Produced by University of Vermont HP 206 Researching Historic Structures and Sites students in Fall 2020 |

Diners as Nourishing Places

By Dominick Agresta

Nourishment is a more intricate concept than many people give it credit for. The first association people might make when thinking of nourishment is with food providing the nutrients that people need, which is why eateries are a good place to start when considering what a nourishing place might be. If we think of the definition of nourishment in an expanded way, making it more inclusive of intangible things, it gives a clearer view of why certain eateries are chosen over others. Every eatery has its own feeling – no matter if you are looking at a nationwide chain or a local joint – that draws customers. The feeling of a place goes beyond just its menu, making it possible for two similar businesses to feel completely different. The goal of this research is to use three diners in Burlington, Vermont as examples of why diners can be considered nourishing places, specifically when looking at their unique atmosphere and design in connection to the extended definition of nourishment.

Every diner shares a common goal, which is also their most distinguishing trait: good food at a low price that gets served quickly. While this might seem like a basic idea that is used by other types of eateries, there isn’t anywhere that does it like a diner can. Restaurants aren’t as efficient and are more formal while fast food doesn’t have the same conversational or welcoming feeling. Diners check all the boxes without making visitors feel like they are being rushed.

Diners have gained a connotation of being a friendly, inexpensive gathering place for people from a variety of occupations and generations. The diversity in customers at a diner opens conversation up to any topic. With college students who spent a long night out, workers that are just starting their day, and prominent politicians looking for an informal view on policy, the stools and booths at a diner have been home to conversations and viewpoints of every kind.

While many diners have a modern style that has drastically changed since they opened, there are a few historic diners that maintain the majority of their original design. There are a few diners in Burlington and South Burlington, Vermont that don’t just show traces of their original design, but have been largely unaltered through decades of business. These diners have not lost their classic charm, which is a key component to the feeling that customers get when they walk inside. Each step through the diner brings you closer to a warm meal and welcoming feeling that not many modern restaurants can emulate. Richard J.S. Gutman, the leading authority on diners in the country, noted that “Though a stranger, you immediately felt at home when seated at the counter alongside one of the regulars.”1 While each diner is distinct in its own regards, this feeling that can be found in each of them.

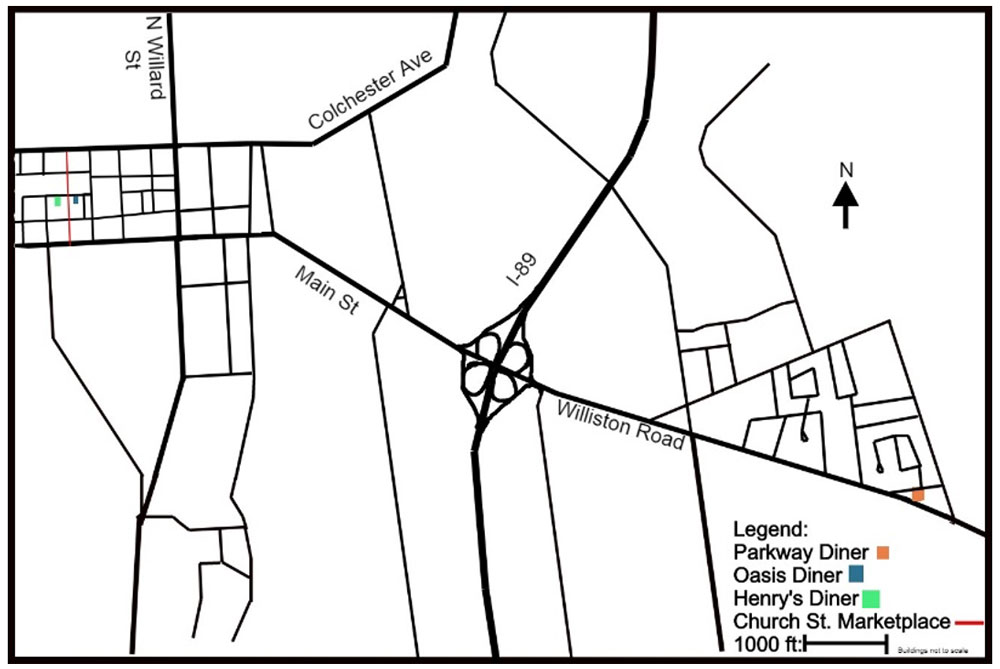

While there are many other established and iconic eateries in the area, several among them being diners, Henry’s Diner, Oasis Diner, and Parkway Diner were the best fit in regard to the scope of this research. Each started with the unmistakable design of a diner and evolved over time, letting them build their own identity despite starting in a similar style. Henry’s Diner and the former Oasis Diner are located on Bank Street in Burlington, VT, putting them within a block of the Church Street Marketplace. The third diner – Parkway Diner – is located near the intersection of Williston Road and Kennedy Drive/Airport Road. Each of these diners have unique traits that provide nourishment for those who visit, going beyond the basic goal of a diner by providing the intangible things that only a diner can offer.

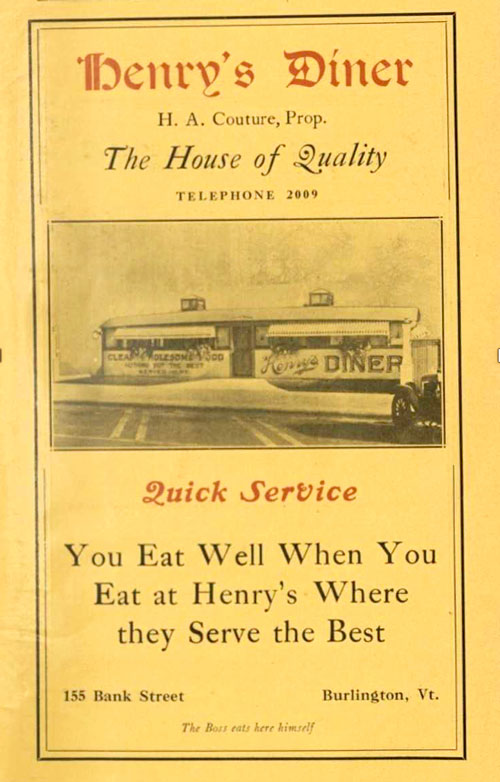

Henry’s Diner – 155 Bank Street, Burlington, VT

Brief History

There can’t be a comprehensive look at traditional diners in this area without the inclusion of Henry’s Diner. It was built and transported by Jerry O’Mahony Inc. from Elizabeth, NJ to its Bank Street location in 1925 for Henry Couture. As the first diner to have opened in Burlington, one of the first diners in the state, and the first business to have air conditioning, Henry’s Diner has solidified its place as an iconic diner.2 Ownership changed hands at several points through the diner’s history, but it always maintained its position as an iconic diner in Burlington.

The Henry’s Diner we see today does not immediately resemble the original diner that opened in 1925, having been redesigned in a Mediterranean style with stucco walls and tile roof in 1935.3 Stepping through the front door will still give one a glimpse at the mostly original design though. The interior is considered to be “your quintessential diner in layout, with a color scheme that is unique and notable for classic Vermont diners.”4 It is even more impressive that it can retain a striking resemblance to the original design considering the damage done by a fire in 1969.5 It took a few months to get everything back in order, but the diner was restored to its former glory and has remained largely unchanged since, proving the resilience of Henry’s Diner.

While ownership changes and structural damage throughout the nearly 100 years of business might seem like they would significantly alter Henry’s Diner, many things stayed consistent. There are still regulars that keep Henry’s Diner in their routine, employees who have dedicated decades of service, and patrons who form a line in front of Henry’s Diner every morning, all because it adds the nourishment they are looking for in their life.

The Social Impact of Henry’s Diner

Couture wanted to foster a sense of community and a welcoming feeling before many other diners had considered to do so, with particular regard to women. The diner movement was slow to accept women as customers because the original design of diners started with carts that were operated at hours that were more common for men to be awake. But Henry Couture was one of the first diner owners to add the touches to make diners feel more welcome to women. He timed customers to see who took the longest to decide on their order and eat; he found that women were “just as snappy as men” in a diner.6

Henry’s Diner continued to be welcoming to anyone looking for the experience of a diner, offering “food worth while, cooked as you would have it cooked, served efficiently, courteously; and the size of your check will not spoil the enjoyment of your meal!” according to an ad placed in Burlington Free Press on November 18, 1930. It’s this idea that a diner isn’t just about getting your food, but the attitude in which the food is served that separates a diner from other institutions. Restaurants can feel artificially friendly or formal, and fast food places feel emotionless while rushing you out the door. The diner tends to stand apart by striking the balance between quick service and a connection to anyone who visits, giving it an intangible benefit over other options.

While “Counter Culture,” a term used by author Erin McCormick, is not unique to Henry’s Diner, they present it in a way that other nearby diners do not.7 The markedly unique feeling at Henry’s Diner is the feeling of being at ease and at home when you’re there. This feeling remained consistent no matter who was the current owner of Henry’s Diner – although many of these owners might have added to the overall feeling – and comes more from the memories that could only be built in a long-standing business. Many intimate moments are shared in a diner, the memories of first dates stirred for some while employees and customers alike refer to it as a “home away from home.”8

It doesn’t matter if one grew up in Burlington and became a regular at the diner or if someone is a college student who is stopping by for the first time, Henry’s Diner is the kind of place you’ll feel welcomed. A lot might have changed at Henry’s Diner, and a lot might change in the future, but you can be sure that feeling will stay, and that is one of the factors that makes diners so appealing to a broad range of people. Consistency in feeling and homestyle meals will never go out of style.

