 1945 (see for his picture provided by the

US Holocaust Memorial Museum here; and for the document that is part of the

extensive Nuremberg trial record available online here).

Kaufbeuren was probably known of having been one of the most notorious sites

of medicalized murder in Bavaria, as indicated in the Munich newspaper of 7

July 1945, which titled its story, printed on its cover, on Kaufbeuren "Mass

murder in the asylum" (Klee p. 452).

Kaufbeuren

In Kaufbeuren a recognition of the past murders did not begin until the

early 1980s. As late as 1976, when the Bezirk Schwaben published a volume on

the 100 year anniversary of the psychiatric clinic Kaufbeuren one of the

directors after WWII noted in an assessment of the era 1933-1945 that a

special children's ward existed after Dec. 1941 but did not mention the

murder of children. Dr. Faltlhauser was judged in the following way: "Seine

Arbeit war im Grund getragen von Liebe und Sorge um die Kranken" (Bezirk

Schwaben, p. 55; "His work was basically motivated by his love and care for

the sick") and "Die Entwicklung des Hauses verdankt ihm viel" (Bezirk

Schwaben, p. 55; "The progress of the clinic owes a lot to him"). Just two

years earlier, in 1974, the Catholic clergyman of the clinic had put up

a sign in the clinic chapel referring to the victims of "Euthanasia,"

but the sign disappeared quickly, likely by order of the clinic director.

