|

||

| uvm a - z | directory | search |

|

DEPARTMENTS Campaign

Update LINKS

|

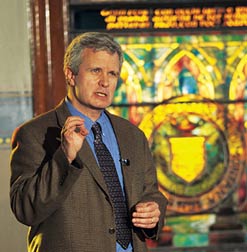

photo by Bill DiLillo

The

Origins of an Academic

Harvard Prof/UVM alumnus returns for President’s

Lecture

Tracing

one man’s personal evolutionary history, Peter Ellison ’75

recalls his first encounter with Charles Darwin’s The Origin of

Species. “It stopped me in my tracks. I had never encountered anything

so powerful in my life,” he says. Ellison, founder and principal

investigator of Harvard University’s Reproductive Ecology Laboratory,

was then an undergraduate at tiny St. John’s College, an institution

famous for its great books-centered curriculum.

The power of Darwin’s work awoke Ellison’s interest in scientific

study, a shift in focus from the humanities that his fellow St. John’s

student and future wife Pippi ’75 (who went on to become a clinical

psychologist) was going through as well. Not long after, the Ellisons

transferred to UVM for the broader options of a university. Married

at age 21, highly focused on their scientific disciplines, and living

in a downtown Burlington apartment above Sheila’s Uniform Shop,

the undergraduate Ellisons inhabited a world more akin to grad students.

They built collegial relationships with faculty, earned their departments’

top student awards, and graduated Phi Beta Kappa.

Ellison

reflected on his undergraduate days when he returned to his alma mater

last semester as part of the President’s Distinguished Lecture

Series, delivering a talk on “Evolutionary Ecology and Human Reproduction.”

He drew a full house to Old Mill’s Dewey Lounge for a wide-ranging

talk that centered on his research, much of which is based on his lab’s

innovative use of a non-invasive, field-friendly way to monitor steroid

hormones through saliva samples. Spitting into test tubes has become

such familiar business to women of the Congo’s Ituri tribe that

they have coined one of Swahili’s newer compound words — kazimate

(spitwork).

The integration of perspectives across disciplines has been a key part

of Ellison’s career, the work of his lab, and his 2001 book, On

Fertile Ground: A Natural History of Human Reproduction. One reviewer

wrote of the publication, “Peter Ellison has now turned a fearsome

set of data-rich puzzles into a single elegant story.”

The same could be said for the professor’s talk at UVM, where his

skill in front of a class was on display in a wide-ranging presentation

examining the evolution of reproductive biology and human health issues

across cultures from Nepal to Poland to Africa to Boston. His research

has looked beyond the biology of reproduction to consider how such factors

as diet, disease, and labor relate to fertility. And his laboratory’s

studies of Western societies have explored everything from the issue

of women who postpone childbirth into their late 30s to the testosterone

levels of athletes and sports fans before and after competition. (In

the midst of Super Bowl frenzy, Ellison once facetiously quipped in

a National Public Radio interview that fans of a losing team “may

have a hard time growing a beard the next morning.”)

Distilling his UVM lecture into a “take-home message,” Ellison

referenced the epidemic of obesity in the Western world where sedentary

lifestyles have skewed the balance of food intake and activity, “pushing

human biology into an area that is really very extreme.” He closed

with a thought that was equal parts reminder and warning. “The

biology we’re endowed with is the product of evolutionary history.

Procuring food, doing work, forging families — they have sculpted

our physiology. Increasingly, we live in a world very far removed from

the environments that have shaped us.”

—Thomas Weaver