The sociability and welcoming feeling of Henry’s Diner seems to stem from the familiarity that only a business as established as this can instill. The sense of family tends to go both ways, certainly making customers feel welcomed but also helps those that work there. This type of support between people fosters nourishment in a way that many businesses overlook. This might be the reason that so many servers and cooks choose to stay with a diner for so long, or why so many customers make a point of coming back whenever they are in the area; no matter the reason, it won’t be difficult to find someone to have a candid conversation with in Henry’s Diner.9 A general sense of comfort and warmth are usually associated with feeling at home, which are feelings that can be associated with a good condition that supports nourishment.

Oasis Diner – 189 Bank Street, Burlington, VT

Brief History

The Oasis Diner was shipped from Mountain View Diners in New Jersey up to Burlington, VT and continues to sit on the location that it landed in 1953.10 Harry Lines was the original owner and buyer, with the Lines family operating the diner from when it opened in 1954 up until 2007 when it was sold to Gerry Walter. Walter repurposed the Oasis Diner into a New York style Deli called Sadie Katz Delicatessen.11 In 2011 the diner was sold again, this time reopened as El Cortijo Taqueria Y Cantina. 12

The design of the Oasis Diner had not changed much while it remained open. Only a handful of businesses were able to stay open in the Church Street area for as long as Oasis Diner had, and none of them remained as unchanged as the Oasis Diner. The minimal interior updates included changing upholstery, everything else was kept as original as possible.13 Consistency and reliability are a few of the key things that kept patrons of the Oasis Diner happy, along with another distinct topic of conversation that comes up at this diner: politics.

The Oasis Diner became a place for customers, workers, and even prominent politicians to discuss politics in both formal and informal ways.

Although one might find some of the same appeal of Henry’s Diner at the Oasis Diner, but, as with every diner, the Oasis Diner has its own character that draws a crowd. The narrow design and stools that overlooked the food prep area made it is easy for customers and employees to have a conversation, even when there is a lot going on. At the Oasis Diner, “regulars are welcomed like old friends, and a stool at the counter is often earmarked” for the regular that is expected to arrive.14

When Stratton “Stratty” Lines owned the diner, his passion for politics worked its way in. While this might seem like a turnoff for some customers, it fueled many more to find their way into a booth or onto a stool. There’d often be truck drivers coming in with the sole idea of arguing with Stratty while others would just come in to watch the debate, making for an entertaining and informative experience whenever time was spent at the Oasis Diner. “There are three reasons I go there: the food, the prices, and the entertainment” noted one regular customer of the Oasis Diner, making it clear that politics did not bother him.15

The noted political conversations distinguish Oasis Diner from other eateries in the area. You will rarely hear a restaurant being praised for political debates between the owner and customers, but this is something that’s not just acceptable at a diner, it’s expected. Stratty was able to balance working, talking, and running the diner, and gave the Oasis Diner a feeling and tone that other diners just didn’t have.

The political notoriety of the Oasis Diner is thought to have started with former Governor Phil Hoff being the diner’s attorney. This notoriety grew into something bigger than the diner would have ever expected.

It was said that “a Democratic candidate who campaigns in Burlington almost always makes a stop at the Oasis Diner…” so that they could talk with Stratty and the Oasis Diner crowd.16 This helped solidify the importance of Oasis Diner in its community, drawing movie stars and even the President of the United States to its doors.

With President Bill Clinton coming through the doors in 1995 during his visit to Burlington, the Oasis Diner became a Democratic stronghold. Clinton sat with Senator Patrick Leahy and Representative Bernie Sanders, having the street outside cleared by security and the guests who were already inside approved to stay. While other eateries might feel uneasy or anxious with notable people coming in, the Oasis Diner continued like a normal afternoon. This was part of the beauty of the Oasis Diner; people from all walks of life will come and go while the staff makes sure everyone is taken care of and comfortable. Just as it would after any other customer, the booth was wiped down once the President left and the ebbs and flows of the day continued.17

While it might have gotten a partisan reputation, David Lines, owner after Stratty, said that they want to “consider it a democratic place with a small ‘d’.” Staying as democratic as possible opened up many opportunities for discussion and personal growth for those inside the Oasis Diner. The debate was always friendly and fostered a sense of comradery among visitors, Bill Post, a regular at the Oasis Diner, had said “You can talk about politics, sports, anything else that’s going on… You meet all kinds of people and you make friends” at the Oasis Diner.18

The expanded definition of nourishment calls for elements that allow for growth and good condition, which is what would be found at the Oasis Diner. Being able to grow as a person means being able to accept multiple points of view, debate their merits, and come out either reinforcing the original thought or having it rethought. Jon Lines was an owner that supported growth, urging that everyone will be respected for their opinion at Oasis Diner and that it won’t make anyone think less of anyone else. That the “spirited discussion” won’t make anyone less of friends by the time the finish their meal. Even Senator Leahy recognizes the importance of the Oasis Diner in this regard, admitting “…I learn more here than I do when I take a poll.”19

Parkway Diner – 1696 Williston Rd, South Burlington, VT

Brief History

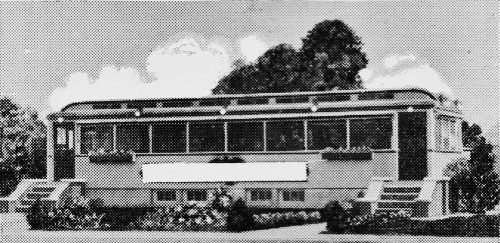

Constructed in 1953 and opened in 1955, the Parkway Diner came from the famous Worcester Lunch Car Company. The Parkway Diner is number 839 in the long list of diners that the Worcester Lunch Car Company designed, giving it every traditional feature expected from a diner. It was originally purchased by Gus and George Lines, then was sold to George Hatgen in 1975. Hatgen ran it until 1990 when his son took over for nearly seven years. At the end of that seven years, the son decided to lease the Parkway Diner to George and Christine Alvanos who renamed it the Arcadia Diner. After the lease ended, the diner was bought by Corey Gottfried who restored the diner’s original name and is currently the owner.20

The design of the Parkway Diner is almost entirely unchanged from the day it landed on its site. The most major change is that it recently had an addition built onto the back for a kitchen due to safety protocols and the need for more space while working. Gottfried made sure the historic value of the building remained, making the only marked difference being that customers wouldn’t be able to watch their food being made anymore.21 A modern innovation to help remedy this was installing televisions behind the counter and cameras so that staff and visitors could still interact even though they were separated by a wall. 22

While the Parkway Diner doesn’t have the same downtown location as either of the previous diners, it is located in a spot that draws a lot of attention. The Williston Road location, being right around the corner form the airport, brings a variety of people eager to see what this classically designed diner offers. The Parkway Diner is unique in that it blends many of the traits that the other two diners have. Being located away from the downtown area makes it more of a jack-of-all-trades while the previous two had characteristics that they seemingly focused on. The combination of social and political discussions, as well as a lively and entertaining team, marks the Parkway Diner as a nourishing place.

A Blend of Iconic Diner Traits

The convenient location makes it understood why people are drawn to the glinting design of this diner, but there is much more than that to keep customers interested. It’s easiest to start by answering the question that so many have asked: Why come to the Parkway Diner?23

A good starting point would be to look at the connections customers have with the diner. Someone who helped put the foundation on the diner when it arrived in the 1950s continued to go here for breakfast. Others recognize the homestyle of food and it brings back memories of when they were growing up in their family home. Some regulars have the specials memorized so that they know which day has their favorite foods.24 It’s the feelings that come from these stories and memories that keep someone coming back, letting them relive those moments every time they visit.

Another possible reason to visit is that the Parkway Diner has stayed close to its original. From the original owners up until the newest, each has worked hard to ensure the original feeling is maintained. No matter if updates were needed or if parts were replaced, the work being done always kept as close to original as possible. Some owners even ordered parts from New Jersey – referenced as the “diner capital of the U.S.” – so that each part matched the rest of the diner.25 Other owners have gone on record saying “I never redecorate, just clean,” and this dedication is not in vain as the traditional look encourages those who drive by to stop for a meal.26 With many people turning to new experiences as a way to keep their life exciting, choosing to come to a diner like the Parkway Diner is a fulfilling feeling.

Looking further, we can add the team at the Parkway Diner to the list of reasons that people continue to come in. Diners are known for having servers who are happy to have conversation with customers, but it is the employees’ disposition that truly distinguishes a diner from anywhere else. A server who once worked at Parkway Diner mentions how “It’s not so much how fast you are, but how your attitude is… If a customer comes in ugly, you can try to make them leave happy, and most of the time it works,” which sums up the culture of a diner and how it can provide nourishment in a variety of ways.27 There is a sense of friendliness through the urgency of needing to record and deliver orders, which seems to be a specialty for the team at the Parkway Diner.

The attraction to the Parkway Diner continues to build further than the design and team. The Parkway Diner is a place that people can relax while working and contemplating new ideas. The atmosphere of the Parkway Diner makes it common for tech innovators to scribble ideas on napkins while having their morning coffee.28 Being able to feel comfortable and at ease allows someone to focus on the task at hand, and being able to know that a diner can be the place for that speaks volumes about the sense of community that the diner creates. There have even been congressional candidates choose the Parkway Diner for their morning drinks and contemplations.29

Each visitor at the Parkway Diner shows that it’s a place that nourishes not only the body, but the mind as well. With a memorable and timeless design that has been upheld for over half a century, staff that seems to truly care about how someone is doing when at one of their tables, the nostalgic feelings a diner brings back for the regular crowd, and thoughts and ideas that flow freely, the Parkway Diner more than satisfies the criteria of what it means to be a nourishing place.