Changes began to occur when in the wake of psychiatric reform in the 1970s

the new director Dr. Michael von Cranach and others confronted the

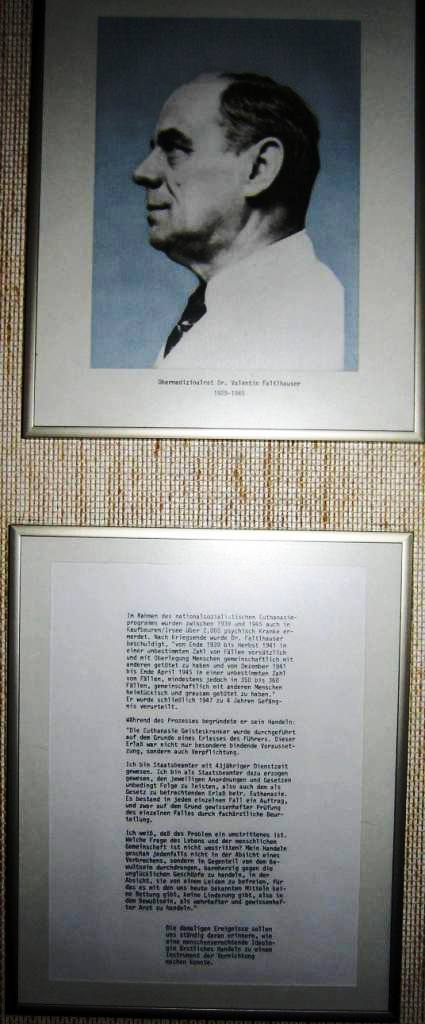

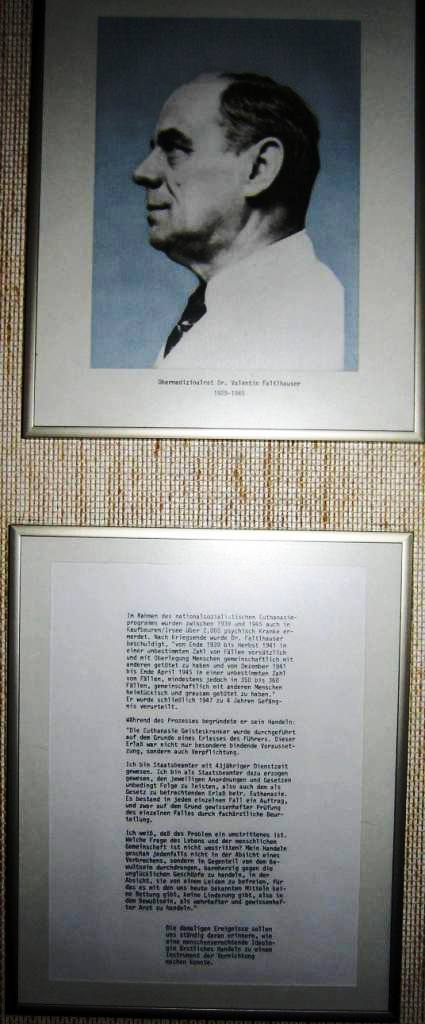

institution's Nazi past. In. the hallway of the administrative part of the

clinic Dr. Michael v. Cranach and a group of other physicians instigated the

placement of a text beneath a picture of Dr. Faltlhauser that details

his involvement in "euthanasia." The text ends with the note that "the

events in the [Nazi] past must always remind us how an ideology contemptuous

of human life can turn the actions of a physician into an instrument of

extermination."

Source: Author.

Source: Author.

A boulder that has the inscription "In memory of the 2000 patients of the

hospital Kaufbeuren-Irsee who were murdered between 1940 and 1945 as victims

of [Hitler's] 'Euthanasia decree'" together with murdered patients' names

was placed on site. The massive stone is meant to signify the historical

burden of the "Euthanasia" crimes that rests on the clinic. Patients,

visitors, relatives of victims, and staff members leave little mementos such

as candles there.

Source: Author.

Source: Author.

Source: Erwin Resch

The boulder is located at a place on clinic property that is frequented

by the public because it is located close to a spot that offers some of the

best views of the town Kaufbeuren. The memorial was conceived, financed, and

implemented by a group of physicians, psychologists, and nurses on the

occasion of the 50th anniversary in October 1989 of the beginning of the

"Euthanasia" program. Dr. v. Cranach headed a group of personnel,

particularly resident physicians, who sought to place a memorial on clinic

grounds. An annual commemoration takes place on January 27 in which

local community members, clinic staff, clergy as well as nursing

students participate. "Euthanasia" is a part of the nursing students'

curriculum, and it is also a topic that is addressed in advanced

professional training (berufliche Weiterbildung) there.

Dr. Michael v. Cranach, who has hosted and been part of commemorative

events since the early 1980s, has also conceived the exhibit "In memoriam"

(see in exhibits), which has as one of its foci the life and death of Ernst

Lossa, who was murdered at Kaufbeuren.

Source: Author.

Source: Author.

On site (at the former clinic cemetery) is also another memorial of the

Irsee artist Peter Müller since summer 2006. It is close to an older

memorial and has the inscription 'In commemoration of the dead and victims

of the NS-Euthanasia.' It is coated with a reddish patina may remind the

visitor of the impermanence of all that is material and ideological. The

stark cubic shape of the memorial itself is open to interpretation: does it

stand for the harsh ideology of National Socialism putting a stop to any

humane approach to illness and any resistance? Or is its shape intended to

remind the visitor of the shape of the chimney of the crematorium that was

erected in 1944 on site to burn the victims? - Given its rather remote

location, the memorial presently does not seem to engender active

commemoration.

Irsee

In Irsee the historical chronicle of the cloister published in 1981

made no mention of the involvement of the institution in the Nazi euthanasia

project. However, in that year a bronze sculpture by Martin Wank was

erected on the grounds of the former clinic cemetery (where the victims

were believed to have been buried, although more recent research shows the

burial grounds to have been farther from the cloister). It was the first to

commemorate the "euthanasia" victims at a site of a former

Kinderfachabteilung in West Germany, and the second overall (after

Kocborowo). It was commissioned by the district Schwaben in the context of

the renovation of the Kloster Irsee and its re-dedication as a conference

and education center. A small panel on the display reads "let me sing your

passion" (a reference to the title of a ecclesiastical hymn, by Johann

Michael Denis). As reported by the institution's priest, patients sang

this song when they knew that they marked for death and were to die (Römer,

p. 143). A plate is attached, with the text "In commemoration of the silent

victims of political dictatorship." The memorial employs a somewhat effusive

symbolism, explained in the booklet 'Memento for the euthanasia victims

of Irsee': the lowest level of the memorial depicts a quagmire of guilt (and

perhaps desperation, depicted by extending limbs) that holds on firm to the

tree of death bearing the world as its fruit. On top of it is the Redeemer,

who turns the world in his resurrection into the cradle of good.

Source: Author.

Source: Author.

