FEATURES DEPARTMENTS |

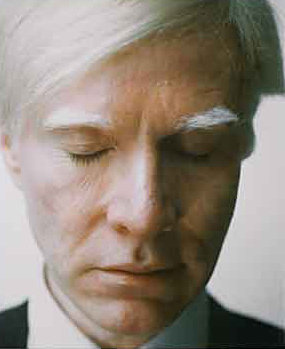

| Andy

Warhol, Untitled (Self-portrait) 1978 |

Andy Warhol:

Work and Play

Fleming show plumbs art, artist, and era

by Tom Weaver

Wigs for sale in the Fleming Museum gift shop suggest something a bit

different is going on at the university this semester. “Artist

Wig,” the package reads. “Color: platinum. Flame retardant.

One size fits all.” Ubiquitous as Andy Warhol’s work and persona

often seem, it would somehow be fitting if students cleared the stock,

and silver mop-tops started appearing across campus — bowed over

a book at Bailey/Howe, slouched on a couch at Billings, hustling across

the Green to make an 8 o’clock…

Bear with the Warhol dream sequence — how Pop! — it’s

just a small reach for a metaphor to illustrate the many ways that “Andy

Warhol: Work and Play,” the Fleming Museum show which runs through

June 8, has made its presence known during the spring 2003 semester.

Students have had the opportunity to talk about trailblazing 20th century

art in class, then walk across campus and see it on the wall as the

artist intended. Through art/drama camps, local kids have tried their

hands at the Warhol magic for making art from pop culture; adults got

their chance to be like Andy at a screenprinting workshop led by artist

Bill Davison, longtime UVM art professor. A series of events have explored

Warhol and his times through lectures, poetry, film, and music, featuring

visits from Warhol contemporaries and scholars.

The Fleming even landed Lou Reed, co-founder of the Velvet Underground,

for a concert at Ira Allen Chapel. Reed doesn’t play many dates

these days, but agreed to perform “a special little show”

because of the connection with Warhol, who was a friend and major artistic

influence on the Velvets. Drawing on recent songs or reaching back for

a crowd-pleasing “Walk on the Wild Side,” Reed delivered on

his promise for the audience packed in the chapel pews.

A

Call Wisely Taken

As she considers the many who deserve credit for bringing the Warhol

show to the Fleming, Janie Cohen, the museum’s director, ranks

serendipity high on the list. She traces the roots of “Work and

Play” to an afternoon several years ago when she was forwarded

a call from photographer and poet Gerard Malanga, who was Warhol’s

studio assistant during the wildly creative and productive years of

the 1960s.

Malanga was in search of LuAnn Rolley, an old friend who works at UVM,

to let her know about the death of a mutual friend. Through a mystical

chain of forwarded calls, he found his way to Cohen, who recognized

the name and gladly took the call. That began a conversation between

artist and curator about getting Malanga’s photos on display in

Vermont. And, by the way, Cohen put Malanga in touch with Rolley.

“Work and Play” began to truly take shape when Cohen learned

that Class of 1978 alumnus Jon Kilik, a prominent film producer, had

begun to collect art. Kilik is well-known for his work with Spike Lee,

in particular, but over the past decade has also worked with a number

of other film directors, notably Julian Schnabel, who were focused on

artists as their subject matter. Working with Schnabel on 1996’s

“Basquiat,” the story of Jean-Michel Basquiat, an artist befriended

(some say used) by Warhol, drew Kilik into the lives and work of artists.

Kilik says that as his knowledge of art grew, so did his interest in

collecting. He was naturally drawn to Warhol’s work because of

its relevance to his own life as a child of the sixties and seventies.

Kilik’s Warhol collection numbered eleven works when he first offered

it to Cohen for a Fleming show, but quickly doubled into a diverse collection

that forms the heart of the exhibit. Kilik’s loan to the museum

coincides with his 25th alumni Reunion, to be celebrated this spring,

when the show will be still on display.

When Cohen happened upon several rare Warhol works in the exotic locale

of downtown Burlington, it was as good as confirmation that the fates

meant for UVM to undertake a Warhol show. Browsing North Country Books,

a Church Street used bookstore owned by Mark Ciufo ’92, Cohen says

she did a “triple take” when she glanced in a glass case and

saw what looked to be very early Warhol drawings and prints — which

included a rare example of his “blotted line technique,” the

first unique style that he developed as a commercial artist.

The pieces, created by Warhol during his student years at the Carnegie

Institute of Technology in Pittsburgh, had been kept for years by Stuart

Williams, a college classmate of Warhol’s who lived in Winooski.

Preparing to move away from Vermont, Williams decided to lighten his

personal library and contacted Ciufo.