The Qualifying Traits of a Diner as a Nourishing Place

A list of nourishing places would be incomplete without including diners. Even though owners come and go, building designs might be altered, or surrounding landscapes might change, the diner stays consistent. The friendly atmosphere and expedited service draws in customers without regard to social structure, putting each on a stool to rub elbows and talk about whatever the most pressing – or least pressing – issues are at the time. From Presidents of the United States all the way down to the most common person, a diner has something for anyone.

Diners are an establishment that have stood the test of time by being resilient in the face of change. Even just looking at the three diners researched for this project, each has seen political unrest from wars, economic instability, and varying degrees of ownership changes, yet, the buildings still stand. Diners can be used as a shelter to weather some of most difficult times in the country by offering people the kind of nourishment that will help them remember the good times that have passed and those that are yet to come. Diners have proven that they can adapt to the changing needs of their communities while keeping their warm and welcoming atmosphere.

People were drawn to diners after devastating September 11th attacks. The uniquely American feeling of a diner was something that people rallied around. The sense of community and togetherness that’s built in a diner can’t be found elsewhere, and it brought comfort to a large group of people. Many noted that a diner is “a place that knows and welcomes you” and that the people coming in “feel a sense of closeness in diners.”30 The nourishment for the mind and soul that a diner offers can help soothe even the most restless of times.

“To a degree, a diner is a state of mind – a unique combination of equipment, food and people efficiently shoehorned into a tiny space.”31 Simplifying a diner to each of its parts won’t give the full view of what they can offer. It is easy for a business to have friendly employees or regular customers, it is easy to be able to serve food, and it’s easy to make a building stand out from the ones around it, but it is not easy to put it all together. The beauty of a diner is that it has genuine friendliness that isn’t forced, food that can transport you back to a favorite memory, and a design that’s been meticulously maintained for decades. All of these facets come together to make the diner a place that “you will be treated like family. You will enjoy home-cooked, made-from-scratch meals in a laidback, causal setting.”32

When considering nourishment, consider a definition that is more expanded than food: consider all the things that make you feel good. A diner is a place that caters to those good feelings, making anyone and everyone feel welcome. Diners provide a more intimate experience than fast food without the formalities of a restaurant, putting them securely on the list of nourishing places.

Notes

1. Richard Gutman, Diners: Then and Now (HarperCollins, 1993), 170.

2. National Register of Historic Places, Church Street Historic District, Burlington, Chittenden County, Vermont, 2010, https://www.burlingtonvt.gov/sites/default/files/PZ/Historic/National-Register-PDFs/Section7_ChurchStNRDistrict.pdf.

3. “Henry’s Diner in New Design Opens Tomorrow,” Burlington Free Press, June 11, 1935, 5, newspapers.com.

4. Erin M. McCormick, Classic Diners of Vermont (The History Press, 2018), 104.

5.“Henry’s Diner Extensively Damaged by Fire,” Burlington Free Press, September 2, 1969, 13, newspapers.com.

6. Gutman, Diners, 84-91.

7. McCormick, Classic Diners, 16.

8. Adam Lisberg, “Time slips away for Henry’s Diner,” Burlington Free Press, October 15, 1999, 1A, 4A, newspapers.com.

9. Daniel Laskin, “Henry Couture Founded Henry’s in 1925; How It’s Changed,” Burlington Free Press, June 16, 1975, 15, newspapers.com.

10.Ted Tedford, “Diner Serves as an Oasis in time,” Burlington Free Press, 18 September 1987, 1B, newspapers.com.

11.Tim Johnson, “Oasis Diner sold; new owners to open deli,” Burlington Free Press, October 2, 2007, 1A, 9A, newspapers.com.

12. Sally Pollak, “Taqueiria to replace Katz on Bank st. in Burlington”, Burlington Free Press, November 12, 2011, 7A, newspapers.com.

13. Sam Hemingway, “End of the line for oasis owner,” Burlington Free Press, Jult 5, 1996, 1A, 16A, newspapers.com.

14. Melissa Pasanen, “Diner Democracy,” Burlington Free Press Weekend, October 26, 2006, 14-16, newpapers.com.

15. Hemingway, “End of the line,” 16.

16.Scott Mackay, “Political People Make Sure the Spotlight Shines on Candidate,” Burlington Free Press, June 1, 1980, 1B, 12B, newspapers.com.

17. Debbie Salomon, “Turkey, Pie – and the meal of a lifetime,” Burlington Free Press, August 1, 1995, 1A, 4A, newspapers.com.

18. Shawn Turner, “A Diner Looks at 50,” Burlington Free Press, January 24, 2004, 6A, newspapers.com

19. Turner, “A Diner Looks at 50,” 6.

20. McCormick, “Classic Diners,” 114.

21. Joel Banner Baird, “Owner aims to beef up safety, efficiency at iconic diner,” Burlington Free Press, November 14, 2014, 4A, 5A, newspapers.com.

22. Sally Pollak, “TV-to-Table at Parkway Diner,” Seven Days, March 6, 2020, https://www.sevendaysvt.com.

23. Sky Barsch, “Diners say goodbye to diner,” Burlington Free Press, March 26, 2007, 1B, 3B, newspapers.com

24. Debbie Salomon, “Diner takes things over easy,” Burlington Free Press Weekend, January 24, 1991, 18, newspapers.com.

25. Melissa Pasanen, “Parkway open again,” Burlington Free Press, October 24, 2007, 10Y, newspapers.com.

26. Salomon, “Diner takes things,” 18.

27. “A Day in the Life of Sue Devino: Waitress”, Vermonter, July 22, 1984, 8, newspapers.com.

28. Nancy Bazilchuk, “Burlington excels at innovation,” Burlington Free Press, December 9, 2001, 6E, newspapers.com .

29. Danica Kirka, “Guest running hard for congressional seat,” Brattleboro Reformer, August 9, 1988, 3, newspapers.com.

30. Debbie Salomon, “Diners bring camaraderie, comfort,” Burlington Free Press Weekend, September 20, 2001, 7, newspapers.com .

31. Doug Adrianson, “Diners,” Vermonter, August 27, 1978, 2, newspapers.com.

32. McCormick, “Classic Diners,” 15.

Nourishing Places: Some Historic Restaurants in Bernardsville and Basking Ridge, New Jersey

By Marcella Hain

Bernardsville: The Town History

Bernardsville was originally a section of Bernards Township known as Vealtown. In 1840, Vealtown became Bernardsville, named after Sir Francis Bernard, Colonial governor of New Jersey from 1758 to 1760. Nestled in the northernmost part of Somerset County, just twelve miles south of Morristown, New Jersey, this rustic community sits in some of the last vestiges of the Great Eastern Forest. After the Civil War, many wealthy and prominent New Yorkers moved into the area, first as summer visitors, then as permanent residents of the Bernardsville Mountain.1

It was late in 1871 that the railroad reached Bernardsville, the last stop on the line for twenty years. It brought the man who changed the town’s character completely. He was George I. Seney, President of the Metropolitan Bank of New York. He loved the area, and he and his friends came and stayed. Then began the construction of the large mansions and estates, many of which still exist, and the creation of the whole “mountain” society, slowly at first but reaching a crescendo in the 1890s and early 1900s.2

With the railroad came the summer colonists. Attracted by the beauty of the hills, the healthful climate, easy connections with large cities, and a dearth of mosquitoes, financiers and the socially elite made Bernardsville a ‘posh’ resort area.3 Where but a few years previous to this period there were only two streets other than main roads in Bernardsville and suddenly everything changed. Local homes were crowded with boarders and worker shacks became common. In time these newcomers, too, found the community a good one and Bernardsville was on its way into the modern age. A suburban community now, it has been separated from Bernards Township since 1924.4

These buildings that presently stand under their current names, The Station, Rudolph’s Steakhouse, The Grain House, began as nourishing places at the dawn of railroad or car culture, and continue to this day because of their adaptability as the decades rolled along.

The Station

The Claremont Hotel was built circa 1878, shortly after the railroad was extended in Bernardsville with a station built directly across the street. A past owner put the construction date at 1878 based on markings on the old barns behind the hotel. However, a local historian, Edwin S. Spinning (1875-1970), believed the original owner, Bob Van Dorn, secured the Thomas Bird property and remodeled it into a hotel in the mid-1890s. The Claremont Hotel catered to traveling salesmen and those looking for less expensive options other than the luxurious Bernards Inn just down the street. The bar and office were located on the first floor and the second and third floors held the guest and dining rooms, approximating a total of 20 hotel rooms. The Claremont Hotel also hosted civic gatherings. Men concerned about fire safety in the area met there in October 1897, to create the Bernardsville Bucket Brigade, the precursor of the Bernardsville Fire Company.

In 1905 the Claremont Hotel was enlarged, and the exterior underwent some significant changes. A large porch was added with Greek columns, and a side entrance was created facing Claremont Road adjacent to the main building. The hotel also garnered a new name along the way; the West Bernards Hotel. In June 1905, its name was changed again to The Claremont.