A display at the memorial addresses the historical

events as well; its text is stated in the history section of the

cloister's webpage (see the following). Before the plaque was installed, a

sign directing visitors to the memorial had copies of the "Memento"

attached to it.

Source: Author.

Source: Author.

The history part of the website of

the Kloster Irsee (where Irsee's part of the special children's

ward was housed), now called the "Swabian Conference and Educational Center

Cloister Irsee" is explicit about its past: "1939-1945: The inhuman racial

ideology of the National Socialists and the resulting activities for the

'extermination of worthless life' also affect Irsee: More than 2000 patients

[adults and children] from Kaufbeuren/Irsee are deported to extermination

facilities, die upon the provision of a fat free starvation diet [E-diet] or

are directly killed as a result of injections and overdoses of medications."

Parts of this text are also mentioned in the overview of the clinic's

history in the hallways of the cloister.

Most recently, the former pathology (Prosektur) of the Irrenanstalt has been

reopened as a memorial. A plaque at the entrance of the building reads:

"Cloister Irsee. Memorial. By having a memorial on the former cemetery

grounds, a memorial room in the facility of the then pathology, and [three]

stumbling blocks at the front of the cloister the Swabian Educational Center

Irsee commemorates the murder of the patients by Nazi "euthanasia" in the

facility Kaufbeuren/Irsee. Let the fate of the victims be a warning to us:

The dignity and the life of the sick, the marginalized in society, and those

who need assistance deserve particular protection!"

Source: Author.

Source: Author.

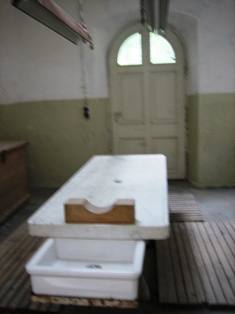

The memorial contains the dissection table that has been in place since the

end of WWI (a copy of it was made for the exhibit on euthanasia in the

Imperial War Museum). The anteroom contains an art installation by Beate

Passow (1996), a triptych originally entitled "...most courteously I wish to

ask thay you answer the following questions..." (a request made by Dr.

Hensel, carrying out deadly tuberculosis experiments on children of the

Kinderfachabteilung) with three pictures, each depicting a child, which are

also included in Dr. v. Cranach's exhibit "In Memoriam" (see exhibits).

Source: Author.

