The Crystal Lake Falls Historic District is historically significant under National Register Criteria A because of its role in the industrial history of Barton, of northeastern Vermont, and of the State of Vermont.

Beginning in 1796, and continuing through the 1940s, the natural waterfalls

of the Crystal Lake Outlet (also historically known as the Barton River

or branch of the Barton River) were the sites of Barton's numerous manufacturing

and milling establishments. These enterprises were constructed here to take

advantage of the power that could be generated from the falls. The mills,

workshops, and factories, as well as the other associated buildings in the

district, document the evolution of Barton's industrial economy. Starting

with small, owner-operated mills which served the needs of the surrounding

agricultural economy, industrial production grew dramatically in the mid

19th century after the railroad connected Barton with major urban areas.

Large, out-of-state firms took advantage of Barton's water power to develop

industries that processed local and imported raw materials into finished

products which were exported throughout the country. At its peak in the

first quarter of the twentieth century, Barton was one of only a few communities

in the northeastern part of Vermont whose economy was dominated by industry

rather than agriculture or forestry.

In general, early European American settlement of towns in northern New

England was focused near rivers suitable for hydro-powered mills. These

mills were essential to the initial development of the town, processing

raw materials such as grain and logs into food and shelter supplies. Soon

after towns established stable populations, some old grist and saw millswere

converted and several new mills built to process various raw materials and

agricultural products for market. For example, grist and saw mills would

be accompanied by nineteenth-century fulling mills, carding mills, machine

shops, carriage shops, blacksmith shops, and specialty woodworking shops.

These mills evolved and manufactured new products as the demands of the

regional and global economic markets changed through the years. For example,

saw mills tended to evolve into specialty woodworking shops and blacksmith

shops were converted into foundries.

While this general pattern for settlement and evolution of towns throughout

Vermont and northern New England can be found in most town histories, social

and economic trends during the twentieth century have altered or totally

replaced these former mill districts in many towns. Of those towns which

still contain remnant historic mill districts, few have mill districts as

extensive and intact as that of Barton. The historic district includes a

mix of abandoned ruins and buildings currently used commercially or as residences.

Today, these properties provide the community with historic continuity,

in terms of their physical presence and in terms of their ongoing use in

the community.

The Crystal Lake Falls Historic District is also significant under National

Register Criterion C as a distinguishable nineteenth and early twentieth

century industrial community with significant architectural examples of

industrial buildings, worker's housing, and associated stores,public buildings,

service buildings, and dam sites. The primary historic context reflected

by the district is Small Water Powered Mill Production as identified in

the Vermont State Historic Preservation Plan. Property types represented

include mills, dams, water races, archaeological sites, and workers' houses.

Other historic contexts identified in the State Preservation Plan which

pertain to the significance of the Crystal Lake Falls Historic District

include: Commercial Development in Rural Areas, Railroads, Manufacturing

of Agricultural Implements, and Building Materials Manufacturing. The property

types found in this district that reflect the first of these contexts include

stores, mill buildings and mill sites, while the freight depot reflects

the second. Archaeological resources may also support the historic contexts

of Manufacturing of Agricultural Implements and Building Materials Manufacturing.

The industrial significance of the district is demonstrated by the Small

Water Powered Mill Production historic context. Water-powered manufacturing

dominated the economic and social life of Barton from the 1790s through

the 1930s. The numerous industries that tapped into the 2,000 available

horsepower provided employment and the basis of the local economy. The surviving

grist mill (#43) and woodworking establishments (#44, #46 and #51) most

strongly reflect this context.

The falls of Crystal Lake (known by the French as Belle Lac and early settlers

as Bellewater Pond) were developed as a power source soon after the town

of Barton was settled in 1796. The first grist mill was built the following

year by Asa Kimball. This had one run of stones. In 1798, Kimball built

a sawmill at the upper falls (#29). He then built a larger grist mill in

1809 with two runs of stones and a mechanical elevator to lift the grain.

This mill was located at the falls just below the West Street Bridge (#41).

Seven or eight years later, Kimball sold the mill to Col. Ellis Cobb. Cobb

had established a fulling mill at the falls in 1803. Ten years later he

started a wool carding mill, housed in a 15 by 15 foot building. By 1830,

the outlet to Crystal Lake supported a potash works, where fertilizer was

extracted from wood ashes, a tannery, and a clover mill, where local clover

crops were processed for their seed. Ten years later, the town had two saw

mills, a grist mill, a fulling mill and a woolen factory.