The hotel continued until 1923 when Bernardsville plumber Alfred D. Sutton (1880-1954) purchased the building and renamed it “The Claremont Apartments.” Sutton converted the first floor into three stores and the upper floors into six apartments. Sutton did a complete renovation; improving the interior, the plumbing, and provided wash tubs, baths and other modern updates including heating. The businesses that came and went on the first floor included Sutton’s plumbing business, a barber shop, car showroom, antique shop,5 even a chiropractor.6

In 1954, Robert Vallacchi purchased the building from Sutton, recreated a bar and dining area on the first floor, transferred a liquor license from the nearby Wagon Wheel Tavern, and christened his new place The Townhouse Cocktail Lounge, featuring “entertainment” Wednesday through Saturday nights. 1968 brought about a new remodeling project where the bar was embellished with antique birch paneling and a large central rectangular bar installed. The Townhouse Cocktail lounge continued to be popular with the locals as well as area softball teams. The building changed hands in 1972, and then again in 1976, when it was given its current name, The Station. In 2000, The Station changed hands again, in 2006, the large bar was removed and more tables moved in, giving it a new look and a new name: The Station Pub & Grub. Unfortunately, business slumped for the restaurant. It was closed, the rectangular bar brought back, seating areas made more open for dancing, ceiling-to-floor windows added, and the bar opened once again as The Station in May 2013, and has survived the current pandemic by offering outdoor dining. The building itself continues to have six apartments upstairs, and round the back, facing Claremont Road, the Penguin Ice Cream parlor continues to be a local favorite.7

Rudolph’s Steakhouse

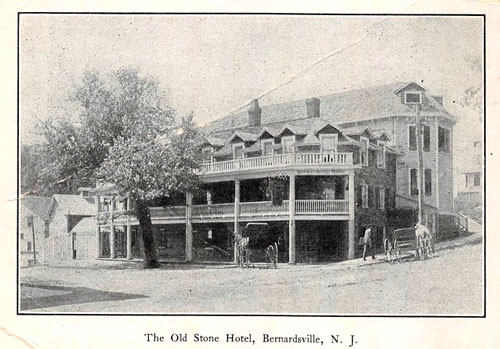

The latest incarnation of the building that began as the Old Stone Hotel is now Rudolph’s Steakhouse. The original building started out rustically while travel in the region was mainly by horse or foot.

This three-level structure was built in 1849 using stone from local quarries as thick as a yardstick. While it was originally intended to be a blacksmith’s shop, it became the Old Stone Hotel and was operated under owner John Beck. The hotel had a matching horse stable across the street which operated until 1905 when it was demolished. In 1882, owner Lewis Doty built a rear addition.8

W.H. Lyon, who renamed the building the Bernardsville Hotel, owned it through the 1900s. Lyon’s untimely death in a car crash, at the age of 30, in 1909 led to a change in ownership.9

By 1910 it once again came to be known as the Old Stone Hotel. Governor Woodrow Wilson, (later President of the United States), arrived in Bernardsville in an 11-car motorcade on Oct. 20, 1911, to promote Democratic candidates. Wilson and his and 48-member entourage lunched at the Old Stone Hotel before he gave a speech just steps outside at Olcott Square. A few short years later and the hotel was struggling. A lack of patronage caused its closure in September 1918 and it did not reopen until May 1921. By then, Prohibition was in full swing. In 1928 hotel owner Killian Reusser was jailed on charges that he “dined and wined” several prohibition enforcement agents.10

From the Bernardsville News:

Killian Reusser, proprietor of the Old Stone Hotel here, was held in $1,000 bail for the grand jury Monday afternoon in Newark after being arraigned before United States commissioner Friedmann on a charge of sale and possession of liquor. The hotel keeper was hauled in after three polished men had ‘dined and wined’ in his hotel, and after getting the drinks, kindly informed Reusser they were prohibition enforcement agents. When first asked to supply the intoxicants Reusser was reluctant, but after being assured that his guests were ‘good fellows’ he set out the glasses and obliged. The good fellowship was followed by the command that Reusser accompany the trio to Newark to see the ‘Judge’.11

In September 1929, the establishment was again in trouble with the law, and a U.S. District court ordered the Old Stone’s bar padlocked for allegedly selling whisky. Fortunately, Reusser was allowed to keep renting out hotel rooms. The same family continued to own the hotel until Roswell Reusser (1911-2005), the son of Killian, sold it in 1961.12

Roswell Reusser was a World War II veteran, as his engagement announcement proudly states: Roswell Reusser, in his engagement announcement to Virginia Happe, is listed as being a graduate of Valley Forge Military Academy of Pennsylvania. He spent two years overseas as a paratrooper in the 101st Airborne Division in Europe. Mr. Reusser is owner of the Old Stone Hotel in Bernardsville. (1946-12-26)13

By the 1960s and early 1970s, the Old Stone Hotel only served dinner on special occasions such as St. Patrick’s Day, and continued to provide 15 guest rooms. New owners later in the 1970s planned to install a lounge, game room and dance floor as well as provide lunch and dinner. Michael Lyons took over the place in 1978, renovated the building and renamed it Freddy’s, after the fictitious western prospector Frederick T. Fasbuck. Lyons discontinued the hotel rooms and planned to have entertainment four nights per week. Lyons wanted to undo the Old Stone Hotel’s unsavory reputation and attract a different crowd. Nicholas Novello bought Freddy’s in 1982, and Sunday comedy nights became a thing around town. Among the rising stars who performed at Freddy’s were young comedians such as Jerry Seinfeld, Eddie Murphy, Rosie O’Donnell, Paul Reiser, Chris Rock and Gilbert Gottfried. The performers had a tiny stage at the front of a room that held about 75 people.

With changing times Novello had the restaurant renovated in 1996 and it re-opened as the Old Stone Tavern and Brewery, offering its own beers brewed on site. The brewing equipment was installed at the former stage where bands and the comedians had performed. Another change of the guard brought with it the name, Bernardsville Stone Tavern and Brewery. When it closed in 2006, extensive renovations were made to give the building a more upscale environment and a name chosen to reflect the equestrian clientele. In 2007, the newly christened Equus drew rave reviews for its décor, but its fine dining menu gained a reputation as being overly expensive. The economic meltdown of 2008 could not have come at a worst time for a fledgling restaurant, and Equus closed in 2012. The building remained vacant until 2014 when a New Yorker took it over and opened it as Caballo, an upscale Mediterranean restaurant with a Spanish twist.14

This incarnation lasted approximately two years. Established in 2016, Rudolph’s Steakhouse and Tavern advertises a curated cuisine that pushes traditional flavors to new heights, giving the community a modern and unexpected take on classic American cuisine.15

Fingers crossed!

The Grain House

An idea conceived by William Childs, in an area of Basking Ridge that was part of Bernardsville until 1924 and historically called “Log Town” became what is now known as The Grain House.

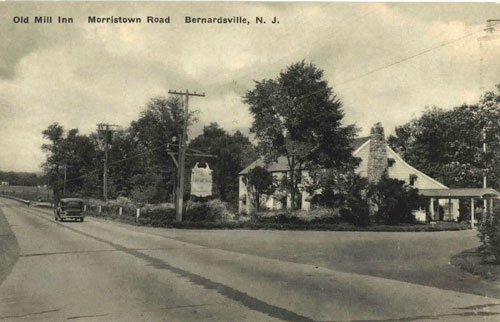

Legend has it that the Grain House Restaurant was at one time a barn used to store the grain that fed George Washington's Revolutionary Army during their winter encampment of 1779–1780, just up the road at Jockey Hollow. In 1929, respected restaurateur William Childs purchased the Van Dorn Mill, which included the fabled grain barn. The Childs family at the time were famous for their national chain of restaurants up and down the East Coast, at one point owning over 100 eateries.16

In a marvelously successful decision, Mr. Childs moved the old barn standing nearby the mill across Route 32 (now Route 202) and made plans to renovate it as an inn: The barn roof and sides were gone but the structure was firm and he decided it could be renovated. It was moved across the road and converted to the Old Mill Inn. In restoring the barn, not a beam was touched by saw or axe. Despite its age the frame was still solid. None of the lines of the classic old structure have been changed.17

To convert the Grain House barn into an inn, William Childs made the following changes: the wagon room was renovated for dining, the horse stable was turned into a grill room, the grain storage room was turned into the current Grain Room, and the haymow upstairs became seven small bedrooms and baths that were used into the 1970s as hotel rooms. These sleeping rooms originally even featured historic "rope mattresses". The Olde Mill Inn began serving food in the 1930s and the Childs family owned the property until 1952.18

Soon after opening, the restaurant was exceedingly popular. From a newspaper article in 1931: Although much thought and effort was given to the creation of Old Mill Inn, little did William Childs, one of the founders and for many years head of the famous chain of restaurants bearing his name, dream that this old structure, painstakingly remodeled and with the very soul of early America contained in it s hand-hewn beams, would within a few weeks of the time it was opened as a public eating house fail to meet the demands of its clientele. However, an appreciative patronage, including residents of Essex, Bergen, Sussex, Morris Union, Passaic, Hunterdon, Middlesex and Mercer and many of the southern counties soon made the demands for table accommodations so great that it was necessary to re-arrange the first floor in order to provide added accommodations.19

Experience had taught Childs that a “suitable location was the most important single factor in the success of a restaurant”.20 The roads were being paved with cement and improved; car culture was coming to New Jersey.