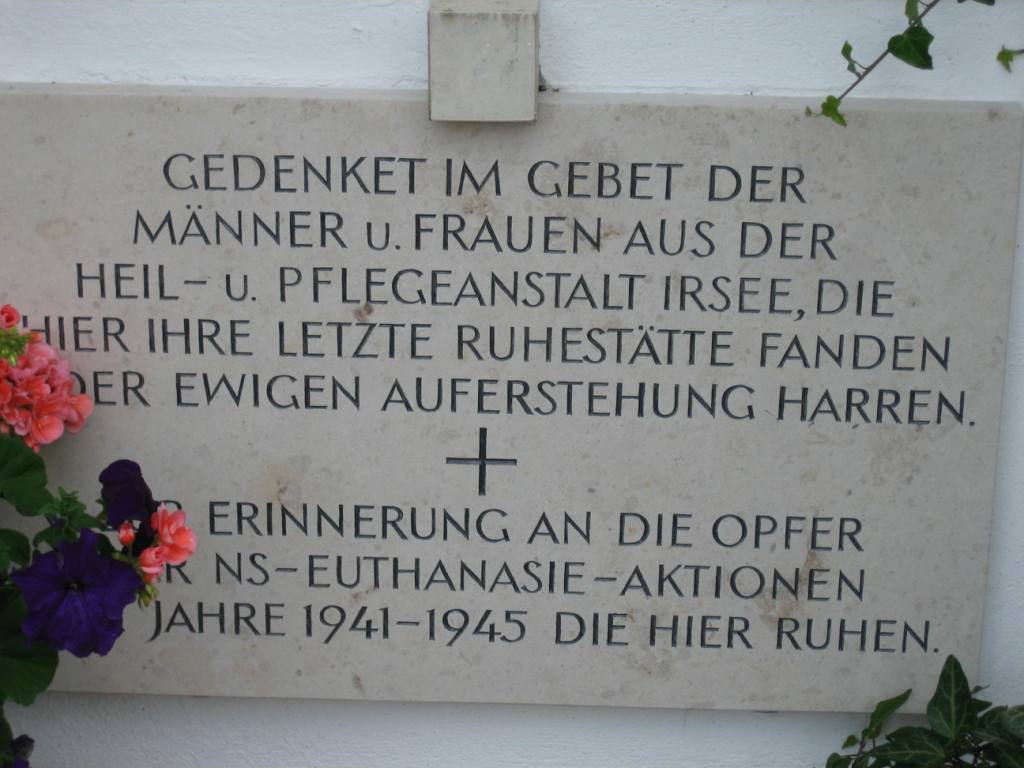

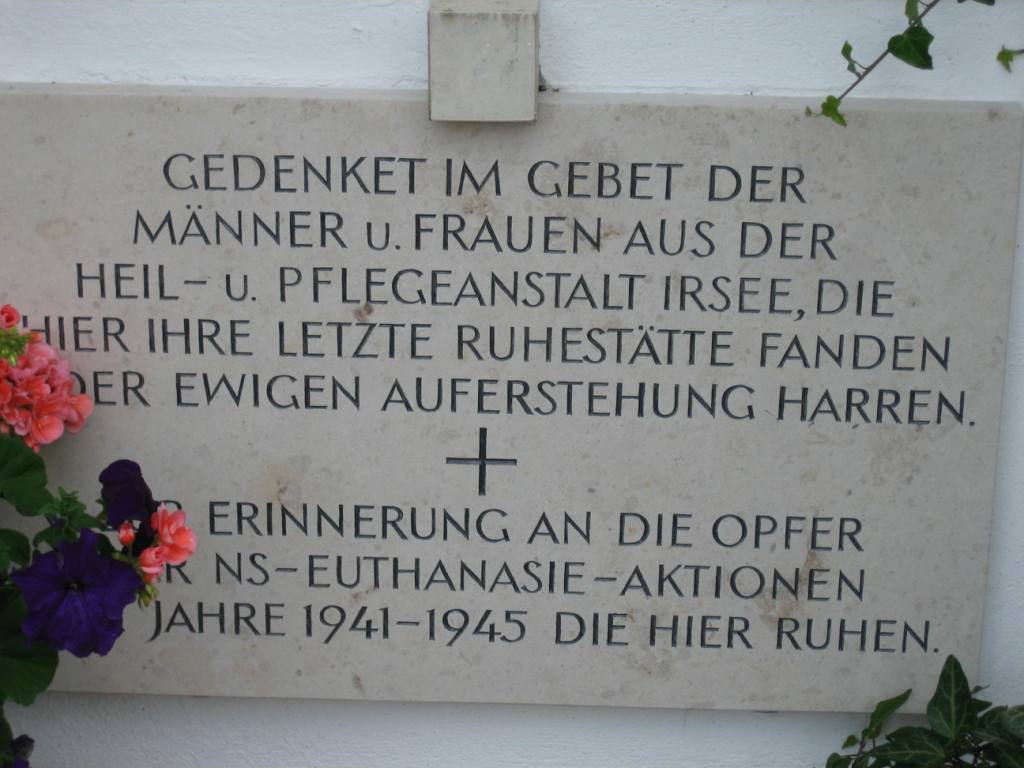

At the cemetery there is a plaque in a small chapel. It was restored in 2006

and to the existing text, which read "Commemorate in prayer the men and

women of the clinic Irsee, who found their final resting place here and

await eternal resurrection," the following text was added: "In memory of the

victims of the NS-Euthanasia-Actions of 1941-45 who rest here."

Source: Author.

Source: Author.

Source: Author.

Source: Author.

There is a stela by the sculptor Alfred Neumann close to the former

pestilence cemetery (Seuchenfriedhof) of the clinic established in 2005,

which has the following inscription: 'In commemoration of 47 dead persons of

the NS-Euthanasia actions who fell victim to a typhus epidemic in spring

1944.' It was erected at the end of 2005 based on a resolution of the city

council. Its 47 small squares relate to the number of the victims.

Source:

Author.

Source:

Author.

Source:

http://www.kloster-irsee.de/deutsch/kloster_irsee/pressearchiv1.php?p=537

Source:

http://www.kloster-irsee.de/deutsch/kloster_irsee/pressearchiv1.php?p=537

In 2009, stumbling blocks (Stolpersteine) for three victims of "euthanasia"

were placed at the cloister Irsee.

