THE PROSPER VALLEY VIGNETTES:

Familiar Hills and Hollows - Prosper Valley Topography and Hydrology

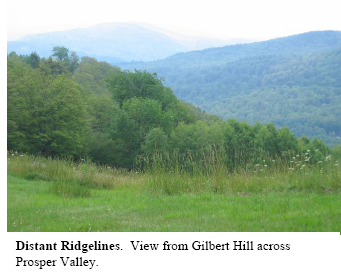

It was a hazy, midsummer day when I first stood in the field that stretches along the spine of Gilbert Hill. Beside me was a stonewall that marks the town line between Pomfret to the northeast and Woodstock to the southwest. But, this was one time when I wasn't thinking about stonewalls—the breathtaking views from the ridgeline had entirely commandeered my thoughts. Looking across the Prosper Valley, I could glimpse, through the haze, the surrounding hills and distant ridgelines. Below, I could make out the Gulf Brook—actually the trees lining its banks—snaking through hayfields and front yards. I took a seat on one of the wooden benches in this rectangular field and began thinking about the landscape shapes that had become familiar and cherished over the summer: the narrow valley, the rounded hilltops, and the steep hillsides, becoming gentler on the approach into Woodstock. How had these landforms come to be? Could Gulf Brook, a small stream, have shaped these impressive landforms?

Geologists claim that the Valley's landforms are the result of a long partnership between rock and water. Much has changed since the time hundreds of millions of years ago when the young Green Mountain sediments that had eroded into the Iapetus Ocean were uplifted to become the bedrock now underlying the Prosper Valley. Apparently, pressures from long-ago continental collisions caused the bedrock to crack, thus determining the course of most of the streams in the Prosper Valley. Because fractures exposed an increased surface area to the weathering agents of water, air and acids, materials near the cracks were more quickly dislodged and removed by ice and water. It is similar to a birthday cake that's cut before glazing—as you pour the glaze, little bits of cake from the cut edges float away. Over time, weathering of weakened bedrock zones established stream channels. Major topographical features, like the Green Mountain belt and its foothills, come from large-scale geological events, but smaller-scale hills and valleys, like Mount Tom and the Barnard Gulf, probably originated by this kind of gradual weathering of weak zones of bedrock. The numerous streams draining into the Gulf Brook have carved valleys that are oriented roughly eastwest. This pattern on our present-day landscape reflects the orientation of bedrockcracking associated with continental collisions that occurred hundreds of millions of years ago.

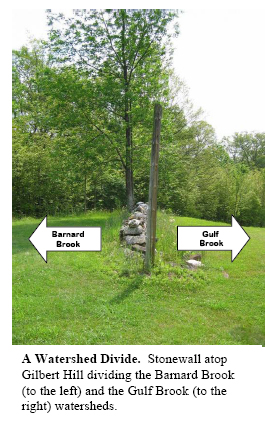

Geological and hydrological processes have interacted to sculpt the topography of the Prosper Valley, to establish where we see hills and where we see valleys. Simultaneously, the topography has directed the water's path. From the farthest highlands drained by the Gulf Brook's small tributaries to the low farm fields lining the widened Gulf Brook, water connects every square inch of land in the Prosper Valley. Any rain or snow that falls just inside the highest surrounding ridgelines—if not evaporated or usurped by plant roots—will make its way to the Gulf Brook, then the Ottauquechee and Connecticut Rivers, and eventually the Atlantic Ocean. The Prosper Valley is, therefore, a watershed, an area of land that drains into a common body of water. In this case, that common body of water is the Gulf Brook. The longsince forgotten stonewall that I discovered marking the boundary between Pomfret and

Woodstock on Gilbert Hill also marks the boundary between the Barnard and Gulf Brook watersheds. Water that falls on the northeast side of the stones eventually flows into the South Pomfret valley and the Barnard Brook while water that falls on the southwest side of the stones contributes to the Gulf Brook. While town boundaries are often arbitrary lines drawn on a map, watershed boundaries are ecologically meaningful bounds of interacting ecosystems; they govern the flow of nutrients, sediments, pollutants, and aquatic life. Because all of these systems are connected, a change in any of them can have profound effects on countless plants, animals, and humans throughout the watershed and beyond. For this reason, members of a watershed community— whether they be plant, animal, or human—share a common experience, now and in the future.

The shapes that geologic and hydrologic forces have afforded the Prosper Valley have also affected people. The bedrock-defined waterways were primary travel-routes for European settlers venturing northward from Connecticut and Massachusetts into the Valley. And, before the ease of modern transportation, the hollows and valleys defined people's communities. Today, this topography bestows the very landforms to which we humans connect and from which we derive a sense of place and belonging. And, in this way, ancient cracks in rocks have created community.