From an account on the history of the Somerset Hills: According to historians, Route No. 202 was formed by linking together a number of roads passing close to places of historic interest from Maine to Delaware—in this area Washington’s Headquarters in Morristown, Jockey Hollow, Bedminster and Pluckemin. In the early 1920s the most heavily travelled roads in the area, known as State Highways No. 31 and No. 32 were paved with concrete. They are now designated U. S. Highways No. 202 and 206.21

There were other subsequent owners of the property, and a separate building was added in 1977, to be used as a hotel, as a venue for large social events, and as a full-service conference facility. As the years went by, the establishment changed hands several times, and by 1993, the Inn, including the restaurant, had deteriorated due to mismanagement and was nearly in ruin. The Bocina Group bought the place in 1993 and after renovations, re-opened the establishment, renaming the “Old Mill Inn” as "The Grain House" in 1994.22

While the Olde Mill Inn occupies a place in the history of the Somerset Hills, it also embraces progressive ideas. Founder William Childs, ahead of his time, was an early proponent of vegetarian cuisine.23 The Grain House, as well as the adjoining Inn, have pioneered new ideas and practices regarding healthy natural cuisine and have also been early adopters of many innovations to create environmentally friendly buildings and sustainable practices for the preservation of the environment.24

Notes

1. Bernardsville, a history, Borough of Bernardsville, accessed 11/10/2020, https://www.bernardsvilleboro.org/pages/bernardsville-a-history.

2. J. H. Van Horn, Historic Somerset, (New Brunswick: Somerset County Historical Society, 1965), 30.

3. L. Mott Schuylar...[et al.], Among the blue hills—Bernardsville: a history (Bernardsville, NJ: Bernardsville History Book Committee, 1974), 160.

4. Van Horn, Historic Somerset, 31.

5. W. Jacob Perry, “Station Pub building holds major place in B'ville history,” Bernardsville News, January 16, 2016, https://www.newjerseyhills.com/bernardsville_news.

6. “Dr. Harold T. Phyliky Licensed Chiropractor,” Bernardsville News, 14 May 1925.

7. Perry, “Station Pub,” 2016.

8. W. Jacob Perry, “Basking Ridge, Bernardsville landmarks to reopen,” Bernardsville News, April 11, 2014, https://www.newjerseyhills.com/bernardsville_news.

9. “William H. Lyon Killed,” Bernardsville News, 3 December 1909.

10. Perry, “Basking Ridge, Bernardsville landmarks to reopen,” 2014.

11. “Local Man Held In Bail,” Bernardsville News, 6 December 1928.

12. Perry, “Basking Ridge, Bernardsville landmarks to reopen,” 2014.

13. “Virginia Happe Roswell Reusser,” Bernardsville News, 26 December 1946.

14. Perry, “Basking Ridge, Bernardsville landmarks to reopen,” 2014.

15. Rudolph’s Steakhouse & Tavern, From this business, History, Yelp!, November 10, 2020.

16. Carly Kilroy, “The Olde Mill Inn and The Grain House Celebrate 20 Years,” The Patch, June 10, 2014, https://patch.com/new-jersey/baskingridge/.

17. Valerie Barnes, “A history concerning two farm boys, Samuel and William Childs,” (Unpublished manuscript, December 25, 1976), 7, Clippings, Family File 1925-1997, Childs Family Folder.

18. Kilroy, “The Old Mill Inn,” 2014.

19. “Old Mill Inn Historic in Its Location,” Plainfield, N. J. Courier-News, 21 September 1931, 25.

20. Barnes, “A history concerning two farm boys, Samuel and William Childs,” 3.

21. Schuylar, Among the blue hills, 164.

22. Kilroy, “The Old Mill Inn,” 2014.

23. Brock Pemberton: Foster Ware, “The Hand That Feeds You,” The New Yorker, April 9, 1927.

24. Kilroy, “The Old Mill Inn,” 2014.

Historic Inns of Vermont; Nourishing Places

By Marissa Gibbs

Sustained by nourishing people, hotels, inns, and bed & breakfasts have long served as places of comfort and places of nourishment for weary travelers and their other occupants alike. Throughout their history, the Willard Street Inn in Burlington, the Lang House on Main in Burlington, as well as the Green Mountain Inn in Stowe have all served many purposes to those who have lived, visited, and worked there. Some, including the Willard Street Inn and The Lang House, were not always inns, and previously served as single family homes, and in the case of the Willard Street Inn, even as a retirement home for a period of time in its later life. Although each has been used for different purposes throughout their histories, they do have one thing in common; they are places of nourishment. Whether the nourishment was for those living in the homes, lodging there, visiting, or retiring, these homes have seen phases of nourishment, but not without the hard work of those truly sustaining these incredible structures. If it were not for the men and women who worked at each of these homes, those living and enjoying the comfort of the homes would not have been nourished in the way they were.

Throughout this research a main focus was to bring light to the hardworking people who cooked, cleaned, repaired, and even served as seamstresses or coachmen to the owners of these homes. Although history has the unfortunate habit of not including the narratives of those who were in the working class, that does not diminish the importance of these individuals and the roles they played in creating and sustaining such beautiful homes and businesses. While reporting on the general history, architectural styles, and ownership of these homes since their creation, the names and occupations of those men and women who have worked in these places will also be discussed. Without their work, these structures would simply be walls and rooms with no warmth and purpose.

Willard Street Inn, Burlington, Vermont

The Willard Street Inn, located at 349 South Willard Street in Burlington, was built for Charles Woodhouse, a bank worker, business man, and government leader, when he was around the age of 46 in 1881.1

This Colonial Revival/Queen Anne combination style mansion was designed and built by A.B. Fisher, a Burlington-based contractor.2 Charles Woodhouse was born in 1835 to Charles Woodhouse and Lepha Lucinda Guernsey in Brattleboro, Vermont.3 After a successful business career and climbing the ranks of the banking industry, Charles Woodhouse had become very wealthy and commissioned a house to be built that matched his wealth and status. This brick structure, located on the 1.16 acre corner lot of South Willard and Spruce Street in Burlington, stands at two-and-a-half stories, and boasts massive steep-pitched roofs and a large portico covering the double-door entrance.4 The home itself has an expansive interior of 13,482 square feet, with fourteen bedrooms and fifteen bathrooms, making it a truly grand structure for Charles and his family.5

Along with his wife, Emma Easton Day, and his surviving son, Lorenzo E. Woodhouse, the home had many live-in workers who helped with the upkeep of the home and the transportation of the family.6 Dennis McDonald, a young man born in Vermont in February of 1860, appears on the record of the Woodhouse residence in 1880 at the age of 22 as the Woodhouse’s coachman.7 Dennis was of Irish descent, with both parents immigrating to America from Ireland.8 Dennis worked for the Woodhouse family as the coachman for around thirty years, appearing on all census records at 349 South Willard from 1880-1910.

Agnes Flannery, born in Vermont in 1862, worked for the Woodhouse family as a cook from around 1900 to 1910, most likely until closer to 1914 when Charles Woodhouse died of a heart attack at the age of 79, leaving his wife Emma as a widow.9 Agnes was also of Irish descent, with both of her parents being born in Ireland before immigrating to America before Agnes’ birth.10 Kate Flannery, most likely the younger sister of Agnes, appeared to join the Woodhouse residence as a seamstress around 1910 at the age of 44.11 She was also born in Vermont, with two parents from Ireland, and from having the same last name and being listed as such in the 1910 federal census, it is likely that she was related to Agnes.12 Like Agnes, Kate worked for the Woodhouse family for a number of years, most likely continuing until or slightly after Charles Woodhouse’s death in 1914. Census records and the Burlington directory show Emma Woodhouse remained the owner of the home at 349 South Willard, however, in 1920 she was recorded as a lodger at the Hotel Buckingham in New York.13 As shown in the 1924 Burlington directory, Emma returned sometime between 1920 and 1924 to the Willard Street residence, where she died on January 4th, 1924 at the age of 92.14

With Emma Woodhouse’s death came the sale of the home in 1925 to Loring R. Stinson, who was the manager of the Porter Screen Company.15 Loring Stinson remodeled much of the original residence, adding elements such as the large enclosed brick extension where an original one-story porch used to be, and a grand brick staircase off of the brick porch addition.16 These elements remain to this day, and add to the grand feeling of the mansion. Along with Loring Stinson’s wife Anna Regina Fink, by 1930 two other people were living in the residence, Mary Cescone and Frank Cescone, who were employed by the Stinson’s as a cook and a gardener, respectively.17 Both Mary and Frank were born in Italy, with Frank having immigrated to the United States in 1888, and Mary in 1892.18

In 1944, the home was sold to Costas Economou and his wife Dorothy (Katchianes) Economou.19 Costas, whose full name was Constantine Papaeconomou, and Dorothy were cheese manufacturers at the E. Economou cheese corporation in Hinesburg, Vermont.20 Costas was originally from Greece, after which he emigrated from Montreal, Canada to Vermont and became an American citizen in April of 1943.21

In the late 1960s and into the 1970s, the property at 349 Willard Street was privately owned and went through multiple attempts made by private owners and the Champlain College board to change it into dorms with off street parking for Champlain College or a private apartment building. In 1969, the zoning board of the city of Burlington denied the zoning request made by Champlain College to transform the former Woodhouse mansion into a dormitory for 50 students with additional off street parking on the lot.22 Burlington’s zoning board claimed that the plan would be disruptive to the neighborhood and that the area should remain residential.23

In the following years, Joseph and Beverly Wool proposed their plan to rezone the mansion into a four apartment home, but this was ultimately denied as well by the zoning board of Burlington.24

In 1982, the property was transformed into a retirement home by the name of Willard Heights.25 The retirement home served the community of Burlington and provided a comfortable place for the elderly of the community to spend their days. After fourteen years in business, the Willard Heights retirement home was purchased by Lakeview Associates, and the property was once again transformed.26 This time, however, the property was remodeled to nourish the community in a new way as a bed and breakfast. After seeing numerous families grow, many employees tending to the growth of the families, and most recently elders of the community being cared for within its walls, the structure at 349 South Willard Street began to nourish the community, as well as visitors from far and wide. Champlain College and University of Vermont parents, visiting friends, and any traveler were all welcome to stay in the once prestigious halls of the home. The house has maintained its grandeur, and the renovations done in the following years from 1996 by Gordon and Beverly Watson allowed the house to be back in its original state of splendor.27 From then it served as an inn for the community, changing ownership in 2005 when the Davis family took over operations of the inn.28

To this day the Willard Street Inn sees many faces pass through its doors, and it goes without question in saying that it has become a nourishing place for all, which is with no doubt because of the earnest, kind, and passionate individuals that have worked to make it so.

