THE PROSPER VALLEY VIGNETTES:

At Home in the Valley Too - Prosper Valley Wildlife

The mid morning sun's white light shone through the sparse foliage and dappled the open page of my field notebook. I was in Barnard Gulf looking for a rumored beaver meadow. As I waded through knee-high sensitive and royal fern, I barely noticed the large black object clambering—quickly but not gracefully—up the hill ahead of me. I suppose the bear had been going about her day in this forest opening when I came onto the scene, had noticed me, and had chosen her moment of exit—all before I even knew she was there. Feeling humbled by this large wild animal's proximity, I walked to where she had stood and tried to locate her tracks. I first saw her big footprint next to a raspberry bush on the outskirts of the wetland. The berries had clearly been the object of her attention.

There is something quite different about following animal tracks that have just been created, compared to finding them days or weeks later; my imagination soared as I pictured her day to day life in these woods. Where had she been? Where was she going? Did she have a young one around? Was she a he? I lost her trail when she left the mud for higher ground, but her presence heightened my senses. I began to notice bear sign wherever I went in the Prosper Valley. I found territorial rubs, claw marks on American beech trees, and piles of bear scat filled with berry seeds. That summer, I never again saw a bear but I did strangely feel one's presence whenever I found myself walking through berry thickets.

As I traipsed all over the Valley in the months following my black bear sighting, I began to realize just how well-suited the Prosper Valley is for black bears. It was as if all the layers of the landscape—bedrock and surficial geology, soil and vegetation, and, in some cases, people—had conspired to provide the perfect black bear habitat. Geologic forces have sculpted both the lowlands and highlands that black bears rely on to provide a continuous supply of foods throughout the year. The low, wet areas are the first to have green, herbaceous forage in the spring when the bears emerge, ravenous, from their winter sleep. Then, come summer, when the forest's berries ripen, the bears move all over the woods to take advantage of patches of these high calorie fruits. With the onset of fall, and as the carbohydrate- and fat-rich beechnuts and acorns mature, they migrate to the higher, drier areas that support the trees producing these nuts. In these ways the physical and natural landscapes have collaborated to furnish black bear with ideal habitat. This same figurative collaboration occurs for every wild animal living on earth.

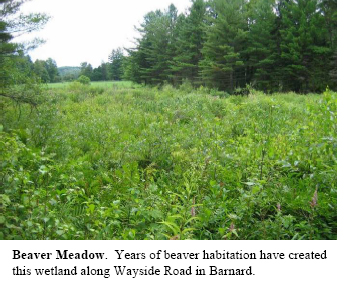

Though it is true that physical and biotic landscapes influence wildlife by defining the available habitat, it is also true that animals influence the landscapes surrounding them. Need I describe the ways that beaver alter their landscape? There is a place on Wayside Road in Barnard that has had beaver occupants for at least the past thirty years. Folks from the Barnard Town Garage have broken the beaver dam there half a dozen times within the last two years because it causes road flooding. But, the beavers don't give up. It's physiological—the sound of running water makes them build. And, for good reason—dam building benefits beaver in numerous ways; it makes the water high enough that they have a safe haven beneath winter ice, maintains wetland ecosystems which support their favored plant food species, and also expands what's accessible to them—flooding makes more trees within striking distance of the safety of water. Beavers are the only animal, besides humans, known to actually create their own habitat.

Though the beaver is quite skilled at creating its own habitat, it isn't so adept at sustaining it. Because beavers eat the inner bark of hardwoods but ignore conifers, the forest surrounding the Wayside Road wetland is mainly conifer. In essence, beaver have changed a hardwood forest into white pine woodland and wet meadow, and in so doing, eliminated their immediate food supply. Beavers compensate for their unsustainable resource consumption by practicing field rotation—cycling through several different locations to allow recently depleted trees to regenerate.

After a summer of close observation, I feel akin to the animals that live in the Prosper Valley. In the same way that the physical and natural landscapes bestow sufficient habitat upon the black bear, beaver and countless other wildlife species, they provide a superb habitat for those people the Valley sustains. They determine the types of lives to be led here and the ways in which people interact with the land. Though humans are influenced by the landscape, they also directly influence it; similar to the beaver, we shape the land to fulfill our own needs. For this reason, I regard the beaver's tendency to use up its habitat as a caution relevant to my own species. Can humans learn from the beaver's oversights before we find ourselves in a metaphorical conifer wasteland with nothing to eat?