| SEARCH |

| YELLOW PAGES |

| WHITE PAGES |

| UVM HOME |

People all over the world create art without any formal training

in what to do or how to do it. Their art is often fascinating

because of the highly personal and original objects they create

using ordinary materials in inventive ways. During the 20th century

this work was discovered by the avant garde art world and by academics.

Their attempts to analyze an incredible variety of artistic production

gave rise to the plethora of names used to categorize it such

as Folk, Visionary, Naïve, Primitive, Outsider, Grass Roots, and

the art of Self-Taught artists.

People all over the world create art without any formal training

in what to do or how to do it. Their art is often fascinating

because of the highly personal and original objects they create

using ordinary materials in inventive ways. During the 20th century

this work was discovered by the avant garde art world and by academics.

Their attempts to analyze an incredible variety of artistic production

gave rise to the plethora of names used to categorize it such

as Folk, Visionary, Naïve, Primitive, Outsider, Grass Roots, and

the art of Self-Taught artists.At the turn of the century, European psychiatrists, sociologists, and artists began to study the art of criminals and patients in mental institutions in an effort to understand how art was made by people who were as free as possible from the influences of mainstream culture. The French artist Jean Dubuffet became particularly interested in what he called "art Brut,” hoping to release European artists from the restricting conventions of academic painting. Picasso’s interest in African art is well known. Miro experimented with forms inspired by the art of children. Traditional American Folk Art became popular with collectors and museums for the first time in the 1920s. A clear distinction between art created by trained artists working within the cultural establishment and objects made by those outside it was maintained until very recently.

The sheer diversity of today’s art world has broken down some

of the preconceptions widely held about "fine art" versus other

forms of creative expression. It has been proposed that instead

of viewing the artists who live and produce their art in rural

communities or urban housing projects as “outsider artists” it

is the self-contained circle of museums, galleries, and art schools

that is outside the mainstream of popular culture. New perspectives

help to eliminate the old hierarchies and enable us to better

understand the cultural continuum between self-taught artists

and artists whose work is the result of years of training and

exposure to European art traditions.

Museum and gallery exhibitions celebrating the work of self-taught

artists are now very well received by the general public. In the

United States, exhibitions have explored the wide spectrum of

art created by individuals from different ethnic communities,

particularly the work of African-American and Latino artists.

Anna Mary Robertson “Grandma” Moses remains the quintessential

American folk artist for many people but other individuals are

gaining the recognition they deserve, including Howard Finster,

Horace Pippin, and Bill Traylor. Traylor’s paintings were shown

at the Robert Hull Fleming Museum this summer in a one-person

exhibition organized by the Kunstmuseum of Berne, Switzerland,

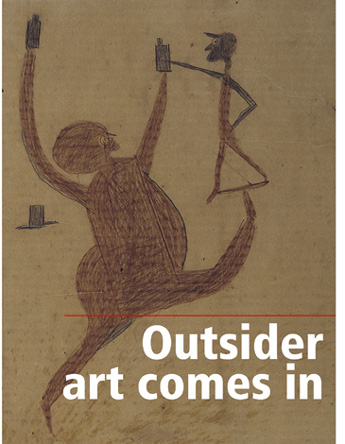

known for its interest in Outsider Art.

Bill Traylor, like Grandma Moses, discovered his artistic talent at an advanced age. In 1939, Traylor, destitute and disabled, began to draw on scraps of paper while he was seated on the sidewalk of Monroe Avenue in Montgomery, Alabama. He produced over 1,500 drawings in just three years, before he left Montgomery at the beginning of World War II. His art reflects his life experiences. Born into slavery on an Alabama plantation in 1854, he worked as a sharecropper and farm laborer for most of his life. The drawings he created depict people and animals he remembered as well as those he observed in his vicinity on Monroe Avenue. Traylor was befriended by artist Charles Shannon who promoted and preserved Traylor’s work during his lifetime and after Traylor’s death in 1949. In the 1982 landmark exhibition of African American folk art at the Corcoran Gallery in Washington, D.C. Traylor’s work was critically acclaimed, attracting the attention of art dealers and collectors. His popularity continues to grow along with his reputation as a master American artist.