Tending his shop one evening in early March, Ciufo says he never set

out to be an art collector, but Williams’s mention that his collection

included “some cards” by Andy Warhol definitely caught his

attention. “I knew they were special,” Ciufo says, “but

I was taken aback because they weren’t what I expected.”

Indeed, amidst the electric chairs, soup cans, and celebrity portraits,

the whimsical drawings of a dancing figure on a Christmas card, which

is one of the first items visitors see when viewing “Work and Play,”

is among the exhibit’s least expected and most intriguing works.

Creating

Context

Building from the cornerstones of Kilik’s broad collection, Malanga’s

photographic documentation of the artist and his milieu, and North Country’s

rare early glimpse — Cohen strove to create a retrospective exhibit

and programming that would show not only Warhol’s work, but the

creative environment and cultural context that spawned it.

Serendipity may have provided the opportunity for the show, but bringing

it to reality required essential support that came from many places

— among them, financial backing from donors such as S.T. Griswold

& Company, and alumnus Stephen Kelly ’85; and pro bono work

on promotional materials and the catalogue from Jager Di Paola Kemp

Design and Christensen Design.

As Cohen looked to open the exhibit’s programming, she turned to

Malanga whose “studio assistant” title barely covers the essential

role he played for Warhol in the fertile creative years of the mid-sixties.

Malanga was the guy on his hands and knees pulling the squeegee over

the large flower paintings or Elvis Presley portraits or the Death and

Disaster series. He was behind the camera for the Screen Tests, a project

he collaborated on with Warhol, or in front of it performing his famous

whip dance.

Cohen placed the call this time, inviting Malanga to visit UVM for a

poetry reading and talk. And on February 9, the Fleming Auditorium is

at capacity for Malanga’s appearance. Waiting for the reading to

begin, I scan the crowd, playing a game of find the poet, expecting

someone who looks a little worn from the famous decadence of the era,

or at least a man in a black turtleneck. It is a pleasant surprise when

Malanga takes the stage. He’s aged well, wears a subdued flannel

shirt, and as he reads his recent poetry, it’s clear that his creative

vitality is going strong.

Malanga’s presence is inescapable in the Fleming exhibit —

his photo portraits, his poetry, or his role in silkscreening some of

Warhol’s most famous works. “Silkscreening in the sixties

was less precise — more like a roll of the dice,” Malanga

says. “Andy embraced the mistakes. He never rejected a painting;

the mistakes were a part of the art.”

Visual

Aids

At the Malanga reception, opening night, or through the exhibit’s

run, there’s been strong student attendance at the Warhol show.

Though the battles over Andy Warhol’s place in art history have

long since been fought, Art Professor Margo Thompson says she has found

a number of students who have a tough time embracing Warhol’s work.

“There’s a strong contingent of them who really value good

painting, such as the Impressionists, and they look at Warhol and react

by saying, ‘This is just not art.’ They don’t see that

it is any different from the world they live in.”

Thompson has a good laugh at the suggestion that such students are teetering

on one of those, as the cliché goes, “teachable moments.”Actually,

they are.

“Context, context, context,” Thompson says. “I try to

emphasize to students the seriousness of the artist’s intent. There

is a philosophy behind it; you can relate it to the world in a particular

way. The artists are not just running a game or putting you on. It is

genuine.”

That may be tough for some students or any Warhol skeptic to accept,

in part because of the artist’s own irreverence and reticence about

discussing his art. Put yourself in the uncomfortables shoes of this

interviewer for a 1962 piece in Art Voices:

Question: What is Pop Art trying to say?

Warhol: I don’t know.

Question: What do your rows of Campell soup cans signify?

Warhol: They’re things I had when I was a child.

Question: What does Coca Cola mean to you?

Warhol: Pop.

Professor

Reva Wolf, an art historian from SUNY-New Paltz, explores this Warhol

interview style extensively in an essay that is part of the “Work

and Play” catalogue published by the Fleming. Wolf’s key point

is the notion that Warhol, whether posing the questions or dancing around

the answers, essentially turned an interview into another art form.

It may be that Warhol’s evasion is inspired, in part, by a hope

that viewers will come to his work without pre-conceptions. That would

be a good thing. As Thompson says of her students, “I was very

pleased to hear some of them say that they were able to set aside their

own feelings and take the Warhol exhibit at face value.”

Those who do the same and take their own tours of the Fleming galleries

will be rewarded with a thought-provoking walk through American culture

both epochal and ephemeral, Birmingham race riots to drag queens.

“Warhol was such an American artist and really had his finger on

the pulse of popular culture,” Cohen says. “He understood

this country so well and helped us all to understand it better at a

very crucial time in our history.”

For more on the Fleming Museum’s Andy Warhol exhibit, see http://www.WarholAtTheFleming.org/index.html

or call (802) 656-0750. Thanks to Janie Cohen for providing text on

the images used in this article.