Gallery 2: Market Workers

in Ukraine

All images

are the property of Jennifer Dickinson

Please do

not copy or use without express permission.

Since the breakup of the Soviet Union in 1991,

the Ukrainian economic system has been undergoing massive, and often disorganized,

restructuring. For most Ukrainians, this has meant changing their workplace,

profession, or even life goals. For the past several years, beginning

with a project in summer 2000, I have been doing research on Ukrainian markets,

called "bazary" (bazaars), focused on markets in the Zakarpattja region

of Ukraine. Although somewhat similar to an American flea market, the

bazar occupies a very different place in the social and economic landscape

of Ukraine. Even now, when more retail stores have opened in Zakarpattja

towns, the bazar is still the place most people go to make purchases

both large and small - everything from mayonnaise and diapers to prom dresses,

wedding rings, and televisions can be, and are, bought at local or regional

bazary.

In the early days of the late- and post- Soviet

period, market work offered a get-rich-quick appeal to young people willing

to dive into the market head first. Bazary gradually left the

streets and took over unused stadiums or courtyards as sellers installed semi-permanent

booths. Although most people did their shopping at bazary, they

still regarded bazar workers as shady, untrustworthy characters. Indeed,

selling goods for profit had been outlawed in the Soviet Union, and even

as Ukrainian society moved towards a market economy, the profit motive remained

culturally stigmatized. By the mid-1990's however, many of the state-run

enterprises in Zakarpattja had closed, leaving a large, highly-educated workforce

in their 30's, 40's and 50's without work. In rural areas, most of

the men became involved in migrant labor to Russia, Central Europe and other

locales, where they primarily do construction or farmwork. Meanwhile,

many women turned to work at the bazar. Gradually, these new workers

began to outnumber the original sellers, and the moral evaluation of market

work started to shift. Although "selling" remains morally ambiguous,

even for many sellers, it is becoming an accepted occupation in a labor market

that offers workers few options for traditional employment in state enterprises

such as factories, schools, and local government bodies.

Below are two sets of photographs: a few

images of different types of markets and stores; and photographs of sellers

from all over Zakarpattja with their goods.

Shoppers have gradually seen an increase in their

options. Western-style supermarkets have now opened in many major

Ukrainian cities, but the bazar still reigns supreme as it did when

I took these photographs in 2000.

Pivdennyj (Southern) Bazar, Lviv, Ukraine, 2000.

Visitors are greeted with a Soviet-style exhortation:

To the Market with Ukrainian Investment Bank!

Here, a much smaller bazar in a Zakarpattja

village. Each type of product is sold in a different area - foodstuffs

are sold along the street under umbrellas, while clothing and household goods

occupy the permanent stalls whose roofs are visible on the lefthand side

of the picture. Behind the stalls, next to the creek, people selling

"humanitarian aid" - used clothing donated from abroad, spread their good

directly on the ground.

In rural areas, villages alternate market days,

and the same group of sellers will travel from market to market, working

six days a week.

Here a villager has set up a "budka" - a small stall

or hut outside her house. She sells basic goods: ice cream, beer,

margarine, oil and macaroni to neighbors who would otherwise have to walk

a mile to the local store.

Another type of store that has become popular in

villages is the in-home shop, such as this small store in the vestibule of

a home. This homeowner has contracted with a bread factory to bring

her fresh bread daily, and neighbors prefer to buy it from her than from

the state store, where the quality is often lower.

Here I am posing with the cashier at a state store

in a Zakarpattja village, which was stocked mostly with alcohol, instant

coffee, candy and cigarettes on my last visit there in 2003.

As I discovered in my interviews with 40 market

workers from all over Zakarpattja, the average market worker is a woman with

some post-secondary education who has worked previously in a professional

occupation such as teaching or nursing.

Clothing seller, Verxnje Vodjane 2000. The

"humanitarian aid" clothing for sale is visible through the back curtain of

her booth.

Seller, Verknje Vodjane, 2000. Sellers jealously

guard their locations, even "subleasing" them to others when they are away

to prevent poaching. When I saw this woman again in 2003, she was selling

in the same spot.

Notions seller, Zolotorevo, 2000. At a tiny

market such as this one, with fewer than 20 stalls, sellers make a special

effort not to overlap in their inventory.

Furniture seller, Solotvino 2000. Solotvino

attracts a multiethnic range of local sellers, such as this Romanian salesman,

as well as sellers who cross the border from Hungary and Romania to sell

food and clothing items.

A woman selling coffee, canning lids and socks sets

up her booth in the Xust marketplace early on a fall morning. The front

of her stall says "Vegetables - fruits" in faded letters, a faint reminder

of the Soviet-era life of this space, when only home-grown vegetables were

sold here.

Meanwhile, the vegetable sellers have been forced

outside the walls of the Xust marketplace, and now sell their wares on the

streets surrounding the market itself.