Source: C. Kaelber.

Source: C. Kaelber.

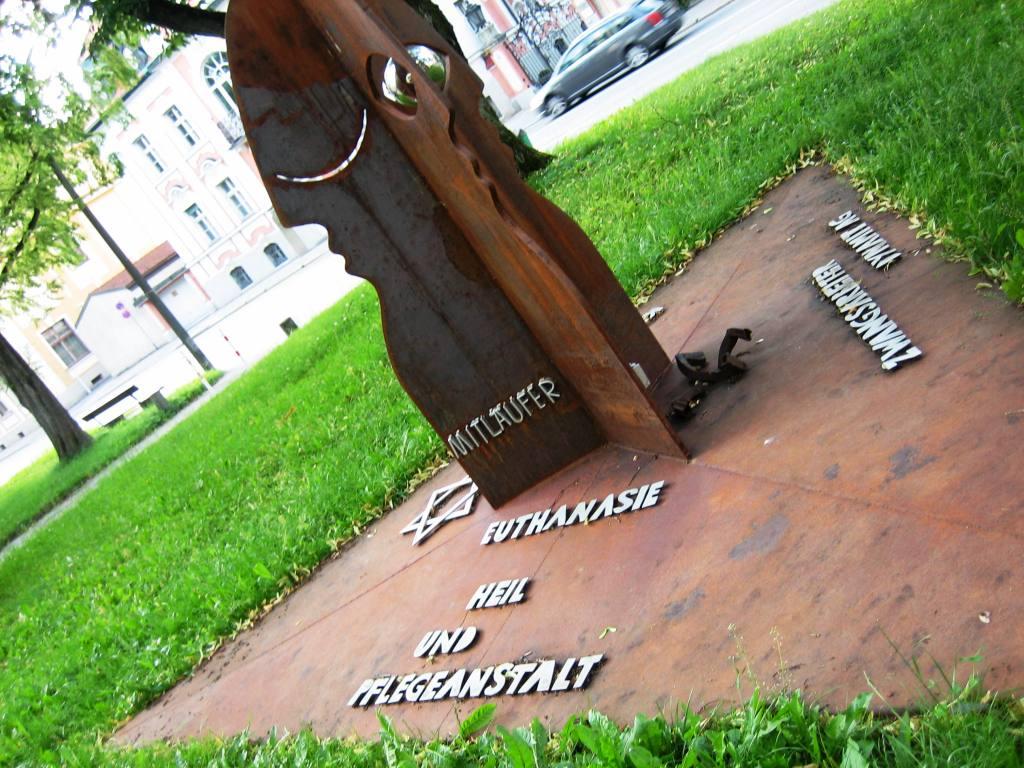

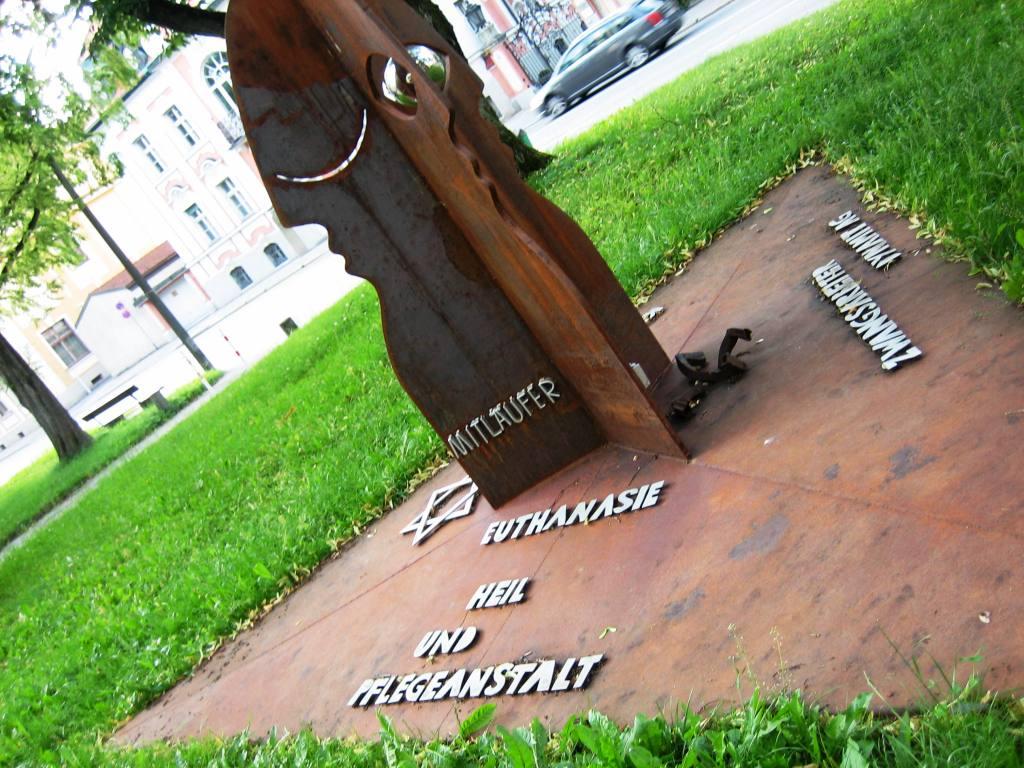

In addition, a youth group, "Die Salzstreuer' (Saltshakers), have advocated

for the erection of a centrally located memorial for victims of National

Socialism in Kaufbeuren. "Euthanasia" as a word is inscribed in the

memorial, which was created by the artist Peter Müller and dedicated on 9

November 2008, the 70th anniversary of the Kristallnacht.

A text display explains the context.

Source: C. Kaelber

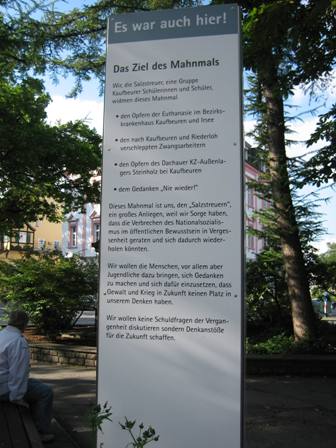

The group also has put together an exhibit, "Es war auch hier: Kaufbeurer

Schicksale im Dritten Reich" (It happened here too: The Fate of Kaufbeuren

Residents in the Third Reich), which includes a section on children's

"euthanasia (here). The group has a website with further information.

Source: Allgäuer Zeitung (3 November 2010, p. 24)

On 1 November 2010, the author Robert Domes organized a display of 500

candles at the former cemetery at Irsee on All Saints' Day (see also: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Yitu5mTd49k). This

events has since been repeated.

A film about Ernst Lossa, one of the victims, has been reported to be

planned. The student Sina Moshehi received the Bertini prize for his

documentary "Zum Andenken: Vom Leben und Sterben des Ernst Lossa" (In