Lang House on Main, Burlington, Vermont

In 1881, John McLaughlin, a well-known builder, constructed this Queen Anne style home on Main Street in Burlington for Frank Dudley.29 McLaughlin drew plans for the home from William Comstock’s 1881 pattern book, using these plans for both the interior and exterior design.30 Soon after in 1883 the home was purchased by Jonas G. Reed (J.G. Reed), a wealthy tobacconist, and the house came to be known as the Reed House. The two-and-a-half-story home has all of the significant Queen Anne architectural elements, from the “fishscale pattern” slate roof to the intricate woodworking detail on both the exterior and interior of the home, indicative of the rise in machine woodworking of the era.31 Jonas Reed grew his wealth through climbing up the chain in the tobacco wholesale business, starting out as a traveling tobacco salesman, working for the firm of Murray and Reed, of which he was a member.32 In 1884 he became the senior partner in the firm (now of the name Reed & Taylor), and in 1895 Jonas became the sole proprietor.33

J.G. Reed lived in his home with his wife, as well as Melvina Alexander, who is listed on the census records as the Reed’s “servant,” and Frank Coyne, who was the family’s coachman.34 Melvina, although simply listed as a “servant,” undoubtedly held many roles within the home, as the term servant is very broad as well as degrading in today’s society. She most likely assisted the family with any household needs that may have arisen, such as cooking and cleaning, and perhaps any other upkeep needed, or any other tasks that Mr. or Mrs. Reed may have needed. Melvina, at the time of the 1900 census, was 31 years of age, had been married for 10 years, and had two children of her own.35 Frank Conye, the family’s coachman, was born in Vermont in 1869, and was 30 years old at the time of the census.36

On March 30th, 1910, J.G. Reed died at the Hotel Bancroft in Washington D.C., leaving his wife Jane a widow, who continued to live in the house on Main Street until it was sold in 1923.37 During the time Jane Reed lived in the home, it was reported that she employed Maria Chambers to perform the duties of a house maid.38 Maria was 54 years old at the time of the 1920 census, and cared for the home until the change in ownership in 1923.39

From the time of its construction, the house had been addressed at 370 Main Street, and remained as such until the address was shifted to 360 Main Street in 1923.40

Later owners included the Grout family, consisting of Aaron and Edith Grout and their two daughters, Eleanor and Nancy, as well as Frederick W. Van Buskirk, an X-ray physician at the Bishop DeGeosbriand Hospital in Burlington, which is now a part of the University of Vermont Medical Center.41

In the mid-1970s, Lang Associates Real Estate purchased the home and set up their office within its walls.42 The home had now turned its course to a different sort of nourishment, one that would serve others in finding their own home through the work of the individuals who were employed at the Lang Associates office.

In 2000, the home at 360 Main Street underwent renovations to transform it into the 11-room bed and breakfast that it is today.43 Permits began to be issued to the Lang House on Main Street to update security and safety features within the building.44 Soon, the house would turn its course yet again, and serve to nourish the community and its visitors. After operating under this new management for three years, the property was yet again turned over to a new owner, this time to a woman by the name of Kim Borsavage, who continued to maintain the original beauty of the home while creating a nourishing space for visitors from near and far to stay while they explore the city of Burlington.45 Kim Borsavage owns and operates the Lang House on Main to the current day, and the building has continued to be an exemplary image of Queen Anne architecture and 19th and 20th century history.46

A recent visit to the Lang House on Main offered a wonderful opportunity to see some of these details up close, proving that the intricate woodwork and thoughtful designs of the builder have been reverently maintained and displayed for all guests to experience.

Green Mountain Inn, Stowe, Vermont

The Green Mountain Inn, known previously as the Mansfield House and the Mount Mansfield Hotel, is a 19th century federal style brick structure built in 1833 for Peter C. Lovejoy.47 Unlike the other two homes, this building served as a hotel/inn for most of its lifetime. The main block of the hotel is the original structure, which was built as a home for Peter C. Lovejoy, and stands at two and a half stories with a simple four bay plan.48 Peter soon traded his home for farm land outside of Stowe, and the ownership of the house was passed to Stillman Churchill, who added the two brick side wings onto the main block of the house.49 Stillman Churchill opened his home to the public as the Mansfield House, but after a mortgage foreclosure caused Churchill to lose the property, W.H.H. Bingham became the new owner of the Mansfield House.50 While the building existed as the Mansfield House, it served the public as a place to come to dance in the dance hall added by Stillman Churchill and enjoy their time with friends and family.51 The community was given a place to gather, and the purpose of the building only changed slightly when W.H.H. Bingham turned it into the Mount Mansfield Hotel.52

In 1880 the hotel was under new management of Edwin C. Bailey and William P. Bailey, a father-son duo that renamed the building to the Brick Hotel and employed a staff of sixteen workers during the time they operated before another transfer of ownership in 1893. During these years, all of the hired help worked to create a nourishing place for the community and its visitors by taking care of the hotel and its guests through each of their jobs. Harry D. Brown, a man of the age of twenty at the time of the 1880 census, worked as the hotel’s clerk. John Kelly, a man originally from Ireland, worked as the hotel’s head waiter, with Katie Ravy as another waiter, and Kate A. Brahana as the table maid. Frederick Hennamode, an immigrant from Germany, also worked in the food service portion of the hotel as the kitchen’s pastry cook. Wilkinson E. Field worked at the hotel as a bar keeper. From his death records, it seems that he continued to work at the hotel, having had his last occupation listed as “hotel clerk.” Among the many general workers in the hotel were Julia Young and Isaiah Debray, two Canadian immigrants who were listed as workers in the hotel on the 1880 census. Two chamber maids, Mattie Ingals and Katie E. McMahon, were listed on the census as well, and both were born in Vermont and in their twenties when the census was taken. It is important to bring these names to light, as they are often glazed over when researching historic sites such as hotels and other public-serving businesses. Owners names are always known, while the workers who gave their time to make the business as successful as it was are not usually mentioned. These individuals are the reason that the hotel could run as a functioning business, and they should be celebrated for their hard work and dedication to their jobs. There was one boarder in the hotel that was enjoying the fruits of the worker’s labor in 1880 by the name of Moses Desell, a blacksmith from Canada.53

In 1893, the inn was purchased by Mark C. Lovejoy, who was the grandson of the original owner, Peter C. Lovejoy.54 Mark renamed the Brick Hotel into the name it is known as today, The Green Mountain Inn.55 Lovejoy ran the inn with the help of his brother, Lewis P. Lovejoy, who served as a hotel clerk, and four more employees that made up the staff of the new inn.56 Members of his new staff included Max and Etta Haselton, Celia Pareizo, and Esther Marshall, with Max Haselton listed as a hotel clerk, and the remaining three listed as “servants” at the inn.57 There may have been others employed by the Lovejoys at the time, performing jobs such as cook, waitress, and chambermaid, and it is also possible that the individuals listed as “servants” were the ones performing all of these odd jobs around the inn. Overall, it is these employees work that created a well-functioning inn that survives to this day.

Around 1911 the Inn came under the management of E.W. Webster, who looked after the inn for about a year and a half until the management was passed from E.W. Webster to Mr. and Mrs. E.E. Bamforth in 1912.58 In 1916, the inn was sold by Mark C. Lovejoy to Cornelius L. McMahon, who purchased the property to be managed by F.S. Boardman.59 In 1917, McMahon sold the Green Mountain Inn to Mrs. W.E. Burt, who purchased the business to be run by A.A. Hunter.60 By 1920 the Inn was yet again under new management, until the property was purchased by the Bodman family from Massachusetts.61 The Bodman family owned and managed the Green Mountain Inn until 1944 when they sold the property to move back to Massachusetts.62 Robert L. Knight of Providence, Rhode Island was next to own the property located at 18 Main Street in Stowe, and while he was the owner of the property, the business was fully managed by Addie and Harriet Sawyer, a mother and daughter who oversaw all aspects of the day to day functions of the Inn.63 In 1947, the Inn was turned over to Richard H. Gaylord who moved from Northfield, Vermont to purchase and take ownership of this historic hotel.64 It was not until 1982 when Marvin Gamerhoff, a wealthy man from Canada, purchased the Inn, and it has been the property of the Gamerhoff Trust since 1982.65 Gamerhoff has contributed much of his own wealth to the renovations and restoration of the hotel, and has donated some of his historic purchases, such as wood purchased from the historic Chittenden County Courthouse in 1982, to organizations such as the Vermont Historical Society, while continuing to use these historic elements in his own renovations of the Inn as well.66

The Green Mountain Inn has nourished the public for over 150 years, and continues to do so as the structure is continuously maintained and updated to meet the needs of current day travelers. The history is not lost on the modern hotel, however, as the history and the appreciation of the inn’s past is apparent in the care taken to maintain the architectural and historical value of the property. Throughout their years, each structure has served a multitude of purposes, from that of a home, a place to retire and rest, and most recently as places of nourishment in the form of hotels and inns. These buildings are each exemplary displays of historic architecture, as well as wonderful illustrations of personal histories bringing a structure to life. Without the work put in by the employed individuals, the houses would not be homes, the businesses would not flourish, and the hotels, bed & breakfasts, and inns would not nourish the communities to their fullest potential. The names of those who have given these spaces their ability to nurture relationships and foster healing and wellbeing of their inhabitants need to be brought to light, and it is imperative that they do not get forgotten when studying the history of the buildings that communities such as these have grown to love.