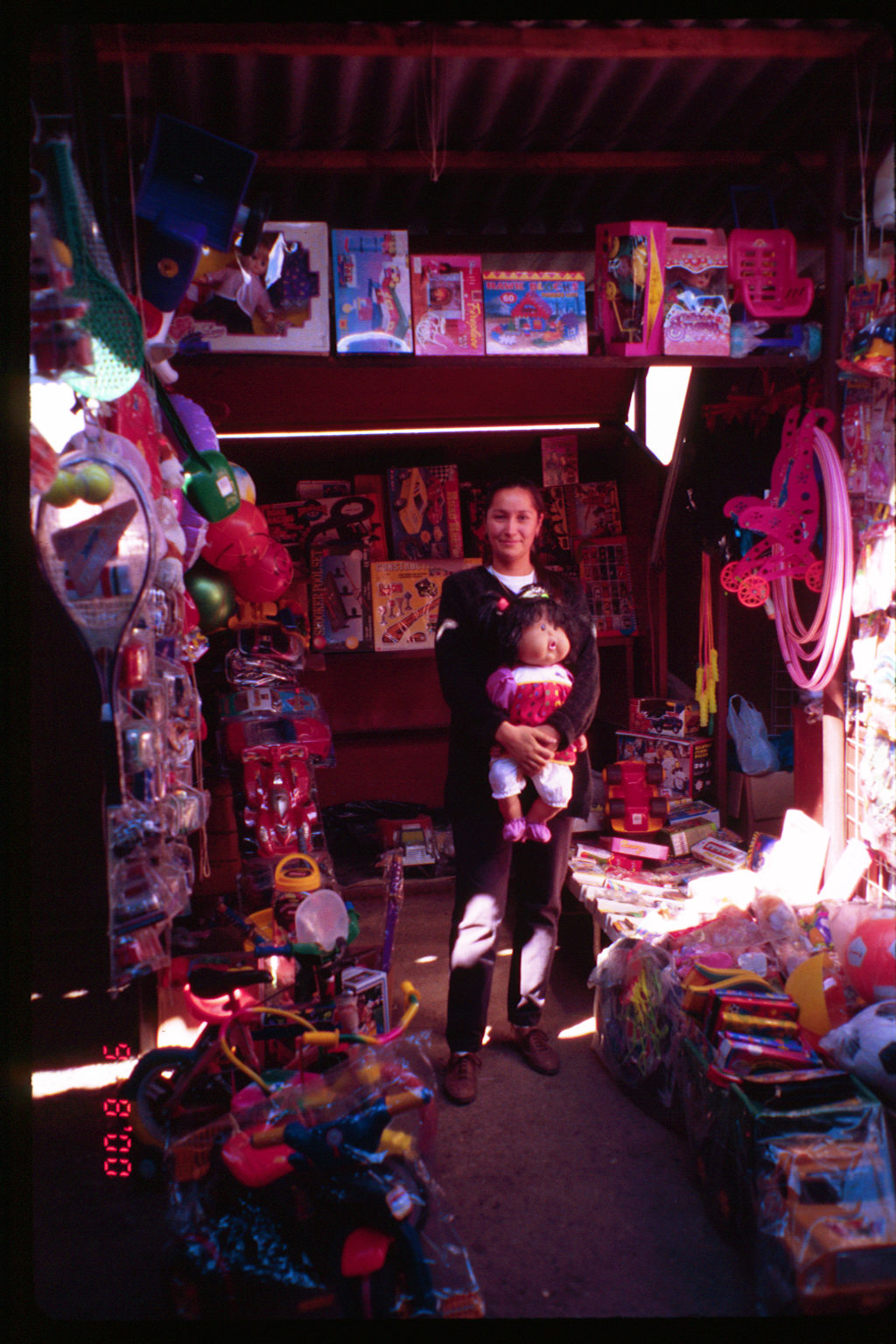

This toyseller at the Uzhhorod market also works

part time as a tailor, the profession she was trained for. At the market,

she works on the lowest rung of the selling hierarchy, as a "seller" who

works on commission.

Sports clothing seller, Uzhhorod 2000. This

woman is a "realizator," meaning that she has a relationship with a wholesaler,

who imports goods and then offers them to her for resale.

These jeans sellers at the Uzhhorod market are a

step up the ladder - they purchase and sell their own merchandise.

A shoe seller in Uzhhorod has cleared her table

to set up a hostyna, a "spread," hosting a small party for her fellow

workers to mark her daughter's wedding. In my interviews with market

workers, I found ample evidence that market workers, especially women, have

developed close relationships with others at the market, recapturing to some

extent the feeling of the "labor collectives" that formed the center of Soviet

work life. The celebration of important events, such as birthdays,

with fellow market workers was cited by many people I interviewed as proof

that they did belong to a collective.

Return

to Photo Gallery Main

Home