memory: Life and Death of Ernst Lossa) (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dhuHbm9mvZw).

The reopened city museum of Kaufbeuren addresses "euthanasia" via

electronic media in its facility.

A section entitled "A situation at the Freiburg public youth office"

(Heidtke/Rössler 1995, pp. 335-39) describes the (rather remarkable) refusal

of four young students of the Catholic Social Women's Office (Soziale

Frauenschule) in Freiburg who interned at the public youth office to ready

disabled children for transport to the special children's ward Kaufbeuren

and accompany them in 1944 because it was an open secret that Kaufbeuren was

an "extermination center."

In 2014, a stumbling block was placed in Ludwigsburg in memory of the

victim Anita Henk, and a web

page as well as a youtube

video provides information about her fate.

The victim Rolf Mühlhahn is commemorated here.

Digital reproductions of records of the Grafeneck trial relate to a number

of children from Wurttemberg and Baden who died in the Kaufbeuren facility

between 1941 and 1945 (http://www.landesarchiv-bw.de/plink/?f=6-902860;

).

Literature

Benzenhöfer, Udo. 2003. "Genese und Struktur der

'NS-Kinder- und Jugendlicheneuthanasie.'" Monatsschrift

für Kinderheilkunde 151: 1012-1019.

Bezirk Schwaben. 1976. Hundert Jahre

Nervenkrankenhaus Kaufbeuren. Kaufbeuren: n.p.