Notes

1. “The Story of Your Innkeepers & The Inn,” Willard Street Inn Bed & Breakfast Mansion, accessed November 11, 2020, https://www.willardstreetinn.com/our-story.

2. Conard, Diane, et. al., “South Willard Street Historic District,” National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1988).

3. Barb Destromp, “Charles Williamson Woodhouse (1835-1914) - Find A...,” Find a Grave, December 10, 2007, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/23351498/wo.

4. “Willard Street Inn,” CIRCA Old Houses, September 15, 2020, https://circaoldhouses.com/property/willard-street-inn/.

5. Ibid.

6. Charles W Woodhouse. Year: 1880; Census Place: Burlington, Chittenden, Vermont; Roll: 1343; Page: 53B; Enumeration District: 066

7. Ibid.

8. Ibid.

9. Charles W Woodhouse. Year: 1900; Census Place: Burlington Ward 5, Chittenden, Vermont; Page: 14; Enumeration District: 0071; FHL microfilm: 1241690; Charles W. Woodhouse. Year: 1910; Census Place: Burlington Ward 6, Chittenden, Vermont; Roll: T624_1613; Page: 11A; Enumeration District: 0073; FHL microfilm: 1375626; Charles W Woodhouse. Vermont State Archives and Records Administration; Montpelier, Vermont, USA; User Box Number: PR-01925; Roll Number: S-30913; Archive Number: M-2073436.

10. Charles W Woodhouse. Year: 1900; Census Place: Burlington Ward 5, Chittenden, Vermont; Page: 14; Enumeration District: 0071; FHL microfilm: 1241690

11. Charles W Woodhouse. Year: 1910; Census Place: Burlington Ward 6, Chittenden, Vermont; Roll: T624_1613; Page: 11A; Enumeration District: 0073; FHL microfilm: 1375626

12. Ibid.

13. Emma E Woodhouse. Year: 1920; Census Place: Manhattan Assembly District 15, New York, New York; Roll: T625_1212; Page: 8A; Enumeration District: 1049

14. Emma E Woodhouse. Vermont State Archives and Records Administration; Montpelier, Vermont, USA; User Box Number: PR-01925; Roll Number: S-30913; Archive Number: M-2073436; Emma E Woodhouse. Year: 1924; City: Burlington, Vermont, U.S. City Directories, 1822-1995.

15. “City News,” Burlington Free Press, February 23, 1925, page 12.

16. Conard, Diane, et. al., “South Willard Street Historic District,” National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1988).

17. Loring R Stinson. Year: 1930; Census Place: Burlington, Chittenden, Vermont; Page: 17B; Enumeration District: 0023; FHL microfilm: 2342161

18. Ibid.

19. “C. Economou Buys Former Woodhouse Residence in City,” Burlington Free Press, 6 September 1944, 4.

20. “Miss Martha Helen McSweeney is Married to Dean Economou,” Burlington Free Press, 20 February 1967, 5.

21. Costas Economou. National Archives at Boston; Waltham, Massachusetts; NAI Number: 595941; Record Group Title: Records of District Courts of the United States, 1685-2009; Record Group Number: RG 21

22. “Champlain College Plea Before Zoners Tuesday,” Burlington Free Press, 1 August 1969, 14.

23. “Zoners Reject Appeal By Champlain College,” Burlington Free Press, 6 August 1969, 3.

24. “Burlington Zoning Board of Adjustment Public Hearings,” Burlington Free Press, 13 April 1971, 21.

25. “Willard Heights; Retirement Home for Gracious Living.” Burlington Free Press, 28 April 1982.

26. “City of Burlington, VT,” Property Database, accessed November 11, 2020, https://property.burlingtonvt.gov/Details/?id=7943.

27. “The Story of Your Innkeepers & The Inn,” Willard Street Inn Bed & Breakfast Mansion, accessed November 11, 2020, https://www.willardstreetinn.com/our-story.

28. Ibid.

29. “The Inn’s History,” Lang House on Main, accessed November 11, 2020, https://www.langhouse.com/about-us.html#history.

30. Ibid.

31. Carris, David, et. al. “Main Street-College Street Historic District,” National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1988).

32. “J.G. Reed & Co.; A Leading and Long Established House in the Tobacco Trade,” Burlington Free Press, 26 January 1907, 43.

33. Ibid.

34. Jonas G Reed. Year: 1900; Census Place: Burlington Ward 3, Chittenden, Vermont; Page: 1; Enumeration District: 0069; FHL microfilm: 1241690.

35. Ibid.

36. Ibid.

37. “Obituary; Jonas G. Reed,” Burlington Free Press, 31 March 1910, 8; University of Vermont, “University of Vermont,” Historic Burlington: University of Vermont, 2004, http://www.uvm.edu/~hp206/2004 1890/burlington1890/website/dcolman/main/?Page=360.html.

38. Jane L Reed. Year: 1920; Census Place: Burlington Ward 1, Chittenden, Vermont; Roll: T625_1871; Page: 11A; Enumeration District: 43.

39. Ibid.

40. University of Vermont, “University of Vermont,” Historic Burlington: University of Vermont, 2004, http://www.uvm.edu/~hp206/2004 1890/burlington1890/website/dcolman/main/?Page=360.html.

41. Aaron H Grout. Year: 1930; Census Place: Burlington, Chittenden, Vermont; Page: 2A; Enumeration District: 0007; FHL microfilm: 2342161; Frederick W. Van Buskirk. Year: 1948; City: Burlington, Vermont, U.S. City Directories, 1822-1995.; University of Vermont, “University of Vermont,” Historic Burlington: University of Vermont, 2004, http://www.uvm.edu/~hp206/20041890/burlington1890/website/dcolman/main/?Page=360.html;UVM Medical Center, “The University of Vermont Medical Center,” The University of Vermont Medical Center (blog), November 6, 2014, https://medcenterblog.uvmhealth.org/community/history-legacy-bishop-degoesbriand/.

42. “The Inn’s History,” Lang House on Main, accessed November 11, 2020, https://www.langhouse.com/about-us.html#history.

43. Ibid.

44. The City of Burlington, “City of Burlington, VT,” Property Database, accessed November 11, 2020, https://property.burlingtonvt.gov/Details/?id=7814.

45. “About Us,” Lang House on Main, accessed November 11, 2020, https://www.langhouse.com/about-us.html#about.

46. Ibid.

47. Lisa Ryan and Paula Sagerman, “Stowe Village Historic District,” National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 2002).

48. Ibid.

49. “Inn History,” Green Mountain Inn, accessed November 11, 2020, https://greenmountaininn.com/inn/inn-history.shtml.

50. “Inn History,” Green Mountain Inn, accessed November 11, 2020, https://greenmountaininn.com/inn/inn-history.shtml; Lisa Ryan and Paula Sagerman, “Stowe Village Historic District,” National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 2002).

51. Ibid.

52. Ibid.

53. William P Bailey. Year: 1880; Census Place: Stowe, Lamoille, Vermont; Roll: 1345; Page: 486D; Enumeration District: 129; Wilkinson E Field. Vermont State Archives and Records Administration; Montpelier, Vermont, USA; User Box Number: PR-01920; Roll Number: S-30728; Archive Number: M-1991800

54. “Green Mountain Inn Sold-Will Be Run by F.S. Boardman,” Burlington Free Press, 11 September 1916, 5.

55. “Inn History,” Green Mountain Inn, accessed November 11, 2020, https://greenmountaininn.com/inn/inn-history.shtml.

56. Mark C Lovejoy. Year: 1900; Census Place: Stowe, Lamoille, Vermont; Page: 4; Enumeration District: 0136; FHL microfilm: 1241692.

57. Ibid.

58. “Stowe; Progressive Rally and Flag Raising to Take Place Thursday,” Burlington Free Press, 2 October 1912, 13.

59. “Green Mountain Inn Sold-Will Be Run by F.S. Boardman,” Burlington Free Press, 11 September 1916, 5.

60. “Buys Stowe Hostelry; Green Mountain Inn Sold to Mrs. W.E. Burt of Burlington,” Burlington Free Press, 3 December 1917, 2.

61. “Green Mountain Inn Sold by Bodmans,” Burlington Free Press, 4 September 1944, 4; “Stowe; Funeral of H. Bertrand Faunce Held at Late Home-Village Notes,” Burlington Free Press, 29 September 1920, 8.