With the arrival of the Passumpsic and Connecticut Railroad in 1858, Barton

was connected to the urban centers of Boston, Montreal, New York, and Quebec

City. The railroad gave the town access to markets and raw materials well

beyond its borders. By taking advantage of the abundant power available

from the Crystal Lake Falls and relatively inexpensive local labor, out-of-state

companies soon established factories here. Although lumber was one local

raw material transformed into manufactured goods, other raw materials were

imported by rail. Textiles from cotton grown in the South were sewn into

ladies underwear at the Peerless Manufacturing Company (#29). Iron from

various sources was forged into plows, stoves, and machinery at the J. W.

Murkland Company (#50.)

The first of these new factories was Walter Heyward Company of Fitchburg,

Massachusetts. In 1859, only a year after the establishment of a rail connection

to Barton, the company built a sawmill at the first falls. Soon the company

expanded its operations to produce wooden chair parts. These parts were

then shipped to Massachusetts for finishing. In the 1870s, the company supplemented

the power of the falls with the installation of a steam engine, insuring

that power could be generated even in times of light water flow. By the

1880s, the company employed 35 to 40 men at its factory, but in 1890, the

Heyward Company experienced financial difficulties and left Barton.

The establishment of the Heyward Company in Barton represented the beginning

of a general trend in Barton. Initially, Barton's industries served local

needs. Sawmills produced lumber for local use and the grist mills, tanneries,

and carding mills transformed raw agricultural materials into products for

local consumption. With the industrialization of the post-Civil War era

and the development of a national railroad system, however, Barton's abundant

power and inexpensive labor were soon tapped by industries that pulled rural

Barton into the web of the national and international economies. Mirroring

the industrial growth of the community was a growth in population. In 1850,

the entire Town of Barton had 987 residents. By 1870 the number of residents

had grown to 1,911.

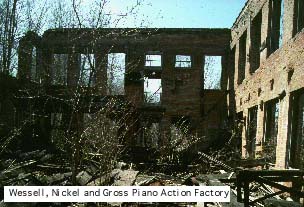

The first industries of this new generation were the woodworking establishments.

By 1868, Barton had two sawmills, two shingle mills and three shops that

produced window sashes, doors and blinds, in addition to the Heyward chair

factory. Many of these woodworking firms were clustered around the fourth

dam (site #48) of the outlet to Crystal Lake. These firms made a variety

of products including carriages, wheels, furniture, toilet seats, piano

actions, and bowling pins. The largest of these operations was the Wessell,

Nickel, and Gross piano action factory. From 1922-23 to 1940, this factory

produced the wooden actions for pianos used by many of the country's leading

manufacturers. Its brick and concrete buildings were the most modern industrial

buildings in Barton and were the last to be constructed along the outlet

to Crystal Lake. Destroyed by fire in the 1952, the ruins of the main factory

buildings remain (site #51).

In addition to these woodworking industries, John W. Murkland's machine

shop on Water Street, which opened in 1876, transformed iron, steel and

coal into iron plows, sugar arches, and stoves sold throughout New England.

Other products included cider presses, drills, planers, spool machines and

candy making machines that were distributed throughout the continent. By

the 1920s, the Murkland Company had passed its peak. The demand for its

products fell as the competition from large-scale machinery firms and foundries

proved too great. This firm ceased to operate by 1940. Murkland's machine

shop was demolished in 1970. The Chronicle newspaper office building

(#5) now stands on the site of its foundation.

Barton's third major industry was the manufacture of cotton undergarments.

In 1892, the Peerless Company of Newport, New Hampshire, constructed a large,

two-story, wooden factory straddling the outlet stream near the first dam

(#27) at the former Heyward Company site. At the peak of production, the

Peerless Company employed 200 women (mostly sewingmachine operators paid

by the piece) and about fifty men who generally cut cloth, shipped goods,

and maintained the machinery. This marked the first major industry in the

area to employ large numbers of local women. To provide for this work force,

new houses, tenements, and group boarding houses for young women were constructed

in the vicinity of the factory. (See sites #18, #19, #22, #36, & #39.)

The Peerless Company was Barton's largest employer until the 1920s. By employing

a significant number of localwomen in industrial production, it had a profound

influence on the social history the community.

During the 1920s, however, changing women's fashions and the development

of silk undergarments reduced the market for cotton underwear. The Peerless

Companyclosed its Barton factory in 1924. This closing marked the beginning

of the decline of manufacturing in Barton. When the Heyward Company left

Barton, the Peerless Company arrived to more than fill the gap, but when

the Peerless Company closed its Barton factory after thirty years, its replacement

was the Bray Wooden Heel Company, a smaller operation that remained only

seven years.

By the 1930s, industry at Crystal Lake Falls had substantially declined

as the national economic depression worsened. By then, Barton had also lost

the relative advantages of its resources, as industrial production modernized

nationally from mechanical to electrical power and small factories were

superseded by large industrial complexes located in urban areas.