Cranach, Michael von. 1987. "Die Psychiatrie in der Zeit des

Nationalsozialismus." In Verband der Bayerischen Bezirke, 150

Jahre Psychiatrie in Bayern (broschure).

———. 2008. "Geschichte des Nervenkrankenhauses Irsee." Lecture at

the conference "60 Jahre Allgemeine Erklärung der Menschenrechte: Das Recht

auf Gesundheit in Deutschland," Irsee. Available on youtube (here).

Domes, Robert. 2008. Nebel

im August: Die Lebensgeschichte des Ernst Lossa. Munich: cbt.

Frei, Hans, ed. 1981. Das Reichsstift

Irsee: Vom Benediktinerkloster zum Bildungszentrum. Weissenhorn:

Anton H. Konrad Verlag.

Heidtke, Birgit, and Christina Rössler. 1995. Margarethas

Töchter: Stadtgeschichte der Frauen von 1800 bis 1950 am Beispiel

Freiburgs. Freiburg: Kore.

Heuvelmann, Magdalene. 2013. "Wer in

einer Gottesferne lebt, ist im Stande, jeden Kranken wegzuräumen":

"Geistliche Quellen" zu den NS-Krankenmorden in der Heil- und

Pflegeanstalt Irsee. Irsee: Grizeto.

--------. 2014. "'Wer in einer Gottesferne lebt, ist im Stande,

jeden Kranken wegzuräumen': Geistliche Quellen zu den NS-Krankenmorden in

der Heil- und Pflegeanstalt Irsee." Pp. 52-70 in Die

"Euthanasie"-Opfer zwischen Stigmatisierung und Anerkennung: Forschungs-

und Ausstellungsprojekte zu den Verbrechen an psychisch Kranken und die

Frage der Namensnennung der Münchner "Euthanasie"-Opfer, edited

by Gerrit Hohendorf, Stefan Raueiser, Michael von Cranach, and Sibylle von

Tiedemann. Munster: Kontur.

Klee, Ernst. 1995. "Euthanasie" im

NS-Staat. Frankfurt: Fischer.

Mader, Ernst T. 1985 (first ed. 1982). Das

erzwungene

Sterben von Patienten der Heil- und Pflegeanstalt Kaufbeuren-Irsee

zwischen 1940 und 1945 nach Dokumenten und Berichten von Augenzeugen.

Blöcktach: Verlag an der Säge.

Nießeler, Uli. 1984. "Vernichtungszentrum Kaufbeuren-Irsee." Türspalt

(10).

Ost, Suzanne. 2006. "Doctors and Nurses of Death: A Case Study of

Eugenically Motivated Killing under the Nazi `Euthanasia' Programme." Liverpool Law Review 27: 5-30.

Pötzl, Ulrich. 1995. Sozialpsychiatrie,

Erbbiologie und Lebensvernichtung: Valentin Faltlhauser, Direktor der

Heil- und Pflegeanstalt Kaufbeuren-Irrsee in der Zeit des

Nationalsozialismus. Husum: Matthiesen.

Raueiser, Stefan, and Bertram Sellner, eds. 2009. "...man

stolpert mit dem Kopf und mit dem Herzen": Zum Gedenken an die Opfer der

Heil- und Pflegeanstalt Kaufbeuren/Irsee. Irsee: Grizeto Verlag.

Resch, Erich. 2006. "Die Begräbnisstätten der Heil- und Pflegeanstalten bzw.

des Bezirkskrankenhauses Kaufbeuren und Irsee." Kaufbeurer

Geschichtsblätter: Mitteilungsblatt des Heimatvereins Kaufbeuren e.V.

17, 8: 258-78.

Römer, Gernot. 1986. Die grauen Busse in

Schwaben: Wie das Dritte Reich mit Geisteskranken und Schwangeren umging:

Berichte, Dokumente, Zahlen und Bilder. Augsburg: Presse-Druck- und

Verlags-GmbH Augsburg.