62. Ibid.

63. “Green Mountain Inn Sold to R.H. Gaylord,” Burlington Free Press, 4 November 1947, 3.

64. Ibid.

65. “Inn History,” Green Mountain Inn, accessed November 11, 2020, https://greenmountaininn.com/inn/inn-history.shtml.

66. “Auctioneer’s Hammer Descends On Old Courthouse Interior,” Burlington Free Press, 20 December 1982, 13.

Examining Historic Town Squares in North Georgia

By Connor Plumley

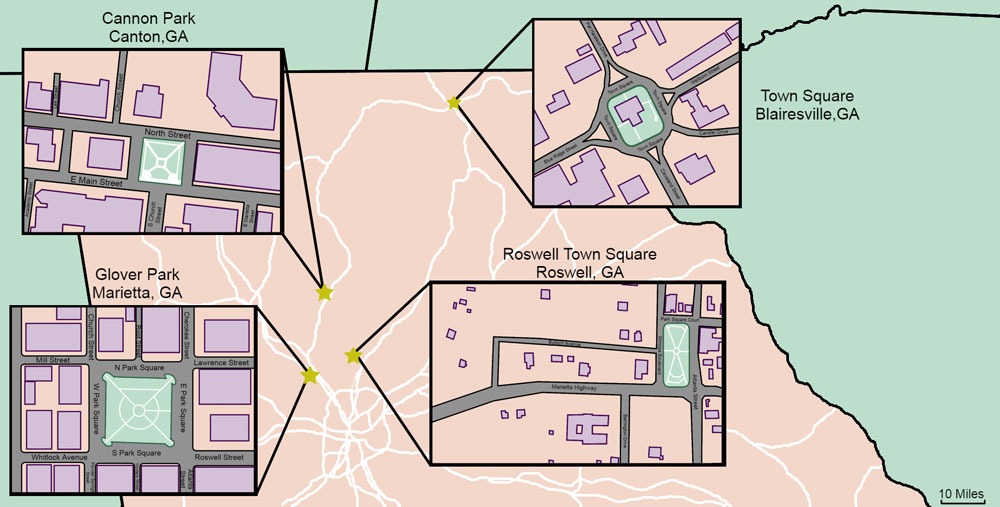

The classic image of the main street setting in a small town is a quintessential piece of Americana. It is a concept, given physical form, around which communities can gather and form a collective sense of identity. Even in today’s busy world, it is such an important concept that many historic districts are built around a town or city’s “Main Street” and across the country these districts are being revitalized. But what of town squares? In many cases these serve a similar, if not identical, role to that of a main street in fostering this sense of community. From this point I will be examining the role of town squares in providing a source of cultural nourishment using examples from Blairsville, Canton, Marietta, and Roswell, Georgia as case studies. For the purpose of this study I will focus primarily on Marietta’s Glover Park; not because it is more significant than the others, but rather because it combines each of the elements that define the others.

Courthouses

The common element that links the town squares of Blairsville, Canton, and Marietta comes in the form of their respective county courthouses. Built in 1899, Blairsville’s Union County Courthouse stands in the center of the town square in stark contrast to the much newer stores, restaurants, and lodging that surround it. By the 1970s it had fallen into such disrepair that the original clock tower was no longer standing and the building itself was no longer in use. Despite this, the courthouse meant enough to the local community that in 1976 the Blairsville Jaycees would attempt to restore the old clock in a well-intentioned act that produced an end product described at the time as “both amusing and educational.”1 The Union County Historical Society would eventually have more success in preserving the courthouse than did the Jaycees, seeing the courthouse added to the National Register of Historic Places as the Old Union County Courthouse in 1980. The clocktower has since been restored by the historical society and the courthouse now serves as a museum.2

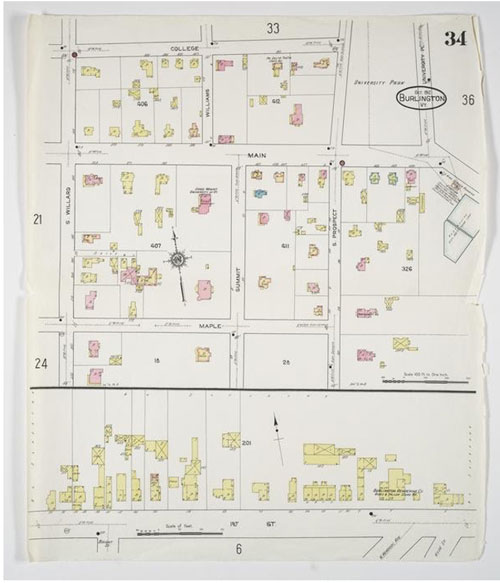

The relationship between Canton, Georgia’s courthouses and town square is less straightforward than in Blairsville. It can be determined from a 1921 Sanborn Insurance Map that Canton’s town square is located where the Cherokee County Courthouse once stood.3 It is worth noting that the courthouse shown on this map is the second courthouse at this location, with the first courthouse being destroyed when the town was burnt by federal troops in 1864 as retaliation for the hanging of Union soldiers by Confederate scouts.4

The second courthouse would burn in 1927, leading to the construction of a third courthouse on the lot immediately to the north and the conversion of the original lot to a town square. The third courthouse still stands and was added to the National Register in 1981, though it is now used as a museum by the Cherokee County Historical Society. In a letter attached to the National Register nomination, the President of the Cherokee County Historical Society states that the courthouse had “been the heartbeat of this county since it was built” and goes on to point out the added significance of the use of native marble in the building’s construction given the importance of the marble industry in the county.5 This courthouse/museum features prominently on the square, as does the current courthouse.

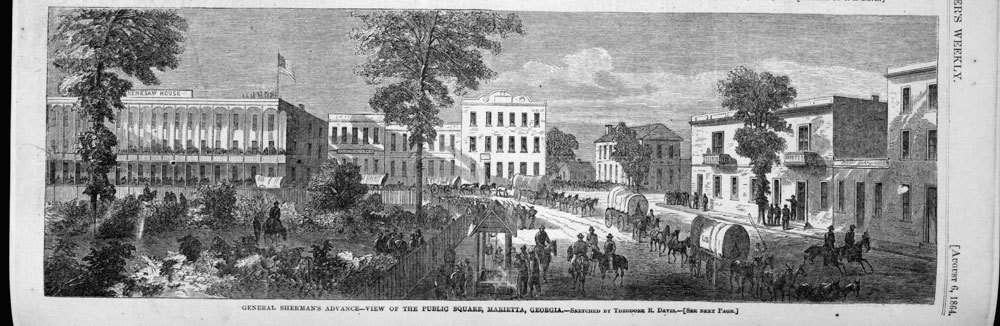

The history of the relationship between Marietta, Georgia’s town square and courthouses is much closer to that of Canton than it is to that of Blairsville. As in Canton, Marietta’s town square was once the site of the county courthouse, only for the lot to be established as a public park in 1852 after the original courthouse was lost in a fire. Marietta has since had three courthouses on the square, each occupying the city block immediately to the east of the square. The second courthouse would play an abhorrent role in the community, serving as a place to auction slaves as late as 1863 when a notice for the sale of an enslaved woman and child ran in a local newspaper.6 The second courthouse was destroyed the next year after General Sherman began his famous March to the Sea.7 The third courthouse was demolished in 1966 to make way for the current courthouse complex, the last major change to a town square otherwise described as a “throwback in time.” 8

Each of these courthouses, both surviving and long since destroyed, may not have nourished their respective communities in a traditional since, but they both figuratively and literally laid the groundwork for what the squares would come to represent. In the early years of these communities the courthouse squares represented something around which the communities build; they were quite simply the center of each community. Restaurants, banks, hotels, pharmacies, clothing stores, hardware stores and more sprang up around the courthouses.9 Beyond this, in continuing to function as museums as they have in Canton and Blairsville, the courthouses are providing a way to nourish and enrich today’s communities by housing their history and giving them a place to study it, learn from it, and continue to grow together.

Theaters

Canton’s town square and Marietta’s town square share another key element with the presence of notable theaters. The Canton Theater, previously known as the Bonita and later the Haven Theater, dates to 1911 but was remodeled to an Art Deco style in the 1930s and 1940s. It is a contributing structure in the National Register listed Canton Historic District. Despite early success, the theater fell into disrepair after a decline in popularity in the 1970s. The theater was purchased in 1994 by a person who hoped to restore both the theater’s structure and its role in the community, stating his desire for the theater to become a “focal point.” This development was set “the whole town… buzzing.”10 The restoration was successful enough for the city to purchase the city in 1997.

Marietta’s Strand Theater, an art deco theater built in 1935 and initially closed in 1976, followed a path that paralleled the Canton Theater. The Strand Theater played a significant role in the community and was met with excitement upon its opening, with newspapers detailing outings such as a socialite hosting a theater party as a “complementary gesture to her daughter” in 1935.11 The Strand closed as a theater in 1976 but would continue to play a role in in the community as it faced several decades of uncertainty, with its uses over the next thirty years including that of a draft house and later a non-denominational church. The pastor of the church noted that he had attended movies at the Strand as a child.12

In 2003, an organization known as the “Friends of the Strand” began pushing the idea of renovating the Strand, with some in the community pointing to the newfound success of the Canton Theater. The early plan for this project would include seeking donations from the public. At the time the idea was presented in 2003, one person expressed his hope that “the Strand could be something really special. It could be the gem of Cobb County.”13