Two facets of Barton's industry continued, however. These were grist milling

and woodworking. Based on the region's traditional economic base of farming

and lumbering, the earliest industries at Crystal Lake Falls lasted the

longest. Tower Brothers - E. M. Brown Mill, 1896 (#43), continued to grind

grain up to World War II. The Wessell, Nickel and Gross piano action factory

(#51) converted Vermont lumber into parts for fine pianos until 1940.

Today, the Crystal Lake Falls Historic District is given cohesiveness by

the relationships of its buildings, structures, and sites to the historic

industrial sites along the falls of the Crystal Lake Outlet. The Crystal

Lake Falls Historic District is significant under National Register Criteria

C for the architectural significance of its buildings. These buildings represent

a range of architectural styles and property types that reflect the major

periods of economic development in the district. Several early houses with

vernacular Federal and Greek Revival style clues probably date from before

the 1840s. These include: #7 (Owen-Pierce House, circa 1820); #9 (Spaulding-Judkins

House, circa 1840); and #31 (Badger House, circa 1830). The earliest dams

and industrial and commercial buildings built before the mid-19th century

are no longer standing however, having been lost to floods, fire or demolition.

The period of dramatic growth that started with the arrival of the railroad

in 1858 is the most significant period of the history of the Crystal Lake

Falls Historic District. It is represented by many significant buildings.

These include the Percival Cabinet Shop (#44) and the Baldwin & Drew

Clapboard Mill (#46), built before 1878. These vernacular, wooden, gable-fronted

mill buildings are typical representative examples of mid-19th century mills

in the region. Their characteristic lack of stylistic references reflects

their utilitarian function and a conservative design approach.Another historically

significant building complex is the Passumpsic & Connecticut River Railroad

Depot & Freight House and Robinson Brothers Wholesale Store complex

(#17) built before 1878. Also lacking stylistic embellishment, this structure

is typical of utilitarian wooden storage buildings built in rural Vermont

during this period. The gable-fronted J. Buswell Tenement (#25), built around

1850, is a good representative example of a vernacular Greek Revival style

tenement of the period built in wood. Unfortunately only portions of the

circa 1860 Greek Revival style Crystal Lake House (#24) survive. Much of

this important hotel was lost to fire. The best example of the Italianate

style of architecture in the district is the First Congregational Church

of Barton (#1). Built in 1874, its level of design sophistication is typical

of Protestant churches built in the more prosperous towns in Vermont during

the period.

Typical of the vernacular house designs from this period found in Vermont's

small towns are the Kimball House (#2), the I. Wyman House (#3), the G.

A. Drew House (#4), and the J. F. Taylor House (#40). All were built aroundthe

1870s. The O. V. Percival House (#10) displays hints of the Gothic Revival

style with gable front ornamented with simple barge boards.

The only example of a full rural farmstead in the district with its attached

sheds and barns is the circa 1870 G. W. Bridgeman Farmstead (#34) located

on West Street. Several other small 19th century barns are included in the

district, however. These provided shelter and feed storage for a horse and

perhaps a cow, a few pigs, or poultry raised for domestic food consumption.

The barns may also have housed horse-drawn carriages. Representative examples

include the barn attached to the Kimball House (#2), circa 1870; the Spaulding

- Judkins Barn (#9a), circa 1875; the Percival Shed (#10a), circa 1880;

and the circa 1900 barn (#33a) on West Street.

Martin's Livery (#26), circa 1895, is a significant statewide example of

a livery stable. Another important horse-drawn transportation related building

is the Congregational Church Horse Shed (#1a), which was built around 1875.

Significant examples of utilitarian storage buildings of the period are

the Lumber Shed (#4a), which was built for the J. W. Murkland Manufacturing

Company around 1890, and the Barron Barn (#38) which dates from around 1900.

The only surviving example of the Queen Anne style of architecture in the

district is the Tower Brothers-E. M. Brown Mill (#43) built in 1896. Most

of the other turn-of-the century vernacular buildings generally reflect

the Colonial Revival style in their ornamentation. These include the following

group of dwellings on West Street: the circa 1908 Dr. Arthur T. Buswell

House (#32), and two dwellings #33 and #37 and the duplex #36, all built

around 1900. Other Colonial Revival vernacular buildings from around 1900

include two duplexes (#18 and #19) located on Main Street at the south end

of the district.

The district also has several contributing twentieth century buildings.