Schmidt, Martin, Robert Kuhlmann, and Michael von Cranach. 1999. "Heil- und

Pflegeanstalt Kaufbeuren." Pp. 265-325 in Psychiatrie

im Nationalsozialismus: Die Bayerischen Heil- und Pflegeanstalten zwischen

1933 und 1945, edited by M. von Cranach and H.-L. Siemen. Munich:

R. Oldenbourg Verlag.

Schweizer-Martinschek, Petra. 2004. "Die Versuche an behinderten Kindern in

der Heil- und Pflegeanstalt Kaufbeuren-Irsee 1942-1944." Pp. 231-59 in Nationalsozialismus in Bayerisch-Schwaben:

Herrschaft, Verwaltung, Kultur, edited by Andreas Wirsching.

Ostfildern: Jan Thorbecke.

———. 2008. "NS-Medizinversuche: 'Nicht gerade körperlich besonders wertvolle

Kinder.'" Deutsches Ärzteblatt

105(26): A-1445.

Steger, Florian. 2002. "Medizinische Forschung an Kindern zur Zeit des

Nationalsozialismus: Die 'Kinderfachabteilung' der Heil- und Pflegeanstalt

Kaufbeuren-Irsee." Medizin, Gesellschaft

und Geschichte 22: 61-88.

———. 2004. "'Ich habe alles nur aus absolutem Mitleid getan':

'Kinderfachabteilung' der Heil- und Pflegeanstalt Kaufbeuren-Irsee:

'Kindereuthanasie'." Monatsschrift

Kinderheilkunde 152(9): 1004-10.

———. 2005. "Kinder als Patienten der Heil- und Pflegeanstalt

Kaufbeuren-Irsee: Die 'Kinderfachabteilung' in den Jahren 1941-1945." Sudhoffs Archiv 89(2): 129-50.

———. 2006. "Neuropathological research at the 'Deutsche Forschungsanstalt

für Psychiatrie' (German Institute for Psychiatric Research) in Munich

(Kaiser-Wilhelm-Institute): Scientific utilization of children's organs from

the 'Kinderfachabteilungen' (Children's Special Departments) at Bavarian

State Hospitals." Journal of the History

of the Neurosciences 15: 173-85.

Topp, Sascha. 2004. “Der ‘Reichsausschuss zur

wissenschaftlichen Erfassung erb- und anlagebedingter schwerer Leiden’:

Zur Organisation der Ermordung minderjähriger Kranker im

Nationalsozialismus 1939-1945.” Pp. 17-54 in Kinder in der

NS-Psychiatrie, edited by Thomas Beddies and Kristina Hübener.

Berlin-Brandenburg: Be.bra Wissenschaft.

———. 2005. "Der 'Reichsausschuß zur wissenschaftlichen

Erfassung erb- und anlagebedingter schwerer Leiden': Die Ermordung

minderjähriger Kranker im Nationalsozialismus 1939-1945." Master's Thesis

in History, University of Berlin.

Concerning "Euthanasia" trial(s)

for this location

Bauer, Fritz et al., eds. 1968-1981. Justiz

und NS-Verbrechen: Sammlung deutscher Strafurteile wegen

nationalsozialistischer Tötungsverbrechen, 1945-1966. Amsterdam:

University Press Amsterdam. Vol. 5, pp. 175ff.

Bryant, Michael S. 2005. Confronting the

"Good Death": Nazi Euthanasia on Trial, 1945-1953. Boulder:

University of Colorado Press. Pp. 192-98.

Freudiger, Kerstin. 2002. Die juristische

Aufarbeitung von NS-Verbrechen. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck. Pp. 272-78.

last updated on 13 September 2015

Source: U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum

(http://www.ushmm.org/wlc/media_ph.php?lang=en&ModuleId=10005200&MediaId=3316)

Source: U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum

(http://www.ushmm.org/wlc/media_ph.php?lang=en&ModuleId=10005200&MediaId=3316)

Source: Author.

Source: Author. Source: Author.

Source: Author.

Source: Author.

Source: Author. Source: Author.

Source: Author. Source: Author.

Source: Author. Source: Author.

Source: Author.

Source: Author.

Source: Author. Source: Author.

Source: Author. Source:

Author.

Source:

Author. Source:

http://www.kloster-irsee.de/deutsch/kloster_irsee/pressearchiv1.php?p=537

Source:

http://www.kloster-irsee.de/deutsch/kloster_irsee/pressearchiv1.php?p=537 Source: C. Kaelber.

Source: C. Kaelber.