These include the circa 1925 filling station (#28) and the Barton General

Store (#42), which was rebuilt after the Peerless fire of 1938. The final

phase of the industrialization of the Crystal Lake Falls district that occurred

from the 1920s through the 1940s is reflected in the Wessell, Nickel and

Gross Piano Action Factory ruins (#51). Today, these fire-damaged hulks

serve as poignant reminders of the industrial heritage of Barton's Crystal

Lake Falls. This site may also hold a potential to yield information on

the local industrial history through its archaeological resources. Other

potentially significant archaeological sites include each of the dam sites

along the outlet stream (#29, #41, #45, #48a, #49) and the J. W. Murkland

Company site (#50).

Of the eleven non-contributing buildings included in the district, four

are modern garages. Two historically important buildings no longer contribute

to the significance due to the extent of alterations following damage by

fires. These are the circa 1860 Crystal Lake House (#24) and the tenement

(#39) on West Street that burned in the 1938 Peerless Manufacturing Company

fire. The extensive alterations to the front facades of the circa 1940 Barton

Hardware Store (#16), and the 1909 Crystal Lake Garage (#23), preclude their

inclusion as contributing structures.

Other non-contributing buildings include #5 (Chronicle Office;circa

1870), which was moved from across the street onto the foundations of the

Murkland Machine Shop around 1970, and #12 (Hillcrest Apartments) built

in 1980. Though large, Hillcrest Apartments reflects the approximate massing

of the buildings that previously occupied the site. Also non-contributing

is the bulk feed station of the E. M. Brown Company (#13 and #13a) built

on the site of the 1893 Boston and Maine Railroad passenger station that

was unfortunately demolished in 1967. These few non-contributing buildings

do not diminish the district's ability to convey a sense of significance

or disrupt the historic scale of the district.

Through the evidence shown by the contributing historic buildings and sites

in the district, one can trace the history ofthe village's industrial development.

One can also see how the community grew in response to the increasing employment

generated by manufacturing firms that located along the falls of Crystal

Lake. This historic district, through its sites and structures,also mirrors

the historic industrial development typical statewide. As was the common

pattern of development in most towns in Vermont, the main village was established

at a site where the geography allowed the construction of water-powered

mills. Initially serving the needs of the local, agriculturally based economy,

these sites soon also became centers of commercial, civic, social, and religious

activities. As the populations of many small mill villages reached a plateau

and then declined as Vermonters moved West during the mid 19th century,

Barton Village flourished instead. This was primarily due to the abundant

and easily tapped water power potential of Crystal Lake Falls and easy access

to the railroad.

While Vermont has a number of other cities and towns that prospered during

the industrialization of the United States which followed the Civil War

(for example, Winooski, Brattleboro, Springfield, Rutland, Barre, and Bennington),

such industrial communities are relatively rare in the northeastern part

of the state. Other cities and towns in this area that developed a diverse

industrial base during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries

include Derby, Newport, and St. Johnsbury. The majority of communities in

the Northeast Kingdom retained an economy based on agriculture and lumbering

with only a few small mills to serve local needs for lumber, flour, and

wool processing. Because the industries at Crystal Lake Falls had an impact

which extended well beyond the locality, the historical significance of

Barton's Crystal Lake Falls extends to the statewide level.

The buildings and sites are given historical cohesiveness by their relationships

to the factory sites along the outlet to Crystal Lake. The contributing

buildings and sites represent mills,factories, worker housing, larger houses

of business proprietors, stores, a church, and a fire house. All of these

buildings together comprise the community that relied upon the industries

of Crystal Lake Falls for its existence.

The Crystal Lake Falls Historic District is also significant under National

Register Criteria D for its potential to yield important information in

history and prehistory. Archaeological resources could provide a potentially

significant and continuous record of the evolution of Barton's economic

and social development. This record, once considered typical, has now disappeared

in many of Vermont's towns. The archaeological remains within the historic

district provide an opportunity for detailed research of the economic and

social evolution focused on the individual mills, on the entire mill district

and on the Village of Barton. Based on historical research and preliminary

site inspections, the entire district could be considered one contributing

archaeological site until research in certain areas indicates that they

have lost their integrity. The archaeological sensitivity also extends beyond

association with European American settlement. There is a high potential

for the presence of Native American archaeological remains.

Today, the on-going preservation and restoration activities of the Crystal

Lake Falls Historical Association are helping to educate the public about

the significance of the falls in the industrial history of Vermont. Recent

efforts of the Association include saving and restoring the circa 1820 Owen-Pierce

House (#7) as a local museum. Long-term plans include stabilizing and interpreting

for the public the site of the Wessell, Nickel and Gross Piano Action Factory

site (#51).

The Crystal Lake Falls Historic District is potentially significant on the

local, regional and state levels. Locally, this research would augment and

clarify the town history. Regionally and statewide, this research would

develop anthropological models for the evolution of northern New England

towns from frontier settlements to present- day villages. These models could

be instrumental for research in archaeology and history, and could be applied

to present issues of town and regional planning for future development.